Budd–Chiari syndrome

Budd–Chiari syndrome is a very rare condition, affecting one in a million adults.[1] The condition is caused by occlusion of the hepatic veins that drain the liver. It presents with the classical triad of abdominal pain, ascites, and liver enlargement. The formation of a blood clot within the hepatic veins can lead to Budd–Chiari syndrome. The syndrome can be fulminant, acute, chronic, or asymptomatic. Subacute presentation is the most common form.

| Budd–Chiari syndrome | |

|---|---|

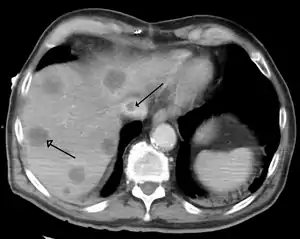

| |

| Budd–Chiari syndrome secondary to cancer, note clot in the inferior vena cava and the metastasis in the liver | |

| Specialty | Hepatology |

| Complications | Liver failure |

| Treatment | Anticoagulant medication, Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, Liver transplantation |

Signs and symptoms

The acute syndrome presents with rapidly progressive severe upper abdominal pain, yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes, liver enlargement, enlargement of the spleen, fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity, elevated liver enzymes, and eventually encephalopathy. The fulminant syndrome presents early with encephalopathy and ascites. Liver cell death and severe lactic acidosis may be present as well. Caudate lobe enlargement is often present. The majority of patients have a slower-onset form of Budd–Chiari syndrome. This can be painless. A system of venous collaterals may form around the occlusion which may be seen on imaging as a "spider's web". Patients may progress to cirrhosis and show the signs of liver failure.[2]

On the other hand, incidental finding of a silent, asymptomatic form may not be a cause for concern.[2]

Causes

The cause can be found in more than 80% of patients.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- Primary Budd–Chiari syndrome (75%): thrombosis of the hepatic vein

- Hepatic vein thrombosis is associated with the following in decreasing order of frequency:

- Polycythemia vera

- Pregnancy

- Postpartum state

- Use of oral contraceptives

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Lupus anticoagulants

- Secondary Budd–Chiari syndrome (25%): compression of the hepatic vein by an outside structure (e.g. a tumor)

Budd–Chiari syndrome is also seen in tuberculosis, congenital venous webs and occasionally in inferior vena caval stenosis.

Often, the patient is known to have a tendency towards thrombosis, although Budd–Chiari syndrome can also be the first symptom of such a tendency. Examples of genetic tendencies include protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, the Factor V Leiden mutation, hereditary anti-thrombin deficiency and prothrombin mutation G20210A.[11] An important non-genetic risk factor is the use of estrogen-containing (combined) forms of hormonal contraception. Other risk factors include the antiphospholipid syndrome, aspergillosis, Behçet's disease, dacarbazine, pregnancy, and trauma.[12]

Many patients have Budd–Chiari syndrome as a complication of polycythemia vera (myeloproliferative disease of red blood cells).[13] People who have paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) appear to be especially at risk for Budd–Chiari syndrome, more than other forms of thrombophilia: up to 39% develop venous thromboses,[14] and 12% may acquire Budd-Chiari.[15]

A related condition is veno-occlusive disease, which occurs in recipients of bone marrow transplants as a complication of their medication. Although its mechanism is similar, it is not considered a form of Budd–Chiari syndrome.

Other toxicologic causes of veno-occlusive disease include plant & herbal sources of pyrrolizidine alkaloids such as Borage, Boneset, Coltsfoot, T'u-san-chi, Comfrey, Heliotrope (sunflower seeds), Gordolobo, Germander, and Chaparral.

Pathophysiology

Any obstruction of the venous vasculature of the liver is referred to as Budd–Chiari syndrome, from the venules to the right atrium. This leads to increased portal vein and hepatic sinusoid pressures as the blood flow stagnates. The increased portal pressure causes increased filtration of vascular fluid with the formation of ascites in the abdomen and collateral venous flow through alternative veins leading to esophageal, gastric and rectal varices. Obstruction also causes centrilobular necrosis and peripheral lobule fatty change due to ischemia. If this condition persists chronically what is known as nutmeg liver will develop. Kidney failure may occur, perhaps due to the body sensing an "underfill" state and subsequent activation of the renin-angiotensin pathways and excess sodium retention.[16]

Diagnosis

When Budd–Chiari syndrome is suspected, measurements are made of liver enzyme levels and other organ markers (creatinine, urea, electrolytes, LDH).

Budd–Chiari syndrome is most commonly diagnosed using ultrasound studies of the abdomen and retrograde angiography. Ultrasound may show obliteration of hepatic veins, thrombosis or stenosis, spiderweb vessels, large collateral vessels, or a hyperechoic cord replacing a normal vein. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sometimes employed although these methods are generally not as sensitive. Liver biopsy is nonspecific but sometimes necessary to differentiate between Budd–Chiari syndrome and other causes of hepatomegaly and ascites, such as galactosemia or Reye's syndrome. Evaluation for a JAK2 V617F mutation is recommended.

Treatment

A minority of patients can be treated medically with sodium restriction, diuretics to control ascites, anticoagulants such as heparin and warfarin, and general symptomatic management. However, the majority of patients require further intervention. Milder forms of Budd–Chiari may be treated with surgical shunts to divert blood flow around the obstruction or the liver itself. Shunts must be placed early after diagnosis for best results.[17] The TIPS is similar to a surgical shunt: it accomplishes the same goal but has a lower procedure-related mortality, a factor that has led to a growth in its popularity. If all the hepatic veins are blocked, the portal vein can be approached via the intrahepatic part of inferior vena cava, a procedure called DIPS (direct intrahepatic portocaval shunt). Patients with stenosis or vena caval obstruction may benefit from angioplasty.[18] Limited studies on thrombolysis with direct infusion of urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator into the obstructed vein have shown moderate success in treating Budd–Chiari syndrome; however, it is not routinely attempted.

Liver transplantation is an effective treatment for Budd–Chiari. It is generally reserved for patients with fulminant liver failure, failure of shunts, or progression of cirrhosis that reduces the life expectancy to one year.[19] Long-term survival after a transplant ranges from 69 to 87%. The most common complications of transplants are rejection, arterial or venous thromboses, and bleeding due to the need for anticoagulants. Up to 10% of patients may have a recurrence of Budd–Chiari syndrome after the transplant.

Prognosis

Several studies have attempted to predict the survival of patients with Budd–Chiari syndrome. In general, nearly 2/3 of patients with Budd–Chiari are alive at 10 years. [17] Important negative prognostic indicators include ascites, encephalopathy, elevated Child-Pugh scores, elevated prothrombin time, and altered serum levels of various substances (sodium, creatinine, albumin, and bilirubin). Survival is also highly dependent on the underlying cause of the Budd–Chiari syndrome. For example, a patient with an underlying myeloproliferative disorder may progress to acute leukemia, independently of Budd–Chiari syndrome.[20]

Eponym

It is named after George Budd,[21][22] a British physician, and Hans Chiari,[23] an Austrian pathologist.

References

- Rajani R, Melin T, Björnsson E, Broomé U, Sangfelt P, Danielsson A, Gustavsson A, Grip O, Svensson H, Lööf L, Wallerstedt S, Almer SH (Feb 2009). "Budd–Chiari syndrome in Sweden: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and survival - an 18-year experience". Liver International. 29 (2): 253–9. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01838.x. PMID 18694401. S2CID 36353033. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- "Ascites". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd–Chiari syndrome".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd–Chiari syndrome)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The Budd–Chiari syndrome: a review".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Budd–Chiari syndrome: long-term survival and factors affecting mortality".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Budd–Chiari Syndrome: clinical patterns and therapy".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Budd–Chiari syndrome: etiology, diagnosis and management".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 51-1987. Progressive abdominal distention in a 51-year-old woman with polycythemia vera".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Hepatic outflow obstruction (Budd–Chiari syndrome). Experience with 177 patients and a review of the literature".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Podnos YD, Cooke J, Ginther G, Ping J, Chapman D, Newman RS, Imagawa DK (Aug 2003). "Prothrombin Mutation G20210A as a Cause of Budd–Chiari Syndrome" (PDF). Hospital Physician. 39 (8): 41–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- "Budd-Chiari Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Patel RK, Lea NC, Heneghan MA, et al. (Jun 2006). "Prevalence of the activating JAK2 tyrosine kinase mutation V617F in the Budd–Chiari syndrome". Gastroenterology. 130 (7): 2031–8. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.008. PMID 16762626.

- Hillmen P, Lewis SM, Bessler M, Luzzatto L, Dacie JV (Nov 1995). "Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria". N Engl J Med. 333 (19): 1253–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511093331904. PMID 7566002.

- Socié G, Mary JY, de Gramont A, et al. (Aug 1996). "Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria: long-term follow-up and prognostic factors. French Society of Haematology". Lancet. 348 (9027): 573–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)12360-1. PMID 8774569. S2CID 23456850.

- Aydinli, M; Bayraktar, Y (21 May 2007). "Budd-Chiari syndrome: Etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (19): 2693–2696. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i19.2693. PMC 4147117. PMID 17569137.

- Murad SD, Valla DC, de Groen PC, et al. (Feb 2004). "Determinants of survival and the effect of portosystemic shunting in patients with Budd–Chiari syndrome" (PDF). Hepatology. 39 (2): 500–8. doi:10.1002/hep.20064. hdl:1887/5096. PMID 14768004. S2CID 20101090.

- Fisher NC, McCafferty I, Dolapci M, et al. (Apr 1999). "Managing Budd–Chiari syndrome: a retrospective review of percutaneous hepatic vein angioplasty and surgical shunting". Gut. 44 (4): 568–74. doi:10.1136/gut.44.4.568. PMC 1727471. PMID 10075967.

- Orloff MJ, Daily PO, Orloff SL, Girard B, Orloff MS (Sep 2000). "A 27-year experience with surgical treatment of Budd–Chiari syndrome". Ann. Surg. 232 (3): 340–52. doi:10.1097/00000658-200009000-00006. PMC 1421148. PMID 10973384.

- "Ascites". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Budd–Chiari syndrome at Who Named It?

- Budd G (1845). On diseases of the liver. London: John Churchill. p. 135. Brit Lib. 000518193.

- Chiari H (1898). "Erfahrungen über Infarktbildungen in der Leber des Menschen". Zeitschrift für Heilkunde, Prague. 19: 475–512.