Tampere

Tampere (/ˈtæmpəreɪ/ TAM-pər-ay, US also /ˈtæmpərə, ˈtɑːmpəreɪ/ TAM-pər-ə, TAHM-pər-ay,[9][10][11] Finnish: [ˈtɑmpere] ⓘ; Swedish: Tammerfors, Finland Swedish: [tɑmːærˈforsː] ⓘ) is a city in the Pirkanmaa region, located in the western part of Finland. Tampere is the most populous inland city in the Nordic countries.[12] It has a population of 252,872; the urban area has a population of 341,696;[6] and the metropolitan area, also known as the Tampere sub-region, has a population of 414,274 in an area of 4,970 km2 (1,920 sq mi).[13] Tampere is the second largest urban area[14] and the third most populous single municipality in Finland, after the cities of Helsinki and Espoo, and the most populous Finnish city outside the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Today, Tampere is one of the most important urban, economic and cultural centres in the entire inland region.[15]

Tampere

| |

|---|---|

City | |

| Tampereen kaupunki Tammerfors stad City of Tampere | |

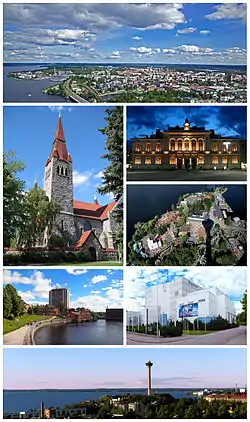

Clockwise from top: the cityscape (viewed from Näsinneula); Tampere City Hall; Särkänniemi (from Näsinneula); Tampere Hall; the skyline with Näsinneula; Tammerkoski from Hämeensilta Bridge; and the Cathedral. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Manchester of the North, Manse (in Finnish),[1] Nääsville (in Finnish),[lower-alpha 1][1] Sauna Capital of the World | |

| |

Location of Tampere in Finland | |

| Coordinates: 61°29′53″N 23°45′36″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Sub-region | Tampere |

| City rights | 1 October 1779 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor[2] | Kalervo Kummola[3] |

| Area (2018-01-01)[4] | |

| • City | 689.59 km2 (266.25 sq mi) |

| • Land | 525.03 km2 (202.72 sq mi) |

| • Water | 164.56 km2 (63.54 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 258.52 km2 (99.82 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 166th largest in Finland |

| Population (2023-09-19)[5] | |

| • City | 252,872 |

| • Rank | 3rd largest in Finland |

| • Density | 481.63/km2 (1,247.4/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 334,112[6] |

| • Urban density | 1,211.0/km2 (3,136/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 400,914 |

| Demonym(s) | tamperelainen (Finnish) tammerforsare (Swedish) Tamperean (English) |

| Population by native language | |

| • Finnish | 90.1% (official) |

| • Swedish | 0.5% |

| • Others | 9.4% |

| Population by age | |

| • 0 to 14 | 13.3% |

| • 15 to 64 | 67.5% |

| • 65 or older | 19.2% |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Website | www |

Tampere and its surroundings are part of the historic province of Satakunta. The area belonged to the province of Häme from 1831 to 1997; over time, it has often been considered a province of Tavastia. For example, in Uusi tietosanakirja, published in the 1960s, the Tampere sub-region is presented as part of the then province of Tavastia. Around the 1950s, Tampere and its surroundings began to establish themselves as a separate province of Pirkanmaa. ampere became the centre of Pirkanmaa, and Tammermaa was also used several times in the early days of the province, for example in the Suomi-käsikirja published in 1968.[16]

Tampere is wedged between two lakes, Lake Näsijärvi and Lake Pyhäjärvi,[17][18] with an 18 m (59 ft) difference in water level, and the rapids that connect them, Tammerkoski, have been an important source of power throughout history, most recently for generating electricity.[19] Tampere is known as the "Manchester of the North" because of its past as a centre of Finnish industry,[18] which has given rise to its Finnish nickname "Manse"[1] and terms such as "Manserock".[20][21][22] Tampere has also been officially declared the "Sauna Capital of the World"[18] because it has the most public saunas in the world.[12][23][24][25][26]

Helsinki is about 160 km (100 mi) south of Tampere and can be reached by Pendolino high-speed train in 1 hour 31 minutes[27] and by car in 2 hours. The distance to Turku is about the same. The Tampere–Pirkkala Airport is the eighth busiest airport in Finland, with more than 230,000 passengers using it in 2017. Tampere is also an important transit route for three Finnish highways: Highway 3 (E12), Highway 9 (E63) and Highway 12. The Tampere light rail had two lines when it started operating in 2021.[29]

Tampere is ranked 26th in the list of 446 hipster cities in the world[30] and is often rated as the most popular city in Finland.[31][32][33][18] The positive development of Tampere and the Tampere metropolitan area has continued into the 21st century, largely due to the fact that Tampere is one of the most attractive cities in Finland.[32][34][35]

Etymology

Although the name Tampere is derived from the Tammerkoski rapids (both the city and the rapids are called Tammerfors in Swedish), the origin of the Tammer- part of that name has been the subject of much debate. Ánte accepts the "straightforward" etymology of Rahkonen and Heikkilä in Proto-Samic *Tëmpël(kōškë), *tëmpël meaning "deep, slow section of a stream" and *kōškë "rapids" (cognate with the Finnish koski).[16][36][37][38] This has become the most accepted explanation in the academia, according to the Institute for the Languages of Finland.[39] Other theories include that it comes from the Swedish word damber, meaning milldam; another, that it originates from the ancient Scandinavian words þambr ("thick bellied") and þambion ("swollen belly"), possibly referring to the shape of the rapids. Another suggestion links the name to the Swedish word Kvatemberdagar, or more colloquially Tamperdagar, meaning the Ember days of the Western Christian liturgical calendar. The Finnish word for oak, tammi, also features in the speculation,[40] although Tampere is situated outside the natural distribution range of the European oak.[41]

Heraldry

The first coat of arms of Tampere was designed by Arvid von Cederwald in 1838,[42][43][44] while the current coat of arms created in 1960 and currently in use was designed by Olof Eriksson.[42] Changing the coat of arms was a controversial act, and the restoration of the old coat of arms has from time to time been demanded even after the change.[45] The new coat of arms has also been called Soviet-style in letters to the editor because of its colours.[46]

The blazon of the old coat of arms has either not survived or has never been done,[47] but the description of the current coat of arms is explained as follows: "In the red field, a corrugated counter-bar, above which is accompanied by a piled hammer, and below, a Caduceus; all gold". The colors of the coat of arms are the same as in the coat of arms of Pirkanmaa. The hammer, which looks like the first letter of the city's name T, symbolizes Tampere's early industry,[45] Caduceus its trading activities[45] and the corrugated counter-bar represents the Tammerkoski rapids, which divides Tampere's industrial and commercial areas.[48]

The city received its first seal in 1803, which depicted the city's buildings of that time and Tammerkoski.[49]

History

Early history

The earliest known permanent settlements around Tammerkoski were established in 7th century, when settlers from the west of the region started farming land in Takahuhti.[50] The area was largely inhabited by the Tavastian tribes.[51] For many centuries, the population remained low. By the 16th century, the villages of Messukylä and Takahuhti had grown to be the largest settlements in the region. Other villages nearby were Laiskola, Pyynikkälä and Hatanpää.[50] At that time, there had been a market place in the Pispala area for centuries, where the bourgeoisies from Turku in particular traded.[52] In 1638, Governor-General Per Brahe the Younger ordered that two markets be held in Tammerkoski each year, the autumn market on every Peter's Day in August and the winter market on Mati Day in February. In 1708 the market was moved from the edge of Tammerkoski to Harju and from there in 1758 to Pispala.[53]: 16 The early industries in the Pirkanmaa region in the 17th century were mainly watermills and sawmills, while in the 18th century other production began to emerge, as several small-scale ironworks, Tammerkoski distillery and Otavala spinning school were founded.[54]

Founding and industrialization

Before the founding of the city of Tampere, its neighboring municipality of Pirkkala (according to which the current Pirkanmaa region got its name) was the most administratively significant parish in the area throughout the Middle Ages.[55] This all changed in the 18th century when Erik Edner, a Finnish pastor,[56] proposed the establishment of a city of Tampere on the banks of the Tammerkoski channel in 1771–1772;[57] it was officially founded as a market place[lower-alpha 2] in 1775 by Gustav III of Sweden and four years later, 1 October 1779,[58] Tampere was granted full city rights. At this time, it was a rather small town, founded on the lands belonging to Tammerkoski manor, while its inhabitants were still mainly farmers. As farming on the city's premises was forbidden, the inhabitants began to rely on other methods of securing a livelihood, primarily trade and handicraft.[50] When Finland became part of the Russian Empire as the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1809, Tampere still had less than a thousand inhabitants.[50]

Tampere grew as a major market town and industrial centre in the 19th century;[60] the industrialization of Tampere was greatly influenced by the Finlayson textile factory, founded in 1820 by the Scottish industrialist James Finlayson.[12] By the year 1850, the factory employed around 2000 people, while the population of the city had increased to 4000 inhabitants. Other notable industrial establishments that followed Finlayson's success in the 1800s were the Tampella blast furnace, machine factory and flax mill, the Frenckell paper mill, and the Tampere broadcloth factory.[50] Tampere's population grew rapidly at the end of the 19th century, from about 7,000 in 1870 to 36,000 in 1900. At the beginning of the 20th century, Tampere was a city of workers and women, with a third of the population being factory workers and more than half women.[50] At the same time, the city's area increased almost sevenfold and impressive apartment buildings were built in the center of Tampere among modest wooden houses. The stone houses shaped Tampere in a modern direction. The construction of the sewerage and water supply network and the establishment of electric lighting were further steps towards modernisation;[50] regarding the latter, Tampere was the first Nordic city to introduce electric lights for general use in 1882.[61][62] The railway connection to Tampere from the extension of the Helsinki–Hämeenlinna line section (today part of the Main Line) via Toijala was opened to public traffic on 22 June 1876.[63]: 173

The world-famous Nokia Corporation, a multinational telecommunication company, also had its beginnings in the Tammerkoski area;[64] the company's history dates from 1865, when the Finnish-Swedish mining engineer Fredrik Idestam (1838–1916) established a pulp mill on the shores of the rapids[64] and after that, a second pulp mill was opened in 1868 near the neighboring town of Nokia, where there were better hydropower resources.[64]

Geopolitical significance

Tampere was the centre of many important political events in the early 20th century; for example, the 1905 conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), led by Vladimir Lenin, was held at the Tampere Workers' Hall, where it was decided, among other things, to launch an armed uprising, which eventually led to the October 1917 revolution in the Russian Empire.[12][65][66] Also, on 1 November 1905, during the general strike, the famous Red Declaration was proclaimed on Keskustori.[59][67] In 1918, after Finland had gained independence, Tampere played a major role, being one of the strategically important sites for the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (FSWR) during the Civil War in Finland (28 January–15 May 1918); the city was the most important industrial city in Finland at the beginning of the 20th century, marked by a huge working population.[68]: 13–14 Tampere was a Red stronghold during the war, with Hugo Salmela in command. White forces, led by General Mannerheim, captured the town after the Battle of Tampere, seizing about 10,000 Red prisoners on 6 April 1918.[69][70]

During the Winter War, Tampere was bombed by the Soviet Union several times.[71] The reason for the bombing of Tampere was that the city was an important railway junction, and also housed the State Aircraft Factory and the Tampella factory, which manufactured munitions and weapons, including grenade launchers. The most devastating bombings were on 2 March 1940, killing nine and wounding 30 city residents. In addition, ten buildings were destroyed and 30 were damaged that day.[72]

Post-war period and modern day

Prevalent in Tampere's post-World War II municipal politics was the Brothers-in-Arms Axis (aseveliakseli), which mostly consisted of the National Coalition Party and the Social Democrats. While the Centre Party was the largest political force in the Finnish countryside, it had no practical relevance in Tampere.[73]

.jpg.webp)

After World War II, Tampere was enlarged by joining some neighbouring areas. Messukylä was incorporated in 1947, Lielahti in 1950, Aitolahti in 1966 and finally Teisko in 1972. The limit of 100,000 inhabitants was crossed in Tampere in 1950.[74] Tampere was long known for its textile and metal industries, but these have been largely replaced by information technology and telecommunications during the 1990s. The technology centre Hermia in Hervanta is home to many companies in these fields.[75][76] Yleisradio started broadcasting its second television channel, Yle TV2, in Ristimäki, Tampere in 1965,[77][78] as a result of which Finland was the first of the Nordic countries to receive a second television channel, after Sweden's SVT2 started broadcasting only four years later. Tampere became a university city when the Social University moved from Helsinki to Tampere in 1960 and became the University of Tampere in 1966.[79] In 1979, Tampere-Pirkkala Airport was opened 13 km (8.1 mi) from the center of Tampere on the side of the Pirkkala municipality.[80][81]

At the turn of the 1990s, Tampere's industry underwent a major structural change, as the production of Tampella's and Tampere's textile industry in particular was heavily focused on bilateral trade with the Soviet Union, but when it collapsed in 1991 the companies lost their main customers.[19] As a result of the sudden change and the depression of the early 1990s, Finlayson and the Suomen trikoo had to reduce their operations sharply. Tampella went bankrupt.[19] But although the change left a huge amount of vacant industrial space in the city center, in the early 2000s it was gradually put to other uses, with the current Tampere cityscape being characterized above all by strong IT companies, most notably Nokia's Tampere R&D units.[82]

Geography

Tampere is part of the Pirkanmaa region and is surrounded by the municipalities of Kangasala, Lempäälä, Nokia, Orivesi, Pirkkala, Ruovesi, and Ylöjärvi.[83] There are 180 lakes that are larger than 10,000 m2 (1 ha) in Tampere, and fresh water bodies make up 24% of the city's total area.[17] The lakes have formed as separate basins from Ancylus lake approximately 7500–8000 years ago.[84] The northernmost point of Tampere is located in the Vankavesi fjard of Teisko, the southernmost at the eastern end of Lake Hervanta, the easternmost at the northeast corner of Lake Paalijärvi of Teisko and the westernmost at the southeast corner of Lake Haukijärvi near the borders of Ylöjärvi and Nokia.[85]: 11 The city center itself is surrounded by three lakes, Näsijärvi, Pyhäjärvi and much smaller Iidesjärvi. Tampere region is situated in the Kokemäki River drainage basin, which discharges into the Bothnian Sea through river which flows through Pori, the capital of Satakunta region.[84] The bedrock of Tampere consists of mica shale and migmatite,[86] and its building stone deposits are diverse: in addition to traditional granite, there is an abundance of quartz diorite, tonalite, mica shale and mica gneiss.[87] One of the most notable geographical features in Tampere is the Pyynikki Ridge (Pyynikinharju), a large esker formed from moraine during the Weichselian glaciation.[88] It rises 160 meters above sea level and is said to be the largest gravel esker in the world.[88] It is also part of Salpausselkä, a 200 km long ridge system left by the ice age.[88]

The center of Tampere (Keskusta), as well as the Pyynikki, Ylä-Pispala and Ala-Pispala districts, are located on the isthmus between Lake Pyhäjärvi and Lake Näsijärvi. The location of the city on the edge of the Tammerkoski rapids between two long waterways was one of the most important stimuli for its establishment in the 1770s.[89] The streets of central Tampere form a typical grid pattern. On the western edge of the city center, there is a north–south park street, Hämeenpuisto ("Häme Park" or "Tavastia Park"), which leads from the shore of Lake Pyhäjärvi near Lake Näsijärvi. The wide Hämeenkatu street leads east–west from the Tampere Central Station to Hämeenpuisto and crosses Tammerkoski along the Hämeensilta bridge. Also along Hämeenkatu is the longest street in the city center, Satakunnankatu, which extends from Rautatienkatu to Amuri, which crosses Tammerkoski along the Satakunnansilta bridge. The Tampere Central Square is located on the western shore of Tammerkoski, close to Hämeensilta. The traffic center of Tampere is the intersection of Itsenäisyydenkatu,[lower-alpha 3] Teiskontie, Sammonkatu, Kalevanpuisto park street, and Kaleva and Liisankallio districts.[90]

Neighbourhoods and other subdivisions

The city of Tampere is divided into seven subdivisions, each of which includes the many districts and their suburbs. There are a total of 111 statistical areas in Tampere. However, the statistical areas made for Tampere's statistics do not fully correspond to the Tampere district division or the residents' perception of the districts, as the Amuri, Kyttälä and Tammela districts, for example, are divided into two parts corresponding to the official district division, and in addition to this, Liisankallio and Kalevanrinne are often considered to belong to the Kaleva district.[91]

Climate

| Tampere | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tampere has a humid continental climate Dfb, bordering the subarctic climate (Köppen climate classification Dfc) climate zone. Winters are cold and the average temperature from December to February is below −3 °C (27 °F). Summers are cool to warm. On average, snow cover lasts 4–5 months from late November to early April. Considering it being close to the subarctic threshold and inland, winters are, on average, quite mild for the classification, as is the annual mean temperature.

| Climate data for Tampere Härmälä (TMP), elevation: 85 m (279 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1900–present (Härmälä and Tampella) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.2 (22.6) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

5.2 (41.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.3 (17.1) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.0 (−34.6) |

−36.8 (−34.2) |

−29.6 (−21.3) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−34.2 (−29.6) |

−37.0 (−34.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41 (1.6) |

30 (1.2) |

29 (1.1) |

32 (1.3) |

36 (1.4) |

66 (2.6) |

74 (2.9) |

65 (2.6) |

55 (2.2) |

57 (2.2) |

51 (2.0) |

46 (1.8) |

582 (22.9) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 32.3 (12.7) |

31.4 (12.4) |

29.5 (11.6) |

13.9 (5.5) |

1.6 (0.6) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3.3 (1.3) |

13.1 (5.2) |

27.2 (10.7) |

152.4 (60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 109 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 90 | 87 | 82 | 70 | 63 | 66 | 69 | 76 | 82 | 87 | 91 | 92 | 80 |

| Source 1: weatheronline.co.uk[92] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: FMI (precipitation, record highs and lows)[93] | |||||||||||||

Temperature records of Tampere

Temperature records of Tampere and the near-by Tampere–Pirkkala Airport:[94]

Temperature Records of Tampere

| Highest temperatures by month | |||

| Month | °C | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| June | 33.2° | 22 June 2021 | Härmälä |

| July | 33.1° | 9 July 1914 | Härmälä |

| August | 32.1° | 10 August 1912 | Härmälä |

Highest temperatures at the Tampere–Pirkkala Airport by month since 1980:[94]

| Pirkkala Airport highest temperatures by month since 1980 | |||

| Month | °C | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 8.0° | 2007 | |

| February | 9.4° | 1990 | |

| March | 14.9° | 2007 | |

| April | 24.2° | 1998 | |

| May | 29.3° | 2014 | |

| June | 31.7° | 1999 | |

| July | 32.5° | 2010 | |

| August | 31.1° | 1992 | |

| September | 24.8° | 1999 | |

| October | 17.5° | 1984 | |

| November | 12.4° | 2015 | |

| December | 10.3° | 2015 | |

Lowest temperatures in Tampere:[94]

| Lowest temperatures by month | |||

| Month | °C | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | −38.5° | 9 January 1987 | Aitoneva, Kihniö |

| February | −40.9° | 3 February 1966 | Mouhijärvi |

Lowest temperatures at the Tampere–Pirkkala Airport by month since 1980:[94]

| Pirkkala Airport lowest temperatures by month since 1980 | |||

| Month | °C | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | −35.8° | 1987 | |

| February | −31.8° | 2007 | |

| March | −29.1° | 1981 | |

| April | −14.8° | 1988 | |

| May | −7.2° | 1999 | |

| June | −3.0° | 1984 | |

| July | 1.5° | 1987 | |

| August | −0.4° | 1984 | |

| September | −7.0° | 1986 | |

| October | −16.4° | 1992 | |

| November | −22.0° | 1990 | |

| December | −33.0° | 1995 | |

Cityscape

Revival and nationalism

Tampere has buildings from many architectural periods. Only the old stone church of Messukylä represents medieval building culture.[95] Early 19th century neoclassicism, in turn, is represented by the Tampere Old Church and its belfry. The Gothic Revival buildings in Tampere that emerged from neoclassicism are the new Messukylä Church and the Alexander Church, and the Renaissance Revival buildings are the Hatanpää Manor, the Tampere City Hall,[59] the Ruuskanen House and Näsilinna. The romantic nationalism design can be seen in the Commerce House, the Tirkkonen House, the Palander House, the Tampere Cathedral, the Tampere Central Fire Station and the National Bank Building in Tampere.[91] At an early stage, the use of red brick as a material in the industrial buildings along Tammerkoski, such as the Finlayson and Tampella factories, has left a strong imaginary mark on the city.[96][97]

Functionalism and modernism

Post-Art Nouveau classicism was largely Nordic,[98] during which the Laikku Culture House, Hotel Tammer, the Tuulensuu House and the Viinikka Church were built in Tampere. After functionalism became the prevailing style in the 1930s, the Tampere Central Station, the Tempo House, a bus station and the Kauppi Hospital were built in Tampere. There is no single accepted designation for the post-war style, but the key representatives of the reconstruction period are the Bank of Finland House, the Amurinlinna House and the Pyynikki Swimming Hall. The rationalist buildings of the modernist period are represented by the University of Tampere, the Tampere Central Hospital, Sampola, the School of Economics, Ratina Stadium and the Kaleva Church.[98] After this, diverse modernism will be represented by, among others, the Metso Main Library, the Hervanta Operations Center, the Tampere Hall, the university extension and Nokia's office building in Hatanpää.[91]

The city center of Tampere and also its western parts have been developed in a more modern direction since the 2010s,[99] and the city aims to get the center to take on its future form by the 2030s.[100] Plans have been drawn up for the Central Station area in particular in the form of the "Tampere Deck" project, in connection with which a new multi-purpose arena and high-rise buildings have been sent to the area.[101][102] A light rail network has also been recently built in the downtown area. Artificial island projects are planned on the shores of the lakes, which would create new residential areas for several thousand inhabitants.[102] The projects are estimated to cost several billion euros.[100][101][102]

Economy

The Tampere region, Pirkanmaa, which includes outlying municipalities, has around 509,000 residents,[104] 244,000 employed people,[105] and a turnover of 28 billion euros as of 2014.[106]

According to the Tampere International Business Office, the area is strong in mechanical engineering and automation, information and communication technologies, and health and biotechnology, as well as pulp and paper industry education. Unemployment rate was 15.7% in August 2020.[107] 70% of the areas jobs are in the service sector. Less than 20% are in the manufacturing sector. 34.5% of employed people live outside the Tampere municipality and commute to Tampere for work. Meanwhile, 15.6% of Tampere's residents work outside Tampere.[85] In 2014 the largest employers were Kesko, Pirkanmaan Osuuskauppa, Alma Media and Posti Group.[108]

According to a study carried out by the Synergos Research and Training Center of the University of Tampere, the total impact of tourism in the Tampere region in 2012 was more than 909 million euros. Tourism also brought 4,805 person-years to the region.[109] The biggest single attraction in Tampere is the Särkänniemi amusement park, which had about 630,000 visitors in 2016.[110] In addition, in 2015, 1,021,151 overnight stays were made in Tampere hotels. The number exceeded the previous record year with more than 20,000 overnight stays. All that makes Tampere the second most popular city in Finland after Helsinki in terms of hotel stays. Leisure tourism accounted for 55,4% of overnight stays and occupational tourism for 43,2%. The occupancy rate of all accommodation establishments with more than 20 rooms was 57,0%, while that of accommodation establishments in the whole country was 48,3%.[111]

Tampere's economic profit in 2015 was the worst of big Finnish cities.[112] In 2016 the loss of the fiscal year was 18,8 million euros.[113] In the city's economy, the largest revenues come from taxes and government contributions. In 2015, the city received 761 million euros in municipal tax revenue. In addition, 61,4 million euros came from corporate taxes and 64 million euros from property taxes.[114] Tax revenues have not increased as expected in the 2010s, although the city's population has increased. This has been affected by high unemployment.[115]

Tampere is headquarters for Bronto Skylift, an aerial rescue and aerial work platform manufacturer.[116]

Energy

In 2013, Tampereen Energiantuotanto, which is part of the Tampereen Sähkölaitos Group, generated 1,254 GWh of electricity and 2,184 GWh of district heating. The two units of the Naistenlahti's power plant generated a total of about 65% and the Lielahti's power plant about 30% of the electricity production. In district heating production, the Naistenlahti power plant units accounted for 57% and the Lielahti power plant for 23%. Tampere's ten heating centers accounted for 21%.[85]: 44

In 2013, the share of natural gas in energy production was about 65%. Wood and peat accounted for about 17%. In addition, hydropower and oil were used.[85]: 44 Emissions from energy production have decreased in the 21st century due to the growth of renewable forms of production and the modernization of the Naistenlahti plant. In 2013, approximately 669,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions and 297 tonnes of sulfur dioxide emissions were generated.[85]: 46–47

Water and waste management

66,5% of Tampere's domestic water is surface water and 33,5% groundwater. 58% of the water was diverted to economic use and 13% to industrial use. In addition to Tampere, Tampereen Vesi manages water in Pirkkala. Almost all surface water comes from Lake Roine. In addition, Tampereen Vesi has four surface water plants in Lake Näsijärvi and five groundwater intakes.[85]: 68–69 Tampereen Vesi is 96% responsible for the wastewater of Tampere, Kangasala, Pirkkala and Ylöjärvi. In 2012, a total of 31,9 million cubic meters of wastewater was treated in Tampere. The Viinikanlahti treatment plant treats more than 75% of wastewater.[85]: 85

Pirkanmaan Jätehuolto handles waste management in Tampere. It has waste treatment facilities in Nokia's Lake Koukkujärvi and Tampere's Lake Tarastenjärvi.[85]: 92

