Paradoxical embolism

| Paradoxical embolism | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Crossed embolism | |

| |

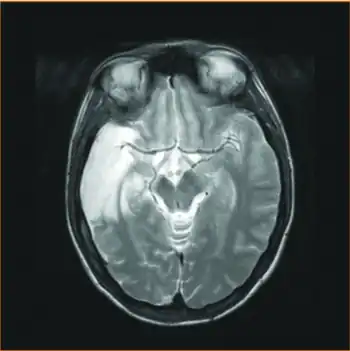

| MRI sequence - injury was sustained before PFO closure, most probably due to paradoxical embolism after documented deep venous thrombosis | |

An embolus, is described as a free-floating mass, located inside blood vessels that can travel from one site in the blood stream to another. An embolus can be made up of solid (like a blood clot), liquid (like amniotic fluid), or gas (like air). Once these masses get "stuck" in a different blood vessel, it is then known as an "embolism." An embolism can cause ischemia - or damage to an organ from lack of oxygen.[1] A paradoxical embolism is a specific type of embolism in which the emboli travels from the right side of the heart or "venous circulation," travels to the left side of the heart or "arterial circulation," and lodges itself in a blood vessel known as an artery.[2] Thus, it is termed "paradoxical" because the emboli lands in an artery, rather than a vein.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms experienced by an individual with a paradoxical embolism can be from both the original site of thrombus and the location of where the emboli lodges. It is believed that the most common origin site of thrombus is from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), however, in most patients with suspected paradoxical embolism no evidence of a DVT is found.[3] Symptoms of a DVT will include unilateral leg swelling and pain, warmth, and redness of the affected area.[4] This is due to the blockage of blood attempting to return to the heart through the venous system.

Additional findings in a patient with a paradoxical embolism will be dependent upon where the emboli lodges and disrupts blood flow. Three important clinical manifestations that may be caused by paradoxical embolism include a stroke, migraine, and acute myocardial infarction, also known as a heart attack.[5] A stroke and migraine in the setting of a paradoxical embolism are caused by the emboli disrupting blood flow in a cerebral artery. A myocardial infarction in the setting of a paradoxical embolism are caused by the emboli disrupting blood flow in a coronary artery. Physical findings that should be evaluated include a comprehensive neurological examination for evaluation of stroke symptoms such as weakness, gait changes, slurred speech, and facial droop.[6]

Additionally, if a paradoxical embolism is suspected in a patient, findings consistent with a congenital heart defect that may lead to right-to-left shunting can be evaluated. These include digital clubbing due to chronic hypoxemia in distal extremities or a widely-split S2, a pathological heartbeat pattern where the second heart sound has two components.[7]

Pathophysiology

An embolism may be made from any one of numerous materials that may find itself in a blood vessel, including a piece of a thrombus, known as a thromboembolism, air from an intravenous catheter, fat globules from bone marrow, amniotic fluid during birth.[1] In order for an embolus to become a paradoxical embolus it must traverse from venous circulation, in the veins, to arterial circulation, in the arteries. There are many routes in which an embolism can traverse from the right (venous) side of the heart to the left (arterial) side of the heart. These routes include moving through a patent foramen ovale (a congenital hole connecting the right and left atria of the heart), a ventricular septal defect (a congenital hole connecting the ventricles), or a pulmonary arteriovenous fistula, where arteries in the lungs connect directly to veins without capillaries in between.[2][8] Although there are many routes an embolism may take to enter the arterial circulation, the term paradoxical embolism most commonly refers to a clot passing through a patent foramen ovale. The formen ovale is open during development of the heart in a developing fetus, and normally closes soon after birth - studies have found that patent foramen ovale is present in a significant portion of the population into adulthood.[9]

Once an embolus enters arterial circulation it continually travels down arteries to smaller vessels before lodging itself in vessels and stopping blood flow to the tissues supplied by that blood vessels. Often, the embolus will reach the brain and cause permanent stoppage of blood flow to a region of the brain, a feared complication of paradoxical embolism. This stoppage of blood flow in the brain, or ischemia, is called a cerebral infarct, also known as a stroke.[10]

Diagnosis

Resources suggest a paradoxical embolism should be expected when three findings are present simultaneously; a deep vein thrombosis (a thrombus occurring in a large vein, usually of the leg), a passageway or right-to-left shunt that allows an emboli across the heart, and evidence of arterial emboli.[6] Once suspicion is raised for a paradoxical embolism, a battery of tests may be ordered for the patient and a discussion regarding past medical history and family history is useful for identifying contributing risk factors.

History

It is essential to discuss if the patient has personal or family history of a patent foramen ovale or other congenital heart disease that may have allowed an embolus into arterial circulation. Additionally patients may be asked about a history of deep vein thrombosis or factors that contribute to DVT, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, prior heart attacks, or diabetes. Use of substance that make blood clots more likely such as tobacco or estrogen may also be discussed.[7]

Laboratory Studies and other Diagnostic Tests

Specific blood tests known as coagulation studies may be ordered. These tests measure how quickly a blood clot can form and may include PT, PTT, INR, and Protein C and S levels. A complete blood count (CBC) can also be ordered to test for low platelets.[6] An EKG may be started to evaluate for abnormal heart rhythms, especially atrial fibrillation which often cause traditional emboli to form in the heart. Arterial blood gas measurements and metabolic panels may also be drawn for the purpose of supportive measures.[7]

Imaging

Imaging can be done for various reasons during a suspected paradoxical embolism including scanning for a DVT that may have caused the emboli, evaluating the brain for ischemic changes secondary to embolism, and to evaluate for heart defect that could cause an emboli to enter systemic circulation.

