Nitrovasodilator

| Nitrovasodilator | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Angina pectoris, vasodilation |

| ATC code | C01DA |

| Biological target | Guanylate cyclase |

| In Wikidata | |

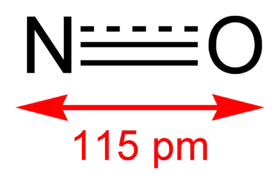

A nitrovasodilator is a pharmaceutical agent that causes vasodilation (widening of blood vessels) by donation of nitric oxide (NO),[1] and is mostly used for the treatment and prevention of angina pectoris.

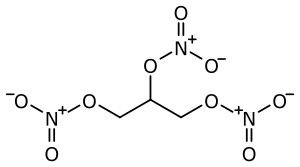

This group of drugs includes nitrates (esters of nitric acid), which are reduced to NO in the body, as well as some other substances.

Examples

Here is a list of examples of the nitrate type (in alphabetical order):[2]

- Diethylene glycol dinitrate

- Glyceryl trinitrate (nitroglycerin)

- Isosorbide mononitrate and dinitrate

- Itramin tosilate

- Nicorandil (which additionally acts as a potassium channel opener)

- Pentaerithrityl tetranitrate

- Propatylnitrate

- Sinitrodil

- Tenitramine

- Trolnitrate

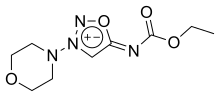

Nitrovasodilators which aren't nitrates include molsidomine and its active metabolite linsidomine, as well as sodium nitroprusside. These substances do not need to be reduced to donate NO.[2][3]

Medical uses

The nitrates are used for the treatment and prevention of angina and acute myocardial infarction, while molsidomine acts too slowly to be useful for the treatment of acute angina.[2] For quick action in the treatment of angina, glyceryl trinitrate is used in form of a sublingual spray (nitro spray) or as soft capsules to be crunched.[4]

Nitroprusside is used intravenously for the treatment of hypertensive crises, heart failure, and lowering of blood pressure during surgery.[5][6]

Contraindications

Nitrovasodilators are contraindicated under circumstances where lowering of blood pressure can be dangerous. This includes, with some variation between the individual substances, severe hypotension (low blood pressure), shock including cardiogenic shock, and anaemia. Whether a specific drug is useful or harmful under heart failure and myocardial infarction depends on its speed of action: Fast acting substances such as glyceryl trinitrate and nitroprusside can be helpful for controlling blood pressure and consequently the amount of blood the heart has to pump, if the application is monitored continuously. Slow acting substances would hold the danger of ischaemia due to an uncontrollably low blood pressure and are therefore contraindicated. Depending on the circumstances, even fast acting substances can be contraindicated – for example, glyceryl trinitrate in patients with obstructive heart failure.[2][4]

These drugs are also contraindicated in patients that have recently taken PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra).[4]

Adverse effects

Most side effects are direct consequences of the vasodilation and the following low blood pressure. They include headache ("nitrate headache") resulting from the widening of blood vessels in the brain, reflex tachycardia (fast heart rate), flush, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. These effects usually subside after a few days if the treatment is continued.[2]

Occasionally, severe hypotension occurs shortly after beginning of treatment, possibly resulting in intensified angina symptoms or syncope, sometimes with bradycardia (slow heart rate).[4]

Interactions

A number of drugs add to the low blood pressure caused by nitrovasodilators: for example, other vasodilators, antihypertensive drugs, tricyclic antidepressantss, antipsychotics, general anaesthetics, as well as ethanol. Combination with PDE5 inhibitors, including sildenafil (Viagra), is contraindicated because potentially life-threatening hypotension may occur.[2][4]

Nitrates increase the bioavailability of dihydroergotamine (DHE). High DHE levels may result in coronary spasms in patients with coronary disease.[4] This interaction is not described for non-nitrate nitrovasodilators.

Mechanism of action

Nitrovasodilators are prodrugs that donate NO by various mechanisms. Nitrates undergo chemical reduction, likely mediated by enzymes. Molsidomine and nitroprusside already contain nitrogen in the right oxidation state (+2) and liberate NO without the aid of enzymes.[3]

NO stimulates the soluble form of the enzyme guanylate cyclase in the smooth muscle cells of blood vessels. Guanylate cyclase produces cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) from guanosine triphosphate (GTP). cGMP in turn activates cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase G, which phosphorylates various proteins that play a role in decreasing intracellular calcium levels, leading to relaxation of the muscle cells and thus to dilation of blood vessels.[3][7]

The most important effect in angina is the widening of veins, which increases their capacity to hold blood ("venous pooling") and reduces the pressure of the blood returning to the heart (the preload). Widening of the large arteries also reduces the pressure against which the heart has to pump, the afterload. Lower preload and afterload result in the heart needing less energy and thus less oxygen. Besides, NO donated by nitrovasodilators can reduce coronary spasms, increasing the heart's oxygen supply.[2]

PDE5 inhibitors block deactivation of cGMP by the enzyme phosphodiesterase-5. In combination with the increased cGMP production caused by nitrovasodilators, this leads to high concentrations of cGMP, extensive venous pooling, and potentially life-threatening hypotension.[8][9]

Nitrate tolerance

Nitrates exhibit development of tolerance, or more specifically tachyphylaxis, meaning that repeated application results in a fast decrease of effect, usually within 24 hours. A pause of six to eight hours restores the original effectiveness. This phenomenon was originally thought to be a consequence of depletion of thiol (–SH) groups necessary for the reduction of nitrates. While this theory would fit the fact that molsidomine (which is not reduced) does not exhibit tachyphylaxis, it has meanwhile been refuted. Newer theories include increase of oxidative stress resulting in deactivation of NO to peroxynitrite, and liberation of the vasoconstrictors angiotensin II and endothelin as the blood vessels' reaction to NO-mediated vasodilation.[2] Other studies demonstrate a role of folates in preventing nitrate tolerance in arteries.[10]

Differences in pharmacokinetics

Nitrates mainly differ in speed and duration of their action. Glyceryl trinitrate acts fast and short (10 to 30 minutes), while most other nitrates have a slower onset of action, but are effective for up to six hours. Molsidomine, as has been mentioned, not only acts slowly but also differs from the nitrates in exhibiting no tolerance.[2] Nitroprusside, given intravenously, acts immediately, and after stopping the infusion blood pressure returns to its previous level within ten minutes.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Brandes RP, Kim D, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, et al. (January 2000). "Increased nitrovasodilator sensitivity in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice: role of soluble guanylyl cyclase". Hypertension. 35 (1 Pt 2): 231–6. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.231. PMID 10642303. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mutschler, Ernst; Schäfer-Korting, Monika (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 554–558. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- 1 2 3 Steinhilber, D; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M; Roth, HJ (2005). Medizinische Chemie (in German). Stuttgart: Deutscher Apotheker Verlag. pp. 257–61. ISBN 978-3-7692-3483-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haberfeld, H, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (2007/2008 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 5417–8, 5426–9, 5784–5. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ↑ Friederich, JA; Butterworth, JF 4th (July 1995). "Sodium Nitroprusside: Twenty Years and Counting". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 81 (1): 152–162. doi:10.1213/00000539-199507000-00031. PMID 7598246.

- 1 2 Sodium nitroprusside: Monograph.

- ↑ Tanaka, Y.; Tang, G.; Takizawa, K.; Otsuka, K.; Eghbali, M.; Song, M.; Nishimaru, K.; Shigenobu, K.; Koike, K.; Stefani, E.; Toro, L. (2005). "Kv Channels Contribute to Nitric Oxide- and Atrial Natriuretic Peptide-Induced Relaxation of a Rat Conduit Artery". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 317 (1): 341–354. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096115. PMID 16394199.

- ↑ Webb, D. J.; Freestone, S.; Allen, M. J.; Muirhead, G. J. (1999). "Sildenafil citrate and blood-pressure-lowering drugs: Results of drug interaction studies with an organic nitrate and a calcium antagonist". The American Journal of Cardiology. 83 (5A): 21C–28C. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00044-2. PMID 10078539.

- ↑ Cheitlin, M. D.; Hutter Jr, A. M.; Brindis, R. G.; Ganz, P.; Kaul, S.; Russell Jr, R. O.; Zusman, R. M.; Forrester, J. S.; Douglas, P. S.; Faxon, D. P.; Fisher, J. D.; Gibbons, R. J.; Halperin, J. L.; Hutter, A. M.; Hochman, J. S.; Kaul, S.; Weintraub, W. S.; Winters, W. L.; Wolk, M. J. (1999). "ACC/AHA expert consensus document. Use of sildenafil (Viagra) in patients with cardiovascular disease. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 33 (1): 273–282. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00656-1. PMID 9935041.

- ↑ http://medreviews.com/sites/default/files/2016-11/RICM_31_62_0.pdf