Tapentadol

Tapentadol, brand names Nucynta among others, is a centrally acting opioid analgesic of the benzenoid class with a dual mode of action as an agonist of the μ-opioid receptor and as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI).[3] Analgesia occurs within 32 minutes of oral administration, and lasts for 4–6 hours.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nucynta, Palexia, Yantil, Tapenta, Tapal, Aspadol, others |

| Other names | BN-200 CG-5503 R-331333 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a610006 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 32% (oral)[3] |

| Protein binding | 20%[4] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (mostly via glucuronidation but also by CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hours< (duration 4-6 hours)[3] |

| Excretion | Urine and faeces (1%)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.131.247 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

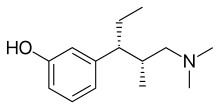

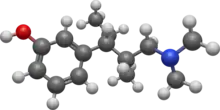

| Formula | C14H23NO |

| Molar mass | 221.344 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Boiling point | (decomposes) |

| |

| |

| | |

It is similar to tramadol in its dual mechanism of action; namely, its ability to activate the μ-opioid receptor and inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine.[5] Unlike tramadol, it has only weak effects on the reuptake of serotonin and is a significantly more potent opioid with no known active metabolites.[5][6] Tapentadol is not a pro-drug and therefore does not rely on metabolism to produce its therapeutic effects; this makes it a useful moderate-potency analgesic option for patients who do not respond adequately to more commonly used opioids due to genetic disposition (poor metabolizers of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6), as well as providing a more consistent dosage-response range among the patient population.

The potency of tapentadol is somewhere between that of tramadol and morphine,[7] with an analgesic efficacy comparable to that of oxycodone despite a lower incidence of side effects.[3] It is generally regarded as a moderately strong opioid. The CDC Opioid Guidelines Calculator estimates a conversation rate of 50mg of tapentadol equaling 20mg of oral morphine sulfate in terms of opioid receptor activation.[8]

Tapentadol was approved by the US FDA in November 2008,[9] by the TGA of Australia in December 2010[10] and by the MHRA of the UK in February 2011.[11] In India, Central Drug Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) approved tapentadol immediate-release (IR) preparations (50, 75 and 100 mg) for moderate to severe acute pain and extended-release (ER) preparations (50,100,150 and 200 mg) for severe acute pain in April 2011 and December 2013 respectively.[12]

Medical use

Tapentadol is used for the treatment of moderate to severe pain for both acute (following injury, surgery, etc.) and chronic musculoskeletal pain. It is also specifically indicated for controlling the pain of diabetic neuropathy when around-the-clock opioid medication is required. Extended-release formulations of tapentadol are not indicated for use in the management of acute pain.[3][13][14]

Tapentadol is Pregnancy Category C. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies of tapentadol in pregnant women, and tapentadol is not recommended for use in women during and immediately prior to labor and delivery.[14]

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies of tapentadol in children.[14]

Contraindications

Tapentadol is contraindicated in people with epilepsy or who are otherwise prone to seizures. It raises intracranial pressure so should not be used in people with head injuries, brain tumors, or other conditions which increase intracranial pressure. It increases the risk of respiratory depression so should not be used in people with asthma. As with other μ-opioid agonists, tapentadol may cause spasms of the sphincter of Oddi, and is therefore discouraged for use in patients with biliary tract disease such as both acute and chronic pancreatitis. People who are rapid or ultra rapid metabolizers for the CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 enzymes may not respond adequately to tapentadol therapy. Due to reduced clearance, tapentadol should be administered with caution to people with moderate liver disease and not at all in people with severe liver disease.[14]

Adverse effects

The most commonly reported side effects of tapentadol therapy in clinical trials were nausea, vomiting, dizziness, sleepiness, itchiness, dry mouth, headache, and fatigue.[3]

According to the World Health Organization there is little evidence to judge the abuse potential of tapentadol.[15] Although early pre-clinical animal trials suggested that tapentadol has a reduced abuse liability compared to other opioid analgesics[3] the US DEA placed tapentadol into Schedule II,[16] the same category as stronger opioids more commonly used recreationally, such as morphine, Oxycodone, and fentanyl.[14][17]

Tapentadol has been demonstrated to reduce the seizure threshold in patients. Tapentadol should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures, and in patients who are also taking one or more other drugs which have also been demonstrated to reduce the seizure threshold. Patients at high risk include those using other serotogenic and adrenergic medications, as well as patients with head trauma, metabolic disorders, and those in alcohol and/or drug withdrawals.[18]

Tapentadol has been demonstrated to potentially produce hypotension (low blood pressure), and should be used with caution in patients with low blood pressure, and patients who are taking one or more other medications which are also known to reduce blood pressure.[18]

Interactions

Combination with SSRIs, SNRIs, SRAs, and serotonin receptor agonists may lead to potentially lethal serotonin syndrome.[19] Combination with MAOIs may also result in an adrenergic storm. Use of tapentadol with alcohol or other sedatives such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, nonbenzodiazepines, phenothiazines, and other opiates may result in increased impairment, sedation, respiratory depression, and death.[3] Tapentadol is partially metabolized by the hepatic enzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 so it innately has interactions with drugs that enhance or repress the activity/expression of one or more of these enzymes, as well as with substrates of these enzymes (due to competition for the enzyme); some enzyme mediators/substrates require dosing adjustments to one or both medications.[3]

The combination of tapentadol and alcohol may result in increased plasma concentrations of tapentadol and produce respiratory depression to a degree greater than the sum of the two drugs when administered separately; patients should be cautioned against alcohol consumption when taking tapentadol as the combination may be fatal.[18]

Tapentadol should be used with caution in patients who are taking one or more anticholinergic drugs, as this combination may result in urine retention (which can result in serious renal damage and is considered a medical emergency).[18]

Pharmacology

Tapentadol is an agonist of the μ-opioid receptor and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI).[3] Analgesia occurs within 32 minutes after oral administration, and lasts for 4–6 hours.[5] It is 18 times less potent than morphine in terms of binding to human μ-opioid receptors in in vitro research on human tissue.[20] In vivo, only 32% of an oral dose of tapentadol will survive first pass metabolism and proceed to the bloodstream to produce its effects on the central and peripheral nervous systems of the patient.[3]

It is similar to tramadol in its dual mechanism of action but unlike tramadol, it has much weaker effects on the reuptake of serotonin and is a significantly more potent opioid (around 2-3 times stronger) with no known active metabolites.[5][6][21]

Commercial preparations contain only the (R,R) stereoisomer, which is the weakest isomer in terms of opioid activity.[15] The free base conversion ratio for salts includes 0.86 for the hydrochloride.[22]

The peak plasma concentration (Cmax; amount of active drug in the bloodstream) when taken after eating is increased by 8% and 18% for tapentadol IR and ER preparations, respectively. This difference is not clinically significant, tapentadol may therefore be administered orally with or without food as circumstances allow, and the patient will generally not notice any change in the efficacy and/or duration of analgesic effects if the drug is not consistently administered in fasting or fed states (patients will receive the same benefits from their dose regardless of what and when they last ate). The plasma concentration of tapentadol differs to a relevant degree based on the administered dose, with the highest tested dose (250 mg) resulting in a higher Cmax than would be expected via the dose-proportionate plasma concentration expectations.[18] Increased doses of tapentadol should be anticipated to be slightly stronger than predicted by linear functions of the previous dose-response relation.

History

Tapentadol was invented at the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal in the late 1980s led by Helmut Buschmann;[23] the team started by analyzing the chemistry and activity of tramadol, which had been invented at the same company in 1962.[24]: 302 Tramadol has several enantiomers, and each forms metabolites after processing in the liver. These tramadol variants have varying activities at the μ-opioid receptor, the norepinephrine transporter, and the serotonin transporter, and differing half-lives, with the metabolites having the best activity. Using tramadol as a starting point, the team aimed to discover a single molecule that minimized the serotonin activity, had strong μ-opioid receptor agonism and strong norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, and would not require metabolism to be active; the result was tapentadol.[24]: 301–302

In 2003 Grünenthal partnered with two Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development and Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical to develop and market tapentadol; Johnson & Johnson had exclusive rights to sell the drug in the US, Canada, and Japan while Grünenthal retained rights elsewhere.[25]: 143 In 2008 tapentadol received FDA approval; in 2009 it was classified by DEA as a Schedule II drug, and entered the US market.[25]: 143 Tapentadol was reported to be the "first new molecular entity of oral centrally acting analgesics" class approved in the United States in more than 25 years.[26]

In 2010 Grünenthal granted Johnson & Johnson the right to market tapentadol in about 80 additional countries.[27] Later that year, tapentadol was approved in Europe.[28] In 2011, Nucynta ER, an extended release formulation of tapentadol, was released in the United States for management of moderate to severe chronic pain and received FDA approval the following year for the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.[29][30]

After annual sales of $166 million, in January 2015, Johnson & Johnson sold its rights to market tapentadol in the US to Depomed for $1 billion.[31] The drug was manufactured at a plant located on the island of Puerto Rico that was hit by Hurricane Maria in 2017 causing a major shortage in the drug's availability.[32] In January 2018 Depomed sold off the manufacturing of the drug and licensed it to Collegium Pharmaceutical for $10 million up front with an annual royalty payment of a minimum $135 million for the next 4 years.[33] This combination of events has caused additional short supply of the drug leaving patients who depend on it to seek alternative treatments.

Abuse and controls

.jpg.webp)

There have been calls for Tapentadol to be only marketed in countries where appropriate controls exist,[34] but after performing a critical review, the United Nations Expert Committee on Drug Dependence in 2014 advised that tapentadol not be placed under international control but remain under surveillance.[35]

Since 2009 the drug has been categorized in the US as a Schedule II narcotic with ACSCN 9780; in 2014 it was allocated a 17,500 kg aggregate manufacturing quota.

In 2010, Australia made tapentadol an S8 controlled drug.[36] The following year, tapentadol was classified as a Class A controlled drug in the United Kingdom, and was also placed under national control in Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Latvia and Spain.[37][38]

More recently, Canada made the opioid a Schedule I controlled drug, putting it in the same class as other prescription opioids such as morphine, fentanyl, tramadol, and heroin.[39]

In India (except the state of Punjab), multiple brands of Tapentadol remain available over the counter. Recent reports have suggested increasing Tapentadol abuse and dependence in India, where users have improvised injections with 50 and 100 mg tablets.[12] Furthermore, a large number of listings for Tapentadol sourced from India can be found internationally on illicit marketplaces on the dark web. There have been several reports of Tapentadol from Indian pharmacies being smuggled to the US, the EU, and Bangladesh, where they are distributed via the black market.[40]

References

- Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Active substance(s): tapentadol" (PDF). List of nationally authorised medicinal products. European Medicines Agency. 21 July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-06. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- Smit JW, Oh C, Rengelshausen J, Terlinden R, Ravenstijn PG, Wang SS, et al. (January 2010). "Effects of acetaminophen, naproxen, and acetylsalicylic acid on tapentadol pharmacokinetics: results of two randomized, open-label, crossover, drug-drug interaction studies". Pharmacotherapy. 30 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1592/phco.30.1.25. PMC 2888545. PMID 20030470.

- Brayfield A, ed. (14 November 2011). "Tapentadol". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Singh DR, Nag K, Shetti AN, Krishnaveni N (July 2013). "Tapentadol hydrochloride: A novel analgesic". Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. 7 (3): 322–326. doi:10.4103/1658-354X.115319. PMC 3757808. PMID 24015138.

- Raffa RB, Buschmann H, Christoph T, Eichenbaum G, Englberger W, Flores CM, et al. (July 2012). "Mechanistic and functional differentiation of tapentadol and tramadol". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (10): 1437–1449. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.696097. PMID 22698264. S2CID 24226747.

- Tschentke TM, De Vry J, Terlinden R, Hennies HH, Lange C, Strassburger W, et al. (2006). "Tapentadol Hydrochloride". Drugs of the Future. 31 (12): 1053. doi:10.1358/dof.2006.031.12.1047744.

- "CDC Opioid Calculator". 13 October 2022.

- "Nucynta History". drugs.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- "PALEXIA® SR PRODUCT INFORMATION" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. CSL Limited. 26 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Palexia film coated tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. Grunenthal Ltd. 13 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Mukherjee D, Shukla L, Saha P, Mahadevan J, Kandasamy A, Chand P, et al. (March 2020). "Tapentadol abuse and dependence in India". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 49: 101978. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101978. PMID 32120298. S2CID 211834859. Archived from the original on 2021-12-20. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- "Medscape-Nucynta". Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- "Nucynta Label" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-30.

- 35th Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Hammamet, Tunisia (June 2012). "Tapentadol: Expert peer review on pre-review report" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Leonhart MM, Deputy Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration (May 2009). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Tapentadol Into Schedule II". Federal Register. 74 (97): 23790–93.

- "DEA Diversion Control – Controlled Substances Schedules". US Federal Government. Archived from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- Janssen Inc. "NUCYNTA® CR" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- Nossaman VE, Ramadhyani U, Kadowitz PJ, Nossaman BD (December 2010). "Advances in perioperative pain management: use of medications with dual analgesic mechanisms, tramadol & tapentadol". Anesthesiology Clinics. 28 (4): 647–666. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2010.08.009. PMID 21074743.

- "Tapentadol". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Roulet L, Rollason V, Desmeules J, Piguet V (July 2021). "Tapentadol Versus Tramadol: A Narrative and Comparative Review of Their Pharmacological, Efficacy and Safety Profiles in Adult Patients". Drugs. 81 (11): 1257–1272. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01515-z. PMC 8318929. PMID 34196947.

- "2014 - Final Adjusted Aggregate Production Quotas for Schedule I and II Controlled Substances and Assessment of Annual Needs for the List I Chemicals Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine for 2014". Deadiversion.usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- US 6248737, "1-phenyl-3-dimethylaminopropane compounds with a pharmacological effects"

- Helmut Buschmann. Tapentadol – From Morphine and Tramadol to the Discovery of Tapentadol. Chapter 12 in Analogue-based Drug Discovery III, First Edition. Edited by Janos Fischer, C. Robin Ganellin, and David P. Rotella. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. 2013. ISBN 9783527651108

- Dan Froicu and Raymond S Sinatra. Tapentadol. Chapter 31 in The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics, Eds. Raymond S. Sinatra, Jonathan S. Jahr, J. Michael Watkins-Pitchford. Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 9781139491983

- "Grünenthal GmbH Presents Tapentadol, a Novel Centrally Acting Analgesic, at the 25th Annual Scientific Meeting of The American Pain Society". PR Newswire. 6 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- "Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V. Announces Expansion of Licensing Agreement for Tapentadol". J&J Press Release. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2018-09-23.

- Dutton G (1 June 2012). "Pain Management Market Ripe with Immediate Opportunities". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Archived from the original on 2018-09-23.

- "Nucynta (tapentadol) FDA Approval History – Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-12. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- "FDA Approves Nucynta ER (tapentadol) Extended-Release Oral Tablets for the Management of Neuropathic Pain Associated With Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy". Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- Staff (16 January 2015). "Depomed pays over $1 billion for US rights to Janssen's Nucynta franchise". The Pharma Letter. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08.

- Byrne M, Pallaria F. "Dealing with Prescription Drug Shortages". www.iwpharmacy.com. Archived from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Troubled Depomed sells off Nucynta, axes 40% of workforce to pare down costs". FiercePharma. 5 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Supplemental data for World Health Organization (Expert Committee on Drug Dependence) Critical Review on drug dependence of tapentadol" (PDF). World Health Organization. 23 May 2014. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "World Health Organization: Reports of advisory bodies" (PDF). World Health Organization. 22 January 2015. pp. 2, 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Australian Public Assessment Report for Tapentadol" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2011". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- "International Narcotics Control Board Report 2012" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. 5 March 2013. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Canada Gazette – Regulations Amending the Narcotic Control Regulations (Tapentadol) – (Archived)". Canada Gazette. Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Integrated Services Branch, Canada. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- "71 arrested in DMP's anti-narcotics drive". BanglaNews24.com (in Bengali). 2021-12-14. Archived from the original on 2021-12-30. Retrieved 2021-12-30.