Carbomycin

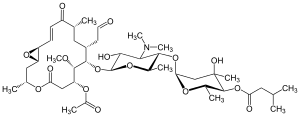

Carbomycin, also known as magnamycin, is a colorless, optically active crystalline[1] macrolide antibiotic with the molecular formula C42H67NO16. It is derived from the bacterium Streptomyces halstedii and active in inhibiting the growth of Gram-positive bacteria and "certain Mycoplasma strains."[2] Its structure was first proposed by Robert Woodward in 1957 and was subsequently corrected in 1965.[3]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(2S,3S,4R,6S)-6-{[(2R,3S,4R,5R,6S)-6-{[(1S,3R,7R,8S,9S,10R,12R,14E,16S)-7-(Acetyloxy)-8-methoxy-3,12-dimethyl-5,13-dioxo-10-(2-oxoethyl)-4,17-dioxabicyclo[14.1.0]heptadec-14-en-9-yl]oxy}-4-(dimethylamino)-5-hydroxy-2-methyloxan-2-yl]oxy}-4-hydroxy-2,4-dimethyloxan-3-yl 3-methylbutanoate | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C42H67NO16 |

| Molar mass | 841.97848 |

| Density | 1.24g/ cm3 |

| Melting point | 214℃ (417.2°F) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.2 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Synthesis

The discovery of carbomycin was first reported by Fred W. Tanner Jr. of Pfizer.[4] Carbomycin can be isolated from Streptomyces halstedii via extraction from a fermentation broth and purified through crystallization from alcohol-water mixtures.[1] Carbomycin can be further purified with the use of preparative thin-layer chromatography. The most efficient solvent is one consisting of ethanol-hexane-water in 90-10-0.15 volume ratio.[5]

In the biosynthesis of carbomycin by Streptomyces halstedii, when soybean meal is used to ferment the antibiotic, the addition of several substances can increase the yield of carbomycin. When blackstrap molasses, a carbon source, is added, an increased yield is observed. Nitrogen sources ammonium chloride, ammonium nitrate, and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate have the same effect on the production of carbomycin. The addition of the organic salts sodium acetate and sodium tartrate also increases the yield of the antibiotic.[6]

Studies of the chemical degradation of carbomycin and comparison of molar activities of propionate-labeled carbomycins and their degradation products suggest that the biosynthesis of carbomycin by Streptomyces halstedii include the synthesis of the lactone backbone from eight acetate units and one propionate unit with the branching methyl group deriving from C-3 of propionate.[7]

Medical use

As carbomycin is not a strong antibiotic, it is not used extensively and is considered a minor antibiotic; it is most effective when used in combination with other drugs.[8] The range of activity of carbomycin is similar to that of erythromycin. In testing the response of 74 strains of bacteria, their susceptibility across carbomycin and erythromycin was consistent. However, a higher concentration of carbomycin is needed to achieve the same effect as that of erythromycin.[9] The effectiveness of carbomycin as an antibiotic varies. When used to treat 45 patients with pneumonia, carbomycin was as effective as other antibiotics for six patients. Two developed meningitis, while, for twelve patients, it was necessary that the use of carbomycin in treatment be replaced with penicillin.[9] Carbomycin has been successful in treating neither staphylococcal sepsis nor bacterial endocarditis.[9] In 1954, carbomycin was found to be an effective treatment for granuloma inguinale by Harry M. Robinson and Morris M. Cohen.[10] However, complete healing from the condition depends on the severity and duration of the condition. There were no adverse reactions found to be associated with the use of carbomycin.

Mode of action

Carbomycin stimulates the "accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA in cells at the nonpermissive temperature" of 40˚C in E. coli and thereby inhibits protein synthesis. Carbomycin is able to inhibit protein synthesis by stimulating the dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA from the ribosome, inhibiting the nascent peptide chain from passing through the exit tunnel and out of the ribosome.[11]

References

- Wagner, Richard L.; F.A. Hochstein; Kotaro Murai; N. Messina; Peter P. Regna (1953). "Magnamycin. A new Antibiotic". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75 (19): 4684–87. doi:10.1021/ja01115a019.

- Ziegler, F. E.; Gilligan, P. J. (1981). "Synthetic Studies on the Carbomycins (Magnamycins): An Exception to the Enantioselective Synthesis of Beta-Alkyl Carboxylic Acids via Chiral Oxazolines". J. Org. Chem. 46 (19): 3874–80. doi:10.1021/jo00332a023.

- Woodward, R. B.; Weiler, L. S.; Dutta, P. C. (1965). "The Structure of Magnamycin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87 (20): 4662–63. doi:10.1021/ja00948a058. PMID 5845078.

- "Carbomycin". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4851): 1421–22. 26 December 1953. JSTOR 20313504.

- Baghlaf, A.O.; A.Z.A Abou-Zeid; A.I. El-Diwzny (1981). "Biosynthesis of Carbomycin, its Extraction, Purification and Mode of Action on Bacillus subtilis". Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 31 (1): 241–46. doi:10.1002/jctb.503310133.

- Ghonaim, S.A.; A.M. Khalil; A.A. Abou-Zeid (March 1980). "Factors affecting fermentative production of magnamycin by Streptomyces halsted II". Agricultural Wastes. 2 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1016/0141-4607(80)90044-X.

- Srinivasan, Dorothy; P.R. Srinivasan (1967). "Studies on the Biosynthesis of Magnamycin". Biochemistry. 6 (10): 3111–18. doi:10.1021/bi00862a019. PMID 6056977.

- Welch, Henry (1960). The Antibiotic Saga. New York: The University of Michigan. pp. 88, 96.

- Kirk, J E; Effersøe, H (1953). "The Effect of Washing with Soap and with a Detergent on the 4-Hour Sebaceous Secretion in the Forehead12". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4851): 1421–22. doi:10.1038/jid.1954.34. PMID 13152393.

- Robinson, Harry M.; Cohen, MM (1954). "Magnamycin in the Treatment of Granuloma Inguinale". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 22 (4): 263–4. doi:10.1038/jid.1954.36. PMID 13152395.

- Menninger, J.R.; D.P. Otto (1982). "Erythromycin, carbomycin, and spiramycin inhibit protein synthesis by stimulating the dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA from ribosomes". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 21 (5): 811–18. doi:10.1128/AAC.21.5.811. PMC 182017. PMID 6179465.