Uveitis

| Uveitis | |

|---|---|

| |

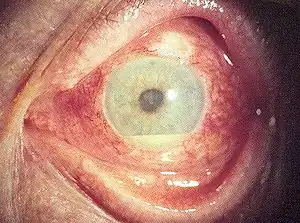

| Inflammation of the eye and keratic precipitates due to uveitis | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Blurry vision, floaters, eye pain, red eye, sensitivity to light[1] |

| Complications | Vision loss, glaucoma[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[1] |

| Types | Anterior, intermediate, posterior[1] |

| Causes | Infection: Cytomegalovirus, histoplasmosis, shingles, toxoplasmosis[1] Autoimmune: Behcet’s disease, psoriasis, ulcerative colitis, lupus[1] |

| Risk factors | Cigarette smoking[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and eye exam[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Retinoblastoma, lymphoma, glaucoma[2] |

| Treatment | Steroids, atropine, underlying cause[3][2] |

| Prognosis | Usually good with treatment[3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 3,000 per year[4] |

Uveitis is inflammation inside the eye.[1] Onset is usually sudden.[1] Early symptoms include blurry vision, floaters, eye pain, red eye, and sensitivity to light.[1] One or both eyes may be affected.[1] Complications may include loss of vision and glaucoma.[1][2]

Causes may be unknown, eye infection, or autoimmune conditions.[1][4] Risk factors include cigarette smoking.[1] The uvea is the iris, ciliary body, and choroid.[1] It is divided into anterior, intermediate, and posterior uveitis; though in panuveitis all parts may be affected.[1] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and a dilated eye exam.[1]

Treatment is usually with steroids, most commonly as eye drops such as prednisolone.[1][5] In severe cases steroids by mouth or by injection may be used.[5] If steroids are not effective other immunosuppressants such as methotrexate may be used.[5] Cycloplegics, such as atropine, may be used to help with pain and prevent complications.[3] In cases due to infection, specific treatment for the infection is also required.[2]

Uveitis affects about 1 in 3,000 people per year.[4] It most commonly occurs in those between the ages of 20–60; though any age may be affected.[1] Males and females are affected at similar rates.[4] It accounts for about 5-10% of vision problems globally and is the cause of up to 25% of blindness in the developing world.[4] With appropriate treatment outcomes are usually good.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of uveitis include the following;[6]

Anterior uveitis (iritis)

- Pain in the eye

- Redness of the eye

- Blurred vision

- Photophobia

- Irregular pupil

- Signs of anterior uveitis include dilated ciliary vessels, presence of cells and flare in the anterior chamber, and keratic precipitates ("KP") on the posterior surface of the cornea. In severe inflammation there may be evidence of a hypopyon. Old episodes of uveitis are identified by pigment deposits on lens, KPs, and festooned pupil on dilation of pupil.

- Busacca nodules, inflammatory nodules located on the surface of the iris in granulomatous forms of anterior uveitis such as Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI).[7]

- Synechia

Intermediate uveitis

Most common:

- Floaters, which are dark spots that float in the visual field

- Blurred vision

Intermediate uveitis usually affects one eye. Less common is the presence of pain and photophobia.[8]

Posterior uveitis

Inflammation in the back of the eye is commonly characterized by:

- Floaters

- Blurred vision

Causes

Uveitis is usually an isolated illness, but can be associated with many other medical conditions.[6] In anterior uveitis, no associated condition or syndrome is found in approximately one-half of cases. However, anterior uveitis is often one of the syndromes associated with HLA-B27. Presence of this type of HLA allele has a relative risk of evolving this disease by approximately 15%.[9]

The most common form of uveitis is acute anterior uveitis (AAU). It is most commonly associated with HLA-B27, which has important features: HLA-B27 AAU can be associated with ocular inflammation alone or in association with systemic disease. HLA-B27 AAU has characteristic clinical features including male preponderance, unilateral alternating acute onset, a non-granulomatous appearance, and frequent recurrences, whereas HLA-B27 negative AAU has an equivalent male to female onset, bilateral chronic course, and more frequent granulomatous appearance.[10] Rheumatoid arthritis is not uncommon in Asian countries as a significant association of uveitis.[11]

Noninfectious

Infectious

Uveitis may be an immune response to fight an infection inside the eye. While representing the minority of patients with uveitis, such possible infections include:

Systemic diseases

Systemic disorders that can be associated with uveitis include:[13][14]

- enthesitis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- psoriatic arthritis

- reactive arthritis

- Behçet's disease

- inflammatory bowel disease

- Whipple's disease

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- polyarteritis nodosa

- Kawasaki's disease

- chronic granulomatous disease

- sarcoidosis

- multiple sclerosis

- Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease

Drug related

- Rifabutin, a derivative of Rifampin, has been shown to cause uveitis.[15]

- Several reports suggest the use of quinolones, especially Moxifloxacin, may lead to uveitis.[16]

White Dot syndromes

Occasionally, uveitis is not associated with a systemic condition: the inflammation is confined to the eye and has unknown cause. In some of these cases, the presentation in the eye is characteristic of a described syndrome, which are called white dot syndromes, and include the following diagnoses:

Masquerade syndromes

Masquerade syndromes are those conditions that include the presence of intraocular cells but are not due to immune-mediated uveitis entities. These may be divided into neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions.

- Non-neoplastic:

- retinitis pigmentosa

- intraocular foreign body

- juvenile xanthogranuloma

- retinal detachment

- Neoplastic:

Pathophysiology

Immunologic factors

Onset of uveitis can broadly be described as a failure of the ocular immune system and the disease results from inflammation and tissue destruction. Uveitis is driven by the Th17 T cell sub-population that bear T-cell receptors specific for proteins found in the eye.[17] These are often not deleted centrally whether due to ocular antigen not being presented in the thymus (therefore not negatively selected) or a state of anergy is induced to prevent self targeting.[18][19]

Autoreactive T cells must normally be held in check by the suppressive environment produced by microglia and dendritic cells in the eye.[20] These cells produce large amounts of TGF beta and other suppressive cytokines, including IL-10, to prevent damage to the eye by reducing inflammation and causing T cells to differentiate to inducible T reg cells. Innate immune stimulation by bacteria and cellular stress is normally suppressed by myeloid suppression while inducible Treg cells prevent activation and clonal expansion of the autoreactive Th1 and Th17 cells that possess potential to cause damage to the eye.

Whether through infection or other causes, this balance can be upset and autoreactive T cells allowed to proliferate and migrate to the eye. Upon entry to the eye, these cells may be returned to an inducible Treg state by the presence of IL-10 and TGF-beta from microglia. Failure of this mechanism leads to neutrophil and other leukocyte recruitment from the peripheral blood through IL-17 secretion. Tissue destruction is mediated by non-specific macrophage activation and the resulting cytokine cascades.[21] Serum TNF-α is significantly elevated in cases while IL-6 and IL-8 are present in significantly higher quantities in the aqueous humour in patients with both quiescent and active uveitis.[22] These are inflammatory markers that non-specifically activate local macrophages causing tissue damage.

Genetics

The cause of non-infectious uveitis is unknown but there are some strong genetic factors that predispose disease onset including HLA-B27[23][24] and the PTPN22 genotype.[25]

Infections

Reactivation of herpes simplex, varicella zoster and other viruses are important causes of developing what was previously described as idiopathic anterior uveitis.[26] Bacterial infection may be another contributing factor in developing uveitis.[27]

Diagnosis

Examination may show an irregular pupil, dilated ciliary blood vessels, and cells in the anterior chamber.

Diagnosis also involves a dilated fundus examination to rule out posterior uveitis, which presents with white spots across the retina along with retinitis and vasculitis.

Laboratory testing is usually used to diagnose specific underlying diseases, including rheumatologic tests (e.g. antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor) and serology for infectious diseases (syphilis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis).

Major histocompatibility antigen testing may be performed to investigate genetic susceptibility to uveitis. The most common antigens include HLA-B27, HLA-A29 (in birdshot chorioretinopathy) and HLA-B51 (in Behçet disease).

Radiology X-ray may be used to show coexisting arthritis and chest X-ray may be helpful in sarcoidosis.

Classification

Uveitis is classified anatomically into anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitic forms—based on the part of the eye primarily affected.[28] Prior to the twentieth century, uveitis was typically referred to in English as "ophthalmia."[29]

- Anterior uveitis includes iridocyclitis and iritis. Iritis is the inflammation of the anterior chamber and iris. Iridocyclitis is inflammation of iris and the ciliary body with inflammation predominantly confined to ciliary body. Anywhere from two-thirds to 90% of uveitis cases are anterior in location (iritis). This condition can occur as a single episode and subside with proper treatment or may take on a recurrent or chronic nature.

