History of Europe

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early European modern humans appear in the fossil record about 48,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic Era. Settled agriculture marked the Neolithic Era, which spread slowly across Europe from southeast to the north and west. The later Neolithic period saw the introduction of early metallurgy and the use of copper-based tools and weapons, and the building of megalithic structures, as exemplified by Stonehenge. During the Indo-European migrations, Europe saw migrations from the east and southeast. The period known as classical antiquity began with the emergence of the city-states of ancient Greece. Later, the Roman Empire came to dominate the entire Mediterranean basin. The Migration Period of the Germanic people began in the late 4th century AD and made gradual incursions into various parts of the Roman Empire.

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476 traditionally marks the start of the Middle Ages. While the Eastern Roman Empire would continue for another 1000 years, the former lands of the Western Empire would be fragmented into a number of different states. At the same time, the early Slavs began to become established as a distinct group in the central and eastern parts of Europe. The first great empire of the Middle Ages was the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne, while the Islamic conquest of Iberia established Al-Andalus. The Viking Age saw a second great migration of Norse peoples. Attempts to retake the Levant from the Muslim states that occupied it made the High Middle Ages the age of The Crusades, while the political system of feudalism came to its height. The Late Middle Ages were marked by large population declines, as Europe was threatened by the Bubonic Plague, as well as invasions by the Mongol peoples from the Eurasian Steppe. At the end of the Middle Ages, there was a transitional period, known as the Renaissance.

Early Modern Europe is usually dated to the end of the 15th century. Technological changes such as gunpowder and the printing press changed how warfare was conducted and how knowledge was preserved and disseminated. The Protestant Reformation saw the fragmentation of religious thought, leading to religious wars. The Age of Exploration led to colonization, and the exploitation of the people and resources of colonies brought resources and wealth to Europe. After 1800, the Industrial Revolution brought capital accumulation and rapid urbanization to Western Europe, while several countries transitioned away from absolutist rule to parliamentary regimes. The Age of Revolutions saw long-established political systems upset and turned over. In the 20th century, World War I led to a remaking of the map of Europe as the large Empires were broken up into nation-states. Lingering political issues would lead to World War II, during which Nazi Germany perpetrated the Holocaust. After World War II, during the Cold War, most of Europe became divided by the Iron Curtain in two military blocs: NATO and the Warsaw Pact. The post-war period saw decolonization as Western European colonial empires were dismantled. The post-war period also featured the gradual development of the European integration process, which led to the creation of the European Union; this extended to Eastern European countries after the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The 21st century saw the European debt crisis, the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Prehistory of Europe

Paleolithic

BisonsPoursuivisParDesLions.jpg.webp)

Homo erectus migrated from Africa to Europe before the emergence of modern humans. Homo erectus georgicus, which lived roughly 1.8 million years ago in Georgia, is the earliest hominid to have been discovered in Europe.[2] The earliest appearance of anatomically modern people in Europe has been dated to 45,000 BC, referred to as the Early European modern humans. Some locally developed transitional cultures (Uluzzian in Italy and Greece, Altmühlian in Germany, Szeletian in Central Europe and Châtelperronian in the southwest) use clearly Upper Palaeolithic technologies at very early dates.

Nevertheless, the definitive advance of these technologies is made by the Aurignacian culture, originating in the Levant (Ahmarian) and Hungary (first full Aurignacian). By 35,000 BC, the Aurignacian culture and its technology had extended through most of Europe. The last Neanderthals seem to have been forced to retreat to the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula. Around 29,000 BC a new technology/culture appeared in the western region of Europe: the Gravettian. This technology/culture has been theorised to have come with migrations of people from the Balkans (see Kozarnika).

Around 16,000 BC, Europe witnessed the appearance of a new culture, known as Magdalenian, possibly rooted in the old Gravettian. This culture soon superseded the Solutrean area and the Gravettian of mainly France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Ukraine. The Hamburg culture prevailed in Northern Europe in the 14th and the 13th millennium BC as the Creswellian (also termed the British Late Magdalenian) did shortly after in the British Isles. Around 12,500 BC, the Würm glaciation ended. Magdalenian culture persisted until c. 10,000 BC, when it quickly evolved into two microlithist cultures: Azilian (Federmesser), in Spain and southern France, and then Sauveterrian, in southern France and Tardenoisian in Central Europe, while in Northern Europe the Lyngby complex succeeded the Hamburg culture with the influence of the Federmesser group as well.

Neolithic and Copper Age

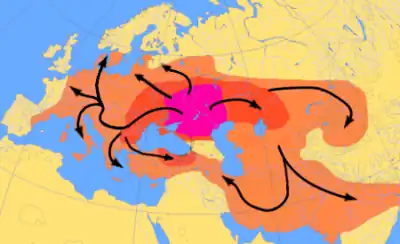

Evidence of permanent settlement dates from the 8th millennium BC in the Balkans. The Neolithic reached Central Europe in the 6th millennium BC and parts of Northern Europe in the 5th and 4th millenniums BC. The modern indigenous populations of Europe are largely descended from three distinct lineages: Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, a derivative of the Cro-Magnon population, Early European Farmers who migrated from Anatolia during the Neolithic Revolution, and Yamnaya pastoralists who expanded into Europe in the context of the Indo-European expansion.[3] The Indo-European migrations started in Southeast Europe at around c. 4200 BC. through the areas around the Black sea and the Balkan peninsula. In the next 3000 years the Indo-European languages expanded through Europe.

Around this time, in the 5th millennium BC the Varna culture evolved. In 4700 – 4200 BC, the Solnitsata town, believed to be the oldest prehistoric town in Europe, flourished.[4][5]

Neolithic expansion in Europe, 7000-4000 BC

Neolithic expansion in Europe, 7000-4000 BC Late Neolithic Europe, c. 5000-3500 BC

Late Neolithic Europe, c. 5000-3500 BC Indo-European migrations from c. 4000-1500 BC according to the Kurgan hypothesis

Indo-European migrations from c. 4000-1500 BC according to the Kurgan hypothesis Late Bronze Age Europe, c. 1300-900 BC

Late Bronze Age Europe, c. 1300-900 BC

Ancient Europe

Bronze Age

The first well-known literate civilization in Europe was the Minoan civilization that arose on the island of Crete and flourished from approximately the 27th century BC to the 15th century BC.[6]

The Minoans were replaced by the Mycenaean civilization which flourished during the period roughly between 1600 BC, when Helladic culture in mainland Greece was transformed under influences from Minoan Crete, and 1100 BC. The major Mycenaean cities were Mycenae and Tiryns in Argolis, Pylos in Messenia, Athens in Attica, Thebes and Orchomenus in Boeotia, and Iolkos in Thessaly. In Crete, the Mycenaeans occupied Knossos. Mycenaean settlement sites also appeared in Epirus,[7][8] Macedonia,[9][10] on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of Asia Minor, the Levant,[11] Cyprus[12] and Italy.[13][14] Mycenaean artefacts have been found well outside the limits of the Mycenean world.

Quite unlike the Minoans, whose society benefited from trade, the Mycenaeans advanced through conquest. Mycenaean civilization was dominated by a warrior aristocracy. Around 1400 BC, the Mycenaeans extended their control to Crete, the centre of the Minoan civilization, and adopted a form of the Minoan script (called Linear A) to write their early form of Greek in Linear B.

The Mycenaean civilization perished with the collapse of Bronze-Age civilization on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. The collapse is commonly attributed to the Dorian invasion, although other theories describing natural disasters and climate change have been advanced as well. Whatever the causes, the Mycenaean civilization had definitely disappeared after LH III C, when the sites of Mycenae and Tiryns were again destroyed and lost their importance. This end, during the last years of the 12th century BC, occurred after a slow decline of the Mycenaean civilization, which lasted many years before dying out. The beginning of the 11th century BC opened a new context, that of the protogeometric, the beginning of the geometric period, the Greek Dark Ages of traditional historiography.

The Bronze Age collapse may be seen in the context of a technological history that saw the slow spread of ironworking technology from present-day Bulgaria and Romania in the 13th and the 12th centuries BC.[15]

Classical Antiquity

Ancient Greece

The Hellenic civilisation was a collection of city-states or poleis with different governments and cultures that achieved notable developments in government, philosophy, science, mathematics, politics, sports, theatre and music.

The most powerful city-states were Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, and Syracuse. Athens was a powerful Hellenic city-state and governed itself with an early form of direct democracy invented by Cleisthenes; the citizens of Athens voted on legislation and executive bills themselves. Athens was the home of Socrates,[16] Plato, and the Platonic Academy.

The Hellenic city-states established colonies on the shores of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea (Asian Minor, Sicily, and Southern Italy in Magna Graecia). By the late 6th century BC, the Greek city states in Asia Minor had been incorporated into the Persian Empire, while the latter had made territorial gains in the Balkans (such as Macedon, Thrace, Paeonia, etc.) and Eastern Europe proper as well. In the course of the 5th century BC, some of the Greek city states attempted to overthrow Persian rule in the Ionian Revolt, which failed. This sparked the first Persian invasion of mainland Greece. At some point during the ensuing Greco-Persian Wars, namely during the Second Persian invasion of Greece, and precisely after the Battle of Thermopylae and the Battle of Artemisium, almost all of Greece to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth had been overrun by the Persians,[17] but the Greek city states reached a decisive victory at the Battle of Plataea. With the end of the Greco-Persian wars, the Persians were eventually forced to withdraw from their territories in Europe. The Greco-Persian Wars and the victory of the Greek city states directly influenced the entire further course of European history and would set its further tone. Some Greek city-states formed the Delian League to continue fighting Persia, but Athens' position as leader of this league led Sparta to form the rival Peloponnesian League. The Peloponnesian Wars ensued, and the Peloponnesian League was victorious. Subsequently, discontent with Spartan hegemony led to the Corinthian War and the defeat of Sparta at the Battle of Leuctra. At the same time at the north ruled the Thracian Odrysian Kingdom between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD.

Hellenic infighting left Greek city states vulnerable, and Philip II of Macedon united the Greek city states under his control. The son of Philip II, known as Alexander the Great, invaded neighboring Persia, toppled and incorporated its domains, as well as invading Egypt and going as far off as India, increasing contact with people and cultures in these regions that marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

After the death of Alexander the Great, his empire split into multiple kingdoms ruled by his generals, the Diadochi. The Diadochi fought against each other in a series of conflicts called the Wars of the Diadochi. In the beginning of the 2nd century BC, only three major kingdoms remained: the Ptolemaic Egypt, the Seleucid Empire and Macedonia. These kingdoms spread Greek culture to regions as far away as Bactria.[18]

Ancient Rome

Much of Greek learning was assimilated by the nascent Roman state as it expanded outward from Italy, taking advantage of its enemies' inability to unite: the only challenge to Roman ascent came from the Phoenician colony of Carthage, and its defeats in the three Punic Wars marked the start of Roman hegemony. First governed by kings, then as a senatorial republic (the Roman Republic), Rome finally became an empire at the end of the 1st century BC, under Augustus and his authoritarian successors.

The Roman Empire had its centre in the Mediterranean, controlling all the countries on its shores; the northern border was marked by the Rhine and Danube rivers. Under the emperor Trajan (2nd century AD) the empire reached its maximum expansion, controlling approximately 5,900,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) of land surface, including Italia, Gallia, Dalmatia, Aquitania, Britannia, Baetica, Hispania, Thrace, Macedonia, Greece, Moesia, Dacia, Pannonia, Egypt, Asia Minor, Cappadocia, Armenia, Caucasus, North Africa, Levant and parts of Mesopotamia. Pax Romana, a period of peace, civilisation and an efficient centralised government in the subject territories ended in the 3rd century, when a series of civil wars undermined Rome's economic and social strength.

In the 4th century, the emperors Diocletian and Constantine were able to slow down the process of decline by splitting the empire into a Western part with a capital in Rome and an Eastern part with the capital in Byzantium, or Constantinople (now Istanbul). Constantinople is generally considered to be the center of "Eastern Orthodox civilization".[19][20] Whereas Diocletian severely persecuted Christianity, Constantine declared an official end to state-sponsored persecution of Christians in 313 with the Edict of Milan, thus setting the stage for the Church to become the state church of the Roman Empire in about 380.

The Roman Empire had been repeatedly attacked by invading armies from Northern Europe and in 476, Rome finally fell. Romulus Augustus, the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, surrendered to the Germanic King Odoacer.

Late Antiquity and Migration Period

When Emperor Constantine had reconquered Rome under the banner of the cross in 312, he soon afterwards issued the Edict of Milan in 313 (preceded by the Edict of Serdica in 311), declaring the legality of Christianity in the Roman Empire. In addition, Constantine officially shifted the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to the Greek town of Byzantium, which he renamed Nova Roma – it was later named Constantinople ("City of Constantine").

Theodosius I, who had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, would be the last emperor to preside over a united Roman Empire, until his death in 395. The empire was split into two halves: the Western Roman Empire centred in Ravenna, and the Eastern Roman Empire (later to be referred to as the Byzantine Empire) centred in Constantinople. The Roman Empire was repeatedly attacked by Hunnic, Germanic, Slavic and other "barbarian" tribes (see: Migration Period), and in 476 finally the Western part fell to the Heruli chieftain Odoacer.

Roman authority in the Western part of the empire had collapsed, and a power vacuum left in the wake of this collapse; the central organization, institutions, laws and power of Rome had broken down, resulting in many areas being open to invasion by migrating tribes. Over time, feudalism and manorialism arose, providing for division of land and labour, as well as a broad if uneven hierarchy of law and protection. These localised hierarchies were based on the bond of common people to the land on which they worked, and to a lord, who would provide and administer both local law to settle disputes among the peasants, as well as protection from outside invaders.

The western provinces soon were to be dominated by three great powers: first, the Franks (Merovingian dynasty) in Francia 481–843 AD, which covered much of present France and Germany; second, the Visigothic kingdom 418–711 AD in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain); and third, the Ostrogothic kingdom 493–553 AD in Italy and parts of the western Balkans. The Ostrogoths were later replaced by the Kingdom of the Lombards 568–774 AD. Although these powers covered large territories, they did not have the great resources and bureaucracy of the Roman empire to control regions and localities; more power and responsibilities were left to local lords. On the other hand, it also meant more freedom, particularly in more remote areas.

In Italy, Theodoric the Great began the cultural romanisation of the new world he had constructed. He made Ravenna a centre of Romano-Greek culture of art and his court fostered a flowering of literature and philosophy in Latin. In Iberia, King Chindasuinth created the Visigothic Code. [21]

In the Eastern part the dominant state was the remaining Eastern Roman Empire.

In the feudal system, new princes and kings arose, the most powerful of which was arguably the Frankish ruler Charlemagne. In 800, Charlemagne, reinforced by his massive territorial conquests, was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III, solidifying his power in western Europe. Charlemagne's reign marked the beginning of a new Germanic Roman Empire in the west, the Holy Roman Empire. Outside his borders, new forces were gathering. The Kievan Rus' were marking out their territory, a Great Moravia was growing, while the Angles and the Saxons were securing their borders.

For the duration of the 6th century, the Eastern Roman Empire was embroiled in a series of deadly conflicts, first with the Persian Sassanid Empire (see Roman–Persian Wars), followed by the onslaught of the arising Islamic Caliphate (Rashidun and Umayyad). By 650, the provinces of Egypt, Palestine and Syria were lost to the Muslim forces, followed by Hispania and southern Italy in the 7th and 8th centuries (see Muslim conquests). The Arab invasion from the east was stopped after the intervention of the Bulgarian Empire (see Han Tervel).

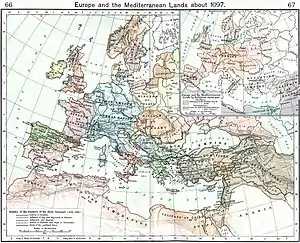

Post-classical Europe

The Middle Ages are commonly dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (or by some scholars, before that) in the 5th century to the beginning of the early modern period in the 16th century marked by the rise of nation states, the division of Western Christianity in the Reformation, the rise of humanism in the Italian Renaissance, and the beginnings of European overseas expansion which allowed for the Columbian Exchange.[22][23]

Byzantium

Many consider Emperor Constantine I (reigned 306–337) to be the first "Byzantine emperor". It was he who moved the imperial capital in 324 from Nicomedia to Byzantium, which re-founded as Constantinople, or Nova Roma ("New Rome").[24] The city of Rome itself had not served as the capital since the reign of Diocletian (284–305). Some date the beginnings of the Empire to the reign of Theodosius I (379–395) and Christianity's official supplanting of the pagan Roman religion, or following his death in 395, when the empire was split into two parts, with capitals in Rome and Constantinople. Others place it yet later in 476, when Romulus Augustulus, traditionally considered the last western emperor, was deposed, thus leaving sole imperial authority with the emperor in the Greek East. Others point to the reorganisation of the empire in the time of Heraclius (c. 620) when Latin titles and usages were officially replaced with Greek versions. In any case, the changeover was gradual and by 330, when Constantine inaugurated his new capital, the process of hellenization and increasing Christianisation was already under way. The Empire is generally considered to have ended after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Plague of Justinian was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years 541–542. It is estimated that the Plague of Justinian killed as many as 100 million people.[25][26] It caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and 700.[27] It also may have contributed to the success of the Muslim conquests.[28][29] During most of its existence, the Byzantine Empire was one of the most powerful economic, cultural, and military forces in Europe, and Constantinople was one of the largest and wealthiest cities in Europe.[30]

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages span roughly five centuries from 500 to 1000.[31]

In the East and Southeast of Europe new dominant states formed: the Avar Khaganate (567–after 822), Old Great Bulgaria (632–668), the Khazar Khaganate (c. 650–969) and Danube Bulgaria (founded by Asparuh in 680) were constantly rivaling the hegemony of the Byzantine Empire.

From the 7th century Byzantine history was greatly affected by the rise of Islam and the Caliphates. Muslim Arabs first invaded historically Roman territory under Abū Bakr, first Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, who entered Roman Syria and Roman Mesopotamia. As the Byzantines and neighboring Sasanids were severely weakened by the time, amongst the most important reason(s) being the protracted, centuries-lasting and frequent Byzantine–Sasanian wars, which included the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, under Umar, the second Caliph, the Muslims entirely toppled the Sasanid Persian Empire, and decisively conquered Syria and Mesopotamia, as well as Roman Palestine, Roman Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor and Roman North Africa. In the mid 7th century AD, following the Muslim conquest of Persia, Islam penetrated into the Caucasus region, of which parts would later permanently become part of Russia.[32] This trend, which included the conquests by the invading Muslim forces and by that the spread of Islam as well continued under Umar's successors and under the Umayyad Caliphate, which conquered the rest of Mediterranean North Africa and most of the Iberian Peninsula. Over the next centuries Muslim forces were able to take further European territory, including Cyprus, Malta, Crete, and Sicily and parts of southern Italy.[33]

The Muslim conquest of Hispania began when the Moors invaded the Christian Visigothic kingdom of Hispania in 711, under the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad. They landed at Gibraltar on 30 April and worked their way northward. Tariq's forces were joined the next year by those of his Arab superior, Musa ibn Nusair. During the eight-year campaign most of the Iberian Peninsula was brought under Muslim rule – save for small areas in the northwest (Asturias) and largely Basque regions in the Pyrenees. In 711, Visigothic Hispania was weakened because it was immersed in a serious internal crisis caused by a war of succession to the throne. The Muslims took advantage of the crisis within the Hispano-Visigothic society to carry out their conquests. This territory, under the Arab name Al-Andalus, became part of the expanding Umayyad empire.

The second siege of Constantinople (717) ended unsuccessfully after the intervention of Tervel of Bulgaria and weakened the Umayyad dynasty and reduced their prestige. In 722 Don Pelayo formed an army of 300 Astur soldiers, to confront Munuza's Muslim troops. In the battle of Covadonga, the Astures defeated the Arab-Moors, who decided to retire. The Christian victory marked the beginning of the Reconquista and the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias, whose first sovereign was Don Pelayo. The conquerors intended to continue their expansion in Europe and move northeast across the Pyrenees, but were defeated by the Frankish leader Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732. The Umayyads were overthrown in 750 by the 'Abbāsids,[34] and, in 756, the Umayyads established an independent emirate in the Iberian Peninsula.[35]

Feudal Christendom

The Holy Roman Empire emerged around 800, as Charlemagne, King of the Franks and part of the Carolingian dynasty, was crowned by the pope as emperor. His empire based in modern France, the Low Countries and Germany expanded into modern Hungary, Italy, Bohemia, Lower Saxony and Spain. He and his father received substantial help from an alliance with the Pope, who wanted help against the Lombards.[36] His death marked the beginning of the end of the dynasty, which collapsed entirely by 888. The fragmentation of power led to semi-autonomy in the region, and has been defined as a critical starting point for the formation of states in Europe.[37]

To the east, Bulgaria was established in 681 and became the first Slavic country. The powerful Bulgarian Empire was the main rival of Byzantium for control of the Balkans for centuries and from the 9th century became the cultural centre of Slavic Europe. The Empire created the Cyrillic script during the 9th century AD, at the Preslav Literary School, and experienced the Golden Age of Bulgarian cultural prosperity during the reign of emperor Simeon I the Great (893–927). Two states, Great Moravia and Kievan Rus', emerged among the Slavic peoples respectively in the 9th century. In the late 9th and 10th centuries, northern and western Europe felt the burgeoning power and influence of the Vikings who raided, traded, conquered and settled swiftly and efficiently with their advanced seagoing vessels such as the longships. The Vikings had left a cultural influence on the Anglo-Saxons and Franks as well as the Scots.[38] The Hungarians pillaged mainland Europe, the Pechenegs raided Bulgaria, Rus States and the Arab states. In the 10th century independent kingdoms were established in Central Europe including Poland and the newly settled Kingdom of Hungary. The Kingdom of Croatia also appeared in the Balkans. The subsequent period, ending around 1000, saw the further growth of feudalism, which weakened the Holy Roman Empire.

In eastern Europe, Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 921, after Almış I converted to Islam under the missionary efforts of Ahmad ibn Fadlan.[39]

Slavery in the early medieval period had mostly died out in western Europe by about the year 1000 AD, replaced by serfdom. It lingered longer in England and in peripheral areas linked to the Muslim world, where slavery continued to flourish. Church rules suppressed slavery of Christians. Most historians argue the transition was quite abrupt around 1000, but some see a gradual transition from about 300 to 1000.[40]

High Middle Ages

In 1054, the East–West Schism occurred between the two remaining Christian seats in Rome and Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

The High Middle Ages of the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries show a rapidly increasing population of Europe, which caused great social and political change from the preceding era. By 1250, the robust population increase greatly benefited the economy, reaching levels it would not see again in some areas until the 19th century.[41]

From about the year 1000 onwards, Western Europe saw the last of the barbarian invasions and became more politically organized. The Vikings had settled in Britain, Ireland, France and elsewhere, whilst Norse Christian kingdoms were developing in their Scandinavian homelands. The Magyars had ceased their expansion in the 10th century, and by the year 1000, the Roman Catholic Apostolic Kingdom of Hungary was recognised in central Europe. With the brief exception of the Mongol invasions, major barbarian incursions ceased.

