Tricuspid valve stenosis

| Tricuspid valve stenosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Tricuspid stenosis | |

| Video explanation of tricuspid disease | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Tiredness, shortness of breath, leg swelling, liver problems[1] |

| Causes | Rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, carcinoid syndrome, lupus, complication of a pacemaker[1] |

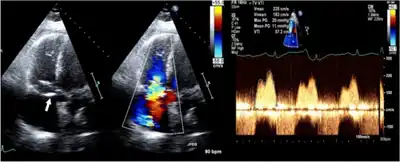

| Diagnostic method | Suspected based on a diastolic murmur, confirmed by ultrasound of the heart[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid regurgitation, atrial myxoma[1] |

| Treatment | Furosemide, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

Tricuspid valve stenosis is a type of valvular heart disease in which there is narrowing of the tricuspid valve opening.[1] Initial symptoms may include tiredness and shortness of breath with exercise.[1] More severe disease may result in leg swelling and liver problems.[1] It is often associated with mitral stenosis and aortic valve disease.[2]

It occurs most commonly due to rheumatic heart disease.[1] Other causes include infective endocarditis, carcinoid syndrome, lupus, and as a complication of a pacemaker.[1] Rare causes include Ebstein's anomaly and the medication fenfluramine.[1] Normally, the tricuspid valve opening is about 4 cm2.[1] A decrease in area below 1 cm2 is severe disease.[1] The diagnosis may be suspected based on a diastolic murmur and confirmed by ultrasound of the heart.[1]

Furosemide may be used to help with fluid overload.[1] In severe cases surgery, either in the form of a valvotomy, valve repair, of valve replacement, maybe done.[1] Outcomes depend on the underlying cause.[1]

Tricuspid stenosis is rare, making up about 2.4% of tricuspid valve disease.[1] Young women are most commonly affected.[1] The first tricuspid valve replacement was in 1966.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Initial symptoms may include tiredness and shortness of breath with exercise.[1] More severe disease may result in leg swelling and liver problems.[1] It is often associated with mitral stenosis.[1]

Cause

It occurs most commonly due to rheumatic heart disease and is often associated with mitral and aortic valve disease.[2] It can occur in carcinoid syndrome.[4] It may be induced by pacemaker leads.[5]

Diagnosis

A rumbling mid-diastolic murmur can be heard during auscultation caused by the blood flow through the stenotic valve.[2] It is best heard over the left sternal border.[2] A tricuspid opening snap may be heard,[2] with wide-splitting S2. It may increase in intensity with inspiration (Carvallo's sign).

Tests include chest X-ray and ECG.[2] Diagnosis is confirmed by an echocardiograph, which will also allow the physician to assess its severity.[2]

Treatment

Tricuspid valve stenosis itself usually doesn't require treatment. If stenosis is mild, monitoring the condition closely suffices. However, severe stenosis, or damage to other valves in the heart, may require surgical repair or replacement.

The treatment is usually by surgery (tricuspid valve replacement) or percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty. The resultant tricuspid regurgitation from percutaneous treatment is better tolerated than the insufficiency occurring during mitral valvuloplasty.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Golamari, R; Bhattacharya, PT (January 2020). "Tricuspid Stenosis". PMID 29763166.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bunce, Nicholas H.; Ray, Robin; Patel, Hitesh (2020). "30. Cardiology". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1110–1101. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ↑ Kapoor, Amar S.; Reynolds, Ralph D. (2012). Cancer and the Heart. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-4612-4898-9. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- ↑ Kilickapp, Saadettin; Yalcin, Suayib (2015). "29. Carcinoid syndrome". In Yalcin, Suayib; Öberg, Kjell (eds.). Neuroendocrine Tumours: Diagnosis and Management. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 515. ISBN 978-3-662-45214-1. Archived from the original on 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ↑ Ing, Frank; Sullivan, Patrick; Takao, Cheryl (2018). "Chapter 46 - Catheter Device Therapies for Heart Failure". Heart Failure in the Child and Young Adult. Academic Press. pp. 583–622. ISBN 978-0-12-802393-8. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |