Nipah virus

| Nipah virus | |

|---|---|

| |

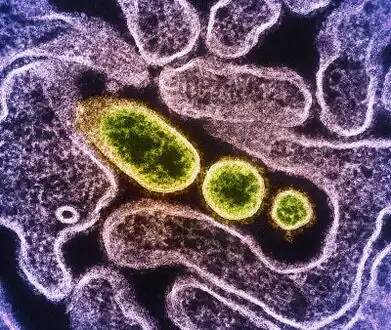

| False-color electron micrograph showing a Nipah virus particle (purple) by an infected Vero cell (brown) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Henipavirus |

| Species: | Nipah virus |

Nipah virus is a bat-borne virus that causes Nipah virus infection in humans and other animals.[1]

The disease with a high mortality rate. Numerous disease outbreaks caused by Nipah virus have occurred in South and Southeast Asia. Nipah virus belongs to the genus Henipavirus along with the Hendra virus, which has also caused disease outbreaks.[2]

It was reported on September 14, 2023, that five cases, including two deaths, were confirmed in Kozhikode district in Kerala, India. With some 700 people linked to the two deaths[3][4]

Virology

Like other henipaviruses, the Nipah virus genome is a single (nonsegmented) negative-sense, single-stranded RNA of over 18 kb, which is substantially longer than that of other paramyxoviruses.[5][6] The enveloped virus particles are variable in shape, and can be filamentous or spherical; they contain a helical nucleocapsid.[5] Six structural proteins are generated: N (nucleocapsid), P (phosphoprotein), M (matrix), F (fusion), G (glycoprotein) and L (RNA polymerase). The P open reading frame also encodes three nonstructural proteins, C, V and W.[7][8]

There are two envelope glycoproteins. The G glycoprotein ectodomain assembles as a homotetramer to form the viral anti-receptor or attachment protein, which binds to the receptor on the host cell. Each strand in the ectodomain consists of four distinct regions: at the N-terminal and connecting to the viral surface is the helical stalk, followed by the beta-sandwich neck domain, the linker region and finally, at the C-terminal, four heads which contain host cell receptor binding domains.[9] Each head consists of a beta-propellor structure with six blades. There are three unique folding patterns of the heads, resulting in a 2-up/2-down configuration where two heads are positioned distal to the virus and two heads are proximal. Due to the folding patterns and subsequent arrangement of the heads, only one of the four heads is positioned with its binding site accessible to associate with the host B2/B3 receptor.[9] The G protein head domain is also highly antigenic, inducing head-specific antibodies in primate models. As such, it is a prime target for vaccine development as well as antibody therapy. One head-specific antibody, m102.4, has been used in compassionate use cases and has completed Phase 1 clinical trials.[10] The F glycoprotein forms a trimer, which mediates membrane fusion.[5][6]

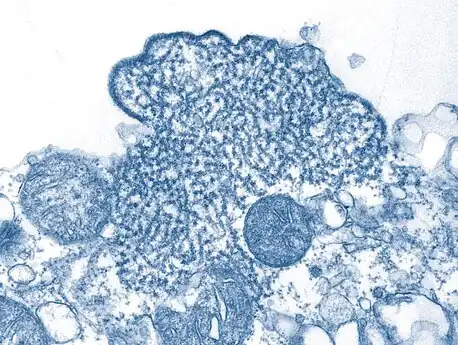

Transmission electron micrograph of mature extracellular Nipah Virus particles (yellow) near the periphery of an infected VERO cell

Transmission electron micrograph of mature extracellular Nipah Virus particles (yellow) near the periphery of an infected VERO cell.jpg.webp) Nipah virus particles

Nipah virus particles Transmission electron micrograph depicted a number of Nipah virus virions

Transmission electron micrograph depicted a number of Nipah virus virions

Tropism

Ephrins B2 and B3 have been identified as the main receptors for Nipah virus.[5][6][11] Ephrin subtypes have a complex distribution of expression throughout the body, where the B3 is noted to have particularly high expression in some forebrain subregions.[12]

Mechanism

In terms of the mechanism of this infection we find that entry is via the oro-nasal route. The site of initial replication has not been determined (however lymphoid and respiratory tissues could be probable sites), secondary replication occurs in the endothelium. We later find that the glycoprotein G of NiV binds to the cellular receptor Ephrin-B2.[13]

The CNS is overtaken via the haematogenous route. The virus is highly lethal due to its ability to elude the human immune defence; the P gene inhibit interferon activity, interferons are signaling proteins released in response to the presence of a virus[14][13]

Transmission

Based on seroprevalence data and virus isolations, the primary reservoir for Nipah virus was identified as Pteropid fruit bats, including Pteropus vampyrus (large flying fox), and Pteropus hypomelanus (small flying fox), both found in Malaysia.[15]

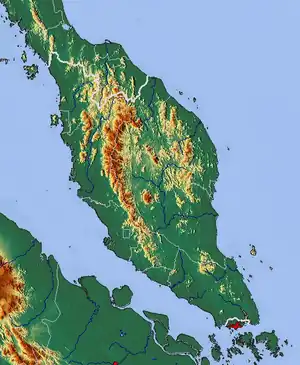

The transmission of Nipah virus from flying foxes to pigs is thought to be due to an increasing overlap between bat habitats and piggeries in peninsular Malaysia. At the index farm, fruit orchards were in close proximity to the piggery, allowing the spillage of urine, faeces and partially eaten fruit onto the pigs.[16]

Retrospective studies demonstrate that viral spillover into pigs may have been occurring, undetected, in Malaysia since 1996.[17]

During 1998, viral spread was aided by the transfer of infected pigs to other farms, where new outbreaks occurred.[18]

The risk of exposure is high for hospital workers and caretakers of those infected with the virus. In Malaysia and Singapore, Nipah virus infection occurred in those with close contact to infected pigs. In Bangladesh and India, the disease has been linked to consumption of raw date palm sap (toddy) and eating of fruits partially consumed by bats and using water from wells inhabited by bats.[19][20][21]

Geographic distribution

Nipah virus has been isolated from Lyle's flying fox (Pteropus lylei) in Cambodia[22] and viral RNA found in urine and saliva from P. lylei and Horsfield's roundleaf bat (Hipposideros larvatus) in Thailand.[23]

Infective virus has also been isolated from environmental samples of bat urine and partially eaten fruit in Malaysia.[24]

Antibodies to henipaviruses have also been found in fruit bats in Madagascar (Pteropus rufus, Eidolon dupreanum)[25] and Ghana (Eidolon helvum)[26]indicating a wide geographic distribution of the viruses.

No infection of humans or other species have been observed in Cambodia, Thailand or Africa as of 2018.[27]

Disease

Presentation

Symptoms of infection from an outbreak in Malaysia were primarily encephalitic in humans .[28] Other outbreaks have caused respiratory illness in humans, increasing the likelihood of human-to-human transmission and indicating the existence of more dangerous strains of the virus.[7][29]

These symptoms can be followed by more serious conditions including:[32]

- Drowsiness

- Altered consciousness

- Acute encephalitis

- Atypical pneumonia

- Severe respiratory distress

- Seizures

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of Nipah virus infection is made by:ARN detection can be done using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from throat swabs, cerebrospinal fluid, urine and blood analysis during acute and convalescent stages of the disease.[33] IgG and IgM antibody detection can be done after recovery to confirm Nipah virus infection. Immunohistochemistry on tissues collected during autopsy also confirms the disease.[33]

Treatment

Currently there is no specific treatment for Nipah virus infection as of 2020.[34] The mainstay of treatment is supportive care.[35][34] Standard infection control practices and proper barrier nursing techniques are recommended to avoid the spread of the infection from person to person,[35] all suspected cases of Nipah virus infection should be isolated.[36] While tentative evidence supports the use of ribavirin, it has not yet been studied in people with the disease.[35]

Epidemiology

Outbreaks

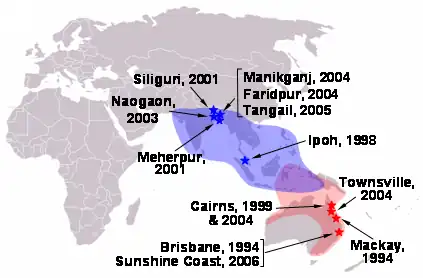

Nipah virus infection outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh and India. The highest mortality due to Nipah virus infection has occurred in Bangladesh, where outbreaks are typically seen in winter.[37] Nipah virus first appeared in 1998, in peninsular Malaysia in pigs and pig farmers. By mid-1999, more than 265 human cases of encephalitis, including 105 deaths, had been reported in Malaysia, and 11 cases of either encephalitis or respiratory illness with one fatality were reported in Singapore.[38] In 2001, Nipah virus was reported from Meherpur District, Bangladesh[39][40] and Siliguri, India.[39] The outbreak again appeared in 2003, 2004 and 2005 in Naogaon District, Manikganj District, Rajbari District, Faridpur District and Tangail District.[40] In Bangladesh there were also outbreaks in subsequent years.[41] In September 2021, Nipah virus resurfaced in Kerala, India claiming the life of a 12-year-old boy.[42]

In 2023 we have seen several outbreaks. On 4 January 2023 , 11 cases (10 confirmed and one probable) including eight deaths (Case Fatality Rate (CFR) 73%) have been reported in Bangladesh. WHO assesed the risk as high at the national level.[43] Then in September we saw India have as of 14 September 2023, five cases, including two deaths, being confirmed in Kozhikode district in Kerala. The government has prepared a contact list of over 700 people linked to the two deaths, of whom two family members and a healthcare worker tested positive for the virus.[3][44]

Locations of henipavirus outbreaks (red stars–Hendra virus; blue stars–Nipah virus) and distribution of henipavirus flying fox reservoirs (red shading–Hendra virus; blue shading–Nipah virus)

Locations of henipavirus outbreaks (red stars–Hendra virus; blue stars–Nipah virus) and distribution of henipavirus flying fox reservoirs (red shading–Hendra virus; blue shading–Nipah virus)

History

The first cases of Nipah virus infection were identified in 1998, when an outbreak of neurological and respiratory disease on pig farms in peninsular Malaysia caused 265 human cases, with 108 deaths.[4][17][45][46] The virus itself was isolated the following year in 1999.[33] This outbreak resulted in the culling of one million pigs. In Singapore, 11 cases, including one death, occurred in abattoir workers exposed to pigs imported from the affected Malaysian farms. The Nipah virus has been classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a Category C agent.[47]

The name "Nipah" refers to the place, Sungai Nipah (literally 'nipah river') in Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan, the source of the human case from which Nipah virus was first isolated.[48][49] Nipah virus is one of several viruses identified by WHO as a likely cause of a future epidemic in a new plan developed after the Ebola epidemic for urgent research and development before and during an epidemic toward new diagnostic tests, vaccines and medicines.[50][51]

The outbreak was originally mistaken for Japanese encephalitis, but physicians in the area noted that persons who had been vaccinated against Japanese encephalitis were not protected in the epidemic, and the number of cases among adults was unusual.[52] Although these observations were recorded in the first month of the outbreak, the Ministry of Health failed to take them into account, and launched a nationwide campaign to educate people on the dangers of Japanese encephalitis.[53][54]

Evolution

The most likely origin of the Nipah virus was in 1947 (95% credible interval: 1888–1988).[55]

There are two clades of this virus—one with its origin in 1995 (95% credible interval: 1985–2002) and a second with its origin in 1985 (95% credible interval: 1971–1996). The mutation rate was estimated to be 6.5 × 10−4 substitution/site/year (95% credible interval: 2.3 × 10−4 –1.18 × 10−3).[56][57]

See also

References

- ↑ Barlow, Gavin; Irving, William L.; Moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ↑ Singh, Raj Kumar; Dhama, Kuldeep; Chakraborty, Sandip; Tiwari, Ruchi; Natesan, Senthilkumar; Khandia, Rekha; Munjal, Ashok; Vora, Kranti Suresh; Latheef, Shyma K.; Karthik, Kumaragurubaran; Singh Malik, Yashpal; Singh, Rajendra; Chaicumpa, Wanpen; Mourya, Devendra T. (December 2019). "Nipah virus: epidemiology, pathology, immunobiology and advances in diagnosis, vaccine designing and control strategies - a comprehensive review". The Veterinary Quarterly. 39 (1): 26–55. doi:10.1080/01652176.2019.1580827. ISSN 1875-5941. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- 1 2 Bureau, The Hindu (13 September 2023). "Nipah outbreak | Number of cases rises to 5 in Kerala; 789 contacts kept under watch". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- 1 2 Conroy, Gemma (20 September 2023). "Nipah virus outbreak: what scientists know so far". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02967-x. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Aditi, M. Shariff (2019). "Nipah virus infection: A review". Epidemiology and Infection. 147: E95. doi:10.1017/S0950268819000086. PMC 6518547. PMID 30869046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 Moushimi Amaya, Christopher C. Broder (2020). "Vaccines to emerging viruses: Nipah and Hendra". Annual Review of Virology. 7 (1): 447–473. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-021920-113833. PMC 8782152. PMID 32991264. S2CID 222158412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 Rathish, Balram; Vaishnani, Kushal (2023). "Nipah Virus". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Sun, B; Jia, L; Liang, B; Chen, Q; Liu, D (October 2018). "Phylogeography, Transmission, and Viral Proteins of Nipah Virus". Virologica Sinica. 33 (5): 385–393. doi:10.1007/s12250-018-0050-1. PMID 30311101. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- 1 2 Wang, Zhaoqian; Amaya, Moushimi; Addetia, Amin; Dang, Ha V.; Reggiano, Gabriella; Yan, Lianying; Hickey, Andrew C.; DiMaio, Frank; Broder, Christopher C.; Veesler, David (2022-03-25). "Architecture and antigenicity of the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein". Science. 375 (6587): 1373–1378. Bibcode:2022Sci...375.1373W. doi:10.1126/science.abm5561. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35239409. S2CID 246751048. Archived from the original on 2023-03-01. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ↑ Johnson, Kendra; Vu, Michelle; Freiberg, Alexander N (2021-09-29). "Recent advances in combating Nipah virus". Faculty Reviews. 10: 74. doi:10.12703/r/10-74. ISSN 2732-432X. PMC 8483238. PMID 34632460.

