Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid

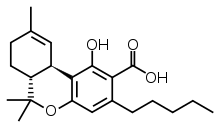

Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA, 2-COOH-THC; conjugate base tetrahydrocannabinolate) is a precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), an active component of cannabis.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 2-Carboxy-THC; THCA, 2-COOH-THC |

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.216.805 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H30O4 |

| Molar mass | 358.478 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

THCA is found in variable quantities in fresh, undried cannabis, but is progressively decarboxylated to THC with drying, and especially under intense heating such as when cannabis is smoked or cooked into cannabis edibles.[1] THCA is often the majority constituent in cannabis resin concentrates, such as hashish and hash oil, when prepared from high-THC cannabis fresh plant material, frequently comprising between 50% and 90% by weight.

Uses

THCA is rarely directly used, but its presence is commonly analyzed when cannabis or hemp-based products are screened for THC; some countries require that it be measured in such screens.[2][3]: 32

THCA in its isolated form is available for purchase in select medical and recreational cannabis dispensaries in the form of a white crystalline powder. It can be smoked or vaporized in typical smoking devices, such as a bong or dab rig (device used for vaporizing hash oil). These methods convert the THCA to THC and so are used for their psychoactive benefits. THCA is also sometimes encapsulated and taken as a supplement for a variety of illnesses, although there are currently no established medical applications.[4]

Pharmacological effects

Conversion of THCA to THC in vivo appears to be very limited, giving it only very slight efficacy as a prodrug for THC.[1] In receptor binding assays it is promiscuous;[5] there are papers showing it being an inhibitor of PC-PLC, COX-1, COX-2, TRPM8, TRPV1, FAAH, NAAA, MGL, and DGLα, and an inhibitor of anandamide transport, as well as an agonist of TRPA1 and TRPV2.[1] Many THCA reagents used in biochemistry experiments are contaminated with THC due to THCA's instability.[5]

A study found THCA and unheated Cannabis sativa extracts exert immuno-modulating effect, not mediated by the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways like THC. THCA were able to inhibit the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) levels in U937 macrophages and peripheral blood macrophages, an inhibition that persisted over a longer period of time, whereas after prolonged exposure time THC and heated extract tend to induce the TNF-alpha level. THCA and THC show distinct effects on phosphatidylcholine specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC) activity, as THCA and unheated extracts inhibit the PC-PLC activity in a dose-dependent manner, but THC only induced PC-PLC activity at high concentrations, suggest THCA and THC exert their immuno-modulating effects via different metabolic pathways.[6]

The anti-inflammatory activity of C. sativa extracts was studied on three lines of epithelial cells and on colon tissue in a model of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), where C. sativa flowers were extracted with ethanol, found the anti-inflammatory activity of Cannabis extracts derives from THCA present in fraction 7 (F7) of the extract. However, all fractions of C. sativa at a certain combination of concentrations show a significant increased cytotoxic activity and suppress COX-2 and MMP9 gene expression in both cell culture and colon tissue, suggest the anti-inflammatory activity of Cannabis extracts on colon epithelial cells derives from a fraction of the extract that contains THCA, and is mediated, at least partially, via GPR55 receptor. The cytotoxic activity of the C. sativa extract was increased by combining all fractions at a certain combination of concentrations and was partially affected by CB2 receptor antagonist that increased cell proliferation. It is suggested that in a nonpsychoactive treatment for IBD, THCA should be used rather than CBD.[7]

THCA binds to and activates PPARγ with higher potency than its decarboxylated products.[8]

THCA show a similar metabolism as THC in humans, producing 11-OH-THCA and 11-nor-9-carboxy-THCA.[9] Although the decarboxylation of THCA to THC was assumed to be complete, which means that no THCA should be detectable in urine and blood serum of cannabis consumers, it is found in the urine and blood serum samples collected from police controls of drivers, suspected for driving under the influence of drugs (DUID). THCA was detected in the urine and blood serum samples of several cannabis consumers in concentrations of up to 10.8 ng/ml in urine and 14.8 ng/ml in serum. The concentration of THCA was below the THC concentration in most serum samples, resulting in molar ratios of THCA/THC of approximately 5.0–18.6%. Where a short elapsed time between the last intake and blood sampling was assumed, the molar ratio was 18.6% in the serum.[10]

Chemistry

It has two isomers, THCA-A, in which the carboxylic acid group is in the 1 position, between the hydroxy group and the carbon chain, and THCA-B, in which the carboxylic acid group is in the 3 position, following the carbon chain.[11]: 20 The crystal structures of both THCA-A (colourless prisms, orthorhombic P212121) and THCA-B (also colourless prisms, orthorhombic P212121) have been reported.[12][13]

In the past THCA was thought to be formed in plants by cyclization of cannabidiolic acid but due to studies in the late 1990s it became apparent that its precursor is cannabigerolic acid, which goes through oxidocyclization through the actions of the enzyme THCA-synthase.[3]: 14

It is unstable, and slowly decarboxylates into THC during storage, and the THC itself slowly degrades to CBN, found with potential immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory activities.[1] When heated or burned, as when cannabis is smoked or included in baked goods, the decarboxylation is rapid but not complete; THCA is detectable in people who smoke or otherwise consume cannabis.[1]

Legal status

THCA is not scheduled by the United Nations' Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[14]

United States

THCA is not scheduled at the federal level in the United States,[15] but it is possible that THCA could legally be considered an analog of THC and sales or possession could potentially be prosecuted under the Federal Analogue Act.[16] In practice, because THCA spontaneously decarboxylates to form THC, no real sample of purified THCA will be completely free of THC. Thus, any laboratory analysis of THCA using any technique involving significant heat will generate THC in the handling and analytical process.

See also

- Cannabinoids

- Cannabidiol (CBD)

- Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

References

- Moreno-Sanz, G (2016). "Can You Pass the Acid Test? Critical Review and Novel Therapeutic Perspectives of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid A." Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 1 (1): 124–130. doi:10.1089/can.2016.0008. PMC 5549534. PMID 28861488.

- Dussy FE, Hamberg C, Luginbühl M, Schwerzmann T, Briellmann TA (2005-04-20), "Isolation of Delta9-THCA-A from hemp and analytical aspects concerning the determination of Delta9-THC in cannabis products", Forensic Science International, 149 (1): 3–10, doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.05.015, PMID 15734104

- United Nations Office on Drugs Crime (2009). Recommended methods for the identification and analysis of cannabis and cannabis products [electronic resource] : manual for use by national drug testing laboratories (PDF) (Rev. and updated. ed.). New York: United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-148242-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017.

- Hanna, Ab (2018-01-26). "What Is THCA Crystalline?". High Times. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- McPartland, JM; MacDonald, C; Young, M; Grant, PS; Furkert, DP; Glass, M (2017). "Affinity and Efficacy Studies of Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid A at Cannabinoid Receptor Types One and Two". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1089/can.2016.0032. PMC 5510775. PMID 28861508.

- Verhoeckx, Kitty C.M.; Korthout, Henrie A.A.J.; Van Meeteren-Kreikamp, A.P.; Ehlert, Karl A.; Wang, Mei; Van Der Greef, Jan; Rodenburg, Richard J.T.; Witkamp, Renger F. (2006-04-01). "Unheated Cannabis sativa extracts and its major compound THC-acid have potential immuno-modulating properties not mediated by CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways". International Immunopharmacology. 6 (4): 656–665. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2005.10.002. ISSN 1567-5769. PMID 16504929.

- Nallathambi, Rameshprabu; Mazuz, Moran; Ion, Aurel; Selvaraj, Gopinath; Weininger, Smadar; Fridlender, Marcelo; Nasser, Ahmad; Sagee, Oded; Kumari, Puja (2017-07-01). "Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Colon Models Is Derived from Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid That Interacts with Additional Compounds in Cannabis Extracts". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2 (1): 167–182. doi:10.1089/can.2017.0027. ISSN 2378-8763. PMC 5627671. PMID 29082314.

- Nadal, Xavier; del Río, Carmen; Casano, Salvatore; Palomares, Belén; Ferreiro‐Vera, Carlos; Navarrete, Carmen; Sánchez‐Carnerero, Carolina; Cantarero, Irene; Bellido, Maria Luz (2017). "Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid is a potent PPARγ agonist with neuroprotective activity". British Journal of Pharmacology. 174 (23): 4263–4276. doi:10.1111/bph.14019. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 5731255. PMID 28853159.

- Huestis, Marilyn A.; Mazzoni, Irene; Rabin, Olivier (2011-11-01). "Cannabis in Sport". Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 41 (11): 949–966. doi:10.2165/11591430-000000000-00000. ISSN 0112-1642. PMC 3717337. PMID 21985215.

- Jung, Julia; Kempf, Juergen; Mahler, Hellmut; Weinmann, Wolfgang (March 2007). "Detection of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A in human urine and blood serum by LC-MS/MS". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 42 (3): 354–360. Bibcode:2007JMSp...42..354J. doi:10.1002/jms.1167. ISSN 1076-5174. PMID 17219606.

- Brenneisen, Rudolf (2007). "Chapter 2: Chemistry and Analysis of Phytocannabinoids and Other Cannabis Constituents". In ElSohly, Mahmoud A. (ed.). Marijuana and the Cannabinoids. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press/Springer. pp. 17–49. ISBN 978-1-59259-947-9.

- Skell, J. M.; Kahn, M.; Foxman, B. M. (2021-02-01). "Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A, the precursor to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)". Acta Crystallographica Section C: Structural Chemistry. 77 (2): 84–89. doi:10.1107/S2053229621000280. ISSN 2053-2296.

- Rosenqvist, E.; Ottersen, T.; Hörnfeldt, A.-B.; Liaaen-Jensen, S.; Schroll, G.; Altona, C. (1975). "The Crystal and Molecular Structure of Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid B." Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 29b: 379–384. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.29b-0379. ISSN 0904-213X.

- Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971

- "§1308.11 Schedule I." Archived from the original on 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- Erowid Analog Law Vault : Federal Controlled Substance Analogue Act Summary