Plummer–Vinson syndrome

| Plummer–Vinson syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Paterson–Brown–Kelly syndrome, Sideropenic dysphagia, | |

| |

| Angular stomatitis | |

Plummer–Vinson syndrome is a rare disease characterized by difficulty swallowing, iron-deficiency anemia, glossitis, cheilosis and esophageal webs.[1] Treatment with iron supplementation and mechanical widening of the esophagus generally provides an excellent outcome.

While exact data about the epidemiology is unknown, this syndrome has become extremely rare. The reduction in the prevalence of Plummer–Vinson syndrome has been hypothesized to be the result of improvements in nutritional status and availability in countries where the syndrome was previously described.[1] It generally occurs in perimenopausal women. Its identification and follow-up is considered relevant due to increased risk of squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus and pharynx.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Patients with Plummer–Vinson syndrome often have a burning sensation with the tongue and oral mucosa, and atrophy of lingual papillae produces a smooth, shiny, red, dorsum of the tongue. Symptoms include:

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Pain

- Weakness

- Odynophagia (painful swallowing)

- Atrophic glossitis

- Angular cheilitis

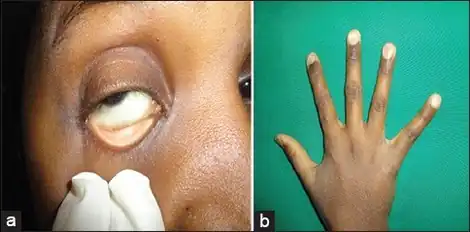

- Koilonychia (Abnormally thin nails, also called spoon nails)

- Splenomegaly (an enlarged spleen).

- Upper esophageal webs (post cricoid region - contrasts with Schatzki rings found at the lower end of esophagus).[2]

Serial contrasted gastrointestinal radiography or upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy may reveal the web in the esophagus. Blood tests demonstrate a hypochromic microcytic anemia that is consistent with an iron-deficiency anemia. Biopsy of involved mucosa typically reveals epithelial atrophy (shrinking) and varying amounts of submucosal chronic inflammation. Epithelial atypia or dysplasia may be present. It may also present as a post-cricoid malignancy which can be detected by loss of laryngeal crepitus. Laryngeal crepitus is found normally and is produced because the cricoid cartilage rubs against the vertebrae.

Causes

The cause of Plummer–Vinson syndrome is unknown; however, genetic factors and nutritional deficiencies may play a role. It is more common in women,[3] particularly in middle age, with a peak age over 50 years.

Diagnosis

The following clinical presentations may be used in the diagnosis of this condition.

- Dizziness

- Pallor of the conjunctiva and face

- Erythematous oral mucosa with burning sensation

- Breathlessness

- Atrophic and smooth tongue

- Peripheral rhagades around the oral cavity

The following tests are helpful in the diagnosis of Plummer–Vinson syndrome.

Lab tests

Complete blood cell counts, peripheral blood smears, and iron studies (e.g., serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, ferritin, and saturation percentage) to confirm iron deficiency, either with or without hypochromic microcytic anemia.

Imaging

Barium esophagography and videofluoroscopy will help to detect esophageal webs. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy will enable visual confirmation of esophageal webs. The webs occur due to sub-epithelial fibrosis.

Prevention

Good nutrition with adequate intake of iron may prevent this disorder. Good nutrition should also include balanced diet and exercise.

Treatment

Treatment is primarily aimed at correcting the iron-deficiency anemia. Patients with Plummer–Vinson syndrome should receive iron supplementation in their diet. This may improve dysphagia and pain.[1] If not, the web can be dilated with esophageal bougies during upper endoscopy to allow normal swallowing and passage of food.[4]

Complications

There is risk of perforation of the esophagus with the use of dilators for treatment. Furthermore, it is one of the risk factors for developing squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, esophagus, and hypopharynx.[5] Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk is also increased;[1] therefore, it is considered a premalignant process.[6]

Prognosis

Patients generally respond well to treatment. Iron supplementation usually resolves the anemia, and corrects the glossodynia (tongue pain).[1]

Epidemiology

PVS is an extremely rare condition, though its exact prevalence is unknown. While it is becoming less common in developed countries, the condition is increasingly found in developing countries, particularly in Asia.[6] However, it is very rarely seen in African countries, despite the relatively high prevalence of iron deficiency.[6]

History

The disease is named after two Americans: the physician Henry Stanley Plummer and the surgeon Porter Paisley Vinson.[7][8][9] It is occasionally known as Paterson-Kelly or Paterson-Brown Kelly syndrome in the UK, after Derek Brown-Kelly and Donald Ross Paterson.[1] However, Plummer–Vinson syndrome is still the most commonly used name.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Novacek G, Gottfried (2006). "Plummer-Vinson syndrome". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 1: 36. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-36. PMC 1586011. PMID 16978405.

- ↑ Sabiston 18th edition, p. 1078.

- ↑ "Plummer-Vinson syndrome: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ↑ Enomoto M, Kohmoto M, Arafa UA, et al. (2007). "Plummer-Vinson syndrome successfully treated by endoscopic dilatation". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 22 (12): 2348–51. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.03430.x. PMID 18031398.

- ↑ "Plummer-Vinson Syndrome". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Goel, A; Bakshi, SS; Soni, N; Chhavi, N (2017). "Iron deficiency anemia and Plummer-Vinson syndrome: current insights". Journal of Blood Medicine. 8: 175–184. doi:10.2147/JBM.S127801. PMC 5655134. PMID 29089792.

- ↑ synd/1777 at Who Named It?

- ↑ H. S. Plummer. Diffuse dilatation of the esophagus without anatomic stenosis (cardiospasm). A report of ninety-one cases. Journal of the American Medical Association, Chicago, 1912, 58: 2013-2015.

- ↑ P. P. Vinson. A case of cardiospasm with dilatation and angulation of the esophagus. Medical Clinics of North America, Philadelphia, PA., 1919, 3: 623-627.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|