Bulgarian sovereignty was re-established with the anti-Byzantine uprising of the Bulgarians and Vlachs in 1185. The crusaders invaded the Byzantine empire, captured Constantinople in 1204 and established their Latin Empire. Kaloyan of Bulgaria defeated Baldwin I, Latin Emperor of Constantinople, in the Battle of Adrianople on 14 April 1205. The reign of Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria led to maximum territorial expansion and that of Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria to a Second Golden Age of Bulgarian culture. The Byzantine Empire was fully re-established in 1261.

In the 11th century, populations north of the Alps began to settle new lands. Vast forests and marshes of Europe were cleared and cultivated. At the same time settlements moved beyond the traditional boundaries of the Frankish Empire to new frontiers in Europe, beyond the Elbe river, tripling the size of Germany in the process. Crusaders founded European colonies in the Levant, the majority of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered from the Muslims, and the Normans colonised southern Italy, all part of the major population increase and resettlement pattern.

The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and artistic works. The most famous are the great cathedrals as expressions of Gothic architecture, which evolved from Romanesque architecture. This age saw the rise of modern nation-states in Western Europe and the ascent of the famous Italian city-states, such as Florence and Venice. The influential popes of the Catholic Church called volunteer armies from across Europe to a series of Crusades against the Seljuq Turks, who occupied the Holy Land. The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle led Thomas Aquinas and other thinkers to develop the philosophy of Scholasticism.

Holy wars

After the East–West Schism, Western Christianity was adopted by the newly created kingdoms of Central Europe: Poland, Hungary and Bohemia. The Roman Catholic Church developed as a major power, leading to conflicts between the Pope and emperor. The geographic reach of the Roman Catholic Church expanded enormously due to the conversions of pagan kings (Scandinavia, Lithuania, Poland, Hungary), the Christian Reconquista of Al-Andalus, and the crusades. Most of Europe was Roman Catholic in the 15th century.

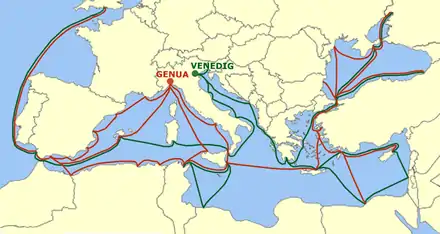

Early signs of the rebirth of civilization in western Europe began to appear in the 11th century as trade started again in Italy, leading to the economic and cultural growth of independent city-states such as Venice and Florence; at the same time, nation-states began to take form in places such as France, England, Spain, and Portugal, although the process of their formation (usually marked by rivalry between the monarchy, the aristocratic feudal lords and the church) actually took several centuries. These new nation-states began writing in their own cultural vernaculars, instead of the traditional Latin. Notable figures of this movement would include Dante Alighieri and Christine de Pizan. The Holy Roman Empire, essentially based in Germany and Italy, further fragmented into a myriad of feudal principalities or small city states, whose subjection to the emperor was only formal.

The 14th century, when the Mongol Empire came to power, is often called the Age of the Mongols. Mongol armies expanded westward under the command of Batu Khan. Their western conquests included almost all of Russia (save Novgorod, which became a vassal),[42] and the Kipchak-Cuman Confederation. Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland managed to remain sovereign states. Mongolian records indicate that Batu Khan was planning a complete conquest of the remaining European powers, beginning with a winter attack on Austria, Italy and Germany, when he was recalled to Mongolia upon the death of Great Khan Ögedei. Most historians believe only his death prevented the complete conquest of Europe. The areas of Eastern Europe and most of Central Asia that were under direct Mongol rule became known as the Golden Horde. Under Uzbeg Khan, Islam became the official religion of the region in the early 14th century.[43] The invading Mongols, together with their mostly Turkic subjects, were known as Tatars. In Russia, the Tatars ruled the various states of the Rus' through vassalage for over 300 years.

In the Northern Europe, Konrad of Masovia gave Chełmno to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for a Crusade against the Old Prussians and Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword were defeated by the Lithuanians, so in 1237 Gregory IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the Livonian Order. By the middle of the century, the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Prussians before converting the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades. The order also came into conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church of the Pskov and Novgorod Republics. In 1240 the Orthodox Novgorod army defeated the Catholic Swedes in the Battle of the Neva, and, two years later, they defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle on the Ice. The Union of Krewo in 1386, bringing two major changes in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: conversion to Catholicism and establishment of a dynastic union between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland marked both the greatest territorial expansion of the Grand Duchy and the defeat of the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410.

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages spanned around the 14th and late 15th centuries.[44] Around 1300, centuries of European prosperity and growth came to a halt. A series of famines and plagues, such as the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the Black Death, killed people in a matter of days, reducing the population of some areas by half as many survivors fled. Kishlansky reports:

- The Black Death touched every aspect of life, hastening a process of social, economic, and cultural transformation already underway.... Fields were abandoned, workplaces stood idle, international trade was suspended. Traditional bonds of kinship, village, and even religion were broken amid the horrors of death, flight, and failed expectations. "People cared no more for dead men than we care for dead goats," wrote one survivor.[45]

Depopulation caused labor to become scarcer; the survivors were better paid and peasants could drop some of the burdens of feudalism. There was also social unrest; France and England experienced serious peasant risings including the Jacquerie and the Peasants' Revolt. The unity of the Catholic Church was shattered by the Great Schism. Collectively these events have been called the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.[46]

Beginning in the 14th century, the Baltic Sea became one of the most important trade routes. The Hanseatic League, an alliance of trading cities, facilitated the absorption of vast areas of Poland, Lithuania, and Livonia into trade with other European countries. This fed the growth of powerful states in this part of Europe including Poland–Lithuania, Hungary, Bohemia, and Muscovy later on. The conventional end of the Middle Ages is usually associated with the fall of the city of Constantinople and of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Turks made the city the capital of their Ottoman Empire, which lasted until 1922 and included Egypt, Syria, and most of the Balkans. The Ottoman wars in Europe marked an essential part of the history of the continent.

A key 15th-century development was the advent of the movable type of printing press circa 1439 in Mainz,[47] building upon the impetus provided by the prior introduction of paper from China via the Arabs in the High Middle Ages.[48] The adoption of the technology across the continent at dazzling speed for the remaining part of the 15th century would usher a revolution and by 1500 over 200 cities in Europe had presses that printed between 8 and 20 million books.[47]

Early modern Europe

The Early Modern period spans the centuries between the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution, roughly from 1500 to 1800, or from the discovery of the New World in 1492 to the French Revolution in 1789. The period is characterised by the rise in importance of science and increasingly rapid technological progress, secularised civic politics, and the nation state. Capitalist economies began their rise, and the early modern period also saw the rise and dominance of the economic theory of mercantilism. As such, the early modern period represents the decline and eventual disappearance, in much of the European sphere, of feudalism, serfdom and the power of the Catholic Church. The period includes the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution, the Protestant Reformation, the disastrous Thirty Years' War, the European colonisation of the Americas and the European witch-hunts.

Renaissance

Despite these crises, the 14th century was also a time of great progress within the arts and sciences. A renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman led to the Italian Renaissance, a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period. Beginning in Italy, and spreading to the north, west and middle Europe during a cultural lag of some two and a half centuries, its influence affected literature, philosophy, art, politics, science, history, religion, and other aspects of intellectual inquiry. The Humanists saw their repossession of a great past as a Renaissance – a rebirth of civilization itself.[49] Important political precedents were also set in this period. Niccolò Machiavelli's political writing in The Prince influenced later absolutism and realpolitik. Also important were the many patrons who ruled states and used the artistry of the Renaissance as a sign of their power.

The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe starting towards the second half of the Renaissance period, with the 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus publication De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) often cited as its beginning.

Exploration and trade

.jpg.webp)

Toward the end of the period, an era of discovery began. The growth of the Ottoman Empire, culminating in the fall of Constantinople in 1453, cut off trading possibilities with the east. Western Europe was forced to discover new trading routes, as happened with Columbus' travel to the Americas in 1492, and Vasco da Gama's circumnavigation of India and Africa in 1498.

The numerous wars did not prevent European states from exploring and conquering wide portions of the world, from Africa to Asia and the newly discovered Americas. In the 15th century, Portugal led the way in geographical exploration along the coast of Africa in search of a maritime route to India, followed by Spain near the close of the 15th century, dividing their exploration of the world according to the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494.[50] They were the first states to set up colonies in America and European trading posts (factories) along the shores of Africa and Asia, establishing the first direct European diplomatic contacts with Southeast Asian states in 1511, China in 1513 and Japan in 1542. In 1552, Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible conquered two major Tatar khanates, the Khanate of Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanate. The Yermak's voyage of 1580 led to the annexation of the Tatar Siberian Khanate into Russia, and the Russians would soon after conquer the rest of Siberia, steadily expanding to the east and south over the next centuries. Oceanic explorations soon followed by France, England and the Netherlands, who explored the Portuguese and Spanish trade routes into the Pacific Ocean, reaching Australia in 1606[51] and New Zealand in 1642.

Reformation

With the development of the printing press, new ideas spread throughout Europe and challenged traditional doctrines in science and theology. Simultaneously, the Protestant Reformation under German Martin Luther questioned Papal authority. The most common dating of the Reformation begins in 1517, when Luther published The Ninety-Five Theses, and concludes in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia that ended years of European religious wars.[52]

During this period corruption in the Catholic Church led to a sharp backlash in the Protestant Reformation. It gained many followers especially among princes and kings seeking a stronger state by ending the influence of the Catholic Church. Figures other than Martin Luther began to emerge as well like John Calvin whose Calvinism had influence in many countries and King Henry VIII of England who broke away from the Catholic Church in England and set up the Anglican Church. These religious divisions brought on a wave of wars inspired and driven by religion but also by the ambitious monarchs in Western Europe who were becoming more centralized and powerful.

The Protestant Reformation also led to a strong reform movement in the Catholic Church called the Counter-Reformation, which aimed to reduce corruption as well as to improve and strengthen Catholic dogma. Two important groups in the Catholic Church who emerged from this movement were the Jesuits, who helped keep Spain, Portugal, Poland, and other European countries within the Catholic fold, and the Oratorians of Saint Philip Neri, who ministered to the faithful in Rome, restoring their confidence in the Church of Jesus Christ that subsisted substantially in the Church of Rome. Still, the Catholic Church was somewhat weakened by the Reformation, portions of Europe were no longer under its sway and kings in the remaining Catholic countries began to take control of the church institutions within their kingdoms.

Unlike many European countries, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Hungary were more tolerant. While still enforcing the predominance of Catholicism, they continued to allow the large religious minorities to maintain their faiths, traditions and customs. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth became divided among Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, Jews and a small Muslim population.

Another development was the idea of 'European superiority'. There was a movement by some such as Montaigne that regarded the non-Europeans as a better, more natural and primitive people. Post services were founded all over Europe, which allowed a humanistic interconnected network of intellectuals across Europe, despite religious divisions. However, the Roman Catholic Church banned many leading scientific works; this led to an intellectual advantage for Protestant countries, where the banning of books was regionally organised. Francis Bacon and other advocates of science tried to create unity in Europe by focusing on the unity in nature.1 In the 15th century, at the end of the Middle Ages, powerful sovereign states were appearing, built by the New Monarchs who were centralising power in France, England, and Spain. On the other hand, the Parliament in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth grew in power, taking legislative rights from the Polish king. The new state power was contested by parliaments in other countries especially England. New kinds of states emerged which were co-operation agreements among territorial rulers, cities, farmer republics and knights.

Mercantilism and colonial expansion

The Iberian kingdoms were able to dominate colonial activity in the 16th century. The Portuguese forged the first global empire in the 15th and 16th century, whilst during the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century, the crown of Castile (and the overarching Hispanic Monarchy, including Portugal from 1580 to 1640) became the most powerful empire in the world. Spanish dominance in America was increasingly challenged by British, French, Dutch and Swedish colonial efforts of the 17th and 18th centuries. New forms of trade and expanding horizons made new forms of government, law and economics necessary.

Colonial expansion continued in the following centuries (with some setbacks, such as successful wars of independence in the British American colonies and then later Haiti, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and others amid European turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars). Spain had control of a large part of North America, all of Central America and a great part of South America, the Caribbean and the Philippines; Britain took the whole of Australia and New Zealand, most of India, and large parts of Africa and North America; France held parts of Canada and India (nearly all of which was lost to Britain in 1763), Indochina, large parts of Africa and the Caribbean islands; the Netherlands gained the East Indies (now Indonesia) and islands in the Caribbean; Portugal obtained Brazil and several territories in Africa and Asia; and later, powers such as Germany, Belgium, Italy and Russia acquired further colonies.

This expansion helped the economy of the countries owning them. Trade flourished, because of the minor stability of the empires. By the late 16th century, American silver accounted for one-fifth of Spain's total budget.[53][54] The French colony of Saint-Domingue was one of richest European colonies in the 18th century, operating on a plantation economy fueled by slave labor. During the period of French rule, cash crops produced in Saint-Domingue comprised thirty percent of total French trade while its sugar exports represented forty percent of the Atlantic market.[55][56]

Crisis of the 17th century

The 17th century was an era of crisis.[57][58] Many historians have rejected the idea, while others promote it as an invaluable insight into the warfare, politics, economics,[59] and even art.[60] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) focused attention on the massive horrors that wars could bring to entire populations.[61] The 1640s in particular saw more state breakdowns around the world than any previous or subsequent period.[57][58] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the largest state in Europe, temporarily disappeared. In addition, there were secessions and upheavals in several parts of the Spanish empire, the world's first global empire. In Britain the entire Stuart monarchy (England, Scotland, Ireland, and its North American colonies) rebelled. Political insurgency and a spate of popular revolts seldom equalled shook the foundations of most states in Europe and Asia. More wars took place around the world in the mid-17th century than in almost any other period of recorded history. Across the Northern Hemisphere, the mid-17th century experienced almost unprecedented death rates.

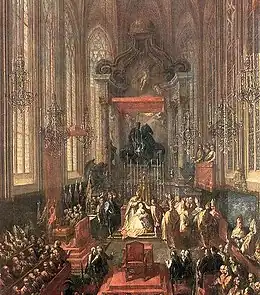

Age of absolutism

The "absolute" rule of powerful monarchs such as Louis XIV (ruled France 1643–1715),[62] Peter the Great (ruled Russia 1682–1725),[63] Maria Theresa (ruled Habsburg lands 1740–1780) and Frederick the Great (ruled Prussia 1740–86),[64] produced powerful centralized states, with strong armies and powerful bureaucracies, all under the control of the king.[65]

Throughout the early part of this period, capitalism (through mercantilism) was replacing feudalism as the principal form of economic organisation, at least in the western half of Europe. The expanding colonial frontiers resulted in a Commercial Revolution. The period is noted for the rise of modern science and the application of its findings to technological improvements, which animated the Industrial Revolution after 1750.

The Reformation had profound effects on the unity of Europe. Not only were nations divided one from another by their religious orientation, but some states were torn apart internally by religious strife, avidly fostered by their external enemies. France suffered this fate in the 16th century in the series of conflicts known as the French Wars of Religion, which ended in the triumph of the Bourbon Dynasty. England settled down under Elizabeth I to a moderate Anglicanism. Much of modern-day Germany was made up of numerous small sovereign states under the theoretical framework of the Holy Roman Empire, which was further divided along internally drawn sectarian lines. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth is notable in this time for its religious indifference and general immunity to European religious strife.

Thirty Years' War 1618–1648

The Thirty Years' War was fought between 1618 and 1648, across Germany and neighbouring areas, and involved most of the major European powers except England and Russia,[66] involving Catholics versus Protestants for the most part. The major impact of the war was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread famine and disease, and the breakup of family life, devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries, the Crown of Bohemia and northern parts of Italy, while bankrupting many of the regional powers involved. Between one-fourth and one-third of the German population perished from direct military causes or from disease and starvation, as well as postponed births.[67]

After the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the war in favour of nations deciding their own religious allegiance, absolutism became the norm of the continent, while parts of Europe experimented with constitutions foreshadowed by the English Civil War and particularly the Glorious Revolution. European military conflict did not cease, but had less disruptive effects on the lives of Europeans. In the advanced northwest, the Enlightenment gave a philosophical underpinning to the new outlook, and the continued spread of literacy, made possible by the printing press, created new secular forces in thought.

From the Union of Krewo, central and eastern Europe was dominated by Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the 16th and 17th centuries Central and Eastern Europe was an arena of conflict for domination of the continent between Sweden, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (involved in series of wars, like Khmelnytsky uprising, Russo-Polish War, the Deluge, etc.) and the Ottoman Empire. This period saw a gradual decline of these three powers which were eventually replaced by new enlightened absolutist monarchies: Russia, Prussia and Austria (the Habsburg monarchy). By the turn of the 19th century they had become new powers, having divided Poland between themselves, with Sweden and Turkey having experienced substantial territorial losses to Russia and Austria respectively as well as pauperisation.

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1715) was a major war with France opposed by a coalition of England, the Netherlands, the Habsburg monarchy, and Prussia. Duke of Marlborough commanded the English and Dutch victory at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. The main issue was whether France under King Louis XIV would take control of Spain's very extensive possessions and thereby become by far the dominant power, or be forced to share power with other major nations. After initial allied successes, the long war produced a military stalemate and ended with the Treaty of Utrecht, which was based on a balance of power in Europe. Historian Russell Weigley argues that the many wars almost never accomplished more than they cost.[68] British historian G. M. Trevelyan argues:

- That Treaty [of Utrecht], which ushered in the stable and characteristic period of Eighteenth-Century civilization, marked the end of danger to Europe from the old French monarchy, and it marked a change of no less significance to the world at large – the maritime, commercial and financial supremacy of Great Britain.[69]

Prussia

Frederick the Great, king of Prussia 1740–86, modernized the Prussian army, introduced new tactical and strategic concepts, fought mostly successful wars (Silesian Wars, Seven Years' War) and doubled the size of Prussia.[70][71]

Russia

Russia fought numerous wars to achieve rapid expansion toward the east – i.e. Siberia, Far East, south, to the Black Sea, and south-east and to central Asia. Russia boasted a large and powerful army, a very large and complex internal bureaucracy, and a splendid court that rivaled Paris and London. However the government was living far beyond its means and seized Church lands, leaving organized religion in a weak condition. Throughout the 18th century Russia remained "a poor, backward, overwhelmingly agricultural, and illiterate country."[72]

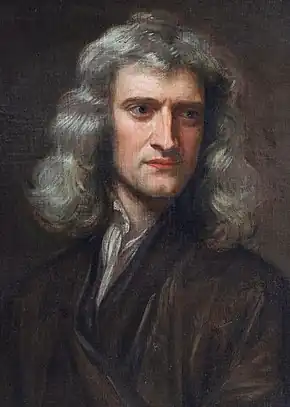

Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was a powerful, widespread cultural movement of intellectuals beginning in late 17th-century Europe emphasizing the power of reason rather than tradition; it was especially favourable to science (especially Isaac Newton's physics) and hostile to religious orthodoxy (especially of the Catholic Church).[73] It sought to analyze and reform society using reason, to challenge ideas grounded in tradition and faith, and to advance knowledge through the scientific method. It promoted scientific thought, skepticism, and intellectual interchange.[74] The Enlightenment was a revolution in human thought. This new way of thinking was that rational thought begins with clearly stated principles, uses correct logic to arrive at conclusions, tests the conclusions against evidence, and then revises the principles in light of the evidence.[74]

Enlightenment thinkers opposed superstition. Some Enlightenment thinkers collaborated with Enlightened despots, absolutist rulers who attempted to forcibly impose some of the new ideas about government into practice. The ideas of the Enlightenment exerted significant influence on the culture, politics, and governments of Europe.[75]

Originating in the 17th century, it was sparked by philosophers Francis Bacon, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, Pierre Bayle, Voltaire, Francis Hutcheson, David Hume and physicist Isaac Newton.[76] Ruling princes often endorsed and fostered these figures and even attempted to apply their ideas of government in what was known as enlightened absolutism. The Scientific Revolution is closely tied to the Enlightenment, as its discoveries overturned many traditional concepts and introduced new perspectives on nature and man's place within it. The Enlightenment flourished until about 1790–1800, at which point the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason, gave way to Romanticism, which placed a new emphasis on emotion; a Counter-Enlightenment began to increase in prominence.

In France, Enlightenment was based in the salons and culminated in the great Encyclopédie (1751–72). These new intellectual strains would spread to urban centres across Europe, notably England, Scotland, the German states, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Italy, Austria, and Spain, as well as Britain's American colonies. The political ideals of the Enlightenment influenced the American Declaration of Independence, the United States Bill of Rights, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and the Polish–Lithuanian Constitution of 3 May 1791.[77]

Norman Davies has argued that Freemasonry was a powerful force on behalf of Liberalism and Enlightenment ideas in Europe, from about 1700 to the 20th century. It expanded rapidly during the Age of Enlightenment, reaching practically every country in Europe.[78] The great enemy of Freemasonry was the Roman Catholic Church, so that in countries with a large Catholic element, such as France, Italy, Austria, Spain and Mexico, much of the ferocity of the political battles involve the confrontation between supporters of the Church versus active Masons.[79][80] 20th-century totalitarian and revolutionary movements, especially the Fascists and Communists, crushed the Freemasons.[81]

From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914)

The "long 19th century", from 1789 to 1914 saw the drastic social, political and economic changes initiated by the Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Following the reorganisation of the political map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Europe experienced the rise of Nationalism, the rise of the Russian Empire and the peak of the British Empire, as well as the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, the rise of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire initiated the course of events that culminated in the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

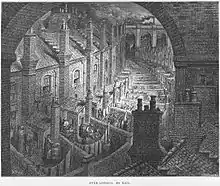

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution saw major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, and transport impacted Britain and subsequently spread to the United States and Western Europe. Technological advancements, most notably the utilization of the steam engine, were major catalysts in the industrialisation process. It started in England and Scotland in the mid-18th century with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of coal as the main fuel. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity.[82] The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world.[83]

Era of the French Revolution

Historians R.R. Palmer and Joel Colton argue:

- In 1789 France fell into revolution, and the world has never since been the same. The French Revolution was by far the most momentous upheaval of the whole revolutionary age. It replaced the "old regime" with "modern society," and at its extreme phase became very radical, so much so that all later revolutionary movements have looked back to it as a predecessor to themselves.... From the 1760s to 1848, the role of France was decisive.[84]

The era of the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic wars was a difficult time for monarchs. Tsar Paul I of Russia was assassinated; King Louis XVI of France was executed, as was his queen Marie Antoinette. Furthermore, kings Charles IV of Spain, Ferdinand VII of Spain and Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden were deposed as were ultimately the Emperor Napoleon and all of the relatives he had installed on various European thrones. King Frederick William III of Prussia and Emperor Francis II of Austria barely clung to their thrones. King George III of Great Britain lost the better part of the First British Empire.[85]

The American Revolution (1775–1783) was the first successful revolt of a colony against a European power. It rejected aristocracy and established a republican form of government that attracted worldwide attention.[86] The French Revolution (1789–1804) was a product of the same democratic forces in the Atlantic World and had an even greater impact.[87] French historian François Aulard says:

- From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life.... The French Revolution differed from other revolutions in being not merely national, for it aimed at benefiting all humanity."[88]

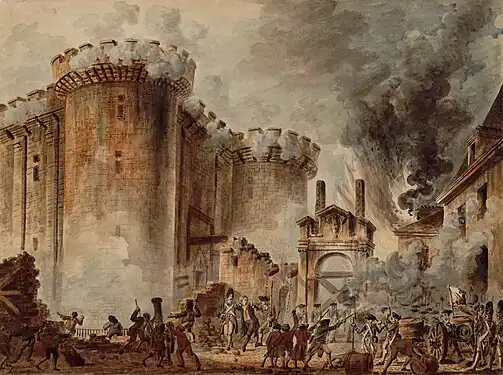

French intervention in the American Revolutionary War had nearly bankrupted the state. After repeated failed attempts at financial reform, King Louis XVI had to convene the Estates-General, a representative body of the country made up of three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. The third estate, joined by members of the other two, declared itself to be a National Assembly and created, in July, the National Constituent Assembly. At the same time the people of Paris revolted, famously storming the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789.

At the time the assembly wanted to create a constitutional monarchy, and over the following two years passed various laws including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the abolition of feudalism, and a fundamental change in the relationship between France and Rome. At first the king agreed with these changes and enjoyed reasonable popularity with the people. As anti-royalism increased along with threat of foreign invasion, the king tried to flee and join France's enemies. He was captured and on 21 January 1793, having been convicted of treason, he was guillotined.

On 20 September 1792 the National Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. Due to the emergency of war, the National Convention created the Committee of Public Safety to act as the country's executive. Under Maximilien de Robespierre, the committee initiated the Reign of Terror, during which up to 40,000 people were executed in Paris, mainly nobles and those convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal, often on the flimsiest of evidence. Internal tensions at Paris drove the Committee towards increasing assertions of radicalism and increasing suspicions. A few months into this phase, more and more prominent revolutionaries were being sent to the guillotine by Robespierre and his faction, for example Madame Roland and Georges Danton. Elsewhere in the country, counter-revolutionary insurrections were brutally suppressed. The regime was overthrown in the coup of 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794) and Robespierre was executed. The regime which followed ended the Terror and relaxed Robespierre's more extreme policies.

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte was France's most successful general in the Revolutionary wars. In 1799 on 18 Brumaire (9 November) he overthrew the government, replacing it with the Consulate, which he dominated. He gained popularity in France by restoring the Church, keeping taxes low, centralizing power in Paris, and winning glory on the battlefield. In 1804 he crowned himself Emperor. In 1805, Napoleon planned to invade Britain, but a renewed British alliance with Russia and Austria (Third Coalition), forced him to turn his attention towards the continent, while at the same time the French fleet was demolished by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar, ending any plan to invade Britain. On 2 December 1805, Napoleon defeated a numerically superior Austro-Russian army at Austerlitz, forcing Austria's withdrawal from the coalition (see Treaty of Pressburg) and dissolving the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, a Fourth Coalition was set up. On 14 October Napoleon defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, marched through Germany and defeated the Russians on 14 June 1807 at Friedland. The Treaties of Tilsit divided Europe between France and Russia and created the Duchy of Warsaw.

On 12 June 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with a Grande Armée of nearly 700,000 troops. After the measured victories at Smolensk and Borodino Napoleon occupied Moscow, only to find it burned by the retreating Russian army. He was forced to withdraw. On the march back his army was harassed by Cossacks, and suffered disease and starvation. Only 20,000 of his men survived the campaign. By 1813 the tide had begun to turn from Napoleon. Having been defeated by a seven nation army at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, he was forced to abdicate after the Six Days' Campaign and the occupation of Paris. Under the Treaty of Fontainebleau he was exiled to the island of Elba. He returned to France on 1 March 1815 (see Hundred Days), raised an army, but was finally defeated by a British and Prussian force at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815 and exiled to the small British island of Saint Helena.

Impact of the French Revolution

Roberts finds that the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, from 1793 to 1815, caused 4 million deaths (of whom 1 million were civilians); 1.4 million were French.[89]

Outside France the Revolution had a major impact. Its ideas became widespread. Roberts argues that Napoleon was responsible for key ideas of the modern world, so that, "meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on-were protected, consolidated, codified, and geographically extended by Napoleon during his 16 years of power."[90]

Furthermore, the French armies in the 1790s and 1800s directly overthrew feudal remains in much of western Europe. They liberalised property laws, ended seigneurial dues, abolished the guild of merchants and craftsmen to facilitate entrepreneurship, legalised divorce, closed the Jewish ghettos and made Jews equal to everyone else. The Inquisition ended as did the Holy Roman Empire. The power of church courts and religious authority was sharply reduced and equality under the law was proclaimed for all men.[91]

France conquered Belgium and turned it into another province of France. It conquered the Netherlands, and made it a client state. It took control of the German areas on the left bank of the Rhine River and set up a puppet Confederation of the Rhine. It conquered Switzerland and most of Italy, setting up a series of puppet states. The result was glory and an infusion of much needed money from the conquered lands. However the enemies of France, led by Britain, formed a Second Coalition in 1799 (with Britain joined by Russia, the Ottoman Empire and Austria). It scored a series of victories that rolled back French successes, and trapped the French Army in Egypt. Napoleon slipped through the British blockade in October 1799, returning to Paris, where he overthrew the government and made himself the ruler.[92][93]

Napoleon conquered most of Italy in the name of the French Revolution in 1797–99. He split up Austria's holdings and set up a series of new republics, complete with new codes of law and abolition of feudal privileges. Napoleon's Cisalpine Republic was centered on Milan; Genoa became a republic; the Roman Republic was formed as well as the small Ligurian Republic around Genoa. The Neapolitan Republic was formed around Naples, but it lasted only five months. He later formed the Kingdom of Italy, with his brother as King. In addition, France turned the Netherlands into the Batavian Republic, and Switzerland into the Helvetic Republic. All these new countries were satellites of France, and had to pay large subsidies to Paris, as well as provide military support for Napoleon's wars. Their political and administrative systems were modernized, the metric system introduced, and trade barriers reduced. Jewish ghettos were abolished. Belgium and Piedmont became integral parts of France.[94]

Most of the new nations were abolished and returned to prewar owners in 1814. However, Artz emphasizes the benefits the Italians gained from the French Revolution:

- For nearly two decades the Italians had excellent codes of law, a fair system of taxation, a better economic situation, and more religious and intellectual toleration than they had known for centuries.... Everywhere old physical, economic, and intellectual barriers had been thrown down and the Italians had begun to be aware of a common nationality.[95]

Likewise in Switzerland the long-term impact of the French Revolution has been assessed by Martin:

- It proclaimed the equality of citizens before the law, equality of languages, freedom of thought and faith; it created a Swiss citizenship, basis of our modern nationality, and the separation of powers, of which the old regime had no conception; it suppressed internal tariffs and other economic restraints; it unified weights and measures, reformed civil and penal law, authorized mixed marriages (between Catholics and Protestants), suppressed torture and improved justice; it developed education and public works.[96]

The greatest impact came in France itself. In addition to effects similar to those in Italy and Switzerland, France saw the introduction of the principle of legal equality, and the downgrading of the once powerful and rich Catholic Church. Power became centralized in Paris, with its strong bureaucracy and an army supplied by conscripting all young men. French politics were permanently polarized – new names were given, "left" and "right" for the supporters and opponents of the principles of the Revolution.

Religion

By the 19th century, governments increasingly took over traditional religious roles, paying much more attention to efficiency and uniformity than to religiosity. Secular bodies took control of education away from the churches, abolished taxes and tithes for the support of established religions, and excluded bishops from the upper houses. Secular laws increasingly regulated marriage and divorce, and maintaining birth and death registers became the duty of local officials. Although the numerous religious denominations in the United States founded many colleges and universities, that was almost exclusively a state function across Europe. Imperial powers protected Christian missionaries in African and Asian colonies.[97] In France and other largely Catholic nations, anti-clerical political movements tried to reduce the role of the Catholic Church. Likewise briefly in Germany in the 1870s there was a fierce Kulturkampf (culture war) against Catholics, but the Catholics successfully fought back. The Catholic Church concentrated more power in the papacy and fought against secularism and socialism. It sponsored devotional reforms that gained wide support among the churchgoers.[98]

Nations rising

The political development of nationalism and the push for popular sovereignty culminated with the ethnic/national revolutions of Europe. During the 19th century nationalism became one of the most significant political and social forces in history; it is typically listed among the top causes of World War I.[99][100] Most European states had become constitutional monarchies by 1871, and Germany and Italy merged many small city-states to become united nation-states. Germany in particular increasingly dominated the continent in economics and political power. Meanwhile, on a global scale, Great Britain, with its far-flung British Empire, unmatched Royal Navy, and powerful bankers, became the world's first global power. The sun never set on its territories, while an informal empire operated through British financiers, entrepreneurs, traders and engineers who established operations in many countries, and largely dominated Latin America. The British were especially famous for financing and constructing railways around the world.[101]

Napoleon's conquests of the German and Italian states around 1800–1806 played a major role in stimulating nationalism and demand for national unity.[102]

Germany

In the German states east of Prussia Napoleon abolished many of the old or medieval relics, such as dissolving the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[103] He imposed rational legal systems and his organization of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806 promoted a feeling of German nationalism. In the 1860s it was Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck who achieved German unification in 1870 after the many smaller states followed Prussia's leadership in wars against Denmark, Austria and France.[104]

Italy

Italian nationalism emerged in the 19th century and was the driving force for Italian unification or the "Risorgimento". It was the political and intellectual movement that consolidated different states of the Italian Peninsula into the single state of the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. The memory of the Risorgimento is central to both Italian nationalism and Italian historiography.[105]

Serbia

For centuries the Orthodox Christian Serbs were ruled by the Muslim-controlled Ottoman Empire. The success of the Serbian revolution (1804–1817) against Ottoman rule in 1817 marked the foundation of modern Principality of Serbia. It achieved de facto independence in 1867 and finally gained recognition in the Berlin Congress of 1878. The Serbs developed a larger vision for nationalism in Pan-Slavism and with Russian support sought to pull the other Slavs out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[106][107] Austria, with German backing, tried to crush Serbia in 1914 but Russia intervened, thus igniting the First World War in which Austria dissolved into nation states.[108]

In 1918, the region of Vojvodina proclaimed its secession from Austria-Hungary to unite with the pan-Slavic State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs; the Kingdom of Serbia joined the union on 1 December 1918, and the country was named Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It was renamed Yugoslavia, which was never able to tame the multiple nationalities and religions and it flew apart in civil war in the 1990s.

Greece

The Greek drive for independence from the Ottoman Empire inspired supporters across Christian Europe, especially in Britain. France, Russia and Britain intervened to make this nationalist dream become reality with the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829/1830).[109]

Bulgaria

Bulgarian modern nationalism emerged under Ottoman rule in the late 18th and early 19th century. An autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate was established in 1870/1872 for the diocese of Bulgaria as well as for those, wherein at least two-thirds of Orthodox Christians were willing to join it. The April Uprising in 1876 indirectly resulted in the re-establishment of Bulgaria in 1878.

Poland

In the 1790s, Germany, Russia and Austria partitioned Poland. Napoleon set up the Duchy of Warsaw, igniting a spirit of Polish nationalism. Russia took it over in 1815 as Congress Poland with the tsar as King of Poland. Large-scale nationalist revolts erupted in 1830 and 1863–64 but were harshly crushed by Russia, which tried to Russify the Polish language, culture and religion. The collapse of the Russian Empire in the First World War enabled the major powers to reestablish an independent Second Polish Republic, which survived until 1939. Meanwhile, Poles in areas controlled by Germany moved into heavy industry but their religion came under attack by Bismarck in the Kulturkampf of the 1870s. The Poles joined German Catholics in a well-organized new Centre Party, and defeated Bismarck politically. He responded by stopping the harassment and cooperating with the Centre Party.[110][111]

Spain

After the War of the Spanish Succession, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Decrees of Nova planta was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation state, through the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilians, over those of other ethnic groups, who became national minorities to be assimilated.[112][113] Since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards Catalan-speaking territories (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, part of Aragon) and other national minorities have been a historical constant.[114][115][116] The nationalization process accelerated in the 19th century, in parallel to the origin of Spanish nationalism, the social, political and ideological movement that tried to shape a Spanish national identity based on the Castilian model, in conflict with the other historical nations of the State. These nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[117][118][119][120] and still in force,[121][122][123][124] are the seed of repeated territorial conflicts within the State.

Education

An important component of nationalism was the study of the nation's heritage, emphasizing the national language and literary culture. This stimulated, and was in turn strongly supported by, the emergence of national educational systems. Latin gave way to the national language, and compulsory education, with strong support from modernizers and the media, became standard in Germany and eventually other West European nations. Voting reforms extended the franchise. Every country developed a sense of national origins – the historical accuracy was less important than the motivation toward patriotism. Universal compulsory education was extended to girls at the elementary level. By the 1890s, strong movements emerged in some countries, including France, Germany and the United States, to extend compulsory education to the secondary level.[125][126]

Ideological coalitions

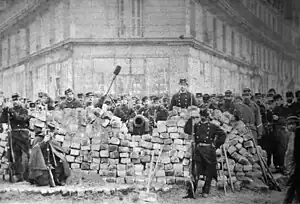

After the defeat of revolutionary France, the great powers tried to restore the situation which existed before 1789. The 1815 Congress of Vienna produced a peaceful balance of power among the European empires, known as the Metternich system. The powerbase of their support was the aristocracy.[127] However, their reactionary efforts were unable to stop the spread of revolutionary movements: the middle classes had been deeply influenced by the ideals of the French revolution, and the Industrial Revolution brought important economical and social changes.[128]

Radical intellectuals looked to the working classes for a base for socialist, communist and anarchistic ideas. Widely influential was the 1848 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[129]

The middle classes and businessmen promoted liberalism, free trade and capitalism. Aristocratic elements concentrated in government service, the military and the established churches. Nationalist movements (in Germany, Italy, Poland, Hungary, and elsewhere) sought national unification and/or liberation from foreign rule. As a result, the period between 1815 and 1871 saw a large number of revolutionary attempts and independence wars. Greece successfully revolted against Ottoman rule in the 1820s.[130]

France under Napoleon III

Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I, parlayed his famous name and to widespread popularity across France. He returned from exile in 1848, promising to stabilize the chaotic political situation.[131] He was elected president and maneuvered successfully to name himself Emperor, a move approved later by a large majority of the French electorate. The first part of his Imperial term brought many important reforms, facilitated by Napoleon's control of the lawmaking body, the government, and the French Armed Forces. Hundreds of old Republican leaders were arrested and deported. Napoleon controlled the media and censored the news. In compensation for the loss of freedom, Napoleon gave the people new hospitals and asylums, beautified and modernized Paris, and built a modern railroad and transportation system that dramatically improved commerce. The economy grew, but industrialization was not as rapid as Britain, and France depended largely on small family-oriented firms as opposed to the large companies that were emerging in the United States and Germany. France was on the winning side in the Crimean War (1854–56), but after 1858 Napoleon's foreign-policy was less and less successful. Foreign-policy blunders finally destroyed his reign in 1870–71. His empire collapsed after being defeated in the Franco-Prussian War.[132][133]