Chiquitano language

Chiquitano (also Bésɨro or Tarapecosi) is an indigenous language isolate spoken in the central region of Santa Cruz Department of eastern Bolivia and the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil.

| Chiquitano | |

|---|---|

| Besïro | |

| Native to | Bolivia, Brazil |

| Region | Santa Cruz (Bolivia); Mato Grosso (Brazil) |

| Ethnicity | perhaps about 100,000 Chiquitano people |

Native speakers | 2,400 (2021)[1] |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | cax |

| Glottolog | chiq1253 Chiquitanosans1265 Sansimoniano |

| ELP | Chiquitano |

Classification

Chiquitano is usually considered to be a language isolate. Joseph Greenberg linked it to the Macro-Jê languages in his proposal,[2] but the results of his study have been later questioned due to methodological flaws.[3][4]

Kaufman (1994) suggests a relationship with the Bororoan languages.[5] Adelaar (2008) classifies Chiquitano as a Macro-Jê language,[6] while Nikulin (2020) suggests that Chiquitano is rather a sister of Macro-Jê.[7]

Varieties

Mason (1950)

- Chiquito

- North (Chiquito)

- Manasí (Manacica)

- Penoki (Penokikia)

- Pinyoca; Kusikia

- Tao; Tabiica

- Churapa

Loukotka (1968)

According to Čestmír Loukotka (1968), dialects were Tao (Yúnkarirsh), Piñoco, Penoqui, Kusikia, Manasi, San Simoniano, Churapa.[9]

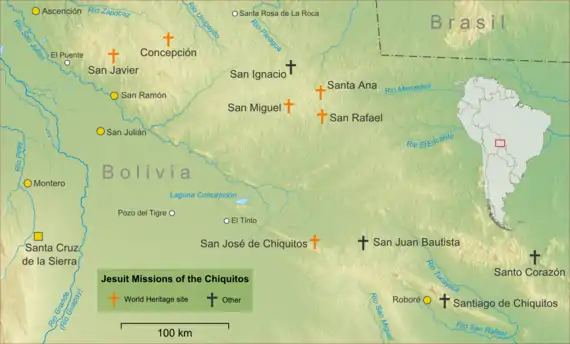

- Tao (Yúnkarirsh) - spoken at the old missions of San Rafael, Santa Ana, San Miguel, San Ignacio, San Juan, Santo Corazón, and Concepción, Bolivia.

- Piñoco - spoken at the missions of San Xavier, San José, and San José de Buenaventura.

- Penoqui - spoken at the old mission of San José. (However, Combès suggests that Penoqui was a synonym of Gorgotoqui and may have been a Bororoan language.[10][11])

- Cusiquia - once spoken north of the Penoqui tribe.

- Manasi - once spoken at the old missions of San Francisco Xavier and Concepción, Santa Cruz province.

- San Simoniano - now spoken in the Sierra de San Simón and the Danubio River.

- Churapa - spoken on the Piray River, Santa Cruz province.

Otuke, a Bororoan language, was also spoken in some of the missions.[9]

Nikulin (2020)

Chiquitano varieties listed by Nikulin (2020):[7]

- Chiquitano

- Bésɨro (also known as Lomeriano Chiquitano), spoken in the Lomerío region and in Concepción, Ñuflo de Chávez Province. Co-official status and has a standard orthography.

- Migueleño Chiquitano (in San Miguel de Velasco and surroundings), moribund with fewer than 30 speakers

- Eastern[1]

- Ignaciano Chiquitano (in San Ignacio de Velasco and surroundings)[12]

- Santiagueño Chiquitano (in Santiago de Chiquitos)

- Divergent varieties

- Sansimoniano (spoken in the far northeast of Beni Department)

- Piñoco (formerly spoken in the missions of San José de los Boros, San Francisco Xavier de los Piñoca, and San José de Buenavista/Desposorios; see also Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos)

Nikulin (2019) proposes that Camba Spanish has a Piñoco substratum. Camba Spanish was originally spoken in Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia, but is now also spoken in Beni Department and Pando Department.[13]

Some Chiquitano also prefer to call themselves Monkóka (plural form for 'people'; the singular form for 'person' is Monkóxɨ).[1]

Nikulin also tentatively proposes an Eastern subgroup for the varieties spoken in San Ignacio de Velasco, Santiago de Chiquitos, and Brazil.[1]

In Brazil, Chiquitano is spoken in the municipalities of Cáceres, Porto Esperidião, Pontes e Lacerda, and Vila Bela da Santíssima Trindade in the state of Mato Grosso.[14][15]

Historical subgroups

The following list of Jesuit and pre-Jesuit-era historical dialect groupings of Chiquitano is from Nikulin (2019),[13] after Matienzo et al. (2011: 427–435)[16] and Hervás y Panduro (1784: 30).[17] The main dialect groups were Tao, Piñoco, and Manasi.

| Subgroup | Location(s) |

|---|---|

| Aruporé, Bohococa (Bo(h)oca) | Concepción |

| Bacusone (Basucone, Bucofone, Bucojore) | San Rafael |

| Boro (Borillo) | San José, San Juan Bautista, Santo Corazón |

| Chamaru (Chamaro, Xamaru, Samaru, Zamanuca) | San Juan Bautista |

| Pequica | San Juan Bautista, afterwards San Miguel |

| Piococa | San Ignacio, Santa Ana |

| Piquica | east of the Manasicas |

| Purasi (Puntagica, Punasica, Punajica, Punaxica) | San Javier, Concepción |

| Subareca (Subarica, Subereca, Subercia, Xubereca) | San Javier |

| Tabiica (Tabica, Taviquia) | San Rafael, San Javier |

| Tau (Tao, Caoto) | San Javier, San José, San Miguel, San Rafael, San Juan Bautista, Santo Corazón |

| Tubasi (Tubacica, Tobasicoci) | San Javier, afterwards Concepción |

| Quibichoca (Quibicocha, Quiviquica, Quibiquia, Quibichicoci), Tañepica, Bazoroca | unknown |

| Subgroup | Location(s) |

|---|---|

| Guapa, Piñoca, Piococa | San Javier |

| Motaquica, Poxisoca, Quimeca, Quitaxica, Zemuquica, Taumoca | ? San Javier, San José, San José de Buenavista or Desposorios (Moxos) |

| Subgroup | Location(s) |

|---|---|

| Manasica, Yuracareca, Zibaca (Sibaca) | Concepción |

| Moposica, Souca | east of the Manasicas |

| Sepe (Sepeseca), Sisooca, (?) Sosiaca | north of the Manasicas |

| Sounaaca | west of the Manasicas |

| Obariquica, Obisisioca, Obobisooca, Obobococa, Osaaca, Osonimaca, Otaroso, Otenenema, Otigoma | northern Chiquitanía |

| Ochisirisa, Omemoquisoo, Omeñosisopa, Otezoo, Oyuri(ca) | northeastern Chiquitanía |

| Cuzica (Cusica, Cusicoci), Omonomaaca, Pichasica, Quimomeca, Totaica (Totaicoçi), Tunumaaca, Zaruraca | unknown |

Penoquí (Gorgotoqui?), possibly a Bororoan language, was spoken in San José.

Phonology

Syllable structure

The language has CV, CVV, and CVC syllables. It does not allow complex onsets or codas. The only codas allowed are nasal consonants.

Vocabulary

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for different dialects of Chiquito (Chiquitano).[20]

gloss Chiquito Yúnkarirsh San Simoniano Churápa tooth oh-ox oän noosh tongue otús natä iyúto foot popez popess pipín ípiop woman pais páirsh paá páish water toʔus tush túʔush fire péz péesh peés sun suur suursh sóu súush manioc tauax táhuash tabá tawásh tapir okitapakis tapakish oshtápakish house ogox póosh ípiosh red kiturixi kéturuk kéturikí

For a vocabulary list of Chiquitano by Santana (2012),[21] see the Portuguese Wiktionary.

Language contact

Chiquitano has borrowed extensively from an unidentified Tupí-Guaraní variety; one example is Chiquitano takones [takoˈnɛs] ‘sugarcane’, borrowed from a form close to Paraguayan Guaraní takuare'ẽ ‘sugarcane’.[13]: 8 There are also numerous Spanish borrowings.

Chiquitano (or an extinct variety close to it) has influenced the Camba variety of Spanish. This is evidenced by the numerous lexical borrowings of Chiquitano origin in local Spanish. Examples include bi ‘genipa’, masi ‘squirrel’, peni ‘lizard’, peta ‘turtle, tortoise’, jachi ‘chicha leftover’, jichi ‘worm; jichi spirit’, among many others.[13]

Further reading

- Galeote Tormo, J. (1993). Manitana Auqui Besüro: Gramática Moderna de la lengua Chiquitana y Vocabulario Básico. Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Los Huérfanos.

- Santana, A. C. (2005). Transnacionalidade lingüística: a língua Chiquitano no Brasil. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás. (Masters dissertation).

- Nikulin, Andrey. 2019. ¡Manityaka au r-ózura! Diccionario básico del chiquitano migueleño: El habla de San Miguel de Velasco y de San Juan de Lomerío.

References

- Nikulin, Andrey (May 26, 2021). "Chiquitano: a presentation". Universität Bonn.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1987). Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Rankin, Robert. (1992). [Review of Language in the Americas by J. H. Greenberg]. International Journal of American Linguistics, 58 (3), 324-351.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1988). [Review of Language in the Americas, Greenberg 1987]. Language, 64, 591-615.

- Kaufman, Terrence. 1994. The native languages of South America. In: Christopher Moseley and R. E. Asher (eds.), Atlas of the World’s Languages, 59–93. London: Routledge.

- Adelaar, Willem F. H. Relações externas do Macro-Jê: O caso do Chiquitano. In: Telles de A. P. Lima, Stella Virgínia; Aldir S. de Paula (eds.). Topicalizando Macro-Jê. Recife: Nectar, 2008. p. 9–27.

- Nikulin, Andrey. 2020. Proto-Macro-Jê: um estudo reconstrutivo. Doctoral dissertation, University of Brasília.

- Mason, John Alden (1950). "The languages of South America". In Steward, Julian (ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 6. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 143. pp. 157–317.

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian Languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center. pp. 60.

- Combès, Isabelle. 2010. Diccionario étnico: Santa Cruz la Vieja y su entorno en el siglo XVI. Cochabamba: Itinera-rios/Instituto Latinoamericano de Misionología. (Colección Scripta Autochtona, 4.)

- Combès, Isabelle. 2012. Susnik y los gorgotoquis. Efervescencia étnica en la Chiquitania (Oriente boliviano), p. 201–220. Indiana, v. 29. Berlín. doi:10.18441/ind.v29i0.201-220

- CIUCCI, L.; MACOÑÓ TOMICHÁ, J. 2018. Diccionario básico del chiquitano del Municipio de San Ignacio de Velasco. Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Ind. Maderera “San Luis” S. R. L., Museo de Historia. U. A. R. G. M. 61 f.

- Nikulin, Andrey (2020). "Contacto de lenguas en la Chiquitanía". Revista Brasileira de Línguas Indígenas. 2 (2): 5–30. doi:10.18468/rbli.2019v2n2.p05-30. S2CID 225674786.

- Santana, Áurea Cavalcante. 2012. Línguas cruzadas, histórias que se mesclam: ações de documentação, valorização e fortalecimento da língua Chiquitano no Brasil. Doutorado, Universidade Federal de Goiás.

- FUNAI/DAF. Plano de Desenvolvimento de Povos Indígenas (PDPI) – Grupo Indígena Chiquitano, MT. Diretoria de Assuntos Fundiários: Brasília, 2002.

- MATIENZO, J.; TOMICHÁ, R.; COMBÈS, I.; PAGE, C. Chiquitos en las Anuas de la Compañía de Jesús (1691–1767). Cochabamba: Itinerarios, 2011.

- HERVÁS Y PANDURO, L. Idea dell’Universo che contiene la storia della vita dell’uomo, elementi cos-mografici, viaggio estatico al mondo planetario, e storia della terra, e delle lingue. Vol. XVII: Ca-talogo delle lingue conosciute. Cesena: Gregorio Biasini, 1784.

- Krusi, Dorothee, Martin (1978). Phonology of Chiquitano.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sans, Pierric (2011), Proceedings of the VII Encontro Macro-Jê.Brasilia, Brazil

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- Santana, Áurea Cavalcante. 2012. Línguas cruzadas, histórias que se mesclam: ações de documentação, valorização e fortalecimento da língua Chiquitano no Brasil. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás.

- Fabre, Alain (2008-07-21). "Chiquitano" (PDF). Diccionario etnolingüístico y guía bibliográfica de los pueblos indígenas sudamericanos. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

External links

- Lenguas de Bolivia (online edition)