History of France

The first written records for the history of France appeared in the Iron Age. What is now France made up the bulk of the region known to the Romans as Gaul. Greek writers noted the presence of three main ethno-linguistic groups in the area: the Gauls, the Aquitani, and the Belgae. The Gauls, the largest and best attested group, were Celtic people speaking what is known as the Gaulish language. Over the course of the first millennium BC the Greeks, Romans and Carthaginians established colonies on the Mediterranean coast and the offshore islands. The Roman Republic annexed southern Gaul as the province of Gallia Narbonensis in the late 2nd century BC, and Roman Legions under Julius Caesar conquered the rest of Gaul in the Gallic Wars of 58–51 BC. Afterwards a Gallo-Roman culture emerged and Gaul was increasingly integrated into the Roman Empire.

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

In the later stages of the Roman Empire, Gaul was subject to barbarian raids and migration, most importantly by the Germanic Franks. The Frankish king Clovis I united most of Gaul under his rule in the late 5th century, setting the stage for Frankish dominance in the region for hundreds of years. Frankish power reached its fullest extent under Charlemagne. The medieval Kingdom of France emerged from the western part of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, known as West Francia, and achieved increasing prominence under the rule of the House of Capet, founded by Hugh Capet in 987.

A succession crisis following the death of the last direct Capetian monarch in 1328 led to the series of conflicts known as the Hundred Years' War between the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet. The war formally began in 1337 following Philip VI's attempt to seize the Duchy of Aquitaine from its hereditary holder, Edward III of England, the Plantagenet claimant to the French throne. Despite early Plantagenet victories, including the capture and ransom of John II of France, fortunes turned in favor of the Valois later in the war. Among the notable figures of the war was Joan of Arc, a French peasant girl who led French forces against the English, establishing herself as a national heroine. The war ended with a Valois victory in 1453.

Victory in the Hundred Years' War had the effect of strengthening French nationalism and vastly increasing the power and reach of the French monarchy. During the Ancien Régime period over the next centuries, France transformed into a centralized absolute monarchy through Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. At the height of the French Wars of Religion, France became embroiled in another succession crisis, as the last Valois king, Henry III, fought against rival factions the House of Bourbon and the House of Guise. Henry, the Bourbon King of Navarre, won the conflict and established the Bourbon dynasty. A burgeoning worldwide colonial empire was established in the 16th century. The French monarchy's political power reached a zenith under the rule of Louis XIV, "The Sun King".

In the late 18th century the monarchy and associated institutions were overthrown in the French Revolution. The country was governed for a period as a Republic, until Napoleon Bonaparte's French Empire was declared. Following his defeat in the Napoleonic Wars, France went through several further regime changes, being ruled as a monarchy, then briefly as a Second Republic, and then as a Second Empire, until a more lasting French Third Republic was established in 1870.

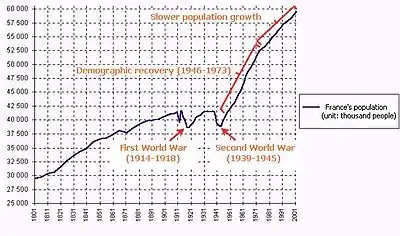

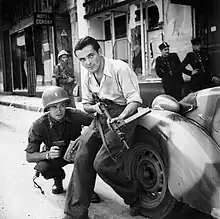

France was one of the Triple Entente powers in World War I against Germany and the Central Powers. France was one of the Allied Powers in World War II, but was conquered by Nazi Germany in 1940. The Third Republic was dismantled, and most of the country was controlled directly by Germany while the south was controlled until 1942 by the collaborationist Vichy government. Living conditions were harsh as Germany drained away food and manpower, and many Jews were killed. The Free France movement took over the colonial empire, and coordinated the wartime Resistance. Following liberation in 1944, the Fourth Republic was established. France slowly recovered, and enjoyed a baby boom that reversed its very low fertility rate. Long wars in Indochina and Algeria drained French resources and ended in political defeat. In the wake of the 1958 Algerian Crisis, Charles de Gaulle set up the French Fifth Republic. Into the 1960s decolonization saw most of the French colonial empire become independent, while smaller parts were incorporated into the French state as overseas departments and collectivities. Since World War II France has been a permanent member in the UN Security Council and NATO. It played a central role in the unification process after 1945 that led to the European Union. Despite slow economic growth in recent years, it remains a strong economic, cultural, military and political factor in the 21st century.

Prehistory

Stone tools discovered at Chilhac (1968) and Lézignan-la-Cèbe in 2009 indicate that pre-human ancestors may have been present in France at least 1.6 million years ago.[1] Neanderthals were present in Europe from about 400,000 BC,[2] but died out about 40,000 years ago, possibly out-competed by the modern humans during a period of cold weather. The earliest modern humans — Homo sapiens — entered Europe by 43,000 years ago (the Upper Palaeolithic).[3]

The Paleolithic cave paintings of Gargas (c. 25,000 BC) and Lascaux (c. 15,000 BC) as well as the Neolithic-era Carnac stones (c. 4500 BC) are among the many remains of local prehistoric activity in the region. In the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age the territory of France was largely dominated by the Bell Beaker culture, followed by the Armorican Tumulus culture, Rhône culture, Tumulus culture, Urnfield culture and Atlantic Bronze Age culture, among others. The Iron Age saw the development of the Hallstatt culture followed by the La Tène culture, the final cultural stage prior to Roman expansion across Gaul. The first written records for the history of France appear in the Iron Age. What is now France made up the bulk of the region known to the Romans as Gaul. Roman writers noted the presence of three main ethno-linguistic groups in the area: the Gauls, the Aquitani, and the Belgae. The Gauls, the largest and best attested group, were Celtic people speaking what is known as the Gaulish language.

Over the course of the 1st millennium BC the Greeks, Romans, and Carthaginians established colonies on the Mediterranean coast and the offshore islands. The Roman Republic annexed southern Gaul as the province of Gallia Narbonensis in the late 2nd century BC, and Roman forces under Julius Caesar conquered the rest of Gaul in the Gallic Wars of 58–51 BC. Afterwards a Gallo-Roman culture emerged and Gaul was increasingly integrated into the Roman empire.

Ancient history

Greek colonies

In 600 BC, Ionian Greeks from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (present-day Marseille) on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, making it one of the oldest cities in France.[4][5] At the same time, some Celtic tribes arrived in the eastern parts (Germania superior) of the current territory of France, but this occupation spread in the rest of France only between the 5th and 3rd century BC.[6]

Gaul

Covering large parts of modern-day France, Belgium, northwest Germany and northern Italy, Gaul was inhabited by many Celtic and Belgae tribes whom the Romans referred to as Gauls and who spoke the Gaulish language roughly between the Oise and the Garonne (Gallia Celtica), according to Julius Caesar. On the lower Garonne the people spoke Aquitanian, a Pre-Indo-European language related to (or a direct ancestor of) Basque whereas a Belgian language was spoken north of Lutecia but north of the Loire according to other authors like Strabo. The Celts founded cities such as Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris) and Burdigala (Bordeaux) while the Aquitanians founded Tolosa (Toulouse).

Long before any Roman settlements, Greek navigators settled in what would become Provence.[7] The Phoceans founded important cities such as Massalia (Marseille) and Nikaia (Nice),[8] bringing them into conflict with the neighboring Celts and Ligurians. Some Phocean great navigators, such as Pytheas, were born in Marseille. The Celts themselves often fought with Aquitanians and Germans, and a Gaulish war band led by Brennus invaded Rome c. 393 or 388 BC following the Battle of the Allia.

However, the tribal society of the Gauls did not change fast enough for the centralized Roman state, who would learn to counter them. The Gaulish tribal confederacies were then defeated by the Romans in battles such as Sentinum and Telamon during the 3rd century BC. In the early 3rd century BC, some Belgae (Germani cisrhenani) conquered the surrounding territories of the Somme in northern Gaul after battles supposedly against the Armoricani (Gauls) near Ribemont-sur-Ancre and Gournay-sur-Aronde, where sanctuaries were found.

When Carthaginian commander Hannibal Barca fought the Romans, he recruited several Gaulish mercenaries who fought on his side at Cannae. It was this Gaulish participation that caused Provence to be annexed in 122 BC by the Roman Republic.[9] Later, the Consul of Gaul — Julius Caesar — conquered all of Gaul. Despite Gaulish opposition led by Vercingetorix, the Gauls succumbed to the Roman onslaught. The Gauls had some success at first at Gergovia, but were ultimately defeated at Alesia in 52 BC. The Romans founded cities such as Lugdunum (Lyon), Narbonensis (Narbonne) and allow in a correspondence between Lucius Munatius Plancus and Cicero to formalize the existence of Cularo (Grenoble).[10]

Roman Gaul

Gaul was divided into several different provinces. The Romans displaced populations to prevent local identities from becoming a threat to Roman control. Thus, many Celts were displaced in Aquitania or were enslaved and moved out of Gaul. There was a strong cultural evolution in Gaul under the Roman Empire, the most obvious one being the replacement of the Gaulish language by Vulgar Latin. It has been argued the similarities between the Gaulish and Latin languages favoured the transition. Gaul remained under Roman control for centuries and Celtic culture was then gradually replaced by Gallo-Roman culture.

The Gauls became better integrated with the Empire with the passage of time. For instance, generals Marcus Antonius Primus and Gnaeus Julius Agricola were both born in Gaul, as were emperors Claudius and Caracalla. Emperor Antoninus Pius also came from a Gaulish family. In the decade following Valerian's capture by the Persians in 260, Postumus established a short-lived Gallic Empire, which included the Iberian Peninsula and Britannia, in addition to Gaul itself. Germanic tribes, the Franks and the Alamanni, entered Gaul at this time. The Gallic Empire ended with Emperor Aurelian's victory at Châlons in 274.

A migration of Celts occurred in the 4th century in Armorica. They were led by the legendary king Conan Meriadoc and came from Britain. They spoke the now extinct British language, which evolved into the Breton, Cornish, and Welsh languages.

In 418 the Aquitanian province was given to the Goths in exchange for their support against the Vandals. Those same Goths had sacked Rome in 410 and established a capital in Toulouse.

The Roman Empire had difficulty responding to all the barbarian raids, and Flavius Aëtius had to use these tribes against each other in order to maintain some Roman control. He first used the Huns against the Burgundians, and these mercenaries destroyed Worms, killed king Gunther, and pushed the Burgundians westward. The Burgundians were resettled by Aëtius near Lugdunum in 443. The Huns, united by Attila, became a greater threat, and Aëtius used the Visigoths against the Huns. The conflict climaxed in 451 at the Battle of Châlons, in which the Romans and Goths defeated Attila.

The Roman Empire was on the verge of collapsing. Aquitania was definitely abandoned to the Visigoths, who would soon conquer a significant part of southern Gaul as well as most of the Iberian Peninsula. The Burgundians claimed their own kingdom, and northern Gaul was practically abandoned to the Franks. Aside from the Germanic peoples, the Vascones entered Wasconia from the Pyrenees and the Bretons formed three kingdoms in Armorica: Domnonia, Cornouaille and Broërec.[11]

Frankish kingdoms (486–987)

In 486, Clovis I, leader of the Salian Franks, defeated Syagrius at Soissons and subsequently united most of northern and central Gaul under his rule. Clovis then recorded a succession of victories against other Germanic tribes such as the Alamanni at Tolbiac. In 496, pagan Clovis adopted Catholicism. This gave him greater legitimacy and power over his Christian subjects and granted him clerical support against the Arian Visigoths. He defeated Alaric II at Vouillé in 507 and annexed Aquitaine, and thus Toulouse, into his Frankish kingdom.[12]

The Goths retired to Toledo in what would become Spain. Clovis made Paris his capital and established the Merovingian dynasty but his kingdom would not survive his death in 511. Under Frankish inheritance traditions, all sons inherit part of the land, so four kingdoms emerged: centered on Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims. Over time, the borders and numbers of Frankish kingdoms were fluid and changed frequently. Also during this time, the Mayors of the Palace, originally the chief advisor to the kings, would become the real power in the Frankish lands; the Merovingian kings themselves would be reduced to little more than figureheads.[12]

By this time Muslims had conquered Hispania and Septimania became part of the Al-Andalus, which were threatening the Frankish kingdoms. Duke Odo the Great defeated a major invading force at Toulouse in 721 but failed to repel a raiding party in 732. The mayor of the palace, Charles Martel, defeated that raiding party at the Battle of Tours and earned respect and power within the Frankish Kingdom. The assumption of the crown in 751 by Pepin the Short (son of Charles Martel) established the Carolingian dynasty as the kings of the Franks.

Carolingian power reached its fullest extent under Pepin's son, Charlemagne. In 771, Charlemagne reunited the Frankish domains after a further period of division, subsequently conquering the Lombards under Desiderius in what is now northern Italy (774), incorporating Bavaria (788) into his realm, defeating the Avars of the Danubian plain (796), advancing the frontier with Al-Andalus as far south as Barcelona (801), and subjugating Lower Saxony after a prolonged campaign (804).

In recognition of his successes and his political support for the papacy, Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Romans, or Roman Emperor in the West, by Pope Leo III in 800. Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious (emperor 814–840) kept the empire united; however, this Carolingian Empire would not survive Louis I's death. Two of his sons — Charles the Bald and Louis the German — swore allegiance to each other against their brother — Lothair I — in the Oaths of Strasbourg, and the empire was divided among Louis's three sons (Treaty of Verdun, 843). After a last brief reunification (884–887), the imperial title ceased to be held in the western realm, which was to form the basis of the future French kingdom. The eastern realm, which would become Germany, elected the Saxon dynasty of Henry the Fowler.[13]

Under the Carolingians, the kingdom was ravaged by Viking raiders. In this struggle some important figures such as Count Odo of Paris and his brother King Robert rose to fame and became kings. This emerging dynasty, whose members were called the Robertines, were the predecessors of the Capetian dynasty. Led by Rollo, some Vikings had settled in Normandy and were granted the land, first as counts and then as dukes, by King Charles the Simple, in order to protect the land from other raiders. The people that emerged from the interactions between the new Viking aristocracy and the already mixed Franks and Gallo-Romans became known as the Normans.[14]

State building into the Kingdom of France (987–1453)

Kings

- Capetian dynasty (House of Capet):

- Hugh Capet, 940–996

- Robert the Pious, 996–1027

- Henry I, 1027–1060

- Philip I, 1060–1108

- Louis VI the Fat, 1108–1137

- Louis VII the Young, 1137–1180

- Philip II Augustus, 1180–1223

- Louis VIII the Lion, 1223–1226

- Saint Louis IX, 1226–1270

- Philip III the Bold, 1270–1285

- Philip IV the Fair, 1285–1314

- Louis X the Quarreller, 1314–1316

- John I the Posthumous, 1316

- Philip V the Tall, 1316–1322

- Charles IV the Fair, 1322–1328

- House of Valois:

- Philip VI of Valois, 1328–1350

- John II the Good, 1350–1364

- Charles V the Wise, 1364–1380

- Charles VI the Mad, 1380–1422

- Disputed English interlude (between Charles VI and VII), 1422:

- Henry V of England

- Henry VI of England and France

- Disputed English interlude (between Charles VI and VII), 1422:

- Charles VII the Well Served, 1422–1461

Strong princes

France was a very decentralised state during the Middle Ages. The authority of the king was more religious than administrative. The 11th century in France marked the apogee of princely power at the expense of the king when states like Normandy, Flanders or Languedoc enjoyed a local authority comparable to kingdoms in all but name. The Capetians, as they were descended from the Robertians, were formerly powerful princes themselves who had successfully unseated the weak and unfortunate Carolingian kings.[15] The Capetians, in a way, held a dual status of King and Prince; as king they held the Crown of Charlemagne and as Count of Paris they held their personal fiefdom, best known as Île-de-France.[15]

Some of the king's vassals would grow sufficiently powerful that they would become some of the strongest rulers of western Europe. The Normans, the Plantagenets, the Lusignans, the Hautevilles, the Ramnulfids, and the House of Toulouse successfully carved lands outside France for themselves. The most important of these conquests for French history was the Norman Conquest by William the Conqueror.[16]

An important part of the French aristocracy also involved itself in the crusades, and French knights founded and ruled the Crusader states.

Rise of the monarchy

The monarchy overcame the powerful barons over ensuing centuries, and established absolute sovereignty over France in the 16th century.[17] Hugh Capet in 987 became "King of the Franks" (Rex Francorum). He was recorded to be recognised king by the Gauls, Bretons, Danes, Aquitanians, Goths, Spanish and Gascons.[18]

Hugh's son—Robert the Pious—was crowned King of the Franks before Capet's demise. Hugh Capet decided so in order to have his succession secured. Robert II, as King of the Franks, met Emperor Henry II in 1023 on the borderline. They agreed to end all claims over each other's realm, setting a new stage of Capetian and Ottonian relationships. The reign of Robert II was quite important because it involved the Peace and Truce of God (beginning in 989) and the Cluniac Reforms.[18]

.jpg.webp)

Under King Philip I, the kingdom enjoyed a modest recovery during his extraordinarily long reign (1060–1108). His reign also saw the launch of the First Crusade to regain the Holy Land.

It is from Louis VI (reigned 1108–37) onward that royal authority became more accepted. Louis VI was more a soldier and warmongering king than a scholar. The way the king raised money from his vassals made him quite unpopular; he was described as greedy and ambitious. His regular attacks on his vassals, although damaging the royal image, reinforced the royal power. From 1127 onward Louis had the assistance of a skilled religious statesman, Abbot Suger. Louis VI successfully defeated, both military and politically, many of the robber barons. When Louis VI died in 1137, much progress had been made towards strengthening Capetian authority.[18]

Thanks to Abbot Suger's political advice, King Louis VII (junior king 1131–37, senior king 1137–80) enjoyed greater moral authority over France than his predecessors. Powerful vassals paid homage to the French king.[19] Abbot Suger arranged the 1137 marriage between Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine in Bordeaux, which made Louis VII Duke of Aquitaine and gave him considerable power. The marriage was ultimately annulled and Eleanor soon married the Duke of Normandy — Henry Fitzempress, who would become King of England as Henry II two years later.[20]

Late Capetians (1165–1328)

The late direct Capetian kings were considerably more powerful and influential than the earliest ones. This period also saw the rise of a complex system of international alliances and conflicts opposing, through dynasties, kings of France and England and the Holy Roman Emperor. The reign of Philip II Augustus (junior king 1179–80, senior king 1180–1223) saw the French royal domain and influence greatly expanded. He set the context for the rise of power to much more powerful monarchs like Saint Louis and Philip the Fair. Philip II spent an important part of his reign fighting the so-called Angevin Empire.

During the first part of his reign Philip II allied himself with the Duke of Aquitaine and son of Henry II—Richard Lionheart—and together they launched a decisive attack on Henry's home of Chinon and removed him from power. Richard replaced his father as King of England afterward. The two kings then went crusading during the Third Crusade; however, their alliance and friendship broke down during the crusade. John Lackland, Richard's successor, refused to come to the French court for a trial against the Lusignans and, as Louis VI had done often to his rebellious vassals, Philip II confiscated John's possessions in France. John's defeat was swift and his attempts to reconquer his French possession at the decisive Battle of Bouvines (1214) resulted in complete failure. Philip II had annexed Normandy and Anjou, plus capturing the Counts of Boulogne and Flanders, although Aquitaine and Gascony remained loyal to the Plantagenet King.

Prince Louis (the future Louis VIII, reigned 1223–26) was involved in the subsequent English civil war as French and English (or rather Anglo-Norman) aristocracies were once one and were now split between allegiances. While the French kings were struggling against the Plantagenets, the Church called for the Albigensian Crusade. Southern France was then largely absorbed in the royal domains.

France became a truly centralised kingdom under Louis IX (reigned 1226–70). The kingdom was vulnerable: war was still going on in the County of Toulouse, and the royal army was occupied fighting resistance in Languedoc. Count Raymond VII of Toulouse finally signed the Treaty of Paris in 1229, in which he retained much of his lands for life, but his daughter, married to Count Alfonso of Poitou, produced him no heir and so the County of Toulouse went to the King of France. King Henry III of England had not yet recognized the Capetian overlordship over Aquitaine and still hoped to recover Normandy and Anjou and reform the Angevin Empire. He landed in 1230 at Saint-Malo with a massive force. This evolved into the Saintonge War (1242). Ultimately, Henry III was defeated and had to recognise Louis IX's overlordship, although the King of France did not seize Aquitaine. Louis IX was now the most important landowner of France. There were some opposition to his rule in Normandy, yet it proved remarkably easy to rule, especially compared to the County of Toulouse which had been brutally conquered. The Conseil du Roi, which would evolve into the Parlement, was founded in these times. After his conflict with King Henry III of England, Louis established a cordial relation with the Plantagenet King.[21]

The Kingdom was involved in two crusades under Louis: the Seventh Crusade and the Eighth Crusade. Both proved to be complete failures for the French King. Philip III became king when Saint Louis died in 1270 during the Eighth Crusade. Philip III was called "the Bold" on the basis of his abilities in combat and on horseback, and not because of his character or ruling abilities. Philip III took part in another crusading disaster: the Aragonese Crusade, which cost him his life in 1285. More administrative reforms were made by Philip IV, also called Philip the Fair (reigned 1285–1314). This king was responsible for the end of the Knights Templar, signed the Auld Alliance, and established the Parlement of Paris. Philip IV was so powerful that he could name popes and emperors, unlike the early Capetians. The papacy was moved to Avignon and all the contemporary popes were French, such as Philip IV's puppet Bertrand de Goth, Pope Clement V.

Early Valois Kings and the Hundred Years' War (1328–1453)

The tensions between the Houses of Plantagenet and Capet climaxed during the so-called Hundred Years' War (actually several distinct wars over the period 1337 to 1453) when the Plantagenets claimed the throne of France from the Valois. This was also the time of the Black Death, as well as several devastating civil wars. In 1420, by the Treaty of Troyes Henry V was made heir to Charles VI. Henry V failed to outlive Charles so it was Henry VI of England and France who consolidated the Dual-Monarchy of England and France.

It has been argued that the difficult conditions the French population suffered during the Hundred Years' War awakened French nationalism, a nationalism represented by Joan of Arc (1412–1431). Although this is debatable, the Hundred Years' War is remembered more as a Franco-English war than as a succession of feudal struggles. During this war, France evolved politically and militarily.

Although a Franco-Scottish army was successful at the Battle of Baugé (1421), the humiliating defeats of Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415) forced the French nobility to realise they could not stand just as armoured knights without an organised army. Charles VII (reigned 1422–61) established the first French standing army, the Compagnies d'ordonnance, and defeated the Plantagenets once at Patay (1429) and again, using cannons, at Formigny (1450). The Battle of Castillon (1453) was the last engagement of this war; Calais and the Channel Islands remained ruled by the Plantagenets.

Early Modern France (1453–1789)

Kings during this period

The Early Modern period in French history spans the following reigns, from 1461 to the Revolution, breaking in 1789:

- House of Valois

- Louis XI the Prudent, 1461–83

- Charles VIII the Affable, 1483–98

- Louis XII, 1498–1515

- Francis I, 1515–47

- Henry II, 1547–59

- Francis II, 1559–60

- Charles IX, 1560–74 (1560–63 under regency of Catherine de' Medici)

- Henry III, 1574–89

- House of Bourbon

- Henry IV the Great, 1589–1610

- the Regency of Marie de Medici, 1610–17

- Louis XIII the Just and his minister Cardinal Richelieu, 1610–43

- the Regency of Anne of Austria and her minister Cardinal Mazarin, 1643–51

- Louis XIV the Sun King and his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1643–1715

- the Régence, a period of regency under Philip II of Orléans, 1715–23

- Louis XV the Beloved and his minister Cardinal André-Hercule de Fleury, 1715–74

- Louis XVI, 1774–92

Life in the Early Modern period

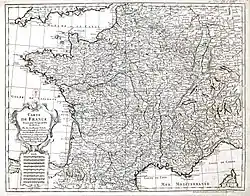

France in the Ancien Régime covered a territory of around 520,000 square kilometres (200,000 sq mi). This land supported 13 million people in 1484 and 20 million people in 1700. France had the second largest population in Europe around 1700. France's lead slowly faded after 1700, as other countries grew faster.[22]

Political power was widely dispersed. The law courts ("Parlements") were powerful. However, the king had only about 10,000 officials in royal service – very few indeed for such a large country, and with very slow internal communications over an inadequate road system. Travel was usually faster by ocean ship or river boat.[23] The different estates of the realm — the clergy, the nobility, and commoners — occasionally met together in the "Estates General", but in practice the Estates General had no power, for it could petition the king but could not pass laws.

The Catholic Church controlled about 40% of the wealth. The king (not the pope) nominated bishops, but typically had to negotiate with noble families that had close ties to local monasteries and church establishments. The nobility came second in terms of wealth, but there was no unity. Each noble had his own lands, his own network of regional connections, and his own military force.[23]

The cities had a quasi-independent status, and were largely controlled by the leading merchants and guilds. Peasants made up the vast majority of population, who in many cases had well-established rights that the authorities had to respect. In the 17th century peasants had ties to the market economy, provided much of the capital investment necessary for agricultural growth, and frequently moved from village to village (or town).[24] Although most peasants in France spoke local dialects, an official language emerged in Paris and the French language became the preferred language of Europe's aristocracy and the lingua franca of diplomacy and international relations. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V quipped, "I speak Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to my horse."[25]

Consolidation (15th and 16th centuries)

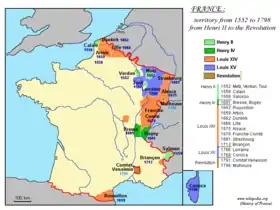

With the death in 1477 of Charles the Bold, France and the Habsburgs began a long process of dividing his rich Burgundian lands, leading to numerous wars. In 1532, Brittany was incorporated into the Kingdom of France.

France engaged in the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. Francis I faced powerful foes, and he was captured at Pavia. The French monarchy then sought for allies and found one in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Admiral Barbarossa captured Nice in 1543 and handed it down to Francis I.

During the 16th century, the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs were the dominant power in Europe. The many domains of Charles V encircled France. The Spanish Tercio was used with great success against French knights. Finally, on 7 January 1558, the Duke of Guise seized Calais from the English.

Economic historians call the era from about 1475 to 1630 the "beautiful 16th century" because of the return of peace, prosperity and optimism across the nation, and the steady growth of population. In 1559, Henry II of France signed (with the approval of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor) two treaties (Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis): one with Elizabeth I of England and one with Philip II of Spain. This ended long-lasting conflicts between France, England and Spain.

Protestant Huguenots and wars of religion (1562–1629)

The Protestant Reformation, inspired in France mainly by John Calvin, began to challenge the legitimacy and rituals of the Catholic Church.[26] French King Henry II severely persecuted Protestants under the Edict of Chateaubriand (1551).[27] Renewed Catholic reaction — headed by the powerful Francis, Duke of Guise — led to a massacre of Huguenots at Vassy in 1562, starting the first of the French Wars of Religion, during which English, German, and Spanish forces intervened on the side of rival Protestant ("Huguenot") and Catholic forces.

King Henry II died in 1559 in a jousting tournament; he was succeeded in turn by his three sons, each of which assumed the throne as minors or were weak, ineffectual rulers. In the power vacuum entered Henry's widow, Catherine de' Medici, who became a central figure in the early years of the Wars of Religion. She is often blamed for the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were murdered in Paris and the provinces of France.

The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys (1584–98), at the height of which bodyguards of the King Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic league, in December 1588. In revenge, a priest assassinated Henry III in 1589. This led to the ascension of the Huguenot Henry IV; in order to bring peace to a country beset by religious and succession wars, he converted to Catholicism. He issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which guaranteed religious liberties to the Protestants, thereby effectively ending the civil war.[28] Henry IV was assassinated in 1610 by a fanatical Catholic.

When in 1620 the Huguenots proclaimed a constitution for the 'Republic of the Reformed Churches of France', the chief minister Cardinal Richelieu invoked the entire powers of the state to stop it. Religious conflicts therefore resumed under Louis XIII when Richelieu forced Protestants to disarm their army and fortresses. This conflict ended in the Siege of La Rochelle (1627–28), in which Protestants and their English supporters were defeated. The following Peace of Alais (1629) confirmed religious freedom yet dismantled the Protestant military defences.[29]

In the face of persecution, Huguenots dispersed widely throughout Europe and America.[30]

Thirty Years' War (1618–1648)

The religious conflicts that plagued France also ravaged the Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire. The Thirty Years' War eroded the power of the Catholic Habsburgs. Although Cardinal Richelieu, the powerful chief minister of France, had mauled the Protestants, he joined this war on their side in 1636 because it was in the national interest. Imperial Habsburg forces invaded France, ravaged Champagne, and nearly threatened Paris.[31]

Richelieu died in 1642 and was succeeded by Cardinal Mazarin, while Louis XIII died one year later and was succeeded by Louis XIV. France was served by some very efficient commanders such as Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé and Henri de la Tour d'Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne. The French forces won a decisive victory at Rocroi (1643), and the Spanish army was decimated; the Tercio was broken. The Truce of Ulm (1647) and the Peace of Westphalia (1648) brought an end to the war.[31]

France was hit by civil unrest known as The Fronde which in turn evolved into the Franco-Spanish War in 1653. Louis II de Bourbon joined the Spanish army this time, but suffered a severe defeat at Dunkirk (1658) by Henry de la Tour d'Auvergne. The terms for the peace inflicted upon the Spanish kingdoms in the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) were harsh, as France annexed Northern Catalonia.[31]

Colonies (16th and 17th centuries)

During the 16th century, the king began to claim North American territories and established several colonies.[32] Jacques Cartier was one of the great explorers who ventured deep into American territories during the 16th century.

The early 17th century saw the first successful French settlements in the New World with the voyages of Samuel de Champlain.[33] The largest settlement was New France.

Louis XIV (1643–1715)

Louis XIV, known as the "Sun King", reigned over France from 1643 until 1715. Louis continued his predecessors' work of creating a centralized state governed from Paris, sought to eliminate remnants of feudalism in France, and subjugated and weakened the aristocracy. By these means he consolidated a system of absolute monarchical rule in France that endured until the French Revolution. However, Louis XIV's long reign saw France involved in many wars that drained its treasury.[34]

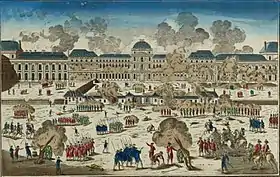

France dominated League of the Rhine fought against the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Saint Gotthard in 1664.[34] France fought the War of Devolution against Spain in 1667. France's defeat of Spain and invasion of the Spanish Netherlands alarmed England and Sweden. With the Dutch Republic they formed the Triple Alliance to check Louis XIV's expansion. Louis II de Bourbon had captured Franche-Comté, but in face of an indefensible position, Louis XIV agreed to the peace of Aachen.[35] War broke out again between France and the Dutch Republic in the Franco-Dutch War (1672–78). France attacked the Dutch Republic and was joined by England in this conflict. Through targeted inundations of polders by breaking dykes, the French invasion of the Dutch Republic was brought to a halt.[36] The Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyter inflicted a few strategic defeats on the Anglo-French naval alliance and forced England to retire from the war in 1674. Because the Netherlands could not resist indefinitely, it agreed to peace in the Treaties of Nijmegen, according to which France would annex France-Comté and acquire further concessions in the Spanish Netherlands. On 6 May 1682, the royal court moved to the lavish Palace of Versailles, which Louis XIV had greatly expanded. Over time, Louis XIV compelled many members of the nobility, especially the noble elite, to inhabit Versailles. He controlled the nobility with an elaborate system of pensions and privileges, and replaced their power with himself.

Peace did not last, and war between France and Spain again resumed.[36] The War of the Reunions broke out (1683–84), and again Spain, with its ally the Holy Roman Empire, was defeated. Meanwhile, in October 1685 Louis signed the Edict of Fontainebleau ordering the destruction of all Protestant churches and schools in France. Its immediate consequence was a large Protestant exodus from France. Over two million people died in two famines in 1693 and 1710.[36]

France would soon be involved in another war, the War of the Grand Alliance. This time the theatre was not only in Europe but also in North America. Although the war was long and difficult (it was also called the Nine Years' War), its results were inconclusive. The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 confirmed French sovereignty over Alsace, yet rejected its claims to Luxembourg. Louis also had to evacuate Catalonia and the Palatinate. This peace was considered a truce by all sides, thus war was to start again.[35]

In 1701, the War of the Spanish Succession began. The Bourbon Philip of Anjou was designated heir to the throne of Spain as Philip V. The Habsburg Emperor Leopold opposed a Bourbon succession, because the power that such a succession would bring to the Bourbon rulers of France would disturb the delicate balance of power in Europe. Therefore, he claimed the Spanish thrones for himself.[35] England and the Dutch Republic joined Leopold against Louis XIV and Philip of Anjou. They inflicted a few resounding defeats on the French army; the Battle of Blenheim in 1704 was the first major land battle lost by France since its victory at Rocroi in 1643. Yet, the extremely bloody battles of Ramillies (1706) and Malplaquet (1709) proved to be Pyrrhic victories for the allies, as they had lost too many men to continue the war.[35] Led by Villars, French forces recovered much of the lost ground in battles such as Denain (1712). Finally, a compromise was achieved with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Philip of Anjou was confirmed as Philip V, king of Spain; Emperor Leopold did not get the throne, but Philip V was barred from inheriting France.[35]

Louis XIV wanted to be remembered as a patron of the arts, and invited Jean-Baptiste Lully to establish the French opera.

The wars were so expensive, and so inconclusive, that although France gained some territory to the east, its enemies gained more strength than it did. Vauban, France's leading military strategist, warned the King in 1689 that a hostile "Alliance" was too powerful at sea. He recommended the best way for France to fight back was to license French merchants ships to privateer and seize enemy merchant ships, while avoiding its navies:

France has its declared enemies Germany and all the states that it embraces; Spain with all its dependencies in Europe, Asia, Africa and America; the Duchy of Savoy, England, Scotland, Ireland, and all their colonies in the East and West Indies; and Holland with all its possessions in the four corners of the world where it has great establishments. France has… undeclared enemies, indirectly hostile hostile and envious of its greatness, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Portugal, Venice, Genoa, and part of the Swiss Confederation, all of which states secretly aid France's enemies by the troops that they hire to them, the money they lend them and by protecting and covering their trade.[37]

Vauban was pessimistic about France's so-called friends and allies and recommended against expensive land wars, or hopeless naval wars:

For lukewarm, useless, or impotent friends, France has the Pope, who is indifferent; the King of England [James II] expelled from his country [And living in exile in Paris]; the grand Duke of Tuscany; the Dukes of Mantua, Mokena, and Parma (all in Italy); and the other faction of the Swiss. Some of these are sunk in the softness that comes of years of peace, the others are cool in their affections….The English and Dutch are the main pillars of the Alliance; they support it by making war against us in concert with the other powers, and they keep it going by means of the money that they pay every year to… Allies…. We must therefore fall back on privateering as the method of conducting war which is most feasible, simple, cheap, and safe, and which will cost least to the state, the more so since any losses will not be felt by the King, who risks virtually nothing….It will enrich the country, train many good officers for the King, and in a short time force his enemies to sue for peace.[38]

Major changes in France, Europe, and North America (1718–1783)

Louis XIV died in 1715 and was succeeded by his five-year-old great-grandson who reigned as Louis XV until his death in 1774. In 1718, France was once again at war, as Philip II of Orléans's regency joined the War of the Quadruple Alliance against Spain.[39] In 1733 another war broke in central Europe, this time about the Polish succession, and France joined the war against the Austrian Empire. Peace was settled in the Treaty of Vienna (1738), according to which France would annex, through inheritance, the Duchy of Lorraine.[39]

Two years later, in 1740, war broke out over the Austrian succession, and France seized the opportunity to join the conflict. The war played out in North America and India as well as Europe, and inconclusive terms were agreed to in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). Prussia was then becoming a new threat, as it had gained substantial territory from Austria. This led to the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, in which the alliances seen during the previous war were mostly inverted. France was now allied to Austria and Russia, while Britain was now allied to Prussia.[40]

In the North American theatre, France was allied with various Native American peoples during the Seven Years' War and, despite a temporary success at the battles of the Great Meadows and Monongahela, French forces were defeated at the disastrous Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. In 1762, Russia, France, and Austria were on the verge of crushing Prussia, when the Anglo-Prussian Alliance was saved by the Miracle of the House of Brandenburg. At sea, naval defeats against British fleets at Lagos and Quiberon Bay in 1759 and a crippling blockade forced France to keep its ships in port. Finally peace was concluded in the Treaty of Paris (1763), and France lost its North American empire.[40]

Britain's success in the Seven Years' War had allowed them to eclipse France as the leading colonial power. France sought revenge for this defeat, and under Choiseul France started to rebuild. In 1766, the French Kingdom annexed Lorraine and the following year bought Corsica from Genoa. Having lost its colonial empire, France saw a good opportunity for revenge against Britain in signing an alliance with the Americans in 1778, and sending an army and navy that turned the American Revolution into a world war. Admiral de Grasse defeated a British fleet at Chesapeake Bay while Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette joined American forces in defeating the British at Yorktown. The war was concluded by the Treaty of Paris (1783); the United States became independent. The British Royal Navy scored a major victory over France in 1782 at the Battle of the Saintes and France finished the war with huge debts and the minor gain of the island of Tobago.[41]

French Enlightenment

The "Philosophes" were 18th-century French intellectuals who dominated the French Enlightenment and were influential across Europe.[42] The philosopher Denis Diderot was editor in chief of the famous Enlightenment accomplishment, the 72,000-article Encyclopédie (1751–72).[43] It sparked a revolution in learning throughout the enlightened world.[44]

In the early part of the 18th century the movement was dominated by Voltaire and Montesquieu. Around 1750 the Philosophes reached their most influential period, as Montesquieu published Spirit of Laws (1748) and Jean Jacques Rousseau published Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences (1750). The leader of the French Enlightenment and a writer of enormous influence across Europe, was Voltaire.[45]

Astronomy, chemistry, mathematics and technology flourished. French chemists such as Antoine Lavoisier worked to replace the archaic units of weights and measures by a coherent scientific system. Lavoisier also formulated the law of Conservation of mass and discovered oxygen and hydrogen.[46]

Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_de_la_R%C3%A9volution_fran%C3%A7aise_-_Vizille.jpg.webp)

When King Louis XV died in 1774 he left his grandson, Louis XVI, "A heavy legacy, with ruined finances, unhappy subjects, and a faulty and incompetent government."[47] Wars effectively bankrupted the state. The taxation system was highly inefficient. Several years of bad harvests and an inadequate transportation system had caused rising food prices, hunger, and malnutrition; the country was further destabilized by the lower classes' increased feeling that the royal court was isolated from, and indifferent to, their hardships. In February 1787, the king's finance minister, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, convened an Assembly of Notables to approve a new land tax that would, for the first time, include a tax on the property of nobles and clergy. The assembly did not approve the tax, and instead demanded that Louis XVI call the Estates-General.

In August 1788, the King agreed to convene the Estates-General in May 1789. While the Third Estate demanded and was granted "double representation" so as to balance the First and Second Estate, voting was to occur "by orders" – votes of the Third Estate were to be weighted – effectively canceling double representation. This eventually led to the Third Estate breaking away from the Estates-General and, joined by members of the other estates, proclaiming the creation of the National Assembly, an assembly not of the Estates but of "the People". In an attempt to keep control of the process and prevent the Assembly from convening, Louis XVI ordered the closure of the Salle des États where the Assembly met. The Assembly met nearby on a tennis court and pledged the Tennis Court Oath on 20 June 1789, binding them "never to separate, and to meet wherever circumstances demand, until the constitution of the kingdom is established and affirmed on solid foundations".

Paris was soon consumed with riots and widespread looting. Because the royal leadership essentially abandoned the city, the mobs soon had the support of the French Guard, including arms and trained soldiers. On 14 July 1789, the insurgents set their eyes on the large weapons and ammunition cache inside the Bastille fortress, which also served as a symbol of royal tyranny. Insurgents seized the Bastille prison. The French now celebrate 14 July each year as 'Bastille day' or, as the French say: Quatorze Juillet (the Fourteenth of July), as a symbol of the shift away from the Ancien Régime to a more modern, democratic state.

Violence against aristocracy and abolition of feudalism (15 July – August 1789)

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, a hero of the American War of Independence, on 15 July took command of the National Guard, and the king on 17 July accepted to wear the two-colour cockade (blue and red), later adapted into the tricolour cockade, as the new symbol of revolutionary France. Although peace was made, several nobles did not regard the new order as acceptable and emigrated in order to push the neighboring, aristocratic kingdoms to war against the new regime. The state was now struck for several weeks in July and August 1789 by violence against aristocracy, also called 'the Great Fear'.

_2010-03-23_01.jpg.webp)

On 4 and 11 August 1789, the National Constituent Assembly abolished privileges and feudalism, sweeping away personal serfdom,[48] exclusive hunting rights and other seigneurial rights of the Second Estate (nobility). The tithe was also abolished.[49] The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted by the National Assembly on 27 August 1789,[50] as a first step in their effort to write a constitution.

Curtailment of Church powers (October 1789 – December 1790)

When a mob from Paris attacked the royal palace at Versailles in October 1789 seeking redress for their severe poverty, the royal family was forced to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris. In November 1789, the Assembly decided to nationalize and sell all church property,[49] thus in part addressing the financial crisis.

In July 1790, the Assembly adopted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This law reorganized the French Catholic Church, arranged that henceforth the salaries of the priests would be paid by the state,[49] abolished the Church's authority to levy a tax on crops and again cancelled some privileges for the clergy. In October a group of bishops wrote a declaration saying they could not accept the law, and this fueled civilian opposition against it. The Assembly then in late November 1790 decreed that all clergy should take an oath of loyalty to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This stiffened the resistance, especially in the west of France including Normandy, Brittany and the Vendée, where few priests took the oath and the civilian population turned against the revolution.[49] Priests swearing the oath were designated 'constitutional', and those not taking the oath as 'non-juring' or 'refractory' clergy.[51]

Making a constitutional monarchy (June–September 1791)

In June 1791, the royal family secretly fled Paris in disguise for Varennes, but they were soon discovered and returned to Paris, essentially under house arrest. In August 1791, Emperor Leopold II of Austria and King Frederick William II of Prussia in the Declaration of Pillnitz declared their intention to bring the French king in a position "to consolidate the basis of a monarchical government", and that they were preparing their own troops for action.[52] Instead of cowing the French, this infuriated them, and they militarised the borders.

With most of the Assembly still favoring a constitutional monarchy rather than a republic, the various groups reached a compromise. Under the Constitution of 3 September 1791, France would function as a constitutional monarchy. The King had to share power with the elected Legislative Assembly, although he still retained his royal veto and the ability to select ministers. He had perforce to swear an oath to the constitution, and a decree declared that retracting the oath, heading an army for the purpose of making war upon the nation or permitting anyone to do so in his name would be a de jure abdication.

War and internal uprisings (October 1791 – August 1792)

On 1 October 1791, the Legislative Assembly was formed.[53] A group of Assembly members who propagated war against Austria and Prussia was, after a remark by politician Maximilien Robespierre, henceforth designated the 'Girondins'. A group around Robespierre – later called 'Montagnards' or 'Jacobins' – pleaded against war; this opposition between those groups would harden and become bitter in the next 1+1⁄2 years.[54]

In response to the threat of war of August 1791 from Austria and Prussia, leaders of the Assembly saw such a war as a means to strengthen support for their revolutionary government, and the French people as well as the Assembly thought that they would win a war against Austria and Prussia. On 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria.[54][55] Late April 1792, France invaded and conquered the Austrian Netherlands (roughly present-day Belgium and Luxembourg).[54]

Nevertheless, in the summer of 1792, all of Paris was against the king, and hoped that the Assembly would depose the king, but the Assembly hesitated. At dawn of 10 August 1792, a crowd of Parisians and soldiers marched on the Tuileries Palace where the king resided. After 11:00am, the Assembly 'temporarily relieved the king from his task'.[56] In reaction, on 19 August an army under Prussian general Duke of Brunswick invaded France[57] and besieged Longwy.[58] Late August 1792, elections were held, now under male universal suffrage, for the new National Convention.[56] On 26 August, the Assembly decreed the deportation of refractory priests in the west of France. In reaction, peasants in the Vendée took over a town, in another step toward civil war.[58]

Bloodbath in Paris and the Republic established (September 1792)

On 2, 3 and 4 September 1792, hundreds of Parisians, supporters of the revolution, infuriated by Verdun being captured by the Prussian enemy, the uprisings in the west of France, and rumours that the incarcerated prisoners in Paris were conspiring with the foreign enemy, raided the Parisian prisons and murdered between 1,000 and 1,500 prisoners, many of them Catholic priests but also common criminals. Jean-Paul Marat, a political ally of prominent politician Robespierre, in an open letter on 3 September incited the rest of France to follow the Parisian example; Robespierre himself kept a low profile in regard to the murder orgy.[59] The Assembly and the city council of Paris (la Commune) seemed inapt and hardly motivated to call a halt to the unleashed bloodshed.[60]

On 20 September 1792, the French won a battle against Prussian troops near Valmy and the new National Convention replaced the Legislative Assembly. From the start the Convention suffered from the bitter division between a group around Robespierre, Danton and Marat referred to as 'Montagnards' or 'Jacobins' or 'left' and a group referred to as 'Girondins' or 'right'. But the majority of the representatives, referred to as 'la Plaine', were member of neither of those two antagonistic groups and managed to preserve some speed in the convention's debates.[56][61] Right away on 21 September the Convention abolished the monarchy, making France the French First Republic.[56] A new French Republican Calendar was introduced to replace the Christian Gregorian calendar, renaming the year 1792 as year 1 of the Republic.[48]

War and civil war (November 1792 – spring 1793)

With wars against Prussia and Austria having started earlier in 1792, in November France also declared war on the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic.[61] Ex-king Louis XVI was tried, convicted, and guillotined in January 1793.[62]

Introduction of a nationwide conscription for the army in February 1793 was the spark that in March made the Vendée, already rebellious since 1790 because of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy,[63] ignite into civil war against Paris.[61][64] Meanwhile, France in March also declared war on Spain.[65] That month, the Vendée rebels won some victories against Paris and the French army was defeated in Belgium by Austria with the French general Dumouriez defecting to the Austrians: the French Republic's survival was now in real danger.[65]

On 6 April 1793, to prevent the Convention from losing itself in abstract debate and to streamline government decisions, the Comité de salut public (Committee of Public Safety) was created of nine, later twelve members, as executive government which was accountable to the convention.[65] That month the 'Girondins' group indicted Jean-Paul Marat before the Revolutionary Tribunal for 'attempting to destroy the sovereignty of the people' and 'preaching plunder and massacre', referring to his behaviour during the September 1792 Paris massacres. Marat was quickly acquitted but the incident further acerbated the 'Girondins' versus 'Montagnards' party strife in the convention.[65] In the spring of 1793, Austrian, British, Dutch and Spanish troops invaded France.[64]

Showdown in the Convention (May–June 1793)

With rivalry, even enmity, in the National Convention and its predecessors between so-called 'Montagnards' and 'Girondins' smouldering ever since late 1791, Jacques Hébert, Convention member leaning to the 'Montagnards' group, on 24 May 1793 called on the sans-culottes—the idealized simple, non-aristocratic, hard-working, upright, patriotic, republican, Paris labourers—to rise in revolt against the "henchmen of Capet [=the killed ex-king] and Dumouriez [=the defected general]". Hébert was arrested immediately by a Convention committee investigating Paris rebelliousness. While that committee consisted only of members from la Plaine and the Girondins, the anger of the sans-culottes was directed towards the Girondins. 25 May, a delegation of la Commune (the Paris city council) protested against Hébert's arrest. The convention's President Isnard, a Girondin, answered them: "Members of la Commune ... If by your incessant rebellions something befalls to the representatives of the nation, I declare, in the name of France, that Paris will be totally obliterated".[61]

On 29 May 1793, in Lyon an uprising overthrew a group of Montagnards ruling the city; Marseille, Toulon and more cities saw similar events.[63]

On 2 June 1793, the convention's session in Tuileries Palace—since early May their venue—not for the first time degenerated into chaos and pandemonium. This time crowds of people including 80,000 armed soldiers swarmed in and around the palace. Incessant screaming from the public galleries, always in favour of the Montagnards, suggested that all of Paris was against the Girondins, which was not really the case. Petitions circulated, indicting and condemning 22 Girondins. Barère, member of the Committee of Public Safety, suggested: to end this division which is harming the Republic, the Girondin leaders should lay down their offices voluntarily. A decree was adopted that day by the convention, after much tumultuous debate, expelling 22 leading Girondins from the convention. Late that night, indeed dozens of Girondins had resigned and left the convention.[65]

In the course of 1793, the Holy Roman Empire, the kings of Portugal and Naples and the Grand-Duke of Tuscany declared war against France.[66]

Counter-revolution subdued (July 1793 – April 1794)

By the summer of 1793, most French departments in one way or another opposed the central Paris government, and in many cases 'Girondins', fled from Paris after 2 June, led those revolts.[67] In Brittany's countryside, the people rejecting the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790 had taken to a guerrilla warfare known as Chouannerie.[63] But generally, the French opposition against 'Paris' had now evolved into a plain struggle for power over the country[67] against the 'Montagnards' around Robespierre and Marat now dominating Paris.[63]

In June–July 1793, Bordeaux, Marseilles, Brittany, Caen and the rest of Normandy gathered armies to march on Paris and against 'the revolution'.[64][63] In July, Lyon guillotined the deposed 'Montagnard' head of the city council.[63] Barère, member of the Committee of Public Safety, on 1 August incited the convention to tougher measures against the Vendée, at war with Paris since March: "We'll have peace only when no Vendée remains ... we'll have to exterminate that rebellious people".[64] In August, Convention troops besieged Lyon.[63]

In August–September 1793, militants urged the convention to do more to quell the counter-revolution. A delegation of the Commune (Paris city council) suggested to form revolutionary armies to arrest hoarders and conspirators.[63] Bertrand Barère, member of the Committee of Public Safety—the de facto executive government—ever since April 1793,[68] among others on 5 September reacted favorably, saying: let's "make terror the order of the day!"[63] On 17 September, the National Convention passed the Law of Suspects, a decree ordering the arrest of all declared opponents of the current form of government and suspected "enemies of freedom". This decree was one of the causes for 17,000 death sentences until the end of July 1794, reason for historians to label those 10+1⁄2 months 'the (Reign of) Terror'.[69][70]

On 19 September the Vendée rebels again defeated a Republican Convention army. On 1 October Barère repeated his plea to subdue the Vendée: "refuge of fanaticism, where priests have raised their altars".[64] In October the Convention troops captured Lyon and reinstated a Montagnard government there.[63]

Criteria for bringing someone before the Revolutionary Tribunal, created March 1793, had always been vast and vague.[67] By August, political disagreement seemed enough to be summoned before the Tribunal; appeal against a Tribunal verdict was impossible.[63] Late August 1793, an army general had been guillotined on the accusation of choosing too timid strategies on the battlefield.[63] Mid-October, the widowed former queen Marie Antoinette was on trial for a long list of charges such as "teaching [her husband] Louis Capet the art of dissimulation" and incest with her son, she too was guillotined.[63] In October, 21 former 'Girondins' Convention members who had not left Paris after June were convicted to death and executed, on the charge of verbally supporting the preparation of an insurrection in Caen by fellow-Girondins.[63]

On 17 October 1793, the 'blue' Republican army near Cholet defeated the 'white' Vendéan insubordinate army and all surviving Vendée residents, counting in tens of thousands, fled over the river Loire north into Brittany.[64] A Convention's representative on mission in Nantes commissioned in October to pacify the region did so by simply drowning prisoners in the river Loire: until February 1794 he drowned at least 4,000.[67] By November 1793, the revolts in Normandy, Bordeaux and Lyon were overcome, in December also that in Toulon.[63] Two representatives on mission sent to punish Lyon between November 1793 and April 1794 executed 2,000 people by guillotine or firing-squad.[67] The Vendéan army since October roaming through Brittany on 12 December 1793 again ran up against Republican troops and saw 10,000 of its rebels perish, meaning the end of this once threatening army.[67] Some historians claim that after that defeat Convention Republic armies in 1794 massacred 117,000 Vendéan civilians to obliterate the Vendéan people, but others contest that claim.[71] Some historians consider the civil war to have lasted until 1796 with a toll of 450,000 lives.[72][73]

Death-sentencing politicians (February–July 1794)

Maximilien Robespierre, since July 1793 member of the Committee of Public Prosperity,[64] on 5 February 1794 in a speech in the Convention identified Jacques Hébert and his faction as "internal enemies" working toward the triumph of tyranny. After a dubious trial Hébert and some allies were guillotined in March.[67] On 5 April, again at the instigation of Robespierre, Danton and 13 associated politicians were executed. A week later again 19 politicians. This hushed the Convention deputies: if henceforth they disagreed with Robespierre they hardly dared to speak out.[67] A law enacted on 10 June 1794 (22 Prairial II) further streamlined criminal procedures: if the Revolutionary Tribunal saw sufficient proof of someone being an "enemy of the people" a counsel for defence would not be allowed. The frequency of guillotine executions in Paris now rose from on average three a day to an average of 29 a day.[67]

Meanwhile, France's external wars were going well, with victories over Austrian and British troops in May and June 1794 opening up Belgium for French conquest.[67] However, cooperation within the Committee of Public Safety, since April 1793 the de facto executive government, started to break down. On 29 June 1794, three colleagues of Robespierre at the Committee called him a dictator in his face; Robespierre, baffled, left the meeting. This encouraged other Convention members to also defy Robespierre. On 26 July, a long and vague speech of Robespierre was not met with thunderous applause as usual but with hostility; some deputies yelled that Robespierre should have the courage to say which deputies he deemed necessary to be killed next, which Robespierre refused to do.[67]

In the Convention session of 27 July 1794, Robespierre and his allies hardly managed to say a word as they were constantly interrupted by a row of critics such as Tallien, Billaud-Varenne, Vadier, Barère and acting president Thuriot. Finally, even Robespierre's own voice failed on him: it faltered at his last attempt to beg permission to speak. A decree was adopted to arrest Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon. On 28 July, they and 19 others were beheaded. On 29 July, again 70 Parisians were guillotined.[68] Subsequently, the Law of 22 Prairial (10 June 1794) was repealed, and the 'Girondins' expelled from the Convention in June 1793, if not dead yet, were reinstated as Convention deputies.[74]

Disregarding the working classes (August 1794 – October 1795)

After July 1794, most civilians henceforth ignored the Republican calendar and returned to the traditional seven-day weeks. The government in a law of 21 February 1795 set steps of return to freedom of religion and reconciliation with the since 1790 refractory Catholic priests, but any religious signs outside churches or private homes, such as crosses, clerical garb, bell ringing, remained prohibited. When the people's enthusiasm for attending church grew to unexpected levels the government backed out and in October 1795 again, like in 1790, required all priests to swear oaths on the Republic.[74]

In the very cold winter of 1794–95, with the French army demanding more and more bread, the same was getting scarce in Paris, as was wood to keep houses warm, and in an echo of the October 1789 March on Versailles, on 1 April 1795 (12 Germinal III) a mostly female crowd marched on the Convention calling for bread. But no Convention member sympathized; they just told the women to return home. Again in May a crowd of 20,000 men and 40,000 women invaded the convention and even killed a deputy in the halls, but again they failed to make the Convention take notice of the needs of the lower classes. Instead, the Convention banned women from all political assemblies, and deputies who had solidarized with this insurrection were sentenced to death: such allegiance between parliament and street fighting was no longer tolerated.[74]

Late 1794, France conquered present-day Belgium.[75] In January 1795 they subdued the Dutch Republic with full consent and cooperation of the influential Dutch patriottenbeweging ('patriots' movement'), resulting in the Batavian Republic, a satellite and puppet state of France.[76][77] In April 1795, France concluded a peace agreement with Prussia;[78] later that year peace was agreed with Spain.[79]

Fighting Catholicism and royalism (October 1795 – November 1799)

In October 1795, the Republic was reorganised, replacing the one-chamber parliament (the National Convention) by a bi-cameral system: the first chamber called the 'Council of 500' initiating the laws, the second the 'Council of Elders' reviewing and approving or not the passed laws. Each year, one-third of the chambers was to be renewed. The executive power lay with five directors – hence the name 'Directory' for this form of government – with a five-year mandate, each year one of them being replaced.[74] The early directors did not much understand the nation they were governing; they especially had an innate inability to see Catholicism as anything other than counter-revolutionary and royalist. Local administrators had a better sense of people's priorities, and one of them wrote to the minister of the interior: "Give back the crosses, the church bells, the Sundays, and everyone will cry: 'vive la République!'"[74]

French armies in 1796 advanced into Germany, Austria and Italy. In 1797, France conquered the Rhineland, Belgium and much of Italy, and unsuccessfully attacked Wales.

Parliamentary elections in the spring of 1797 resulted in considerable gains for the royalists. This frightened the republican directors and they staged a coup d'état on 4 September 1797 (Coup of 18 Fructidor V) to remove two supposedly pro-royalist directors and some prominent royalists from both Councils.[74] The new, 'corrected' government, still strongly convinced that Catholicism and royalism were equally dangerous to the Republic, started a fresh campaign to promote the Republican calendar officially introduced in 1792, with its ten-day week, and tried to hallow the tenth day, décadi, as substitute for the Christian Sunday. Not only citizens opposed and even mocked such decrees, also local government officials refused to enforce such laws.[74]

France was still waging wars, in 1798 in Egypt, Switzerland, Rome, Ireland, Belgium and against the U.S.A., in 1799 in Baden-Württemberg. In 1799, when the French armies abroad experienced some setbacks, the newly chosen director Sieyes considered a new overhaul necessary for the Directory's form of government because in his opinion it needed a stronger executive. Together with general Napoleon Bonaparte who had just returned to France, Sieyes began preparing another coup d'état, which took place on 9–10 November 1799 (18–19 Brumaire VIII), replacing the five directors now with three "consuls": Napoleon, Sieyes, and Roger Ducos.[74]

Napoleonic France (1799–1815)

During the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797), the Directory had replaced the National Convention. Five directors then ruled France. As Great Britain was still at war with France, a plan was made to take Egypt from the Ottoman Empire, a British ally. This was Napoleon's idea and the Directory agreed to the plan in order to send the popular general away from the mainland. Napoleon defeated the Ottoman forces during the Battle of the Pyramids (21 July 1798) and sent hundreds of scientists and linguists out to thoroughly explore modern and ancient Egypt. Only a few weeks later the British fleet under Admiral Horatio Nelson unexpectedly destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile (1–3 August 1798). Napoleon planned to move into Syria but was defeated at the Siege of Acre and he returned to France without his army, which surrendered.[80]

The Directory was threatened by the Second Coalition (1798–1802). Royalists and their allies still dreamed of restoring the monarchy to power, while the Prussian and Austrian crowns did not accept their territorial losses during the previous war. In 1799, the Russian army expelled the French from Italy in battles such as Cassano, while the Austrian army defeated the French in Switzerland at Stockach and Zurich. Napoleon then seized power through a coup and established the Consulate in 1799. The Austrian army was defeated at the Battle of Marengo (1800) and again at the Battle of Hohenlinden (1800).[81]

While at sea the French had some success at Boulogne but Nelson's Royal Navy destroyed an anchored Danish and Norwegian fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) because the Scandinavian kingdoms were against the British blockade of France. The Second Coalition was beaten and peace was settled in two distinct treaties: the Treaty of Lunéville and the Treaty of Amiens. A brief interlude of peace ensued in 1802–03, during which Napoleon sold French Louisiana to the United States because it was indefensible.[81]

In 1801, Napoleon concluded a "Concordat" with Pope Pius VII that opened peaceful relations between church and state in France. The policies of the Revolution were reversed, except the Church did not get its lands back. Bishops and clergy were to receive state salaries, and the government would pay for the building and maintenance of churches.[82] Napoleon reorganized higher learning by dividing the Institut National into four (later five) academies.

.jpg.webp)

In 1804, Napoleon was titled Emperor by the senate, thus founding the First French Empire. Napoleon's rule was constitutional, and although autocratic, it was much more advanced than traditional European monarchies of the time. The proclamation of the French Empire was met by the Third Coalition. The French army was renamed La Grande Armée in 1805 and Napoleon used propaganda and nationalism to control the French population. The French army achieved a resounding victory at Ulm (16–19 October 1805), where an entire Austrian army was captured.[83]

A Franco-Spanish fleet was defeated at Trafalgar (21 October 1805) and all plans to invade Britain were then made impossible. Despite this naval defeat, it was on land that this war would be won; Napoleon inflicted on the Austrian and Russian Empires one of their greatest defeats at Austerlitz (also known as the "Battle of the Three Emperors" on 2 December 1805), destroying the Third Coalition. Peace was settled in the Treaty of Pressburg; the Austrian Empire lost the title of Holy Roman Emperor and the Confederation of the Rhine was created by Napoleon over former Austrian territories.[83]

Coalitions formed against Napoleon

Prussia joined Britain and Russia, thus forming the Fourth Coalition. Although the Coalition was joined by other allies, the French Empire was also not alone since it now had a complex network of allies and subject states. The largely outnumbered French army crushed the Prussian army at Jena-Auerstedt in 1806; Napoleon captured Berlin and went as far as Eastern Prussia. There the Russian Empire was defeated at the Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807). Peace was dictated in the Treaties of Tilsit, in which Russia had to join the Continental System, and Prussia handed half of its territories to France. The Duchy of Warsaw was formed over these territorial losses, and Polish troops entered the Grande Armée in significant numbers.[84]

In order to ruin the British economy, Napoleon set up the Continental System in 1807, and tried to prevent merchants across Europe from trading with British. The large amount of smuggling frustrated Napoleon, and did more harm to his economy than to his enemies'.[85]

Freed from his obligation in the east, Napoleon then went back to the west, as the French Empire was still at war with Britain. Only two countries remained neutral in the war: Sweden and Portugal, and Napoleon then looked toward the latter. In the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1807), a Franco-Spanish alliance against Portugal was sealed as Spain eyed Portuguese territories. French armies entered Spain in order to attack Portugal, but then seized Spanish fortresses and took over the kingdom by surprise. Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother, was made King of Spain after Charles IV abdicated.[86]

This occupation of the Iberian peninsula fueled local nationalism, and soon the Spanish and Portuguese fought the French using guerilla tactics, defeating the French forces at the Battle of Bailén (June and July 1808). Britain sent a short-lived ground support force to Portugal, and French forces evacuated Portugal as defined in the Convention of Sintra following the Allied victory at Vimeiro (21 August 1808). France only controlled Catalonia and Navarre and could have been definitely expelled from the Iberian peninsula had the Spanish armies attacked again, but the Spanish did not.[87]

Another French attack was launched on Spain, led by Napoleon himself, and was described as "an avalanche of fire and steel". However, the French Empire was no longer regarded as invincible by European powers. In 1808, Austria formed the Fifth Coalition in order to break down the French Empire. The Austrian Empire defeated the French at Aspern-Essling, yet was beaten at Wagram while the Polish allies defeated the Austrian Empire at Raszyn (April 1809). Although not as decisive as the previous Austrian defeats, the peace treaty in October 1809 stripped Austria of a large amount of territory, reducing it even more.

In 1812, war broke out with Russia, engaging Napoleon in the disastrous French invasion of Russia (1812). Napoleon assembled the largest army Europe had ever seen, including troops from all subject states, to invade Russia, which had just left the continental system and was gathering an army on the Polish frontier. Following an exhausting march and the bloody but inconclusive Battle of Borodino, near Moscow, the Grande Armée entered and captured Moscow, only to find it burning as part of the Russian scorched earth tactics. Although there still were battles, the Napoleonic army left Russia in late 1812 annihilated, most of all by the Russian winter, exhaustion, and scorched earth warfare. On the Spanish front the French troops were defeated at Vitoria (June 1813) and then at the Battle of the Pyrenees (July–August 1813). Since the Spanish guerrillas seemed to be uncontrollable, the French troops eventually evacuated Spain.[88]

Since France had been defeated on these two fronts, states that had been conquered and controlled by Napoleon saw a good opportunity to strike back. The Sixth Coalition was formed under British leadership.[89] The German states of the Confederation of the Rhine switched sides, finally opposing Napoleon. Napoleon was largely defeated in the Battle of the Nations outside Leipzig in October 1813, his forces heavily outnumbered by the Allied coalition armies and was overwhelmed by much larger armies during the Six Days Campaign (February 1814), although, the Six Days Campaign is often considered a tactical masterpiece because the allies suffered much higher casualties. Napoleon abdicated on 6 April 1814, and was exiled to Elba.[90]

The conservative Congress of Vienna reversed the political changes that had occurred during the wars. Napoleon suddenly returned, seized control of France, raised an army, and marched on his enemies in the Hundred Days. It ended with his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and his exile to St. Helena, a remote island in the South Atlantic Ocean.[91]

The monarchy was subsequently restored and Louis XVIII, Younger brother of Louis XVI became king, and the exiles returned. However many of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic reforms were kept in place.[92]

Napoleon's impact on France