Transgender hormone therapy

Transgender hormone therapy, also called hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), is a form of hormone therapy in which sex hormones and other hormonal medications are administered to transgender or gender nonconforming individuals for the purpose of more closely aligning their secondary sexual characteristics with their gender identity. This form of hormone therapy is given as one of two types, based on whether the goal of treatment is masculinization or feminization:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy – for transgender men or transmasculine people; consists of androgens and antiestrogens.

- Feminizing hormone therapy – for transgender women or transfeminine people; consists of estrogens and antiandrogens.

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

Some intersex people may also undergo hormone therapy, either starting in childhood to confirm the sex they were assigned at birth, or later in order to align their sex with their gender identity. Non-binary people may also engage in hormone therapy in order to achieve a desired balance of sex hormones or to help align their bodies with their gender identities.[1]

Requirements

The formal requirements to begin gender-affirming hormone therapy vary widely depending on geographic location and specific institution. Gender affirming hormones can be prescribed by a wide range of medical providers including, but not limited to, primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and obstetrician-gynecologists.[2]

Historically, many health centers required a psychiatric evaluation and/or a letter from a therapist before beginning therapy. Many centers now use an informed consent model that does not require any routine formal psychiatric evaluation but instead focuses on reducing barriers to care by ensuring a person can understand the risks, benefits, alternatives, unknowns, limitations, and risks of no treatment.[3] Some LGBT health organizations (notably Chicago's Howard Brown Health Center[4] and Planned Parenthood[5]) advocate for this type of informed consent model.

The Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People (SOC) require that patients seeking gender-affirmation hormone therapy be evaluated for gender dysphoria by either a mental health professional or hormone provider who is qualified in the area of transgender care. The Standards also require that the patient give informed consent, in other words, that they consent to the treatment after being fully informed of the risks involved.[6] Before beginning gender-affirming hormone therapy, the patient must be evaluated for significant medical and mental health concerns. If present, these must be addressed and reasonably well-controlled.[6]

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care, 7th edition, note that both of these approaches to care are appropriate.[2]

Gender dysphoria

Many international guidelines and institutions require persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria as a pre-requisite to starting gender-affirmation therapy. Gender dysphoria refers to the psychological discomfort or distress that an individual can experience if their sex assigned at birth is incongruent with that person's gender identity.[6] Signs of gender dysphoria can include comorbid mental health stressors such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and social isolation.[7] It is important to note that not all gender nonconforming individuals experience gender dysphoria.[8]

Treatment options

Guidelines

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the Endocrine Society formulated guidelines that created a foundation for health care providers to care for transgender patients.[9] UCSF guidelines are also used.[10] There is no generally agreed-upon set of guidelines, however.

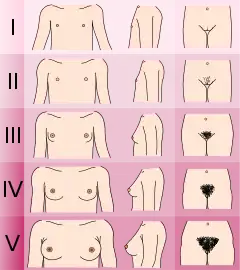

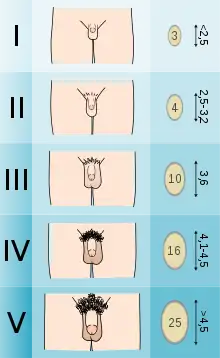

Delaying puberty in adolescents

Adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria may opt to undergo puberty-suppressing hormone therapy at the onset of puberty. The Standards of Care set forth by WPATH recommend individuals pursuing puberty-suppressing hormone therapy wait until at least experiencing Tanner Stage 2 pubertal development.[6] Tanner Stage 2 is defined by the appearance of scant pubic hair, breast bud development, and/or slight testicular growth.[11] WPATH classifies puberty-suppressing hormone therapy as a "fully reversible" intervention. Delaying puberty allows individuals more time to explore their gender identity before deciding on more permanent interventions and prevents the physical changes associated with puberty.[6]

The preferred puberty-suppressing agent for both individuals assigned male at birth and individuals assigned female at birth is a GnRH Analogue.[6] This approach temporarily shuts down the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis, which is responsible for the production of hormones (estrogen, testosterone) that cause the development of secondary sexual characteristics in puberty.[12]

Feminizing hormone therapy

Feminizing hormone therapy is typically used by transgender women, who desire the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. Individuals who identify as non-binary may also opt-in for feminizing hormone treatment to better align their body with their desired gender expression.[13] Feminizing hormone therapy usually includes medication to suppress testosterone production and induce feminization. Types of medications include estrogens, antiandrogens (testosterone blockers), and progestogens.[14] Most commonly, an estrogen is combined with an antiandrogen to suppress and block testosterone.[15] This allows for demasculinization and promotion of feminization and breast development. Estrogens are administered in various modalities including injection, transdermal patch, and oral tablets.[16]

The desired effects of feminizing hormone therapy focus on the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. These desired effects include: breast tissue development, redistribution of body fat, decreased body hair, reduction of muscle mass, and more.[15] The table below summarizes some of the effects of feminizing hormone therapy in transgender women:

| Effect | Time to expected onset of effect[lower-alpha 1] | Time to expected maximum effect[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] | Permanency if hormone therapy is stopped |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast development and nipple/areolar enlargement | 2–6 months | 1–5 years | Permanent |

| Thinning/slowed growth of facial/body hair | 4–12 months | >3 years[lower-alpha 3] | Reversible |

| Cessation/reversal of male-pattern scalp hair loss | 1–3 months | 1–2 years[lower-alpha 4] | Reversible |

| Softening of skin/decreased oiliness and acne | 3–6 months | Unknown | Reversible |

| Redistribution of body fat in a feminine pattern | 3–6 months | 2–5 years | Reversible |

| Decreased muscle mass/strength | 3–6 months | 1–2 years[lower-alpha 5] | Reversible |

| Widening and rounding of the pelvis[lower-alpha 6] | Unspecified | Unspecified | Permanent |

| Changes in mood, emotionality, and behavior | Unspecified | Unspecified | Reversible |

| Decreased sex drive | 1–3 months | 3–6 months | Reversible |

| Decreased spontaneous/morning erections | 1–3 months | 3–6 months | Reversible |

| Erectile dysfunction and decreased ejaculate volume | 1–3 months | Variable | Reversible |

| Decreased sperm production/fertility | Unknown | >3 years | Reversible or permanent[lower-alpha 7] |

| Decreased testicle size | 3–6 months | 2–3 years | Unknown |

| Decreased penis size | None[lower-alpha 8] | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Decreased prostate gland size | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Voice changes | None[lower-alpha 9] | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Footnotes and sources

Footnotes:

| |||

Masculinizing hormone therapy

Masculinizing hormone therapy is typically used by transgender men, who desire the development of masculine secondary sex characteristics. Masculinizing hormone therapy usually includes testosterone to produce masculinization and suppress the production of estrogen.[30] Treatment options include oral, parenteral, subcutaneous implant, and transdermal (patches, gels). Dosing is patient-specific and is discussed with the physician.[31] The most commonly prescribed methods are intramuscular and subcutaneous injections. This dosing can be weekly or biweekly depending on the individual patient.

Unlike feminizing hormone therapy, individuals undergoing masculinizing hormone therapy do not usually require additional hormone suppression such as estrogen suppression. Therapeutic doses of testosterone are usually sufficient to inhibit the production of estrogen to desired physiologic levels.[12]

The desired effects of masculinizing hormone therapy focus on the development of masculine secondary sex characteristics. These desired effects include: increased muscle mass, development of facial hair, voice deepening, increase and thickening of body hair, and more.[32]

| Reversible Changes | Irreversible Changes |

|---|---|

| Increased libido | Deepening of voice |

| Redistribution of body fat | Growth of facial/body hair |

| Cessation of ovulation/menstruation | Male-pattern baldness |

| Increased muscle mass | Enlargement of clitoris |

| Increased perspiration | Growth spurt/closure of growth plates |

| Acne | Breast atrophy |

| Increased RBC count |

Safety

Hormone therapy for transgender individuals has been shown in medical literature to be generally safe, when supervised by a qualified medical professional.[33] There are potential risks with hormone treatment that will be monitored through screenings and lab tests such as blood count (hemoglobin), kidney and liver function, blood sugar, potassium, and cholesterol.[31][14] Taking more medication than directed may lead to health problems such as increased risk of cancer, heart attack from thickening of the blood, blood clots, and elevated cholesterol.[31][34]

Feminizing hormone therapy

The Standards of Care published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) summarize many of the risks associated with feminizing hormone therapy (outlined below).[6] For more in-depth information on the safety profile of estrogen-based feminizing hormone therapy visit the feminizing hormone therapy page.

| Likely Increased Risk | Possible Increased Risk | Inconclusive/No Increased Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Venous Thromboembolic Disease | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Breast Cancer |

| Cardiovascular Events | Hypertension | |

| Increase Triglycerides | Increased Prolactin | |

| Transient Increase in Liver Enzymes | ||

| Gall Stones |

Masculinizing hormone therapy

The Standards of Care published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) summarize many of the risks associated with masculinizing hormone therapy (outlined below).[6] For more in-depth information on the safety profile of testosterone-based masculinizing hormone therapy visit the masculinizing hormone therapy page.

| Likely Increased Risk | Possible Increased Risk | Inconclusive/No Increased Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Polycythemia | Decreased HDL | Osteoporosis |

| Weight Gain | Transient Increase in Liver Enzymes | Cardiovascular Events |

| Hypertension | ||

| Breast, Cervical, Ovarian, Endometrial Cancer |

Fertility consideration

Transgender hormone therapy may limit fertility potential.[35] Should a transgender individual choose to undergo sex reassignment surgery, their fertility potential is lost completely.[36] Before starting any treatment, individuals may consider fertility issues and fertility preservation. Options include semen cryopreservation, oocyte cryopreservation, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation.[35][36]

A study due to be presented at ENDO 2019 (the Endocrine Society's conference) reportedly shows that even after one year of treatment with testosterone, a transgender man can preserve his fertility potential.[37]

Treatment eligibility

Many providers use informed consent, whereby someone seeking hormone therapy can sign a statement of informed consent and begin treatment without much gatekeeping. For other providers, eligibility is determined using major diagnostic tools such as ICD-10 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Psychiatric conditions can commonly accompany or present similar to gender incongruence and gender dysphoria. For this reason, patients are assessed using DSM-5 criteria or ICD-10 criteria in addition to screening for psychiatric disorders. The Endocrine Society requires physicians that diagnose gender dysphoria and gender incongruence to be trained in psychiatric disorders with competency in ICD-10 and DSM-5. The healthcare provider should also obtain a thorough assessment of the patient's mental health and identify potential psychosocial factors that can affect therapy.[38]

ICD-10

The ICD-10 system requires that patients have a diagnosis of either transsexualism or gender identity disorder of childhood. The criteria for transsexualism include:[39]

- A desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex, usually accompanied by a sense of discomfort with, or inappropriateness of, one's anatomic sex

- A wish to have surgery and hormonal treatment to make one's body as congruent as possible with one's preferred sex

Individuals cannot be diagnosed with transsexualism if their symptoms are believed to be a result of another mental disorder, or of a genetic or chromosomal abnormality.

For a child to be diagnosed with gender identity disorder of childhood under ICD-10 criteria, they must be pre-pubescent and have intense and persistent distress about being the opposite sex. The distress must be present for at least six months. The child must either:

- Have a preoccupation with stereotypical activities of the opposite sex – as shown by cross-dressing, simulating attire of the opposite sex, or an intense desire to join in the games and pastimes of the opposite sex – and reject stereotypical games and pastimes of the same sex, or

- Have persistent denial relating to their anatomy. This can be shown through a belief that they will grow up to be the opposite sex, that their genitals are disgusting or will disappear, or that it would be better not to have their genitals.

DSM

The DSM-5 states that at least two of the following criteria must be experienced for at least six months' duration for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria:[40]

- A strong desire to be of a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A strong desire to be treated as a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A significant incongruence between one's experienced or expressed gender and one's sexual characteristics

- A strong desire for the sexual characteristics of a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A strong desire to be rid of one's sexual characteristics due to incongruence with one's experienced or expressed gender

- A strong conviction that one has the typical reactions and feelings of a gender other than one's assigned gender

In addition, the condition must be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment.[40]

Readiness

Some organizations – but fewer than in the past – require that patients spend a certain period of time living in their desired gender role before starting hormone therapy. This period is sometimes called real-life experience (RLE). The Endocrine Society stated in 2009 that individuals should either have a documented three months of RLE or undergo psychotherapy for a period of time specified by their mental health provider, usually a minimum of three months.[41]

Transgender and gender non-conforming activists, such as Kate Bornstein, have asserted that RLE is psychologically harmful and is a form of "gatekeeping", effectively barring individuals from transitioning for as long as possible, if not permanently.[42]

Accessibility

Gender-affirming care is health care that affirms people to live authentically in their genders, no matter the gender they were assigned at birth or the path their gender affirmation (or transition) takes. It allows each person to seek only the changes or medical interventions they desire to affirm their own gender identity, and hormone therapy (“HRT” or gender-affirming hormone therapy) may be a part of that.[43]

Some transgender people choose to self-administer hormone replacement medications, often because doctors have too little experience in this area, or because no doctor is available. Others self-administer because their doctor will not prescribe hormones without a letter from a psychotherapist stating that the patient meets the diagnostic criteria and is making an informed decision to transition. Many therapists require at least three months of continuous psychotherapy and/or real-life experience before they will write such a letter. Because many individuals must pay for evaluation and care out-of-pocket, costs can be prohibitive.

Access to medication can be poor even where health care is provided free. In a patient survey conducted by the United Kingdom's National Health Service in 2008, 5% of respondents acknowledged resorting to self-medication, and 46% were dissatisfied with the amount of time it took to receive hormone therapy. The report concluded in part: "The NHS must provide a service that is easy to access so that vulnerable patients do not feel forced to turn to DIY remedies such as buying drugs online with all the risks that entails. Patients must be able to access professional help and advice so that they can make informed decisions about their care, whether they wish to take the NHS or private route without putting their health and indeed their lives in danger."[44] Self-administration of hormone replacement medications may have untoward health effects and risks.[45]

A number of private companies have attempted to increase accessibility for hormone replacement medications and help transgender people navigate the complexities of access to treatment.

See also

- Hormone therapy

- Sex reassignment surgery

- Real-life experience (transgender)

References

- Ferguson, Joshua M. (November 30, 2017). "What It Means to Transition When You're Non-Binary". Teen Vogue.

- Deutsch MB, Feldman JL. Updated recommendations from the world professional association for transgender health standards of care. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Jan 15;87(2):89-93.

- UCSF Transgender Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People; 2nd edition. Deutsch MB, ed. June 2016. Available at transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines.

- Schreiber, Leslie. "Howard Brown Health Center Establishes Transgender Hormone Protocol". www.howardbrown.org. Howard Brown. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- "What Health Care & Services Do Transgender People Require?". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- Coleman, Eli; et al. (August 2012). "Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7". International Journal of Transgenderism. 13 (4): 165–232. doi:10.1080/15532739.2011.700873. S2CID 39664779.

- "Gender dysphoria". nhs.uk. 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- Olson-Kennedy, J; Cohen-Kettenis, P. T.; Kreukels, B.P.C; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L; Garofalo, R; Meyer, W; Rosenthal, S.M. (April 2016). "Research Priorities for Gender Nonconforming/Transgender Youth: Gender Identity Development and Biopsychosocial Outcomes". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 23 (2): 172–179. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000236. ISSN 1752-296X. PMC 4807860. PMID 26825472.

- Unger, Cécile A. (December 2016). "Hormone therapy for transgender patients". Translational Andrology and Urology. 5 (6): 877–884. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04. ISSN 2223-4691. PMC 5182227. PMID 28078219.

- "Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People | Transgender Care". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- Emmanuel, Mickey; Bokor, Brooke R. (2021), "Tanner Stages", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262142, retrieved 2021-11-12

- Bangalore Krishna, Kanthi; Fuqua, John S.; Rogol, Alan D.; Klein, Karen O.; Popovic, Jadranka; Houk, Christopher P.; Charmandari, Evangelia; Lee, Peter A. (2019). "Use of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogs in Children: Update by an International Consortium". Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 91 (6): 357–372. doi:10.1159/000501336. ISSN 1663-2818. PMID 31319416. S2CID 197664792.

- "Hormone Use for Non-Binary People | GenderGP". GenderGP.com. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- "Information on Estrogen Hormone Therapy | Transgender Care". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- "Overview of feminizing hormone therapy | Gender Affirming Health Program". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- "Overview of feminizing hormone therapy | Gender Affirming Health Program". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW (September 2010). "Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life". J Sex Med. 7 (9): 2996–3010. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x. PMID 20626600.

- Higano CS (February 2003). "Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy: monitoring and minimizing toxicity". Urology. 61 (2 Suppl 1): 32–8. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02397-X. PMID 12667885.

- Higano CS (October 2012). "Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer". J. Clin. Oncol. 30 (30): 3720–5. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8509. PMID 23008326.

- Eberhard Nieschlag; Hermann Behre (29 June 2013). Andrology: Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-3-662-04491-9.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, Hannema SE, Meyer WJ, Murad MH, Rosenthal SM, Safer JD, Tangpricha V, T'Sjoen GG (November 2017). "Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline" (PDF). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102 (11): 3869–3903. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01658. PMID 28945902. S2CID 3726467.

- Coleman, E.; Bockting, W.; Botzer, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.; DeCuypere, G.; Feldman, J.; Fraser, L.; Green, J.; Knudson, G.; Meyer, W. J.; Monstrey, S.; Adler, R. K.; Brown, G. R.; Devor, A. H.; Ehrbar, R.; Ettner, R.; Eyler, E.; Garofalo, R.; Karasic, D. H.; Lev, A. I.; Mayer, G.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.; Hall, B. P.; Pfaefflin, F.; Rachlin, K.; Robinson, B.; Schechter, L. S.; Tangpricha, V.; van Trotsenburg, M.; Vitale, A.; Winter, S.; Whittle, S.; Wylie, K. R.; Zucker, K. (2012). "Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7" (PDF). International Journal of Transgenderism. 13 (4): 165–232. doi:10.1080/15532739.2011.700873. ISSN 1553-2739. S2CID 39664779.

- Bourns, Amy (2015). "Guidelines and Protocols for Comprehensive Primary Care for Trans Clients" (PDF). Sherbourne Health Centre. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Fabris B, Bernardi S, Trombetta C (March 2015). "Cross-sex hormone therapy for gender dysphoria". J. Endocrinol. Invest. 38 (3): 269–82. doi:10.1007/s40618-014-0186-2. hdl:11368/2831597. PMID 25403429. S2CID 207503049.

- Moore E, Wisniewski A, Dobs A (August 2003). "Endocrine treatment of transsexual people: a review of treatment regimens, outcomes, and adverse effects". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (8): 3467–73. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021967. PMID 12915619.

- Asscheman, Henk; Gooren, Louis J.G. (1993). "Hormone Treatment in Transsexuals". Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 5 (4): 39–54. doi:10.1300/J056v05n04_03. ISSN 0890-7064. S2CID 144580633.

- Levy A, Crown A, Reid R (October 2003). "Endocrine intervention for transsexuals". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 59 (4): 409–18. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01821.x. PMID 14510900. S2CID 24493388.

- de, Blok Christel; Klaver, Maartje; Nota, Nienke; Dekker, Marieke; den, Heijer Martin (2016). "Breast development in male-to-female transgender patients after one year cross-sex hormonal treatment". Endocrine Abstracts. doi:10.1530/endoabs.41.GP146. ISSN 1479-6848.

- de Blok CJ, Klaver M, Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, Heijboer AC, Fisher AD, Schreiner T, T'Sjoen G, den Heijer M (February 2018). "Breast Development in Transwomen After 1 Year of Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Study". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103 (2): 532–538. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01927. PMID 29165635. S2CID 3716975.

- "Masculinizing hormone therapy - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Information on Testosterone Hormone Therapy | Transgender Care". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- "Overview of masculinizing hormone therapy | Gender Affirming Health Program". transcare.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- Weinand, J. D.; Safer, J. D. (June 2015). "Weinand J, Safer J. Feb 2015. "Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision; A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals." Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology (2015)". Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology. 2 (2): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2015.02.003. PMC 5226129. PMID 28090436.

- Task Force on Oral Contraceptives; Koetsawang, Suporn; Mandlekar, A.V.; Krishna, Usha R.; Purandare, V.N.; Deshpande, C.K.; Chew, S.C.; Fong, Rosilind; Ratnam, S.S.; Kovacs, L.; Zalanyi, S. (May 1980). "A randomized, double-blind study of two combined oral contraceptives containing the same progestogen, but different estrogens". Contraception. 21 (5): 445–459. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(80)90010-4. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 7428356.

- TʼSjoen, Guy; Van Caenegem, Eva; Wierckx, Katrien (2013). "Transgenderism and reproduction". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 20 (6): 575–579. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000436184.42554.b7. ISSN 1752-2978. PMID 24468761. S2CID 205398449.

- De Sutter, P. (2001). "Gender reassignment and assisted reproduction: present and future reproductive options for transsexual people". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 16 (4): 612–614. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.4.612. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 11278204.

- "Ovary function is preserved in transgender men at one year of testosterone therapy | Endocrine Society". www.endocrine.org. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "CORRIGENDUM FOR "Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline"". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 103 (7): 2758–2759. 2018-07-01. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01268. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 29905821.

- "ICD-10 Diagnostic Codes". ICD-10:Version 2010. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- American Psychiatry Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Washington, DC and London: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 451–460. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- Hembree, Wylie, C; Cohen-Kettenis, Peggy; Delemarre-van de Waal, Henriette; Gooren, Louis; Meyer III, Walter; Spack, Norman; Tangpricha, Vin; Montori, Victor (September 2009). "Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 94 (9): 3132–54. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0345. PMID 19509099.

- Bornstein, Kate (2013). My Gender Workbook, Updated : How to Become a Real Man, a Real Woman, the Real You, or Something Else Entirely (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415538657.

- "Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy 101: Introducing the #HRTSavesLives Campaign". 10 August 2020.

- "Survey of Patient Satisfaction with Transgender Services" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Becerra Fernández A, de Luis Román DA, Piédrola Maroto G (October 1999). "Morbilidad en pacientes transexuales con autotratamiento hormonal para cambio de sexo" [Morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender hormone self-treatment] (PDF). Med Clin (Barc) (in Spanish). 113 (13): 484–7. ISSN 0025-7753. PMID 10604171. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-08. Retrieved 2018-11-11.