- ↑ Lee B, Ataman ZA; Ataman (2011). "Modes of paramyxovirus fusion: a Henipavirus perspective". Trends in Microbiology. 19 (8): 389–399. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.005. PMC 3264399. PMID 21511478.

- ↑ Hruska, Martin; Dalva, Matthew B. (May 2012). "Ephrin regulation of synapse formation, function and plasticity". Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 50 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.004. ISSN 1044-7431. PMC 3631567. PMID 22449939.

- 1 2 Shariff, M. (22 February 2019). "Nipah virus infection: A review". Epidemiology and Infection. 147: e95. doi:10.1017/S0950268819000086. ISSN 0950-2688. PMC 6518547. PMID 30869046.

- ↑ De Andrea, Marco; Ravera, Raffaella; Gioia, Daniela; Gariglio, Marisa; Landolfo, Santo (May 2002). "The interferon system: an overview". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 6: A41–A46. doi:10.1053/ejpn.2002.0573. PMID 12365360. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ↑ Constable, Harriet (2021-01-12). "The other virus that worries Asia". www.bbc.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ↑ Chua KB, Chua BH, Wang CW (2002). "Anthropogenic deforestation, El Niño and the emergence of Nipah virus in Malaysia". The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. 24 (1): 15–21. PMID 16329551.

- 1 2 Field, H; Young, P; Yob, JM; Mills, J; Hall, L; MacKenzie, J (2001). "The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 307–14. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01384-3. PMID 11334748.

- ↑ Devnath, Popy; Wajed, Shah; Chandra Das, Ripu; Kar, Sanchita; Islam, Iftekharul; Masud, H. M. Abdullah Al (1 September 2022). "The pathogenesis of Nipah virus: A review". Microbial Pathogenesis. 170: 105693. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105693. ISSN 0882-4010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S.; Hossain, M. Jahangir (2012). Transmission of Human Infection with Nipah Virus. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Balan, Sarita (21 May 2018). "6 Nipah virus deaths in Kerala: Bat-infested house well of first victims sealed". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Transmission | Nipah Virus (NiV) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ↑ Reynes JM, Counor D, Ong S (2005). "Nipah virus in Lyle's flying foxes, Cambodia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1042–7. doi:10.3201/eid1107.041350. PMC 3371782. PMID 16022778.

- ↑ Wacharapluesadee S, Lumlertdacha B, Boongird K (2005). "Bat Nipah virus, Thailand". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1949–51. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050613. PMC 3367639. PMID 16485487.

- ↑ Chua KB, Koh CL, Hooi PS (2002). "Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes". Microbes and Infection. 4 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01522-2. PMID 11880045.

- ↑ Lehlé C, Razafitrimo G, Razainirina J (2007). "Henipavirus and Tioman virus antibodies in pteropodid bats, Madagascar". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 159–61. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060791. PMC 2725826. PMID 17370536.

- ↑ Hayman DT, et al. (2008). Montgomery JM (ed.). "Evidence of henipavirus infection in West African fruit bats". PLOS ONE. 3 (7): 2739. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2739H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002739. PMC 2453319. PMID 18648649.

- ↑ "Nipah virus infection". WHO. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ↑ Lam, Sai Kit; Chua, Kaw Bing (1 May 2002). "Nipah Virus Encephalitis Outbreak in Malaysia". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 34 (Supplement_2): S48–S51. doi:10.1086/338818. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Singhai, Monil; Jain, Ruchi; Jain, Sarika; Bala, Manju; Singh, Sujeet; Goyal, Rajeev. "Nipah Virus Disease: Recent Perspective and One Health Approach". Annals of Global Health. 87 (1): 102. doi:10.5334/aogh.3431. ISSN 2214-9996. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ↑ Ang, Brenda S. P.; Lim, Tchoyoson C. C.; Wang, Linfa (June 2018). "Nipah Virus Infection". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 56 (6): e01875–17. doi:10.1128/JCM.01875-17. ISSN 1098-660X. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ "Signs and Symptoms | Nipah Virus (NiV) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 6 October 2020. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ↑ "Nipah virus". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2021-08-23. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- 1 2 3 "Nipah Virus (NiV) CDC". www.cdc.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 Sharma, V; Kaushik, S; Kumar, R; Yadav, JP; Kaushik, S (January 2019). "Emerging trends of Nipah virus: A review". Reviews in Medical Virology. 29 (1): e2010. doi:10.1002/rmv.2010. PMC 7169151. PMID 30251294.

- 1 2 3 "Treatment | Nipah Virus (NiV) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Nipah yet to be confirmed, 86 under observation: Shailaja". OnManorama. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ↑ Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, et al. (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- ↑ Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang LF (January 2006). "Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 4 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1323. PMC 7097447. PMID 16357858. S2CID 24764543.

- 1 2 Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, et al. (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- 1 2 Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I, et al. (December 2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (12): 2082–7. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701. PMC 3323384. PMID 15663842.

- ↑ "Nipah virus outbreaks in the WHO South-East Asia Region". South-East Asia Regional Office. WHO. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "India's COVID-battered Kerala state now on alert for Nipah virus". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Nipah virus infection - Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ↑ Millson, Alex (14 September 2023). "What Is Nipah and Why Is the Deadly Virus Flaring Up Again". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (30 April 1999). "Update: outbreak of Nipah virus—Malaysia and Singapore, 1999". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 48 (16): 335–7. PMID 10366143. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ↑ Lai-Meng Looi; Kaw-Bing Chua (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. 29 (2): 63–67. PMID 19108397. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases. bt.cdc.gov

- ↑ Siva SR, Chong HT, Tan CT (2009). "Ten year clinical and serological outcomes of Nipah virus infection" (PDF). Neurology Asia. 14: 53–58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-22. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ↑ "Spillover – Zika, Ebola & Beyond". pbs.org. PBS. 3 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Kieny, Marie-Paule. "After Ebola, a Blueprint Emerges to Jump-Start R&D". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "LIST OF PATHOGENS". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Dobbs and the viral encephalitis outbreak". Archived from the original on 2021-09-07. Retrieved 2021-09-12.. Archived thread from the Malaysian Doctors Only BBS Archived 18 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Looi, Lai-Meng; Chua, Kaw-Bing (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. Department of Pathology, University of Malaya and National Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 29 (2): 63–67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Lim, C. C.; Sitoh, Y. Y.; Hui, F.; Lee, K. E.; Ang, B. S.; Lim, E.; Lim, W. E.; Oh, H. M.; Tambyah, P. A.; Wong, J. S.; Tan, C. B.; Chee, T. S. (March 2000). "Nipah viral encephalitis or Japanese encephalitis? MR findings in a new zoonotic disease". AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 21 (3): 455–461. ISSN 0195-6108. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ↑ Lo Presti A, Cella E, Giovanetti M, Lai A, Angeletti S, Zehender G, Ciccozzi M (2015). "Origin and evolution of Nipah virus". J Med Virol. 88 (3): 380–388. doi:10.1002/jmv.24345. PMID 26252523. S2CID 24428068.

- ↑ Hauser, N; Gushiken, AC; Narayanan, S; Kottilil, S; Chua, JV (14 February 2021). "Evolution of Nipah Virus Infection: Past, Present, and Future Considerations". Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 6 (1). doi:10.3390/tropicalmed6010024. PMID 33672796. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ↑ Li, K; Yan, S; Wang, N; He, W; Guan, H; He, C; Wang, Z; Lu, M; He, W; Ye, R; Veit, M; Su, S (January 2020). "Emergence and adaptive evolution of Nipah virus". Transboundary and emerging diseases. 67 (1): 121–132. doi:10.1111/tbed.13330. PMID 31408582. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

Further reading

- "Analytics". OIE World Animal Health Information Database. Archived from the original on 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- "Fighting Nipah virus". Research: Animals: Livestock. CSIRO. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- Enserink M (February 2009). "Virus's Achilles' Heel Revealed". Science Now. AAAS. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009.