Ultrasound, MRI imaging, or CT scans of the lower extremities help to identify a possible DVT, which provides evidence that an emboli may have come from venous circulation.[6] Although these imaging modalities are used to evaluate for venous thromboembolism, their use in detecting heart defects is limited. The use of MRI to detect cardiac shunts is "controversial" and that the use of CT is not recommended due to exposure to ionizing radiation and lack of functional imaging.[5]

It is reported that transesophageal echocardiography or TEE, is the best non-invasive option for diagnosing intracardiac shunts like a patent foramen ovale. Additionally, there is a need for a color flow Doppler study or the injection of agitated saline/contrast medium followed by a Valsalva maneuver to visualize flow of blood from the lower pressure venous system to the higher pressure arterial system.[5]

Similar to a TEE, a transcranial Doppler sonography study is also described as helping to evaluate for right-to-left shunts of the heart. However, it can also be used to detect other forms of right-to-left shunts including pulmonary arteriovenous malformations because it too needs agitated saline/contrast injected, but rather than imaging the heart, observes if any microemboli appear in the middle cerebral artery, an artery or the brain, following a valsalva maneuver.[5]

Ear oximetry is also described as a fairly accurate screening tool for a shunt. It measures the oxygen saturation of blood as it passes through the ear. Following a valsalva maneuver, pressure increases in the right heart, deoxygenated blood is shunted into arterial circulation, and a decrease in oxygen saturation can then be measured in the capillaries of the ear.[5]

Treatment

Current recommendation suggest that the two major goals of treatment include medical management of the thrombotic event to help prevent further thrombus/embolus formation and closure of the patent foramen ovale or other route that let to a pardoxical embolism.[7]

A paradoxical emboli should be medically managed similar to any other thromboembolism with medical anticoagulation. This is to prevent new or worsening blood clot formation that may occlude vessels and cause organ ischemia.[2] Some sources suggest anticoagulation with heparin be performed, while others give a list of reasonable drug options including anticoagulants like heparin and warfarin, anti-platelet therapy like aspirin and clopidogrel, and thrombolytic therapy like alteplase and streptokinase.[7][2] If an embolus is causing life or limb-threatening ischemia, is located in a reasonable location, and is first visualized with fluoroscopy, catheter embolectomy can be performed to retrieve the clot as well.[2]

Surgical closure of a patent foramen ovale or other atrial septal defects is often done through an out-patient, percutaneous, surgery that has few complications.[5] Although closure of a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect theoretically removes the pathway for an arterial embolus to enter venous circulation and cause a paradoxical embolism, data suggests that closing intracardiac shunts is no more effective than medical management alone in preventing strokes.[2]

Epidemiology

Although aging data has suggested paradoxical emboli may cause up to 47,000 strokes per year,[11] it is difficult to measure the actual rates of paradoxical emboli because it remains challenging to definitively diagnose the disease. Because many strokes have no known cause, an individual who has an embolic event, often a stroke, and is found to have patent foramen ovale or right-to-left shunt, the speculative diagnosis of paradoxical embolism is given to the patient.[5] Although no conclusive evidence has reported a true prevalence of the disease, data suggests that the presence of patent foramen ovales and other inter-cardiac shunts are associated with large increase in the prevalence of strokes of unknown etiology, suggesting paradoxical embolism may be the cause.[5] Regardless of true disease prevalence, the difficulties surrounding diagnosis may lead it to be an under-recognized etiology of strokes.

References

- 1 2 Kumar, Vinay; Abbas; Aster (2018). Robbins Basic Pathology, Tenth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 97–119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amin; Kresowik; Nicholson (2014). Current Therapy in Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Fifth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 629–631.

- ↑ Saremi, Farhood (Oct 13, 2014). "Paradoxical Embolism: Role of Imaging in Diagnosis and Treatment Planning". RadioGraphics. 34 (6): 1571–1592. doi:10.1148/rg.346135008. PMID 25310418.

- ↑ "Deep vein thrombosis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Windecker, Stephan; Storteky, Stefan; Meier, Bernhard (2014). "Paradoxical Embolism". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 64 (4): 403–415. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.063. PMID 25060377. Archived from the original on 2022-04-21. Retrieved 2022-07-09 – via PubMed.

- 1 2 3 4 "Paradoxical Embolism Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination, Complications". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2022-04-11. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hakman, Eryk N.; Cowling, Kathleen M. (2022), "Paradoxical Embolism", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262019, archived from the original on 2022-01-24, retrieved 2022-04-11

- ↑ Pollack, Jeffery (2021). Image-Guided Interventions: Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations. Elsevier. pp. 434–440.

- ↑ Maron, Bradley A.; Shekar, Prem S.; Goldhaber, Samuel Z. (2010-11-09). "Paradoxical Embolism". Circulation. 122 (19): 1968–1972. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961920. PMID 21060086. Archived from the original on 2022-04-18. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

- ↑ Kemp; Brown; Burns (2008). Neuropathology. Pathology: The Big Picture. McGraw Hill. pp. Chapter 11.

- ↑ Meacham, Robert R., III; Headley, A. Stacey; Bronze, Michael S.; Lewis, James B.; Rester, Michelle M. (1998-03-09). "Impending Paradoxical Embolism". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (5): 438–448. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.5.438. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 9508221.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |