Taba language

Taba (also known as East Makian or Makian Dalam) is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the South Halmahera–West New Guinea group. It is spoken mostly on the islands of Makian, Kayoa and southern Halmahera in North Maluku province of Indonesia by about 20,000 people.[2]

| Taba | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | North Maluku province |

Native speakers | (20,000+ cited 1983)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mky |

| Glottolog | east2440 |

| ELP | Taba |

Dialects

There are minor differences in dialect between all of the villages on Makian island in which Taba is spoken. Most differences affect only a few words. One of the most widespread reflexes is the use of /o/ in Waikyon and Waigitang, where in other villages /a/ is retained from Proto-South Halmaheran.[3]

Geographic distribution

As of 2005, Ethnologue lists Taba as having a speaking population of approximately 20,000; however, it has been argued by linguists that this number could in reality be anywhere between 20,000 and 50,000.[4] The language is predominantly spoken on Eastern Makian island, although it is also found on Southern Mori island, Kayoa islands, Bacan and Obi island and along the west coast of south Halmahera. There has also been continued migration of speakers to other areas of North Maluku due to frequent volcanic eruptions on Makian island.[5] The island itself is home to two languages: Taba, which is spoken on the eastern side of the island, and a Papuan language spoken on the western side, known alternatively as West Makian or Makian Luar (outer Makian); in Taba, this language is known as Taba Lik ('Outer Taba'), while its native speakers know it as Moi.

Speech levels

Taba is divided into three different levels of speech: alus, biasa and kasar.

Alus, or 'refined' Taba, is used in situations in which the speaker is addressing someone older or of greater status than the speaker themselves.

Biasa, or 'ordinary' Taba, is used in most general situations.

The Kasar, or 'coarse' form of Taba, is used only rarely and generally in anger.

Phonology

Taba has fifteen indigenous consonant phonemes, and four loan phonemes: /ʔ dʒ tʃ f/. These are shown below:

| Bilabial | Apico- alveolar |

Lamino- palatal |

Dorso- velar |

Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | (tʃ) | k | (ʔ) |

| voiced | b | d | (dʒ) | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | (f) | s | ||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | h | ||

Syllables may only have complex onsets at the beginning of morphemic units. The minimal Taba syllable consists of just a vowel, while the maximal indigenous syllable structure is CCVC (there are some examples of CCCVC from Dutch). The structure CCVC, however, is only found in syllables which occur at the beginning of morphemes; non-initial syllables have a maximal structure of CVC. The vast majority of words are mono- or disyllabic.

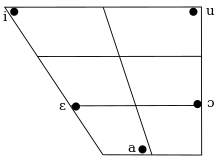

Taba has five vowels, illustrated on the table below. The front and central vowels are unrounded; the back vowels are rounded.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

Grammar

Word order

Taba is, predominantly, a head-marking language which adheres to a basic AVO word order. However, there is a reasonable degree of flexibility.[8]

yak

1SG

k=ha-lekat

1SG=CAUS-broken

pakakas

tool

ne

PROX

'I broke this tool.'

Taba has both prepositions and postpositions.

Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | yak | am |

| inclusive | tit | ||

| 2nd person | au | meu | |

| 3rd person | i | si | |

In Taba, pronouns constitute an independent, closed set. Syntactically, Taba pronouns can be used in any context where a full noun phrase is applicable. However, independent pronouns are only used in reference to animate entities, unless pronominal reference to inanimate patients is required in reflexive clauses.[10]

As mentioned, independent pronouns are generally used for animate reference. However, there are two exceptions to this generalisation. In some circumstances an inanimate is considered a 'higher inanimate' which accords syntactic status similar to animates.[10] This is represented as in English where inanimates such as cars or ships, for example, can be ascribed a gender. This is illustrated below in a response to the question 'Why did the Taba Jaya (name of a boat) stop coming to Makian?':[10]

Ttumo

t=tum-o

1PL.INCL=follow-APPL

i

i

3SG

te

te

NEG

ndara

ndara

too.much

'We didn't catch it enough.'

The Taba Jaya, a boat significant enough to be given a name, is accorded pronoun status similar to animates. The other exception occurs in reflexive clauses where a pronominal copy of a reflexive patient is required, as shown below:[10]

Bonci

bonci

peanut

ncayak

n-say-ak

3SG-spread-APPL

i

i

3SG

tadia

ta-dia

SIM-REM

'Peanut (leaves) spread out on itself like that.'

Non-human animates and inanimates are always grammatically singular, regardless of how many referents are involved. In Taba, pronouns and noun phrases are marked by person and number.

Person

Taba distinguishes three persons in the pronominal and cross-referencing systems.[10] Person is marked on both pronouns and on cross-referencing proclitics attached to verb phrases.[11] The actor cross-referencing proclitics are outlined in the following table.[12] In the first-person plural, a clusivity distinction is made, 'inclusive' (including the addressee) and 'exclusive' (excluding the addressee), as is common to most Austronesian languages.[12]

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | k= | a= |

| inclusive | t= | ||

| 2nd person | m= | h= | |

| 3rd person | n= | l= | |

The following are examples (4–10) of simple actor intransitive clauses showing each of the proclitic prefixes.

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | yak yak 1SG kwom k=wom 1SG=come 'I've come' |

Am am 1PL.EXCL awom a=wom 1PL.EXCL=come 'We've come. (myself and one or more other people but not you)' |

| inclusive | Tit tit 1PL.INCL twom t=wom 1PL.INCL=come 'We've come. (You and I)' | ||

| 2nd person | Au au 2SG mwom m=wom 2SG=come 'You've come. (you singular)' |

Meu meu 2PL hwom h=wom 2PL=come 'You've come. (you plural)' | |

| 3rd person | I i 3SG nwom n=wom 3SG=come 'S/he's come.' |

Si si 3PL lwom l=wom 3PL=come 'They've come.' | |

The alternation between proclitic markers indicates number, where in (4) k= denotes the arrival of a singular actor, while in (7) a= indicates the arrival of first-person plural actors, exclusionary of the addressee, and is replicated in the change of prefix in the additional examples.

Number

Number is marked on noun phrases and pronouns. Taba distinguishes grammatically between singular and plural categories, as shown in (3) to (9) above. Plural marking is obligatory for humans and is used for all noun phrases which refer to multiple individuals. Plurality is also used to indicate respect in the second and third Person when addressing or speaking of an individual who is older than the speaker.[3] The rules for marking number on noun phrases are summarised in the table below:[3]

| Marking Number | ||

|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | |

| human | Used for one person when person is same age or younger than speaker. | Used for one person when person is older than speaker. Used for more than one person in all contexts. |

| non-human animate | Used no matter how many referents | Not used |

| inanimate | Used no matter how many referents | Not used |

The enclitic =si marks number in noun phrases. =si below (10), indicates that there is more than one child playing on the beach and, in (11), the enclitic indicates that the noun phase mama lo baba, translated as 'mother and father,' is plural.[3]

Wangsi

wang=si

child=PL

lalawa

l=ha=lawa

3pl=CAUS-play

lawe

la-we

sea-ESS

solo

solo

beach

li

li

LOC

'The children are playing on the beach.'

Nim

nim

2SG.POSS

mama

mama

mother

li

lo

and

babasi

baba=si

father=PL

laoblak

l-ha=obal-k

3PL=CAUS-call-APPL

'Your mother and father are calling you.'

Plural number is used as a marker of respect not only for second-person addressees, but for third-person referents as seen in (12).[3] In Taba, it has been observed that many adults use deictic shifts towards the perspective of addressee children regarding the use of plural markers. Example (13) is typical of an utterance of an older person than those they are referring to, indicative of respect that should be accorded to the referent by the addressee.[3]

Ksung

k=sung

1SG=enter

Om

Om

Uncle

Nur

Nur

Nur

nidi

nidi

3PL.POSS

um

um

house

li

li

LOC

'I went into Om Nur's house.'

Nim

nim

2SG.POSS

babasi

baba=si

father=PL

e

e

FOC

lo

lo

where

li

li

LOC

e?

e

FOC

'Where is your father?'

Pronominal affixes

All Taba verbs having actor arguments carry affixes which cross-reference the number and person of the actor, examples of proclitics are shown above. In Taba, there are valence-changing affixes which deal with patterns of cross-referencing with three distinct patterns. The dominant pattern is used with all verbs having an actor argument. The other two patterns are confined to a small number of verbs: one for the possessive verb, the other for a few verbs of excretion. This is discussed further in Possession below.

Possession

Taba does not, as such, have possessive pronouns. Rather, the possessor noun and the possessed entity are linked by a possessive ligature. The Taba ligatures are shown below:

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | nik | am |

| inclusive | nit | ||

| 2nd person | nim | meu | |

| 3rd person | ni | nidi/di | |

Adnominal possession

Adnominal possession involves the introduction of an inflected possessive particle between the possessor and the possessed entity; this inflected possessive, formally categorised as a 'ligature', is cross-referenced with the number and person of the possessor. This ligature indicates a possessive relationship between a modifier noun and its head-noun. In Taba, adnominal possession is distinguished by reverse genitive ordering, in which the possessor noun precedes the noun referring to the possessed entity.[13]

In many contexts the possessor will not be overtly referenced.

Example of reverse genitive ordering in Taba:

ni

3SG.POSS

mtu

child

'His/her child.'

Obligatory possessive marking

In Taba, alienable and inalienable possession is not obligatorily marked by the use of different forms, though this is common in many related languages. However, there are a number of seemingly inalienable entities which cannot be referred to without referencing a possessor.[14]

For example:

meja

table

ni

3SG.POSS

wwe

leg

'The leg (of the table).'

Verbal possession

Verbal possession in Taba is generally indicated through the attaching of the causative prefix ha- to the adnominal possessive forms. The possessor then becomes actor of the clause, and the possessed entity becomes the undergoer.[15] This method of forming a possessive verb is very unusual, typologically, and is found in almost no other languages.[16]

kabin

goat

da

DIST

yak

1SG

k=ha-nik

1SG=CAUS-1SG.POSS

'That goat, I own it.'

Negation

Like other Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages spoken in the Maluku Islands, Taba uses different particles to negate declarative and imperative clauses;[17] declaratives are negated using te, while imperatives are negated using oik.[18] In both cases the negative particles are clause-final, a placement which is posited to be the result of contact with non-Austronesian Papuan languages.[19]

Negation of declaratives using te

Declarative clauses are negated using the particle te, which follows all other elements of the clause except for modal and aspectual particles (these are discussed below).[20] Examples (15a) and (15b) show negation of an actor intransitive clause, while (16a) and (16b) give negation of a non-actor bivalent clause (i.e. a clause with two undergoer arguments); te has the same clause-final placement regardless of the clause structure.

Nhan

n=han

3sg=go

akla

ak-la

ALL-sea

'She's going seawards.' (Bowden 2001, p. 335)

Nhan

n=han

3sg=go

akla

ak-la

ALL-sea

te

te

NEG

'She's not going seawards.' (Bowden 2001, p. 335)

Nik

nik

1sg.POSS

calana

ak-lacalana

trousers

kudak

kuda-k

be.black-APPL

asfal

asfal

bitumen

'My trousers are blackened with bitumen.' (Bowden 2001, p. 336)

Nik

nik

1sg.POSS

calana

ak-lacalana

trousers

kudak

kuda-k

be.black-APPL

asfal

asfal

bitumen

te

te

NEG

'My trousers are not blackened with bitumen.' (Bowden 2001, p. 336)

Negation of complex sentences can be ambiguous — see example (17), where te can operate on either just the complement clause khan 'I'm going' or to the whole clause complex kalusa khan 'I said I'm going':[21]

Kalusa

k=ha-lusa

1sg=CAUS-say

khan

k=han

1sg=go

te

te

NEG

'I said I'm not going.' / 'I didn't say I'm going.' (Bowden 2001, p. 335)

Negative existential clauses[21]

Te can serve as the predicator of a negative existential clause, with no verb required. It can occur immediately following the noun phrase that refers to whatever is being asserted as non-existent, as in (18):

Nik

nik

1sg.POSS

dalawat

dalawat

girlfriend

te

te

NEG

'I don't have a girlfriend.' (Bowden 2001, p. 336)

However, a discourse marker is generally interposed between the noun phrase and te. This marker expresses something about how the non-existence of the noun phrase's referent relates to the discourse context, or alternatively indicates the speaker's attitude towards the proposition.[21] In (19), the discourse marker mai (glossed as 'but') is used to indicate that the non-existence of tea, sugar and coffee in the household described by the speaker is counter to one's expectations that a normal household would have these items:

Te

tea

mai

but

te;

NEG

gula

sugar

mai

but

te;

NEG

kofi

coffee

mai

but

te

NEG

'There's no tea; there's no sugar; there's no coffee.' (Bowden 2001, p. 336)

Complex negative modal / aspectual particles[22]

Taba has three complex negative particles which, in addition to negation, express mood or aspect; these are formed by the modal and aspectual particles attaching onto te as clitics. The three particles are tedo (realis negative), tehu (continuative negative), and tesu (potential negative).

tedo (realis negative)[23]

Tedo is a compound of te and the realis mood marker do, and expresses a more emphatic negation than plain te. In (20), it is used to emphasize the absolute nature of the prohibition against making alcohol in the Muslim community of the speaker:

Mai

mai

but

ane

a-ne

DEM-PROX

lpeik

l=pe-ik

3pl=make-APPL

saguer

saguer

palm.wine

tedo.

te-do

NEG-REAL

'But here they don't make palm wine with it anymore.' (Bowden 2001, p. 338)

tehu (continuative negative)[24]

Tehu is a compound of te and the continuous aspect marker hu, and can be roughly translated as 'not up to the relevant point in time': this may be either the time of utterance (i.e. 'not yet', 'still not'), or some other time relevant to the context of the utterance, as in (21). Unlike the potential negative tesu, tehu does not express any expectations about the likelihood of the negated event or state occurring in the future.

Manganco

manganco

long.time

ne

ne

PROX

dukon

dukon

eruption

tehu

te-hu

NEG-CONT

'For a long time there hadn't been an eruption.' (Bowden 2001, p. 338)

Tehu also often appears at the end of the first clause in a sequence of clauses, indicating whatever is referred to by the first clause has not still occurred by the time of the event(s) or state(s) referred to by the following clauses.

Karna

karna

because

taplod

ta-plod

DETR-erupt

tehu,

te-hu

NEG-CONT

manusia

manusia

people

loas

l=oas

3pl=flee

do.

do

REAL

'Because the mountain had still not erupted when everyone fled.' (Bowden 2001, p. 338)

tesu (potential negative)[25]

Tesu is formed by suffixing -su, expressing the potential mood, to te. Although tesu is similar to tehu in that it encodes the meaning 'not up to the relevant point in time', it also expresses an expectation that the event referred to will occur in the future: this expectation is made explicit in the free translation of (23).

Sedi

sedi

garden.shelter

ne

ne

PROX

dumik

dumik

be.complete

tesu

te-su

NEG-POT

'This garden shelter is not yet finished.' [but I expect it to be finished later] (Bowden 2001, p. 339)

Tesu shares with tehu the ability to be used at the end of the first clause in a sequence of clauses, and also carries a similar meaning of incompletion; in addition, it encodes the expectation that the event referred to by the first clause should have happened by the event(s) of the following clauses. This expectation does not need to have actually been fulfilled; the breakfast that was expected to be cooked in the first clause of (24) was, in reality, never cooked due to the ensuing eruption.

Hadala

hadala

breakfast

mosa

mosa

be.cooked

tesu,

te-su

NEG-POT

taplod

ta-plod

DETR-erupt

haso

ha=so

CL=one

nak.

nak

also

'Breakfast was still not cooked (although I had every expectation that it would be) when it erupted again.' (Bowden 2001, p. 339)

Unlike the modal and aspectual markers which are used to form the other complex negative particles, su is not attested as a free morpheme elsewhere; however, it is likely related to the optional final -s of the modal verb -ahate(s) 'to be unable', which appears to be derived historically from te having fused onto the verb -ahan 'to be able'.[26] When used with a final -s, as in (25b) compared with (25a), this modal verb encodes the same meanings expressed by tesu:

Irianti

Irianti

Irianti

nasodas

n=ha-sodas

3sg=CAUS-suck[smoke]

nahate

n=ahate

3sg=be.unable

'Irianti is not allowed to smoke.' (Bowden 2001, p. 317)

Iswan

Iswan

Iswan

nasodas

n=ha-sodas

3sg=CAUS-suck[smoke]

nahates

n=ahate-s

3sg=be.unable-POT

'Iswan is not allowed to smoke (now. But he will be allowed to in the future).' (Bowden 2001, p. 318)

Negation of imperatives using oik

Imperative clauses are negated using the admonitive particle oik. This particle appears to be derived from a verb oik 'to leave something behind'; however, this verb requires actor cross-referencing, whereas the particle is never cross-referenced.[27] Bowden (2001) posits that the imperative use of oik has developed from the use of the independent verb in serial verb constructions, with the morphological elements being lost in the process of grammaticalization.[28] The particle is shown in (26), while the verbal use (with cross-referencing) is shown in (27):

Hmomas

h=momas

2PL=wipe

meu

meu

2PL.POSS

komo

komo

hand

mai

mai

but

hmomsak

h=momas=ak

2PL=wipe=APPL

meu

meu

2PL.POSS

calana

calana

trousers

oik

oik

ADMON

'Wipe your hands, but don't wipe them with your trousers.' (Bowden 2001, p. 337)

Nim

nim

2SG.POSS

suka

suka

desire

moik

m=oik

2SG=leave.behind

nim

nim

2SG.POSS

sagala

sagala

stuff

ane?

a-ne

LOC-PROX

'Do you want to leave your stuff behind here?' (Bowden 2001, p. 337)

Using negative particles as question tags

Yes–no (polar) questions can be posed with either positive or negative polarity; positive polarity questions operate in much the same way as in English, while negative polarity questions, which are formed using forms of the negative marker te as question tags, work in a different manner.[29] An example of a positive polarity question is given below in (28a), while (28b) shows a negative polarity question:

Masodas

m=ha-sodas

2sg=CAUS-suck

pa

pa

or

ne?

ne

PROX

'Do you smoke?' (Bowden 2001, p. 356)

Masodas

m=ha-sodas

2sg=CAUS-suck

pa

pa

or

te?

te

NEG

'Do you smoke or not?' (Bowden 2001, p. 356)

The answers to the positive polarity may be either Jou/Ole ('Yes, I do smoke') or Te ('No, I don't smoke'); when responding to the negative polarity question, the answers are either Jou/Ole ('Yes, I do not smoke'), Te ('No, I do smoke').[29]

Demonstratives and directionals

Taba has two systems which are both involved in marking deixis: the demonstrative and the directional systems. Although compared to other Austronesian languages[30] Taba is typologically unusual in that its grammar involves little morphology, this is not the case when it comes to demonstratives and directionals. Both of these systems involve root morphemes which can occur either on their own or with affixes, creating a large variety of meanings.[31]

Demonstratives

There are two demonstrative roots in Taba: ne, which expresses proximity to the speaker, and dia (or shortened form da), which expresses distance from the speaker. Each of these roots can be combined with a variety of morphemes to produce different nouns and pronouns, as follows:

| ne (≈ this) | dia/da (≈ that) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Distal | ||

| Root forms | ne | dia/da | |

| Demonstrative pronouns | sg. | ine | idia |

| pl. | sine | sidia | |

| Locative nouns | ane | adia | |

| Similative nouns | 'biasa' | tane | tadia |

| 'alus' | tadine | taddia | |

| hatadine | hatadia | ||

| 'kasar' | dodine | dodia | |

| (Bowden 2001) | |||

Note: the three different categories of similative nouns refer to the three different registers of Taba, which have been ascribed the following meanings: biasa ('normal'), alus ('fine/respectful') and kasar ('coarse').[31]

Root forms

Root forms ne and dia have a deictic function with respect to the speaker, and can express the speaker's physical, textural, temporal or even emotional and spiritual distance from something. These forms, when used on their own, occur immediately after the noun phrase to which they refer, much like the equivalent forms in many other Malayo-Polynesian languages.[32] Examples of the root forms functioning as such can be seen below:

pakakas

tool

ne

PROX

'this tool' (Bowden 2001, p. 88)

kurusi

chair

da

DIST

'that chair' (Bowden 2001, p.88)

Demonstrative root forms in Taba, like in most other languages, can also be used to refer to concepts previously mentioned in a conversation, as per the following example:[31]

Ndadi

ndadi

so

dukon

dukon

eruption

ne

ne

PROX

taun

taun

year

halim

ha=lim

CL=five

do.

do

REAL

'So the eruption was five years ago.' (Bowden 2001, p. 272)

Although the demonstrative roots are a closed class and most clearly mark deixis, they also belong to a slightly larger class of deictics, including the directional root ya ('up'). When this directional root is used deictically, it implies that both the speaker and hearer hold some common knowledge about the referent.[31] Directionals will be discussed in further detail in the next section. See below an example of ya functioning deictically:

Malcoma

m=alcoma

2sg=send

yak

yak

1sg

ni

ni

3sg.POSS

foto

foto

photograph

ya

ya

REC

'Send me the photographs (that I have just referred to, and which we both know about' (Bowden 2001, p. 273)

Demonstrative pronouns

Taba has four demonstrative pronouns, each formed through the affixation of a pronoun to the demonstrative root.[31] This process, as well as the rough English translation for each pronoun is outlined in the table below:

| ne | da/dia | |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Distal | |

| singular | ine i-ne SG-PROX 'this' (near speaker) |

ida i-da SG-DIST / / / idia i-dia SG-DIST 'that' (away from speaker) |

| plural | sine si-ne PL-PROX 'these' (near speaker) |

sida si-da PL-DIST / / / sidia si-dia PL-DIST 'those' (away from speaker) |

| (Bowden 2001, p. 273) | ||

Taba's demonstrative pronouns can also be used to refer to a concept previously mentioned in a conversation, or a series of previously described events, as shown in the next two examples:

Idia

i-dia

3SG-DIST

Minggu

Minggu

Sunday

'That was Sunday' (Bowden 2001, p. 275)

Lai

lai

just

tam

t=am

1PL.INCL=see

idia

i-dia

3SG-DIST

'We had just seen all of this (for the first time)' (Bowden 2001, p. 275)

Locative nouns

Taba has two locative nouns, formed by the prefixation of a-. The formation of these nouns and their rough English translations can be found in the table below:

| ne | dai/dia |

|---|---|

| Proximal | Distal |

ane a-ne LOC-PROX 'here' |

adia a-dia LOC-DIST 'there' |

| (Bowden 2001, p. 275) | |

Here are two examples showing the locative nouns in use, occurring after the noun to which they refer:

Si

Si

3PL

ane

a-ne

LOC-PROX

te

te

NEG

'He wasn't there' (Bowden 2001, p. 275)

Peda

peda

machete

adia

a-dia

LOC-DIST

loka

loka

banana

ni

ni

3SG.POSS

umpo

um-po

NOM-down

lema

le-ma

land-VEN

'The machete is there, landwards from the bottom of the banana tree' (Bowden 2001, p. 276)

Similative nouns

Taba has eight similative nouns, which differ between the language's three registers. Many other Austronesian languages have similative noun equivalents,[33] but Taba is unique in that it has such a high number. The eight different forms can be found in the table below, where the labels ascribed to each register by Taba speakers are as such: biasa ('normal'), alus ('fine/respectful') and kasar ('coarse').[31]

| ne | di/dia | |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Distal | |

| biasa | tane | tadia |

| alus | tadine | taddia |

| hatadine | hatadia | |

| kasar | dodine | dodia |

Below is an example of a similative noun occurring naturally in a conversation:

Napnap

yapyap

ash

um

um

house

ni

ni

3SG.POSS

llo

llo

inside

ya

ya

REC

mlongan

mlongan

be.long

tane

ta-ne

SIM-PROX

'The ash inside the house was as deep as this' (Bowden 2001, p. 94)

Similative nouns in Taba can also occur as single-word utterances and as adverbs,[31] as in the following examples:

Tadia!

ta-dia

SIM-DIST

'It's done like that!', 'I've done it!', 'Tadaa!' etc. (Bowden 2001, p. 276)

Tit

tit

1PL.INCL

tpe

t-pe

1PL.INCL.do

tane

ta-ne

SIM-PROX

'We do it like this' (Bowden 2001, p. 277)

Directionals

As for the directional system, Taba has five basic semantic categories. These, along with their roughly translated English equivalents are: ya ('up'), po ('down'), la ('sea'), le ('land') and no ('there'). Like demonstratives, directionals in Taba can be affixed to express more complex meanings, namely motion towards or from a direction, position in a direction, and parts of something that are oriented in a particular direction. This kind of morphology is unusual within Taba, but typologically common compared to many other Austronesian languages.[30][31] It is worth noting that while the directional roots in Taba can have rough English translations, utterances containing them will often have senseless meanings if translated directly into English.

All Taba directionals formed by affixation can be found in the table below. The essive forms refer to static location in a particular direction and the allative forms refer to motion towards a particular direction. The venitive forms refer to motion away from a particular direction and the nominalised forms refer to parts of something that are oriented in a particular direction.[31]

| Root | ya (up) | po (down) | la (sea) | le (land) | no (there) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESSive | yase | pope | lawe | lewe | noge |

| ALLative | attia | appo | akl | akla | akno |

| VENitive | yama | poma | lame | lema | noma |

| NOMinalised | tattubo | umpo | kla | kle | kno |

| (Bowden 2001) | |||||

Essive forms

Essive directionals in Taba, as stated above, signify static location in a particular direction. These forms can have a larger range of functions when compared with the other directionals. Namely, they can occur as verb adjuncts, both with a locative phrase and alone.[31] They can occur either before or after a verb, or to modify a noun phrase. Shown below is an example of the essive forms being used in a sentence:

Sama

Sama

same

lo

lo

as

John

John

John

nalusa

n=ha-lusa

3sg=CAUS-say

ni

ni

3sg.POSS

abu

abu

ash

nwom

n=wom

3sg=come

lawe

la-we

sea-ESS

'Just like you (John) said the ash (from the eruption) fell in Australia' (Bowden 2001, p. 290)

Allative forms

Allative directional forms in Taba express movement towards a particular direction. These forms can occur on their own, after the verb as an adjunct, or at the head of a locative phrase.[31] Examples of these two functions occurring in natural speech are shown below:

Ncopang

n=sopang

3SG=descend

akla

ak-la

ALL-sea

'It descended to the sea' (Bowden 2001, p. 288)

Malai

Malai

then

lhan

l=han

3PL=go

appo

ap-po

ALL-down

'Then they went downwards' (Bowden 2001, p. 288)

Venitive forms

Venitive directional forms in Taba express movement away from a particular direction. These forms are much freer in word order and can occur at many different places within a clause, serving to modify verbs, as seen in the next two examples:[31]

Noma

no-ma

there-VEN

noma

no-ma

there-VEN

turus

turus

direct

manusia

manusia

people

lwom

l=wom

3pl=come

'From here and there the people came' (Bowden 2001, p. 289)

Nyoa

n=yoa

3sg=search (almost)

khan

k=han

1sg=go

lama,

la-ma

sea-VEN

polisisi

polisi=si

police-PL

ltahan

l=tahan

3pl=find

yak

yak

1sg

'I'd almost come back from Moti when the police found me' (Bowden 2001, p. 94)

Venitive forms can also occur in utterances without any verbs, such as in the following example:

Motor

motor

boat

Payahe

Payahe

Payahe

lema

le-ma

land-VEN

yak

yak

1sg

'I came on the boat from Payahe' (Bowden 2001, p. 289)

The suffix -ma, used to form venitive directionals is likely derived from the word *maRi ('come'), that has been reconstructed for Proto-Austronesian.[31][34]

Nominalised forms

Nominalised directional forms in Taba signify parts of an object that are oriented towards a particular direction. These forms are always possessed by and occur after the noun relative to which the location is being expressed.[31] This is illustrated in the following two examples:

Kapal

Kapal

ship

ya

ya

REC

pso

p-so

CL-one

nuso

n=uso

3sg=follow

lawe

la-we

sea-ESS

Botan

Botan

Halmahera

ni

ni

3sg.POSS

umpo

um-po

NOM-down

lawe

la-we

sea-ESS

'There was a ship following along underneath Halmahera' (Bowden 2001, p. 287)

I

i

3sg

ntongo

n=tongo

3sg=stay

'Happy Restaurant'

'Happy Restaurant'

'Happy Restaurant'

ni

ni

3sg.POSS

kle

k-le

NOM-land

'He's staying landwards from the 'Happy Restaurant (Bowden 2001, p. 287)

List of glossing abbreviations

This section contains only the glossing abbreviations that appear in this article. For a full list, see List of glossing abbreviations.

| Gloss | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ADMON | admonitive mood |

| ALL | allative case |

| APPL | applicative voice |

| CAUS | causative |

| CL | classifier |

| CONT | continuous aspect |

| DEM | demonstrative |

| DETR | detransitivizer |

| DIST | distal demonstrative |

| ESS | essive case |

| FOC | focus |

| LOC | locative case |

| NEG | negation |

| NOM | nominative case |

| PL | plural |

| POSS | possessive marker |

| POT | potential mood |

| PROX | proximal demonstrative |

| REAL | realis mood |

| REC | reciprocal voice |

| REM | remote past tense |

| SG | singular |

| SIM | simultaneous aspect |

| VEN | venitive |

Name taboo (aroah)

As is common with many Melanesian people, Taba speakers practice ritual name taboo. As such, when a person dies in a Taba community, their name may not be used by any person with whom they had a close connection. This practice adheres to the Makianese belief that, if the names of the recently deceased are uttered, their spirits may be drastically disturbed. The deceased may be referred to simply as 'Deku's mother' or 'Dula's sister'. Others in the community with the same name as the deceased will be given maronga, or substitute names.[35]

Notes

- Taba at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Ethnologue: Makian, East

- Bowden 2001, p. 190

- Ethnologue: Makian, East

- Bowden 2001, p. 5

- Bowden 2001, p. 26

- Bowden 2001, p. 28

- Bowden 2001, p. 1

- Bowden 2001, p. 188

- Bowden 2001, p. 190

- Bowden 2001, p. 187

- Bowden 2001, p. 194

- Bowden 2001, p. 230

- Bowden 2001, p. 233

- Bowden 2001, p. 197

- Bowden 2001, p. 239

- Florey 2010, p. 246

- Bowden 2001, p. 335

- Florey 2010, p. 248; Reesink 2002, p. 246

- Bowden 2001, pp. 335-336

- Bowden 2001, p. 336

- Bowden 2001, pp. 337-339

- Bowden 2001, pp. 337-338

- Bowden 2001, p. 338

- Bowden 2001, pp. 338-339

- Bowden 2001, pp. 316-318

- Bowden 2001, p. 337

- Bowden 2001, p. 369

- Bowden 2001, p. 356

- "WALS Online - Feature 26A: Prefixing vs. Suffixing in Inflectional Morphology". wals.info. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- Bowden, John (2001). Taba: description of a South Halmahera language. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0858835177.

- "WALS Online - Feature 88A: Order of Demonstrative and Noun". wals.info. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- "WALS Online - Language Taba". wals.info. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- "Austronesian Comparative Dictionary - Words: a". www.trussel2.com. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- Bowden 2001, p. 22

References

- Bowden, John (2001). Taba: description of a South Halmahera language. Pacific Linguistics. Vol. 521. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. doi:10.15144/PL-521. ISBN 0858835177.

- Florey, Margaret (2010). "Negation in Moluccan languages". In Ewing, Michael C.; Klamer, Marian (eds.). East Nusantara: Typological and areal analyses. Vol. 618. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. pp. 227–250. doi:10.15144/PL-618 (inactive 1 August 2023). hdl:1885/146766. ISBN 9780858836105.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Reesink, Ger P. (2002). "Clause-final negation: structure and interpretation". Functions of Language. 9 (2): 239–268. doi:10.1075/fol.9.2.06ree.