- Intermediate uveitis, also known as pars planitis, consists of vitritis—which is inflammation of cells in the vitreous cavity, sometimes with snowbanking, or deposition of inflammatory material on the pars plana. There are also "snowballs," which are inflammatory cells in the vitreous.

- Posterior uveitis or chorioretinitis is the inflammation of the retina and choroid.

- Pan-uveitis is the inflammation of all layers of the uvea(Iris, ciliary body and choroid).

Treatment

Uveitis is typically treated with glucocorticoid steroids, either as topical eye drops (prednisolone) or by mouth.[30] Prior to the giving steroids, corneal ulcers should be ruled out. This is typically done using a fluorescence dye test.[31] In severe cases an injection of posterior subtenon triamcinolone acetate may also be given to reduce the swelling of the eye.[32] Antimetabolite medications, such as methotrexate are often used for recalcitrant or more aggressive cases of uveitis. Experimental treatments with infliximab or other anti-TNF infusions may prove helpful.

Topical cycloplegics, such as atropine or homatropine, may be used.

In the case of herpetic uveitis, anti-viral medications, such as valaciclovir or aciclovir, may be administered to treat the causative viral infection.[33]

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally good for those who receive prompt diagnosis and treatment, but serious complication including cataracts, glaucoma, band keratopathy, macular edema and permanent vision loss may result if left untreated. The type of uveitis, as well as its severity, duration, and responsiveness to treatment or any associated illnesses, all factor into the outlook.[6][34]

Epidemiology

Uveitis affects approximately 1 in 4500 people and is most common between the ages 20 to 60 with men and women affected equally. In western countries, anterior uveitis accounts for between 50% and 90% of uveitis cases. In Asian countries the proportion is between 28% and 50%.[35] Uveitis is estimated to be responsible for approximately 10%-20% of the blindness in the United States.[36]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Uveitis | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gueudry, J; Muraine, M (January 2018). "Anterior uveitis". Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 41 (1): e11–e21. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2017.11.003. PMID 29290458.

- 1 2 3 4 Duplechain, A; Conrady, CD; Patel, BC; Baker, S (January 2022). "Uveitis". PMID 31082037.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Tsirouki, T; Dastiridou, A; Symeonidis, C; Tounakaki, O; Brazitikou, I; Kalogeropoulos, C; Androudi, S (2018). "A Focus on the Epidemiology of Uveitis". Ocular immunology and inflammation. 26 (1): 2–16. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1196713. PMID 27467180.

- 1 2 3 Gamalero, L; Simonini, G; Ferrara, G; Polizzi, S; Giani, T; Cimaz, R (July 2019). "Evidence-Based Treatment for Uveitis". The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 21 (7): 475–479. PMID 31507124.

- 1 2 3 Mayo Clinic 2021.

- ↑ Abdullah Al-Fawaz; Ralph D Levinson (25 Feb 2010). "Uveitis, Anterior, Granulomatous". eMedicine from WebMD. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Babu BM, Rathinam SR (Jan–Feb 2010). "Intermediate uveitis". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 58 (1): 21–7. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.58469. PMC 2841370. PMID 20029143.

- ↑ Table 5-7 in: Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Larson T, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN (June 2011). "Emerging drugs for uveitis". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 16 (2): 309–22. doi:10.1517/14728214.2011.537824. PMC 3102121. PMID 21210752.

- ↑ Shah IA, Zuberi BF, Sangi SA, Abbasi SA (1999). "Systemic Manifestations of Iridocyclitis". Pak J Ophthalmol. 15 (2): 61–64. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ↑ "Zika Can Also Strike Eyes of Adults: Report". Consumer HealthDay. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ White G. "Uveitis." Archived 2013-08-23 at the Wayback Machine AllAboutVision.com. Retrieved August 20, 2006.

- ↑ McGonagle D, McDermott MF (August 2006). "A proposed classification of the immunological diseases". PLOS Medicine. 3 (8): e297. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030297. PMC 1564298. PMID 16942393.

- ↑ CDC: Department of Human Services (9 September 1994). "Uveitis Associated with Rifabutin Therapy". 43(35);658: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Eadie B, Etminan M, Mikelberg FS (January 2015). "Risk for uveitis with oral moxifloxacin: a comparative safety study". JAMA Ophthalmology. 133 (1): 81–4. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3598. PMID 25275293.

- ↑ Nian H, Liang D, Zuo A, Wei R, Shao H, Born WK, Kaplan HJ, Sun D (February 2012). "Characterization of autoreactive and bystander IL-17+ T cells induced in immunized C57BL/6 mice". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 53 (2): 897–905. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8297. PMC 3317428. PMID 22247477.

- ↑ Lambe T, Leung JC, Ferry H, Bouriez-Jones T, Makinen K, Crockford TL, Jiang HR, Nickerson JM, Peltonen L, Forrester JV, Cornall RJ, et al. (April 2007). "Limited peripheral T cell anergy predisposes to retinal autoimmunity". Journal of Immunology. 178 (7): 4276–83. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4276. PMID 17371984.

- ↑ Avichezer D, Grajewski RS, Chan CC, Mattapallil MJ, Silver PB, Raber JA, Liou GI, Wiggert B, Lewis GM, Donoso LA, Caspi RR, et al. (December 2003). "An immunologically privileged retinal antigen elicits tolerance: major role for central selection mechanisms". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 198 (11): 1665–76. doi:10.1084/jem.20030413. PMC 2194140. PMID 14657219.

- ↑ Forrester JV, Xu H, Kuffová L, Dick AD, McMenamin PG (March 2010). "Dendritic cell physiology and function in the eye". Immunological Reviews. 234 (1): 282–304. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00873.x. PMID 20193026. S2CID 21119296.

- ↑ Khera TK, Copland DA, Boldison J, Lait PJ, Szymkowski DE, Dick AD, Nicholson LB (May 2012). "Tumour necrosis factor-mediated macrophage activation in the target organ is critical for clinical manifestation of uveitis". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 168 (2): 165–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04567.x. PMC 3390517. PMID 22471277.

- ↑ Valentincic NV, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Kraut A, Korosec P, Hawlina M, Rothova A (2011). "Intraocular and serum cytokine profiles in patients with intermediate uveitis". Molecular Vision. 17: 2003–10. PMC 3154134. PMID 21850175.

- ↑ Wakefield D, Chang JH, Amjadi S, Maconochie Z, Abu El-Asrar A, McCluskey P (April 2011). "What is new HLA-B27 acute anterior uveitis?". Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 19 (2): 139–44. doi:10.3109/09273948.2010.542269. PMID 21428757. S2CID 20937369.

- ↑ Caspi RR (September 2010). "A look at autoimmunity and inflammation in the eye". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 120 (9): 3073–83. doi:10.1172/JCI42440. PMC 2929721. PMID 20811163.

- ↑ Burn GL, Svensson L, Sanchez-Blanco C, Saini M, Cope AP (December 2011). "Why is PTPN22 a good candidate susceptibility gene for autoimmune disease?". FEBS Letters. 585 (23): 3689–98. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.032. PMID 21515266.

- ↑ Jap A, Chee SP (November 2011). "Viral anterior uveitis". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 22 (6): 483–8. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834be021. PMID 21918442. S2CID 42582137.

- ↑ Dick AD (1 January 2012). "Road to fulfilment: taming the immune response to restore vision". Ophthalmic Research. 48 (1): 43–9. doi:10.1159/000335982. PMID 22398563.

- ↑ Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:509-516.

- ↑ Leffler CT, Schwartz SG, Stackhouse R, Davenport B, Spetzler K (December 2013). "Evolution and impact of eye and vision terms in written English". JAMA Ophthalmology. 131 (12): 1625–31. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.917. PMID 24337558. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23.

- ↑ Pato E, Muñoz-Fernández S, Francisco F, Abad MA, Maese J, Ortiz A, Carmona L (February 2011). "Systematic review on the effectiveness of immunosuppressants and biological therapies in the treatment of autoimmune posterior uveitis". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 40 (4): 314–23. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.05.008. PMID 20656330.

- ↑ "Fluorescein eye stain". NIH. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ BNF 45 March 2003

- ↑ Inkling. "Unsupported Browser". Inkling. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Uveitis from intelihealth". Archived from the original on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Chang JH, Wakefield D (December 2002). "Uveitis: a global perspective". Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 10 (4): 263–79. doi:10.1076/ocii.10.4.263.15592. PMID 12854035. S2CID 23658926.

- ↑ Gritz DC, Wong IG (March 2004). "Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study". Ophthalmology. 111 (3): 491–500, discussion 500. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.014. PMID 15019324.

External links

- Bodaghi, Bahram; LeHoang, Phuc (2017) [2009]. Uvéite (in français) (2nd ed.). Issy-les-Molineux, France: Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-2-294-74755-7. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- Mayo Clinic (2021). "Uveitis". Patient Care and Health Information. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |