Unstable angina

| Unstable angina | |

|---|---|

| |

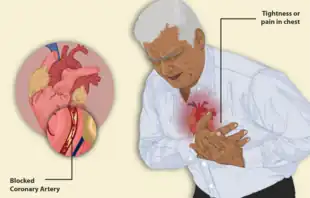

| Illustration depicting angina | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | chest pain or chest discomfort at rest, lasting for less than 30 minutes, or a new onset chest pain or discomfort on exertion. |

| Complications | The certainty of a heart attack or coronary artery disease |

Unstable angina (UA), also called crescendo angina, is a type of angina pectoris[1] that is irregular.[2] It is also classified as a type of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).[3]

It can be difficult to distinguish unstable angina from non-ST elevation (non-Q wave) myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).[4][5] They differ primarily in whether the ischemia is severe enough to cause sufficient damage to the heart's muscular cells to release detectable quantities of a marker of injury (typically troponin T or troponin I). Unstable angina is considered to be present in patients with ischemic symptoms suggestive of an ACS and no elevation in troponin, with or without ECG changes indicative of ischemia (e.g., ST segment depression or transient elevation or new T wave inversion). Since an elevation in troponin may not be detectable for up to 12 hours after presentation, UA and NSTEMI are frequently indistinguishable at initial evaluation.

Signs and symptoms

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of unstable angina is controversial. Until recently, unstable angina was assumed to be angina pectoris caused by disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque with partial thrombosis and possibly embolization or vasospasm leading to myocardial ischemia.[6][7] However, sensitive troponin assays reveal rise of cardiac troponin in the bloodstream with episodes of even mild myocardial ischemia. [8] Since unstable angina is assumed to occur in the setting of acute myocardial ischemia without troponin release, the concept of unstable angina is being questioned with some calling for retiring the term altogether.[9]

Diagnosis

Unstable angina is characterized by at least one of the following:

- Occurs at rest or minimal exertion and usually lasts more than 20 minutes (if nitroglycerin is not administered)

- Being severe (at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification 3) and of new onset (i.e. within 1 month)

- Occurs with a crescendo pattern (brought on by less activity, more severe, more prolonged or increased frequency than previously).[10][11]

Fifty percent of people with unstable angina will have evidence of necrosis of the heart's muscular cells based on elevated cardiac serum markers such as creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK)-MB and troponin T or I, and thus have a diagnosis of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction.[11][12]

Management

Nitroglycerin can be used immediately to dilate the venous system and reduce the circulating blood volume, therefore reducing the work and oxygen demand of the heart.[13][14] In addition, nitroglycerin causes peripheral venous and artery dilation reducing cardiac preload and afterload. These reductions allow for decreased stress on the heart and therefore lower the oxygen demand of the heart's muscle cells.[15]

Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and clopidogrel can reduce platelet aggregation at the unstable atherosclerotic plaque, as well as combining these with an anticoagulant such as a low molecular weight heparin, can reduce clot formation.

See also

References

- ↑ Yeghiazarians Y, Braunstein JB, Askari A, Stone PH (January 2000). "Unstable angina pectoris". N. Engl. J. Med. 342 (2): 101–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM200001133420207. PMID 10631280.

- ↑ "unstable angina" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Wiviott, S. D.; Braunwald, E (2004). "Unstable Angina and Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Part I. Initial Evaluation and Management, and Hospital Care". American Family Physician. 70 (3): 525–32. PMID 15317439.

- ↑ Roffi, M; et al. (2016). "2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". European Heart Journal. 37 (3): 267–315. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. PMID 26320110.

- ↑ Jneid, H; et al. (2012). "2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 60 (7): 645–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.004. PMID 22809746.

- ↑ Robbins (2005). Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.).

- ↑ Braunwald, E. (1998). "Unstable Angina: An Etiologic Approach to Management". Circulation. 98 (21): 2219–2222. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.98.21.2219. PMID 9826306.

- ↑ Sabatine, M. S.; Morrow, R. W.; de Lemos, J.A.; Jarolim, P.; Braunwald, E. (2009). "Detection of acute changes in circulating troponin in the setting of transient stress test-induced myocardial ischaemia using an ultrasensitive assay: results from TIMI 35". European Heart Journal. 30 (2): 162–169. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn504. PMC 2721709. PMID 18997177.

- ↑ Braunwald, E.; Morrow, R. W. (2013). "Unstable Angina. Is It Time for a Requiem?". Circulation. 127 (24): 2452–2457. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001258. PMID 23775194.

- ↑ Braunwald, E; et al. (2002). "ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction-2002: Summary Article: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina)". Circulation. 106 (14): 1893–1900. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000037106.76139.53. PMID 12356647.

- 1 2 Libby: Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine

- ↑ Markenvard, J; Dellborg, M; Jagenburg, R; Swedberg, K (1992). "The predictive value of CKMB mass concentration in unstable angina pectoris: preliminary report". Journal of Internal Medicine. 231 (4): 433–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00956.x. PMID 1588271.

- ↑ Murrell, William (1879). "Nitroglycerin as a remedy for angina pectoris". The Lancet. 1: 80–81, 113–115, 151–152, 225–227. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)46032-1. hdl:2027/uc1.b5295238.

- ↑ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8.

- ↑ Sidhu, M.; Boden, W. E.; Padala, S. K.; Cabral, K.; Buschmann, . (2015). "Role of short-acting nitroglycerin in the management of ischemic heart disease". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 9: 4793–805. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S79116. PMC 4548722. PMID 26316714.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)