Demographics

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1815 | 793 | — |

| 1840 | 1,819 | +129.4% |

| 1850 | 3,207 | +76.3% |

| 1860 | 5,232 | +63.1% |

| 1870 | 6,986 | +33.5% |

| 1880 | 13,645 | +95.3% |

| 1890 | 20,132 | +47.5% |

| 1900 | 36,344 | +80.5% |

| 1910 | 45,442 | +25.0% |

| 1920 | 47,830 | +5.3% |

| 1930 | 50,138 | +4.8% |

| 1939 | 78,012 | +55.6% |

| 1972 | 163,609 | +109.7% |

| Source: Tilastollinen päätoimisto,[117] Statistics Finland[118] | ||

The city of Tampere has 252,872 inhabitants, making it the 3rd most populous municipality in Finland and the tenth in the Nordics. The Tampere region, with 414,274 people, is the second largest after the Helsinki region. Tampere is home to 5% of Finland's population. 9.5% of the population has a foreign background, which is above the national average. However, it is lower than in the major Finnish cities of Helsinki, Espoo, Vantaa or Turku.[118]

The demographic structure of Tampere shows that the city is a very popular place to study, as the number of young adults is significantly higher than in other municipalities in the region. At the end of 2012, the old-age dependency ratio was 45. Approximately 17.3% of the population was over the age of 65.[85]: 13 Just over half of the population is female, as in the country as a whole. The population is fairly well educated, with two-thirds of those over 15 having completed post-primary education.[119]

At the end of 2018, there were a total of 140,039 dwellings in Tampere, of which 127,639 were permanently occupied and 12,400 were not permanently occupied.[120] Of these, 74% were apartment buildings, 14% were detached houses, 10% were terraced houses, and 2% were other residential buildings. Between 2002 and 2020, more than 40,000 new dwellings will be completed in Tampere.[121] Living space has been growing for a long time, although after 2008 growth came to a virtual standstill. The average living space at the end of 2012 was about 36.8 m2 per inhabitant, compared with about 19.2 m2 in 1970 and about 31.8 m2 in 1990. The average dwelling had about 1.8 inhabitants in 2012.[85]: 13

For more than ten years, Tampere has been one of the most migratory municipalities, as more than 1,930 new residents moved to Tampere in January–September 2021. Nokia, Kangasala and Lempäälä, which are among Tampere's neighbouring municipalities, have also been identified as the most migratory municipalities, rising to the list of the 20 most attractive municipalities.[34][35] Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, Tampere has become Finland's most attractive area for internal migration, as Tampere gained the most migration gains in 2020.[122]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 166,228 |

| 1985 | 169,026 |

| 1990 | 172,560 |

| 1995 | 182,742 |

| 2000 | 195,468 |

| 2005 | 204,337 |

| 2010 | 213,217 |

| 2015 | 225,118 |

| 2020 | 238,420 |

Languages

Population by mother tongue (2022)[118]

Tampere is the largest monolingual municipality in Finland. The majority of the population - 224,266 people or 90.1% - speak Finnish as their first language. In Tampere, 1,333 people, or 0.5% of the population, speak Swedish. This is the second largest number of Swedish speakers in monolingual Finnish-speaking municipalities after Kaarina. Kaarina and Tampere are also the only monolingual Finnish-speaking municipalities with a separate Swedish-speaking community. In 1900, Swedish speakers made up more than six per cent of Tampere's population, and less than two per cent in 1950.[123]

As English and Swedish are compulsory school subjects, functional bilingualism or trilingualism acquired through language studies is not uncommon. At least 160 different languages are spoken in Tampere. The most widely spoken foreign languages are Russian (1.4%), Arabic (1.0%), Farsi (0.8%) and English (0.7%).[118]

Immigration

| Population by country of birth (2022)[118] | ||

| Nationality | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| 226,644 | 91.0 | |

| 2,197 | 0.9 | |

| 1,252 | 0.5 | |

| 1,182 | 0.5 | |

| 1,181 | 0.5 | |

| 1,090 | 0.4 | |

| 873 | 0.4 | |

| 870 | 0.3 | |

| 846 | 0.3 | |

| 833 | 0.3 | |

| 564 | 0.2 | |

In 2022, there were 23,561 people with a migrant background living in Tampere, or 9.5% of the population.[note 1] There were 22,365 residents who were born abroad, or 9% of the population. The number of foreign citizens in Tampere was 14,758.[125] Most foreign-born citizens came from the former Soviet Union, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sweden, and Estonia.[118]

The relative share of immigrants in the population of Tampere is slightly above the national average.[118] Tampere attracts more migration from within Finland than directly from abroad. Nevertheless, the city's new residents are increasingly of foreign origin. This will increase the proportion of foreign residents in the coming years.

Urban areas

In 2019, out of the total population of 238,140, 231,648 people lived in urban areas and 3,132 in sparsely populated areas, while the coordinates of 3,360 people were unknown. This made Tampere's degree of urbanization 98.7%.[126] The urban population in the municipality was divided between three statistical urban areas as follows:[127]

| # | Urban area | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tampere urban area | 225,440 |

| 2 | Vuores | 5,316 |

| 3 | Kämmenniemi | 892 |

Religion

In 2022, the Evangelical Lutheran Church was the largest religious group with 58% of the population of Tampere. Other religious groups accounted for 3.2% of the population. 38.8% of the population had no religious affiliation.[118]

Education

The comprehensive education is given mainly in Finnish but the city has special bilingual groups where students study in Finnish and a second language (English, French or German).[128] Furthermore, there is a private Swedish-speaking school in the Kaakinmaa district (Swedish Svenska samskolan i Tammerfors) that covers all levels of education from preschool to high school.[129]

.jpg.webp)

There are three institutions of higher education in the Tampere area totaling 40,000 students: the university and two polytechnic institutions (Finnish: ammattikorkeakoulu). Tampere University (TUNI) has over 20,000 students and is located in two campuses, one in the Kalevanharju district, close to the city centre, and one in Hervanta, in the southern part of the city. The institution was formed in 2019 as a result of the merge of University of Tampere (UTA) and Tampere University of Technology (TUT). TUNI is also the major shareholder of the Tampere University of Applied Sciences (Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu, TAMK), a polytechnic counting about 10,000 students.[130] The Police University College, the polytechnic institution serving all of Finland in its field of specialization, is also located in Tampere.[131][132]

Tampere University Hospital (Tampereen yliopistollinen sairaala, TAYS) in the Kauppi district, one of the main hospitals in Finland, is affiliated with Tampere University. It is a teaching hospital with 34 medical specializations.

The Nurmi district in the northern part of city also houses the Tampere Christian School (Tampereen kristillinen koulu), which operates on a co-Christian basis and is maintained by the Adventist Church of Finland, offering free basic education based on Christian basic values and outlook on life for all grades of primary school.[133]

Arts and culture

.jpg.webp)

Tampere is known for its active cultural life. Some of the most popular writers in Finland, such as Väinö Linna, Kalle Päätalo, and Hannu Salama, hail from Tampere. These authors are known particularly as writers depicting the lives of working-class people, thanks to their respective backgrounds as members of the working class. Also from such a background was the poet Lauri Viita of the Pispala district, which was also the original home of the aforementioned Hannu Salama. On 1 October, Tampere celebrates the annual Tampere Day (Finnish: Tampereen päivä), which hosts a variety of public events.[134][91]

Media

Tampere is a strong media city, as the television center in Tohloppi and Ristimäki districts has had a nationwide Yle TV2 television channel since the 1970s,[91] and Finnish radio, for example, began in Tampere when Arvi Hauvonen founded the first broadcasting station in 1923.[91] Yle TV2 has its roots in Tamvisio, which was transferred to Yleisradio in 1964. Kakkoskanava ("Channel 2") has been a major influence in Tampere, and several well-known television programs and series have been shot in the city,[91] such as TV comedies Tankki täyteen, Reinikainen and Kummeli. The Ruutu+ streaming service's popular crime drama television series Lakeside Murders (Finnish: Koskinen), based on the Koskinen book series by Seppo Jokinen, is also produced and filmed in Tampere.[135][136]

The Tampere Film Festival, an annual international short film event, is held every March.[137] Tampere has also served as a filming location for international film productions, most notably the 1993 British comedy film The Big Freeze[138] and the 2022 American sci-fi film Dual.[139][140]

In 2014, Aamulehti, which was published in Tampere and was founded in 1881,[141][142] was the third largest newspaper in Finland in terms of circulation, after Helsingin Sanomat and Ilta-Sanomat. The circulation of the magazine was 106,842 (2014).[143] In addition, a free city newspaper Tamperelainen (literally translated "Tamperean", meaning person who live in Tampere) will be published in the city.[91] In November 2016, the Tamperelainen was awarded the second best city newspaper in Finland.[144]

The city is also known as the home of the popular Hydraulic Press Channel on YouTube, which originates from a machine shop owned by Lauri Vuohensilta.[145]

Food

A local food speciality is mustamakkara, which resembles the black pudding of northern England. It is a black sausage made by mixing pork, pig's blood and crushed rye and flour and is stuffed into the intestines of an animal. It is commonly eaten with lingonberry sauce. Especially Tammelantori square in the district of Tammela is known for its mustamakkara kiosks.[147]

A newer Tampere tradition are munkki, fresh sugary doughnuts that are sold in several cafés around Tampere, but most traditionally in Pyynikki observation tower.[148]

One of the specialties of Tampere's local barbecue dishes include the peremech (Finnish: pärämätsi) based on traditional Tatar food. It is a pie reminiscent of Karelian pasty with seasoned ground meat inside.[149][150]

In the 1980s, in addition to mustamakkara and barley bread, the old parish dish of Tampere was also called a potato soup, home-made small beer (kotikalja), a sweetened lingonberry porridge and a sweetened potato casserole (Imelletty perunalaatikko).[151]

Since 1991, the two-day fish market event (Tampereen kalamarkkinat) in Laukontori attracts as many as 80,000–100,000 visitors in year, and is held both in the spring on vappu and in the autumn on Tampere Day.[152][153]

Music

.JPG.webp)

Tampere is home to the Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra (Tampere Filharmonia), which is one of only two full-sized symphony orchestras in Finland; the other one is located in Helsinki. The orchestra's home venue is the Tampere Hall,[12] and their concerts include classical, popular, and film music. Tampere Music Festivals organises three international music events: The Tampere Jazz Happening each November, and in alternate years The Tampere Vocal Music Festival and the Tampere Biennale. Professional education in many fields of classical music, including performing arts, pedagogic arts, and composition, is provided by Tampere University of Applied Sciences and Tampere Conservatoire.

Tammerfest, Tampere's urban rock festival, is held every July.[154] The Blockfest, which also takes place in Tampere during the summer months,[154] is the largest hip hop event in the Nordic countries.[155] The Tampere Floral Festival is an annual event, held each Summer.

Manserock became a general term for rock music from Tampere, which was essentially rock music with Finnish lyrics. Manserock was especially popular during the 1970s and 1980s, and its most popular artists included Juice Leskinen, Virtanen, Kaseva, Popeda, and Eppu Normaali. In 1977, Poko Rekords, the first record company in Tampere, was founded.[156]

In the 2010s, there has been a lot of popular musical activity in Tampere, particularly in the fields of rock and heavy/black metal; one of the most important metal music events in Tampere is the Sauna Open Air Metal Festival.[157] Some of the most popular bands based in Tampere include Negative, Uniklubi, and Lovex. Tampere also has an active electronic music scene. Tampere hosts an annual World of Tango Festival (Maailmantango),[158] which is one of the most significant tango events in Finland next to the Tangomarkkinat of Seinäjoki.

Theatre

Tampere has a lengthy tradition of theater, with established institutions such as Tampereen Työväen Teatteri, Tampereen Teatteri, and Pyynikin Kesäteatteri, which is an open-air theatre with the oldest revolving auditorium in Europe. The longest-running directors of the Tampereen Teatteri include Eino Salmelainen and Rauli Lehtonen, and the Tampereen Työväen Teatteri has Kosti Elo, Eino Salmelainen and Lasse Pöysti.[91] The Tampere Theatre Festival (Tampereen teatterikesä) is an international theatre festival held in the city each August. Tampere also has the Tampere Opera, founded in 1946.[159]

Tampere's other professional theaters are Teatteri Siperia; restaurant theater Teatteripalatsi; Teatteri Telakka, known for its artistic experiments; Ahaa Teatteri, which specializes in children's and young people's plays; puppet theater Teatteri Mukamas, and Tanssiteatteri MD, specializes in contemporary dance performances.[160] In addition, there are also three cinemas in Tampere: two Finnkino's theaters, Cine Atlas and Plevna,[161][162] and private Arthouse Cinema Niagara,[163] which serves as the main venue for the Cinemadrome Festival, which presents horror, action, sci-fi, trash, and other cult films.[164] Local cinemas also included the historic Imatra, formerly located in the Kyttälä district, which was completely destroyed on a fire in the midst of a 1924 film Wages of Virtue on 23 October 1927, killing 21 people.[165]

Religious activities

As is the case with most of the rest of Finland, most Tampere citizens belong to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. One Lutheran church in Tampere is Finlayson Church in the district by the same name. Tampere also has a variety of other religious services spanning from traditional to charismatic. There are also some English speaking services, such as the Tampere English Service, an international community affiliated with the Tampere Pentecostal Church (Tampereen helluntaiseurakunta).[166][167] English services of the International Congregation of Christ the King (ICCK) are organized by the Anglican Church in Finland and the Lutheran Parishes of Tampere. The Catholic parish of the Holy Cross[168] also offers services in Finnish, Polish and English. Other churches may also have English speaking ministries. Tampere is the center of a LDS stake (diocese). Other churches in Tampere are the Baptist Church, the Evangelical Free Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland, the Finnish Orthodox Church and the Nokia Revival.

There was an organized Jewish community until 1981. Though a small number of Jews remain in Tampere, organized communal life ended at that time.[169]

There are three registered Muslim communities in Tampere. The biggest of them being Tampere Islam Society with over 1500 members.[170]

City rivalry with Turku

Tampere ostensibly has a long-standing mutual feud with the city of Turku,[171] the first capital of Finland, and they tend to compete for the title of being the "second grand city of Finland" after Helsinki.[172][173] This rivalry is largely expressed in jokes in one city about the other; prominent targets are the traditional Tampere food, mustamakkara, the state of the Aura River in Turku, and the regional accents. Tampere is well known as a food destination because of its food culture. Since 1997, students at Tampere have made annual excursions to Turku to jump on the market square, doing their part to undo the post-glacial rebound and push the city back into the Baltic Sea.[174][175]

Main sights

One of the main tourist attractions is the Särkänniemi amusement park, which includes the landmark Näsinneula tower, topped by a revolving restaurant. In addition to these, it used to house a dolphinarium. Other sites of interest are Tampere Cathedral, Tampere City Hall, Tampere Central Library Metso ("Capercaillie"), Kaleva Church (both designed by Reima Pietilä), the Tampere Hall (along Hämeenkatu) for conferences and concerts, the Tampere Market Hall and historical Pyynikki observation tower.[18]

Tampere has at least seven hotels, the most noteworthy of which are Hotel Tammer, Hotel Ilves, and Hotel Torni, the tallest hotel building in Finland.[103] The Holiday Club Tampere spa is also located in the Lapinniemi district on the shores of Lake Näsijärvi.[176] There are also many significant shopping centers in the city center of Tampere and its suburbs; the most notable shopping centers are Ratina, Koskikeskus, DUO, Like, and Tullintori.

Tampere is also home to one of the last museums in the world dedicated to Vladimir Lenin. The museum is housed in the Tampere Workers' Hall (along Hallituskatu) where during a subsequent Bolshevik conference in the city, Lenin met Joseph Stalin for the first time.[12][177][178] Lenin moved to Tampere in August 1905, but eventually fled for Sweden in November 1907 when being pursued by the Russian Okhrana. Lenin would not return to any part of the Russian Empire until ten years later, when he heard of the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

There are many museums and galleries, including:

- The Vapriikki Museum Centre[179][18] which includes the Natural History Museum of Tampere, Finnish Hockey Hall of Fame, Finnish Museum of Games, Post Museum and the Shoe Museum

- Hatanpää Manor and Hatanpää Arboretum

- The Näsilinna Palace

- Tampere Art Museum[180]

- Tampere Lenin Museum

- The Moomin Museum,[12][181][18] about Moomins

- Rupriikki Media Museum

- Spy Museum in Siperia[182]

- Workers' housing museum in Amuri.[183]

- Finland's largest glass sculpture, owned by the City of Tampere, "Pack Ice / The Mirror of the Sea" by the renowned artist Timo Sarpaneva, was installed in the entrance lobby of the downtown shopping mall KoskiKeskus until it was moved to a warehouse.[184]

Pispala

Pispala is a ridge located between the two lakes. It is divided into Ylä-Pispala ("Upper Pispala") and Ala-Pispala ("Lower Pispala"). It's the highest gravel ridge in the world, raising 80 m (260 ft) above Lake Pyhäjärvi and around 160 m (520 ft) above sea level. It was used to house the majority of industrial labour in the late 19th and early 20th century, when it was part of Suur-Pirkkala and its successor Pohjois-Pirkkala. It was a free area to be built upon by the working-class people working in Tampere factories. It joined Tampere in 1937. Currently it is a residential area undergoing significant redevelopment and together with neighbouring Pyynikki it forms an important historical area of Tampere.[12]

Events

Sports

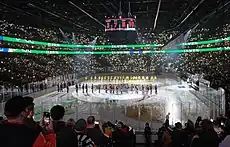

Tampere's sporting scene is mainly driven by ice hockey.[185] The first Finnish ice hockey match was played in Tampere, on the ice of Pyhäjärvi. Tampere is nicknamed the hometown of Finnish ice hockey. Three exceptional ice hockey teams come from Tampere: Tappara, Ilves and KOOVEE. Especially both Tappara and Ilves have had a great impact on Finnish ice hockey culture and are among the most successful teams in Finland;[185][186] of these, Ilves was the first Tampere-based hockey team to win the 1935-1936 Finnish championship.[185] The Finnish ice hockey museum, and the first ice hockey arena to be built in Finland, the Hakametsä arena, are both located in Tampere.[102] Construction of a new main ice hockey arena, Tampere Deck Arena,[187] began in 2018, and was first opened to the public on 3 December 2021, although the official opening date was on 15 December.[188][189][190][191] The name of the new arena was supposed to be UROS LIVE,[192] but due to the financial difficulties of the sponsor behind it, the name was abandoned.[193] After that, Nokia Corporation was chosen as the new sponsor on 19 November 2021, and the arena was renamed as Nokia Arena.[194] The arena served one of two host cities for both the 2022 IIHF World Championship and the 2023 IIHF World Championship.[185][195][196][197]

Like ice hockey, association football is also a popular sport in Tampere. Ilves, the professional football club of Tampere,[198] alone has over 4,000 players in its football teams, while Tampere boasts over 100 (mostly junior) football teams. Basketball is another popular sport in Tampere; the city has three basketball teams with big junior activity and one of them, Tampereen Pyrintö,[199][200] plays on the highest level (Korisliiga) and was the Finnish Champion in 2010, 2011, and 2014.[201]

Tampere Saints is the American football club in the city, that won division 2 in 2015 and plays in the Maple League (division 1) in summer 2017.[202] Tampere has a baseball and softball club, the Tampere Tigers, which plays in the top division of Finnish baseball.[203][204] In addition to all of the above, volleyball, wrestling and boxing are also among Tampere's best-known sports.[91]

Tampere hosted some of the preliminaries for the 1952 Summer Olympics, the 1965 World Ice Hockey Championships[185][205] and was co-host of the EuroBasket 1967. The city also hosted two canoe sprint world championships, in 1973 and 1983. In 1977, Tampere hosted the World Rowing Junior Championships and in 1995 the Senior World Rowing Championships. Recently, Tampere was the host of the 10th European Youth Olympic Festival on 17–25 July 2009[206] and the 2010 World Ringette Championships on 1–6 November at Hakametsä arena.

Tampere hosted the 2023 European Masters Games from 26 June to 9 July.[207]

In Basketball, the Nokia Arena will host the EuroBasket 2025 as one of the host cities.

Concerts

Ratina Stadium of Tampere, in the district by the same name, has served as the venue for many of the most significant concerts, most notably in connection with the Endless Forms Most Beautiful World Tour in 2015 by the band Nightwish.[208][209] Other noteworthy tours from other bands held at Ratina Stadium include Iron Maiden (Somewhere Back in Time World Tour, 2008), Bruce Springsteen (Working on a Dream Tour, 2009), AC/DC (Black Ice World Tour, 2010), Red Hot Chili Peppers (I'm with You World Tour, 2012), Bon Jovi (Because We Can World Tour, 2013), Robbie Williams (The Heavy Entertainment Show Tour, 2017) and Rammstein (Rammstein Stadium Tour, 2019).

Transport

Tampere is an important railroad hub in Finland and there are direct railroad connections to, for example, Helsinki, Turku and the Port of Turku, Oulu, Jyväskylä, and Pori. Every day about 150 trains with an annual total of 8 million passengers arrive and depart in the Tampere Central Railway Station, which is located in the city center.[210] There are also frequent bus connections to destinations around Finland. To the south of Tampere, there is the Tampere Ring Road, which is important for car traffic and which is part of Finnish highways number 3 (on the west side) and number 9 (on the east side). The main stretch of the ring road sees over 50,000 vehicles per day,[211] and, according to the ELY Centre of Pirkanmaa, the western part of the ring road is the busiest road in Finland, if highway and ring road connections in the Helsinki metropolitan area are excluded.[212] There are also plans for another ring road project that would run from Pirkkala to Tampere's Hervanta and possibly in the future to Kangasala.[213] Teiskontie, which runs east of the city center, is part of Highway 12 in the direction of Lahti. This highway also runs through the center of Tampere under the name Paasikiven–Kekkosentie,[53]: 75, 77 below the downtown as the Tampere Tunnel, which is the longest road tunnel built in Finland for car traffic.[214]

Tampere is served by Tampere–Pirkkala Airport, located in neighboring municipality Pirkkala some 13 km (8 mi) southwest of the city, and it replaced the former Härmälä Airport, which was closed in 1979.[81] The current airport is connected to the city centre of Tampere by bus route 103, and to that of Pirkkala by bus route 39.

The public transport network in Tampere currently consists of a bus network and two lines of city's light rail, operating from 9 August 2021.[216] The Tampere Bus Station, designed by Jaakko Laaksovirta and Bertel Strömmer, representing functionalist architecture, was completed in 1938,[217][218]: 203–204 being the largest bus station in the Nordic countries at the time,[219] and between 1948 and 1976, the city also had an extensive trolleybus network, which was also the largest trolleybus system in Finland.[220] As of 2017, commuter rail service on the railroad lines connecting Tampere to the neighbouring towns of Nokia and Lempäälä is being established.[221]

In 2015, the Port of Tampere,[222] the charter port area carrying passengers on the shores of Lake Näsijärvi and Lake Pyhäjärvi,[223] was the busiest inland waterway in Finland in terms of the number of passengers (71,750).[224] A partial explanation for the high number of passengers can be found in the summer traffic to the Viikinsaari island in Lake Pyhäjärvi, where people travel for an excursion or various cultural events such as watching a summer theater.[225] Domestic passenger and connecting vessel traffic was only busier in the Finnish sea area in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, between mainland Finland and Åland in the Archipelago Sea.[224]

In the 2010s, Tampere has made efforts to invest in the smooth running of cycling and walkability.[226] Thanks to it, the city was awarded the title of "Cycling Municipality of the Year" in 2013.[227] According to a survey conducted in 2015, the attractiveness of both cycling and walking had increased during 2014 and 2015.[228] In any case, during the 21st century, the growth of bicycle traffic has been clearly faster than the growth of the city's population, and the number of cycles has increased by an average of about 2% per year.[229]

Distances to other cities

- Helsinki – 180 km (110 mi)

- Hämeenlinna – 79 km (49 mi)

- Joensuu – 396 km (246 mi)

- Jyväskylä – 150 km (93 mi)

- Kuopio – 297 km (185 mi)

- Lahti – 130 km (81 mi)

- Lappeenranta – 276 km (171 mi)

- Oulu – 490 km (300 mi)

- Pori – 110 km (68 mi)

- Seinäjoki – 177 km (110 mi)

- Turku – 163 km (101 mi)

- Vaasa – 240 km (150 mi)

Government

In 2007, Tampere switched to a new model of government. Since then, a mayor and four deputy mayors have been chosen for a period of four years by the city council. The mayor also becomes the seat of the city council for the duration of the tenure.

Tampere was the first Finnish municipality to be elected mayor.[230] However, the mayor does not have an official relationship with the municipality; the mayor serves as chairman of the city board and directs the municipality's activities, and the mayor's duties are defined in the city government's bylaws.[230] Because the mayor and deputy mayors are trustees, they can be removed by the council if they lose the majority trust.[91]

For the first two years, Timo P. Nieminen, representing the National Coalition Party from 2007 to 2012, served as mayor. In 2013, Anna-Kaisa Ikonen of the same party was elected mayor.[230] As of 1 June 2017, the number of deputy mayors decreased from four to three.[231] Lauri Lyly (SDP) was elected Mayor of the City of Tampere for the period 2017–2021 at the City Council meeting on 12 June 2017.[230]

Mayors over time

- Kaarle Nordlund 1929–1943

- Sulo Typpö 1943–1957

- Erkki Lindfors 1957–1969

- Pekka Paavola 1969–1985

- Jarmo Rantanen 1985–2007

- Timo P. Nieminen (kok.) 2007–2012

- Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (kok.) 2013–2017

- Lauri Lyly (sd.) 2017–2021

- Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (kok.) 2021–2023

- Kalervo Kummola (kok.) 2023–present

Notable people

Born before 1900

.jpg.webp)

- Emil Aaltonen (1869—1949), industrialist and philanthropist

- Emanuel Aromaa (1873—1933), politician

- Eero Berg (1898–1969), long-distance runner and Olympic gold medalist

- Minna Canth (1844–1897), author and social activist

- Rosa Clay (1875–1959), a Namibian-born Finnish American teacher, singer and choral conductor

- Minna Craucher (1891–1932), socialite and spy

- James Finlayson (1772–1852), Scottish Quaker and industrialist

- Väinö Hakkila (1882–1958), politician

- Gustaf Idman (1885–1961), diplomat and a non-partisan Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Alma Jokinen (1882–1939), politician

- Feliks Kellosalmi (1877–1939), politician

- Augusta Laine (1867–1949), teacher of home economics and politician

- Frans Oskar Lilius (1871–1928), politician

- Wivi Lönn (1872–1966), architect

- Kaapo Murros (1875–1951), journalist, lawyer, writer and politician

- Juho Kusti Paasikivi (1870–1956), the Prime Minister of Finland and the 7th President of Finland

- Aaro Pajari (1897–1949), Major General and the Knight of the Mannerheim Cross

- Arvo Pohjannoro (1893–1963), Lutheran clergyman and politician

- Anders Rajala (1891–1957), wrestler

- Julius Saaristo (1891–1969) track and field athlete and Olympic gold medalist

- Matti Schreck (1897–1946), banker and film producer

- Frans Eemil Sillanpää (1888–1964), author and Nobel laureate

- Bertel Strömmer (1890–1962), architect

- Vilho Tuulos (1895–1967), triple jumper, long jumper and Olympic gold medalist

- August Wesley (1887–?), journalist, trade unionist and revolutionary

Born after 1900

.jpg.webp)

- Jonne Aaron (born 1983), singer

- Sinikka Antila (born 1960), lawyer and diplomat

- Aleksander Barkov (born 1995), Finnish-Russian professional ice hockey player

- Anu Bradford (born 1975), Finnish-American author and law professor

- Johanna Debreczeni (born 1980), singer

- Henrik Otto Donner (1939–2013), composer and music personality

- Anna Falchi (born 1972), Finnish-Italian model and film actress

- Mauri Favén (1920–2006), painter

- Jussi Halla-aho (born 1971), politician and former leader of the Finns Party

- Roope Hintz (born 1996), professional ice hockey player

- Anja Ignatius (1911–1995), violinist and music educator

- Seppo Jokinen (born 1949), author

- Viljo Kajava (1909–1998), author and poet

- Tapani Kalliomäki (born 1970), stage and film actor

- Glen Kamara (born 1995), professional footballer

- Jorma Karhunen (1913–2002), Finnish Air Force ace and the Knight of the Mannerheim Cross

- Leo Kinnunen (1943–2017), Formula One driver

- Urpo Lahtinen (1931–1994), journalist and magazine publisher, founder of Tamperelainen

- Kimmo Leinonen (born 1949), ice hockey executive and writer[232]

- Mika Koivuniemi (born 1967), bowling coach and professional ten-pin bowler

- Kiira Korpi (born 1988), figure skater

- Patrik Laine (born 1998), professional ice hockey player

- Väinö Linna (1920–1992), author

- Jyrki Lumme (born 1966), professional hockey player

- Tiina Lymi (born 1971), actress, director, screenwriter and author

- Taru Mäkelä (born 1959), film director and screenwriter

- Eeva-Liisa Manner (1921–1995), poet, playwright and translator

- Sanna Marin (born 1985), politician, current leader of the Social Democratic Party and former Prime Minister of Finland (2019–2023)

- Sakari Mattila (born 1989), professional footballer

- Matthau Mikojan (born 1982), rock musician, singer, guitarist and songwriter

- Pate Mustajärvi (born 1956), rock singer

- Mikko Nousiainen (born 1975), actor

- Teppo Numminen (born 1968), professional ice hockey player

- Luka Nurmi (born 2004), racing driver

- Erno Paasilinna (1935–2000), author and journalist

- Pekka Paavola (born 1933), politician and Minister of Justice

- Tero Palmroth (born 1953), racing driver

- Oiva Paloheimo (1910–1973), author, poet and aphorist

- Veijo Pasanen (1930–1988), actor

- Aku Pellinen (born 1993), racing driver

- Sakari Puisto (born 1976), politician

- Raisa Räisänen (1983–?), still missing 16-year-old girl, who was declared dead in absentia in 2007

- Matti Ranin (1926–2013), actor

- Leo Riuttu (1913–1989), actor

- Seela Sella (born 1936), actress

- Heikki Silvennoinen (born 1954), musician and actor

- Kikka (1964–2005), pop and schlager singer

- Jukka Tapanimäki (1961–2000), software developer and game programmer

- Armi Toivanen (born 1980), actress

- Jussi Välimäki (born 1974), rally driver

- Lauri Viita (1916–1965), poet

- Sofia Vikman (born 1983), politician

- Olavi Virta (1915–1972), singer

- Juuso Walli (born 1996), professional ice hockey player[233]

- Hans Wind (1919–1995), fighter pilot, flying ace and the Knight of the Mannerheim Cross

- Aki Yli-Salomäki (born 1972), composer, music critic and music journalist

International relations

Tampere is twinned with:

- Chemnitz, Germany[234]

- Essen, Germany[235]

- Kaunas, Lithuania[234]

- Kyiv, Ukraine[234]

- Klaksvík, Faroe Islands[234]

- Kópavogur, Iceland[234]

- Linz, Austria[234]

- Łódź, Poland (since 1996)[236]

- Miskolc, Hungary[234]

- Norrköping, Sweden[234]

- Odense, Denmark[234]

- Olomouc, Czech Republic[234]

- Brașov, Romania[234]

- Tartu, Estonia[234]

- Trondheim, Norway (since 1946)[237]

- Guangzhou, China[238][239]

- Syracuse, United States[240]

Tampere has two additional "friendship cities":

See also

Notes

- Statistics Finland classifies a person as having a "foreign background" if both parents or the only known parent were born abroad.[124]

- Pronounced in almost the same way as Nashville

- Known in Sweden as köping and the Finnish word kauppala.

- Formerly known as Puolimatkankatu

References

- Lindfors, Jukka. "Tampere on Manse ja Nääsville". YLE (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Finland: Tampere". TheMayor.eu. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "Kalervo Kummolaa esitetään odotetusti Tampereen pormestariksi". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- "Area of Finnish Municipalities 1.1.2018" (PDF). National Land Survey of Finland. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Finland's preliminary population figure was 5,587,841 at the end of August 2023". StatFin. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- "Taajamat väkiluvun ja väestöntiheyden mukaan 31 December 2017" (in Finnish). Statistics Finland.

- "Demographic Structure by area as of 31 December 2022". Statistics Finland's PX-Web databases. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- "Population according to age (1-year) and sex by area and the regional division of each statistical reference year, 2003–2020". StatFin. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- "Tampere". lexico.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- "Tampere". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Green, Allison (25 July 2019). "21 Cool Things to Do in Tampere, Finland". Eternal Arrival. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Facts and figures". tampereenseutu.fi. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018.

- "A dynamic city of growth – Tampere is the second largest urban centre in Finland". 13 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Isomäki, Aarno. "Tampereen tarina" (PDF) (in Finnish). City of Tampere.

- Heikkilä, Mikko (2012). "Etymologinen tapaus Tammerkoski". Sananjalka (in Finnish). 54: 50–75. doi:10.30673/sja.86714.

- "Vesiensuojelu" (in Finnish). City of Tampere. 15 October 2015. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021.

- Hodges, Michael (29 January 2023). "The fairytale Finnish city you've probably never heard of". The Times. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- Kortelainen, Kari (8 December 2019). "Suomen Manchesterin sydän on voimaa tuottanut Tammerkoski - alueen menestynein yritys oli Ruotsin vallan aikana valtion viinanpolttimo". Tekniikka & Talous (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere in brief" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- "The Economy in the Tampere Region" (PDF). Tampere International Business Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2008.

- katko, Tapio S.; Juuti, Petri S. "Watering the city of Tampere" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- "Tampere is the Sauna Capital of the World". 16 March 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Finnish Sauna Society and International Sauna Association: "Tampere is the Sauna Capital"". 22 May 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere – the sauna capital of the world". 7 February 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere – the Sauna Capital of the World ~ Sauna from Finland". 25 February 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Now Finland is even faster - VR". www.vr.fi. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018.

- "Tampere light rail network opens under budget and ahead of schedule pelastaudutaan". International Railway Journal. 21 August 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- "World's most hipster cities revealed: Tampere ranked number 26!". Visit Tampere. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020.

- "Tampere rated Finland's most popular city". YLE. 26 March 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Finland: Tampere". Eurocities. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- "Ratikan verran rakastettavampi! Listasimme 14 syytä, joiden vuoksi Tampere on aivan ykkösmesta" [Why is Tampere so popular? Here's 14 reasons!]. Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). 15 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Vuorimäki, Tiina (4 May 2021). "Tampere Suomen ylivoimainen ykkönen muuttovoitossa alkuvuonna – pääkaupunkiseudun vetovoima romahtanut: "Se on tosi iso muutos"". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- Kalliosaari, Kati (23 October 2021). "Tampereen vetovoima on ihan omaa luokkaansa, Helsinki putosi jumbosijalle – "En olisi tällaista tilannetta uskonut näkeväni"". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- Ánte, Luobbal Sámmol Sámmol (2012). "An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory". A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Vol. 266. pp. 63–117.

- Heikkilä, Mikko (2012). "Tampere–saamelaisen Tammerkosken kaupunki". Virittäjä (in Finnish). 1.

- Rahkonen, Pauli (2011). "Tampere–saamelainen koskiappellatiivi". Virittäjä (in Finnish). 2.

- "Mistä tulee nimi Tampere?". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Kumpu, Ville (19 November 2003). "Tampere ei avaudu tutkijoille". Utain – Tampereen yliopiston toimittajakoulutuksen viikkolehti (in Finnish). University of Tampere. Archived from the original on 26 March 2005.

- "Metsätammi (Quercus robur)". luomus.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampereen vaakunat". City of Tampere (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- Kotivuori, Yrjö (2005). "Ylioppilasmatrikkeli 1640–1852: Arvid von Cederwald". University of Helsinki (in Finnish).

- "Tampereen vaakunat" (in Finnish). City of Tampere. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019.

- "38 § Erkki Axénin ja Peter Löfbergin ym. valtuustoaloite vanhan Arvid von Cedervallin suunnitteleman vaakunan käyttöönottamiseksi" (in Finnish). City of Tampere. 17 January 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008.

- "Aamulehti: Kumpi Tampereen vaakunoista on parempi?" (in Finnish). Aamulehti. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- Willberg, Leena (1987). Pirkanmaan kuntien tunnukset (in Finnish). Tampereen kaupungin museot, Pirkanmaan maakuntamuseo. ISBN 951-9430-21-0.

- "Usein kysyttyä" (in Finnish). City of Tampere. 4 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- Iltanen, Jussi (2013). Suomen kuntavaakunat (in Finnish). Karttakeskus. p. 88.

- Lind, Mari (2015). Tampereen tarina (PDF) (in Finnish). ISBN 978-951-609-783-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016.

- "Pirkanmaa kulttuurialueena" (PDF) (in Finnish). Pirkan Kylät ry. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Sinisalo, Uuno (1947). "Tampereen kirja". Tampere-Seuran Julkaisuja (in Finnish). Tampere-Seura. ISSN 0356-987X.

- Maija Louhivaara (1999). Tampereen kadunnimet (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampereen museot. ISBN 951-609-105-9.

- "Teollistumisen varhaisvaiheet". Pirkanmaa (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2020.

- Rasila, Viljo (1985). Pirkanmaan synty (in Finnish). Tampereen historiallinen seura. pp. 6–25.

- Kotivuori, Yrjö (2005). "Ylioppilasmatrikkeli 1640–1852: Erik Edner". University of Helsinki (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Uola, Mikko (1978). Mitä Missä Milloin 1979 (in Finnish). Otava. p. 198. ISBN 951-1-04873-2.

- "The City Of Tampere – Tampere in brief – History". Archived from the original on 28 December 2009.

- "Tampere City Hall". spottinghistory.com. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Symington, Andy; Dunford, George (2009). Finland. Lonely Planet. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-1-74104-771-4. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Kautonen, Mika (18 November 2015). "A history of continuous change and innovation". Smart Tampere Ecosystem. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Pohjoismaiden ensimmäinen sähkövalo syttyi Tampereella 1882, eikä moni ollut uskoa silmiään". Tekniikka&Talous (in Finnish). 7 December 2021.

- Suolahti, Gunnar W. (1936). Suomen kulttuurihistoria 4 (in Finnish). Gummerus.

- Tikkanen, Johanna (22 November 2013). "Nokian juuret ovat Tammerkosken rannalla". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Palonen, Osmo. "Lenin ja Stalin kohtaavat - myyttejä ja historiaa". uta.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

- Brackman, Roman (2001). The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780714650500.

- Kaunonen, Gary (2010). Challenge Accepted: A Finnish Immigrant Response to Industrial America in Michigan's Copper Country. MSU Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-62895-154-7. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Voionmaa, Väinö (1929). Tampereen historia 2 (in Finnish). City of Tampere.

- Tepora, Tuomas; Roselius, Aapo, eds. (14 August 2014). The Finnish Civil War 1918: History, Memory, Legacy. Brill Publishers. p. 100. ISBN 978-90-04-28071-7. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Norum, Roger (1 June 2010). The Rough Guide to Finland. Rough Guides. p. 438. ISBN 978-1-84836-969-6. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Lammi, Esko (1990). Talvisodan Tampere (in Finnish). Häijää Invest. ISBN 9789529017072.

- Juonala, Jouko (2019). "Ilmahälytys!". Talvisota: Ilta-Sanomien erikoislehti (in Finnish). Sanoma Media Finland Oy.

- Ekman, Marianne; Gustavsen, Björn; Asheim, Bjorn Terje; Pålshaugen, Öyvind (2010). Learning Regional Innovation: Scandinavian Models. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 174. ISBN 9780230304154. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Lind, Mari; Antila, Kimmo; Liuttunen, Antti (2011). Tammerkoski ja kosken kaupunki (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampereen museot. ISBN 9789516094949.

- "Vapaat toimitilat Hermia". Technopolis (in Finnish). 9 September 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Toimitilat Tampereen". MatchOffice (in Finnish). Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- Iikka Taavitsainen. Television musiikkiohjelmat vuosina 1958–1972. Televisio määrällisenä musiikkisivistäjänä (in Finnish). Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. p. 60.

- "Tesvision joutsenlaulu". YLE (in Finnish). 21 November 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Kaataja, Sampsa. "Korkeakoululaitos saapuu Tampereelle". Koskesta voimaa (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere-Pirkkala: tärkeä kenttä, loistava sijainti". Business Tampere (in Finnish). 6 September 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Repo, Toni (17 May 2018). "Pääsy kielletty: Tältä näyttää Tampere-Pirkkalan lennonjohtotornissa – 156 askelmaa johdattaa ainutlaatuisen maiseman äärelle". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Nokia-kännyköiden tutkimuskeskus Tampereelle". Uusi Teknologia (in Finnish). 2 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Paikkatietoikkuna". Paikkatietoikkuna.fi (in Finnish). maanmittauslaitos.fi. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Palomäki, Risto. Tampereen kaupungin alueella sijaitsevien järvien kehitys ja niiden vedenlaatu 1990-2005 (PDF) (in Finnish). Sanna Junttanen, Heli Ylinen. ISBN 978-951-609-320-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2019.

- Ympäristön tila Tampereella 2014 (in Finnish). Tampere: City of Tampere. 2015. ISBN 978-951-609-755-1.

- Kähkönen, Yrjö (2009). "Tampereen alueen kallioperä" (PDF). GTK (in Finnish). Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "Tampereen maaperä". Tampereen seudun taajamageologinen kartoitus- ja kehittämishanke (TAATA) (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Pyynikki". www.tampere.fi (in Finnish). 28 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020.

- R. Hautamäki (2015). Tampereen tarina (in Finnish). ISBN 978-951-609-783-4.

- "Kaupungin maantieteellinen asema EUREF-FIN-koordinaattijärjestelmässä" (in Finnish). City of Tampere. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- Niemelä, Jari (2008). Tamperelaisen tiedon portaat (in Finnish). Tampere-seura. ISBN 978-952-5558-05-0.

- "weatheronline.uk". weatheronline.co.uk. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "FMI open data". Finnish Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere, Härmälä keskilämpötilat 1961-" (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Lukijalta: Pyhä Mikko on Tampereen vanhin rakennus, mutta se jää yllättävän vähälle huomiolle". Aamulehti (in Finnish). 9 January 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Punatiilinen perintö" (in Finnish). Visit Tampere. 2018. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022.

- "Tulli Halls by Schauman & Nordgren Architects + MASU Planning and Schauman Arkkitehdit wins competition in the old customs area in Tampere – Aasarchitecture". 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021.

- Kauta, Jasmina; Keinänen, Milja; Pietiläinen, Olli (7 June 2019). "Kaupungin kasvot". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "City of Tampere: an International Ideas Competition in a Magnificent Finnish Lakeside City". Business Wire. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Tampere is the city of growth and development". Business Tampere. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- Jäntti, Mari (23 February 2021). "Tampere jatkaa keskustan rajua uudistamista miljardihankkeella – katso, miltä rautatieaseman seutu näyttää 15 vuoden kuluttua". YLE (in Finnish). Retrieved 25 July 2022.