Xenon

Xenon is a chemical element with the symbol Xe and atomic number 54. It is a dense, colorless, odorless noble gas found in Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts.[13] Although generally unreactive, it can undergo a few chemical reactions such as the formation of xenon hexafluoroplatinate, the first noble gas compound to be synthesized.[14][15][16]

A xenon-filled discharge tube glowing light blue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xenon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | colorless gas, exhibiting a blue glow when placed in an electric field | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Xe) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xenon in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 54 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 18 (noble gases) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d10 5s2 5p6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 161.40 K (−111.75 °C, −169.15 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 165.051 K (−108.099 °C, −162.578 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 5.894 g/L | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 2.942 g/cm3[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 161.405 K, 81.77 kPa[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 289.733 K, 5.842 MPa[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.27 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 12.64 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 21.01[6] J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0, +2, +4, +6, +8 (rarely more than 0; a weakly acidic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.60 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 140±9 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 216 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

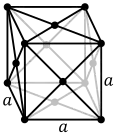

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | gas: 178 m·s−1 liquid: 1090 m/s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 5.65×10−3 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −43.9×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-63-3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | William Ramsay and Morris Travers (1898) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of xenon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xenon is used in flash lamps[17] and arc lamps,[18] and as a general anesthetic.[19] The first excimer laser design used a xenon dimer molecule (Xe2) as the lasing medium,[20] and the earliest laser designs used xenon flash lamps as pumps.[21] Xenon is also used to search for hypothetical weakly interacting massive particles[22] and as a propellant for ion thrusters in spacecraft.[23]

Naturally occurring xenon consists of seven stable isotopes and two long-lived radioactive isotopes. More than 40 unstable xenon isotopes undergo radioactive decay, and the isotope ratios of xenon are an important tool for studying the early history of the Solar System.[24] Radioactive xenon-135 is produced by beta decay from iodine-135 (a product of nuclear fission), and is the most significant (and unwanted) neutron absorber in nuclear reactors.[25]

History

Xenon was discovered in England by the Scottish chemist William Ramsay and English chemist Morris Travers in September 1898,[26] shortly after their discovery of the elements krypton and neon. They found xenon in the residue left over from evaporating components of liquid air.[27][28] Ramsay suggested the name xenon for this gas from the Greek word ξένον xénon, neuter singular form of ξένος xénos, meaning 'foreign(er)', 'strange(r)', or 'guest'.[29][30] In 1902, Ramsay estimated the proportion of xenon in the Earth's atmosphere to be one part in 20 million.[31]

During the 1930s, American engineer Harold Edgerton began exploring strobe light technology for high speed photography. This led him to the invention of the xenon flash lamp in which light is generated by passing brief electric current through a tube filled with xenon gas. In 1934, Edgerton was able to generate flashes as brief as one microsecond with this method.[17][32][33]

In 1939, American physician Albert R. Behnke Jr. began exploring the causes of "drunkenness" in deep-sea divers. He tested the effects of varying the breathing mixtures on his subjects, and discovered that this caused the divers to perceive a change in depth. From his results, he deduced that xenon gas could serve as an anesthetic. Although Russian toxicologist Nikolay V. Lazarev apparently studied xenon anesthesia in 1941, the first published report confirming xenon anesthesia was in 1946 by American medical researcher John H. Lawrence, who experimented on mice. Xenon was first used as a surgical anesthetic in 1951 by American anesthesiologist Stuart C. Cullen, who successfully used it with two patients.[34]

Xenon and the other noble gases were for a long time considered to be completely chemically inert and not able to form compounds. However, while teaching at the University of British Columbia, Neil Bartlett discovered that the gas platinum hexafluoride (PtF6) was a powerful oxidizing agent that could oxidize oxygen gas (O2) to form dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate (O+

2[PtF

6]−

).[35] Since O2 (1165 kJ/mol) and xenon (1170 kJ/mol) have almost the same first ionization potential, Bartlett realized that platinum hexafluoride might also be able to oxidize xenon. On March 23, 1962, he mixed the two gases and produced the first known compound of a noble gas, xenon hexafluoroplatinate.[36][16]

Bartlett thought its composition to be Xe+[PtF6]−, but later work revealed that it was probably a mixture of various xenon-containing salts.[37][38][39] Since then, many other xenon compounds have been discovered,[40] in addition to some compounds of the noble gases argon, krypton, and radon, including argon fluorohydride (HArF),[41] krypton difluoride (KrF2),[42][43] and radon fluoride.[44] By 1971, more than 80 xenon compounds were known.[45][46]

In November 1989, IBM scientists demonstrated a technology capable of manipulating individual atoms. The program, called IBM in atoms, used a scanning tunneling microscope to arrange 35 individual xenon atoms on a substrate of chilled crystal of nickel to spell out the three letter company initialism. It was the first time atoms had been precisely positioned on a flat surface.[47]

Characteristics

Xenon has atomic number 54; that is, its nucleus contains 54 protons. At standard temperature and pressure, pure xenon gas has a density of 5.894 kg/m3, about 4.5 times the density of the Earth's atmosphere at sea level, 1.217 kg/m3.[48] As a liquid, xenon has a density of up to 3.100 g/mL, with the density maximum occurring at the triple point.[49] Liquid xenon has a high polarizability due to its large atomic volume, and thus is an excellent solvent. It can dissolve hydrocarbons, biological molecules, and even water.[50] Under the same conditions, the density of solid xenon, 3.640 g/cm3, is greater than the average density of granite, 2.75 g/cm3.[49] Under gigapascals of pressure, xenon forms a metallic phase.[51]

Solid xenon changes from face-centered cubic (fcc) to hexagonal close packed (hcp) crystal phase under pressure and begins to turn metallic at about 140 GPa, with no noticeable volume change in the hcp phase. It is completely metallic at 155 GPa. When metallized, xenon appears sky blue because it absorbs red light and transmits other visible frequencies. Such behavior is unusual for a metal and is explained by the relatively small width of the electron bands in that state.[52][53]

(animated version)

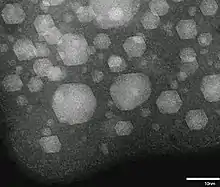

Liquid or solid xenon nanoparticles can be formed at room temperature by implanting Xe+ ions into a solid matrix. Many solids have lattice constants smaller than solid Xe. This results in compression of the implanted Xe to pressures that may be sufficient for its liquefaction or solidification.[54]

Xenon is a member of the zero-valence elements that are called noble or inert gases. It is inert to most common chemical reactions (such as combustion, for example) because the outer valence shell contains eight electrons. This produces a stable, minimum energy configuration in which the outer electrons are tightly bound.[55]

In a gas-filled tube, xenon emits a blue or lavenderish glow when excited by electrical discharge. Xenon emits a band of emission lines that span the visual spectrum,[56] but the most intense lines occur in the region of blue light, producing the coloration.[57]

Occurrence and production

Xenon is a trace gas in Earth's atmosphere, occurring at a volume fraction of 87±1 nL/L (parts per billion), or approximately 1 part per 11.5 million.[58] It is also found as a component of gases emitted from some mineral springs. Given a total mass of the atmosphere of 5.15×1018 kilograms (1.135×1019 lb), the atmosphere contains on the order of 2.03 gigatonnes (2.00×109 long tons; 2.24×109 short tons) of xenon in total when taking the average molar mass of the atmosphere as 28.96 g/mol which is equivalent to some 394 mass ppb.

Commercial

Xenon is obtained commercially as a by-product of the separation of air into oxygen and nitrogen.[59] After this separation, generally performed by fractional distillation in a double-column plant, the liquid oxygen produced will contain small quantities of krypton and xenon. By additional fractional distillation, the liquid oxygen may be enriched to contain 0.1–0.2% of a krypton/xenon mixture, which is extracted either by adsorption onto silica gel or by distillation. Finally, the krypton/xenon mixture may be separated into krypton and xenon by further distillation.[60][61]

Worldwide production of xenon in 1998 was estimated at 5,000–7,000 cubic metres (180,000–250,000 cu ft).[62] At a density of 5.894 grams per litre (0.0002129 lb/cu in) this is equivalent to roughly 30 to 40 tonnes (30 to 39 long tons; 33 to 44 short tons). Because of its scarcity, xenon is much more expensive than the lighter noble gases—approximate prices for the purchase of small quantities in Europe in 1999 were 10 €/L (=~€1.7/g) for xenon, 1 €/L (=~€0.27/g) for krypton, and 0.20 €/L (=~€0.22/g) for neon,[62] while the much more plentiful argon, which makes up over 1% by volume of earth's atmosphere, costs less than a cent per liter.

Solar System

Within the Solar System, the nucleon fraction of xenon is 1.56×10−8, for an abundance of approximately one part in 630 thousand of the total mass.[63] Xenon is relatively rare in the Sun's atmosphere, on Earth, and in asteroids and comets. The abundance of xenon in the atmosphere of planet Jupiter is unusually high, about 2.6 times that of the Sun.[64][lower-alpha 1] This abundance remains unexplained, but may have been caused by an early and rapid buildup of planetesimals—small, subplanetary bodies—before the heating of the presolar disk.[65] — otherwise, xenon would not have been trapped in the planetesimal ices. The problem of the low terrestrial xenon may be explained by covalent bonding of xenon to oxygen within quartz, reducing the outgassing of xenon into the atmosphere.[66]

Stellar

Unlike the lower-mass noble gases, the normal stellar nucleosynthesis process inside a star does not form xenon. Elements more massive than iron-56 consume energy through fusion, and the synthesis of xenon represents no energy gain for a star.[67] Instead, xenon is formed during supernova explosions during the r-process,[68] by the slow neutron-capture process (s-process) in red giant stars that have exhausted their core hydrogen and entered the asymptotic giant branch,[69] and from radioactive decay, for example by beta decay of extinct iodine-129 and spontaneous fission of thorium, uranium, and plutonium.[70]

Nuclear fission

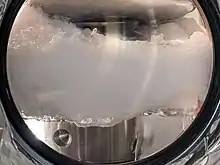

Xenon-135 is a notable neutron poison with a high fission product yield. As it is relatively short lived, it decays at the same rate it is produced during steady operation of a nuclear reactor. However, if power is reduced or the reactor is scramed, less xenon is destroyed than is produced from the beta decay of its parent nuclides. This phenomenon called xenon poisoning can cause significant problems in restarting a reactor after a scram or increasing power after it had been reduced and it was one of several contributing factors in the Chernobyl nuclear accident.[71][72]

Stable or extremely long lived isotopes of xenon are also produced in appreciable quantities in nuclear fission. Xenon-136 is produced when xenon-135 undergoes neutron capture before it can decay. The ratio of xenon-136 to xenon-135 (or its decay products) can give hints as to the power history of a given reactor and the absence of xenon-136 is a "fingerprint" for nuclear explosions, as xenon-135 is not produced directly but as a product of successive beta decays and thus it can't absorb any neutrons in a nuclear explosion which occurs in fractions of a second.[73]

The stable isotope xenon-132 has a fission product yield of over 4% in the thermal neutron fission of 235

U which means that stable or nearly stable xenon isotopes have a higher mass fraction in spent nuclear fuel (which is about 3% fission products) than it does in air. However, there is as of 2022 no commercial effort to extract xenon from spent fuel during nuclear reprocessing.[74][75]

Isotopes

Naturally occurring xenon is composed of seven stable isotopes: 126Xe, 128–132Xe, and 134Xe. The isotopes 126Xe and 134Xe are predicted by theory to undergo double beta decay, but this has never been observed so they are considered stable.[76] In addition, more than 40 unstable isotopes have been studied. The longest lived of these isotopes are the primordial 124Xe, which undergoes double electron capture with a half-life of 1.8×1022 yr,[77] and 136Xe, which undergoes double beta decay with a half-life of 2.11 × 1021 yr.[78] 129Xe is produced by beta decay of 129I, which has a half-life of 16 million years. 131mXe, 133Xe, 133mXe, and 135Xe are some of the fission products of 235U and 239Pu,[70] and are used to detect and monitor nuclear explosions.

Nuclear spin

Nuclei of two of the stable isotopes of xenon, 129Xe and 131Xe, have non-zero intrinsic angular momenta (nuclear spins, suitable for nuclear magnetic resonance). The nuclear spins can be aligned beyond ordinary polarization levels by means of circularly polarized light and rubidium vapor.[79] The resulting spin polarization of xenon nuclei can surpass 50% of its maximum possible value, greatly exceeding the thermal equilibrium value dictated by paramagnetic statistics (typically 0.001% of the maximum value at room temperature, even in the strongest magnets). Such non-equilibrium alignment of spins is a temporary condition, and is called hyperpolarization. The process of hyperpolarizing the xenon is called optical pumping (although the process is different from pumping a laser).[80]

Because a 129Xe nucleus has a spin of 1/2, and therefore a zero electric quadrupole moment, the 129Xe nucleus does not experience any quadrupolar interactions during collisions with other atoms, and the hyperpolarization persists for long periods even after the engendering light and vapor have been removed. Spin polarization of 129Xe can persist from several seconds for xenon atoms dissolved in blood[81] to several hours in the gas phase[82] and several days in deeply frozen solid xenon.[83] In contrast, 131Xe has a nuclear spin value of 3⁄2 and a nonzero quadrupole moment, and has t1 relaxation times in the millisecond and second ranges.[84]

From fission

Some radioactive isotopes of xenon (for example, 133Xe and 135Xe) are produced by neutron irradiation of fissionable material within nuclear reactors.[14] 135Xe is of considerable significance in the operation of nuclear fission reactors. 135Xe has a huge cross section for thermal neutrons, 2.6×106 barns,[25] and operates as a neutron absorber or "poison" that can slow or stop the chain reaction after a period of operation. This was discovered in the earliest nuclear reactors built by the American Manhattan Project for plutonium production. However, the designers had made provisions in the design to increase the reactor's reactivity (the number of neutrons per fission that go on to fission other atoms of nuclear fuel).[85] 135Xe reactor poisoning was a major factor in the Chernobyl disaster.[86] A shutdown or decrease of power of a reactor can result in buildup of 135Xe, with reactor operation going into a condition known as the iodine pit. Under adverse conditions, relatively high concentrations of radioactive xenon isotopes may emanate from cracked fuel rods,[87] or fissioning of uranium in cooling water.[88]

Isotope ratios of xenon produced in natural nuclear fission reactors at Oklo in Gabon reveal the reactor properties during chain reaction that took place about 2 billion years ago.[89]

Cosmic processes

Because xenon is a tracer for two parent isotopes, xenon isotope ratios in meteorites are a powerful tool for studying the formation of the Solar System. The iodine–xenon method of dating gives the time elapsed between nucleosynthesis and the condensation of a solid object from the solar nebula. In 1960, physicist John H. Reynolds discovered that certain meteorites contained an isotopic anomaly in the form of an overabundance of xenon-129. He inferred that this was a decay product of radioactive iodine-129. This isotope is produced slowly by cosmic ray spallation and nuclear fission, but is produced in quantity only in supernova explosions.[90][91]

Because the half-life of 129I is comparatively short on a cosmological time scale (16 million years), this demonstrated that only a short time had passed between the supernova and the time the meteorites had solidified and trapped the 129I. These two events (supernova and solidification of gas cloud) were inferred to have happened during the early history of the Solar System, because the 129I isotope was likely generated shortly before the Solar System was formed, seeding the solar gas cloud with isotopes from a second source. This supernova source may also have caused collapse of the solar gas cloud.[90][91]

In a similar way, xenon isotopic ratios such as 129Xe/130Xe and 136Xe/130Xe are a powerful tool for understanding planetary differentiation and early outgassing.[24] For example, the atmosphere of Mars shows a xenon abundance similar to that of Earth (0.08 parts per million[92]) but Mars shows a greater abundance of 129Xe than the Earth or the Sun. Since this isotope is generated by radioactive decay, the result may indicate that Mars lost most of its primordial atmosphere, possibly within the first 100 million years after the planet was formed.[93][94] In another example, excess 129Xe found in carbon dioxide well gases from New Mexico is believed to be from the decay of mantle-derived gases from soon after Earth's formation.[70][95]

Compounds

After Neil Bartlett's discovery in 1962 that xenon can form chemical compounds, a large number of xenon compounds have been discovered and described. Almost all known xenon compounds contain the electronegative atoms fluorine or oxygen. The chemistry of xenon in each oxidation state is analogous to that of the neighboring element iodine in the immediately lower oxidation state.[96]

Halides

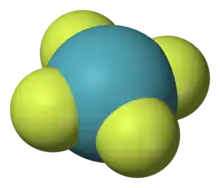

Three fluorides are known: XeF

2, XeF

4, and XeF

6. XeF is theorized to be unstable.[97] These are the starting points for the synthesis of almost all xenon compounds.

The solid, crystalline difluoride XeF

2 is formed when a mixture of fluorine and xenon gases is exposed to ultraviolet light.[98] The ultraviolet component of ordinary daylight is sufficient.[99] Long-term heating of XeF

2 at high temperatures under an NiF

2 catalyst yields XeF

6.[100] Pyrolysis of XeF

6 in the presence of NaF yields high-purity XeF

4.[101]

The xenon fluorides behave as both fluoride acceptors and fluoride donors, forming salts that contain such cations as XeF+

and Xe

2F+

3, and anions such as XeF−

5, XeF−

7, and XeF2−

8. The green, paramagnetic Xe+

2 is formed by the reduction of XeF

2 by xenon gas.[96]

XeF

2 also forms coordination complexes with transition metal ions. More than 30 such complexes have been synthesized and characterized.[100]

Whereas the xenon fluorides are well characterized, the other halides are not. Xenon dichloride, formed by the high-frequency irradiation of a mixture of xenon, fluorine, and silicon or carbon tetrachloride,[102] is reported to be an endothermic, colorless, crystalline compound that decomposes into the elements at 80 °C. However, XeCl

2 may be merely a van der Waals molecule of weakly bound Xe atoms and Cl

2 molecules and not a real compound.[103] Theoretical calculations indicate that the linear molecule XeCl

2 is less stable than the van der Waals complex.[104] Xenon tetrachloride and xenon dibromide are more unstable that they cannot be synthesized by chemical reactions. They were created by radioactive decay of 129

ICl−

4 and 129

IBr−

2, respectively.[105][106]

Oxides and oxohalides

Three oxides of xenon are known: xenon trioxide (XeO

3) and xenon tetroxide (XeO

4), both of which are dangerously explosive and powerful oxidizing agents, and xenon dioxide (XeO2), which was reported in 2011 with a coordination number of four.[107] XeO2 forms when xenon tetrafluoride is poured over ice. Its crystal structure may allow it to replace silicon in silicate minerals.[108] The XeOO+ cation has been identified by infrared spectroscopy in solid argon.[109]

Xenon does not react with oxygen directly; the trioxide is formed by the hydrolysis of XeF

6:[110]

- XeF

6 + 3 H

2O → XeO

3 + 6 HF

XeO

3 is weakly acidic, dissolving in alkali to form unstable xenate salts containing the HXeO−

4 anion. These unstable salts easily disproportionate into xenon gas and perxenate salts, containing the XeO4−

6 anion.[111]

Barium perxenate, when treated with concentrated sulfuric acid, yields gaseous xenon tetroxide:[102]

- Ba

2XeO

6 + 2 H

2SO

4 → 2 BaSO

4 + 2 H

2O + XeO

4

To prevent decomposition, the xenon tetroxide thus formed is quickly cooled into a pale-yellow solid. It explodes above −35.9 °C into xenon and oxygen gas, but is otherwise stable.

A number of xenon oxyfluorides are known, including XeOF

2, XeOF

4, XeO

2F

2, and XeO

3F

2. XeOF

2 is formed by reacting OF

2 with xenon gas at low temperatures. It may also be obtained by partial hydrolysis of XeF

4. It disproportionates at −20 °C into XeF

2 and XeO

2F

2.[112] XeOF

4 is formed by the partial hydrolysis of XeF

6,[113] or the reaction of XeF

6 with sodium perxenate, Na

4XeO

6. The latter reaction also produces a small amount of XeO

3F

2.

- XeF

6 + H

2O → XeOF

4 + 2 HF

XeO

2F

2 is also formed by partial hydrolysis of XeF

6.[114]

- XeF

6 + 2 H

2O → XeO

2F

2 + 4 HF

XeOF

4 reacts with CsF to form the XeOF−

5 anion,[112][115] while XeOF3 reacts with the alkali metal fluorides KF, RbF and CsF to form the XeOF−

4 anion.[116]

Other compounds

Xenon can be directly bonded to a less electronegative element than fluorine or oxygen, particularly carbon.[117] Electron-withdrawing groups, such as groups with fluorine substitution, are necessary to stabilize these compounds.[111] Numerous such compounds have been characterized, including:[112][118]

- C

6F

5–Xe+

–N≡C–CH

3, where C6F5 is the pentafluorophenyl group. - [C

6F

5]

2Xe - C

6F

5–Xe–C≡N - C

6F

5–Xe–F - C

6F

5–Xe–Cl - C

2F

5–C≡C–Xe+ - [CH

3]

3C–C≡C–Xe+ - C

6F

5–XeF+

2 - (C

6F

5Xe)

2Cl+

Other compounds containing xenon bonded to a less electronegative element include F–Xe–N(SO

2F)

2 and F–Xe–BF

2. The latter is synthesized from dioxygenyl tetrafluoroborate, O

2BF

4, at −100 °C.[112][119]

An unusual ion containing xenon is the tetraxenonogold(II) cation, AuXe2+

4, which contains Xe–Au bonds.[120] This ion occurs in the compound AuXe

4(Sb

2F

11)

2, and is remarkable in having direct chemical bonds between two notoriously unreactive atoms, xenon and gold, with xenon acting as a transition metal ligand.

The compound Xe

2Sb

2F

11 contains a Xe–Xe bond, the longest element-element bond known (308.71 pm = 3.0871 Å).[121]

In 1995, M. Räsänen and co-workers, scientists at the University of Helsinki in Finland, announced the preparation of xenon dihydride (HXeH), and later xenon hydride-hydroxide (HXeOH), hydroxenoacetylene (HXeCCH), and other Xe-containing molecules.[122] In 2008, Khriachtchev et al. reported the preparation of HXeOXeH by the photolysis of water within a cryogenic xenon matrix.[123] Deuterated molecules, HXeOD and DXeOH, have also been produced.[124]

Clathrates and excimers

In addition to compounds where xenon forms a chemical bond, xenon can form clathrates—substances where xenon atoms or pairs are trapped by the crystalline lattice of another compound. One example is xenon hydrate (Xe·5+3⁄4H2O), where xenon atoms occupy vacancies in a lattice of water molecules.[125] This clathrate has a melting point of 24 °C.[126] The deuterated version of this hydrate has also been produced.[127] Another example is xenon hydride (Xe(H2)8), in which xenon pairs (dimers) are trapped inside solid hydrogen.[128] Such clathrate hydrates can occur naturally under conditions of high pressure, such as in Lake Vostok underneath the Antarctic ice sheet.[129] Clathrate formation can be used to fractionally distill xenon, argon and krypton.[130]

Xenon can also form endohedral fullerene compounds, where a xenon atom is trapped inside a fullerene molecule. The xenon atom trapped in the fullerene can be observed by 129Xe nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Through the sensitive chemical shift of the xenon atom to its environment, chemical reactions on the fullerene molecule can be analyzed. These observations are not without caveat, however, because the xenon atom has an electronic influence on the reactivity of the fullerene.[131]

When xenon atoms are in the ground energy state, they repel each other and will not form a bond. When xenon atoms becomes energized, however, they can form an excimer (excited dimer) until the electrons return to the ground state. This entity is formed because the xenon atom tends to complete the outermost electronic shell by adding an electron from a neighboring xenon atom. The typical lifetime of a xenon excimer is 1–5 nanoseconds, and the decay releases photons with wavelengths of about 150 and 173 nm.[132][133] Xenon can also form excimers with other elements, such as the halogens bromine, chlorine, and fluorine.[134]

Applications

Although xenon is rare and relatively expensive to extract from the Earth's atmosphere, it has a number of applications.

Gas-discharge lamps

Xenon is used in light-emitting devices called xenon flash lamps, used in photographic flashes and stroboscopic lamps;[17] to excite the active medium in lasers which then generate coherent light;[135] and, occasionally, in bactericidal lamps.[136] The first solid-state laser, invented in 1960, was pumped by a xenon flash lamp,[21] and lasers used to power inertial confinement fusion are also pumped by xenon flash lamps.[137]

Continuous, short-arc, high pressure xenon arc lamps have a color temperature closely approximating noon sunlight and are used in solar simulators. That is, the chromaticity of these lamps closely approximates a heated black body radiator at the temperature of the Sun. First introduced in the 1940s, these lamps replaced the shorter-lived carbon arc lamps in movie projectors.[18] They are also employed in typical 35mm, IMAX, and digital film projection systems. They are an excellent source of short wavelength ultraviolet radiation and have intense emissions in the near infrared used in some night vision systems. Xenon is used as a starter gas in metal halide lamps for automotive HID headlights, and high-end "tactical" flashlights.

The individual cells in a plasma display contain a mixture of xenon and neon ionized with electrodes. The interaction of this plasma with the electrodes generates ultraviolet photons, which then excite the phosphor coating on the front of the display.[138][139]

Xenon is used as a "starter gas" in high pressure sodium lamps. It has the lowest thermal conductivity and lowest ionization potential of all the non-radioactive noble gases. As a noble gas, it does not interfere with the chemical reactions occurring in the operating lamp. The low thermal conductivity minimizes thermal losses in the lamp while in the operating state, and the low ionization potential causes the breakdown voltage of the gas to be relatively low in the cold state, which allows the lamp to be more easily started.[140]

Lasers

In 1962, a group of researchers at Bell Laboratories discovered laser action in xenon,[141] and later found that the laser gain was improved by adding helium to the lasing medium.[142][143] The first excimer laser used a xenon dimer (Xe2) energized by a beam of electrons to produce stimulated emission at an ultraviolet wavelength of 176 nm.[20] Xenon chloride and xenon fluoride have also been used in excimer (or, more accurately, exciplex) lasers.[144]

Anesthesia

Xenon has been used as a general anesthetic, but it is more expensive than conventional anesthetics.[145]

Xenon interacts with many different receptors and ion channels, and like many theoretically multi-modal inhalation anesthetics, these interactions are likely complementary. Xenon is a high-affinity glycine-site NMDA receptor antagonist.[146] However, xenon is different from certain other NMDA receptor antagonists in that it is not neurotoxic and it inhibits the neurotoxicity of ketamine and nitrous oxide (N2O), while actually producing neuroprotective effects.[147][148] Unlike ketamine and nitrous oxide, xenon does not stimulate a dopamine efflux in the nucleus accumbens.[149]

Like nitrous oxide and cyclopropane, xenon activates the two-pore domain potassium channel TREK-1. A related channel TASK-3 also implicated in the actions of inhalation anesthetics is insensitive to xenon.[150] Xenon inhibits nicotinic acetylcholine α4β2 receptors which contribute to spinally mediated analgesia.[151][152] Xenon is an effective inhibitor of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase. Xenon inhibits Ca2+ ATPase by binding to a hydrophobic pore within the enzyme and preventing the enzyme from assuming active conformations.[153]

Xenon is a competitive inhibitor of the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor. While neither anesthetic nor antinociceptive, this reduces anesthesia-emergent nausea and vomiting.[154]

Xenon has a minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) of 72% at age 40, making it 44% more potent than N2O as an anesthetic.[155] Thus, it can be used with oxygen in concentrations that have a lower risk of hypoxia. Unlike nitrous oxide, xenon is not a greenhouse gas and is viewed as environmentally friendly.[156] Though recycled in modern systems, xenon vented to the atmosphere is only returning to its original source, without environmental impact.

Neuroprotectant

Xenon induces robust cardioprotection and neuroprotection through a variety of mechanisms. Through its influence on Ca2+, K+, KATP\HIF, and NMDA antagonism, xenon is neuroprotective when administered before, during and after ischemic insults.[157][158] Xenon is a high affinity antagonist at the NMDA receptor glycine site.[146] Xenon is cardioprotective in ischemia-reperfusion conditions by inducing pharmacologic non-ischemic preconditioning. Xenon is cardioprotective by activating PKC-epsilon and downstream p38-MAPK.[159] Xenon mimics neuronal ischemic preconditioning by activating ATP sensitive potassium channels.[160] Xenon allosterically reduces ATP mediated channel activation inhibition independently of the sulfonylurea receptor1 subunit, increasing KATP open-channel time and frequency.[161]

Sports doping

Inhaling a xenon/oxygen mixture activates production of the transcription factor HIF-1-alpha, which may lead to increased production of erythropoietin. The latter hormone is known to increase red blood cell production and athletic performance. Reportedly, doping with xenon inhalation has been used in Russia since 2004 and perhaps earlier.[162] On August 31, 2014, the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) added xenon (and argon) to the list of prohibited substances and methods, although no reliable doping tests for these gases have yet been developed.[163] In addition, effects of xenon on erythropoietin production in humans have not been demonstrated, so far.[164]

Imaging

Gamma emission from the radioisotope 133Xe of xenon can be used to image the heart, lungs, and brain, for example, by means of single photon emission computed tomography. 133Xe has also been used to measure blood flow.[165][166][167]

Xenon, particularly hyperpolarized 129Xe, is a useful contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the gas phase, it can image cavities in a porous sample, alveoli in lungs, or the flow of gases within the lungs.[168][169] Because xenon is soluble both in water and in hydrophobic solvents, it can image various soft living tissues.[170][171][172]

Xenon-129 is currently being used as a visualization agent in MRI scans. When a patient inhales hyperpolarized xenon-129 ventilation and gas exchange in the lungs can be imaged and quantified. Unlike xenon-133, xenon-129 is non-ionizing and is safe to be inhaled with no adverse effects.[173]

Surgery

The xenon chloride excimer laser has certain dermatological uses.[174]

NMR spectroscopy

Because of the xenon atom's large, flexible outer electron shell, the NMR spectrum changes in response to surrounding conditions and can be used to monitor the surrounding chemical circumstances. For instance, xenon dissolved in water, xenon dissolved in hydrophobic solvent, and xenon associated with certain proteins can be distinguished by NMR.[175][176]

Hyperpolarized xenon can be used by surface chemists. Normally, it is difficult to characterize surfaces with NMR because signals from a surface are overwhelmed by signals from the atomic nuclei in the bulk of the sample, which are much more numerous than surface nuclei. However, nuclear spins on solid surfaces can be selectively polarized by transferring spin polarization to them from hyperpolarized xenon gas. This makes the surface signals strong enough to measure and distinguish from bulk signals.[177][178]

Other

In nuclear energy studies, xenon is used in bubble chambers,[179] probes, and in other areas where a high molecular weight and inert chemistry is desirable. A by-product of nuclear weapon testing is the release of radioactive xenon-133 and xenon-135. These isotopes are monitored to ensure compliance with nuclear test ban treaties,[180] and to confirm nuclear tests by states such as North Korea.[181]

Liquid xenon is used in calorimeters[182] to measure gamma rays, and as a detector of hypothetical weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs. When a WIMP collides with a xenon nucleus, theory predicts it will impart enough energy to cause ionization and scintillation. Liquid xenon is useful for these experiments because its density makes dark matter interaction more likely and it permits a quiet detector through self-shielding.

Xenon is the preferred propellant for ion propulsion of spacecraft because it has low ionization potential per atomic weight and can be stored as a liquid at near room temperature (under high pressure), yet easily evaporated to feed the engine. Xenon is inert, environmentally friendly, and less corrosive to an ion engine than other fuels such as mercury or caesium. Xenon was first used for satellite ion engines during the 1970s.[183] It was later employed as a propellant for JPL's Deep Space 1 probe, Europe's SMART-1 spacecraft[23] and for the three ion propulsion engines on NASA's Dawn Spacecraft.[184]

Chemically, the perxenate compounds are used as oxidizing agents in analytical chemistry. Xenon difluoride is used as an etchant for silicon, particularly in the production of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS).[185] The anticancer drug 5-fluorouracil can be produced by reacting xenon difluoride with uracil.[186] Xenon is also used in protein crystallography. Applied at pressures from 0.5 to 5 MPa (5 to 50 atm) to a protein crystal, xenon atoms bind in predominantly hydrophobic cavities, often creating a high-quality, isomorphous, heavy-atom derivative that can be used for solving the phase problem.[187][188]

Precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Xenon gas can be safely kept in normal sealed glass or metal containers at standard temperature and pressure. However, it readily dissolves in most plastics and rubber, and will gradually escape from a container sealed with such materials.[190] Xenon is non-toxic, although it does dissolve in blood and belongs to a select group of substances that penetrate the blood–brain barrier, causing mild to full surgical anesthesia when inhaled in high concentrations with oxygen.[191]

The speed of sound in xenon gas (169 m/s) is less than that in air[192] because the average velocity of the heavy xenon atoms is less than that of nitrogen and oxygen molecules in air. Hence, xenon vibrates more slowly in the vocal cords when exhaled and produces lowered voice tones (low-frequency-enhanced sounds, but the fundamental frequency or pitch does not change), an effect opposite to the high-toned voice produced in helium. Specifically, when the vocal tract is filled with xenon gas, its natural resonant frequency becomes lower than when it is filled with air. Thus, the low frequencies of the sound wave produced by the same direct vibration of the vocal cords would be enhanced, resulting in a change of the timbre of the sound amplified by the vocal tract. Like helium, xenon does not satisfy the body's need for oxygen, and it is both a simple asphyxiant and an anesthetic more powerful than nitrous oxide; consequently, and because xenon is expensive, many universities have prohibited the voice stunt as a general chemistry demonstration. The gas sulfur hexafluoride is similar to xenon in molecular weight (146 versus 131), less expensive, and though an asphyxiant, not toxic or anesthetic; it is often substituted in these demonstrations.[193]

Dense gases such as xenon and sulfur hexafluoride can be breathed safely when mixed with at least 20% oxygen. Xenon at 80% concentration along with 20% oxygen rapidly produces the unconsciousness of general anesthesia. Breathing mixes gases of different densities very effectively and rapidly so that heavier gases are purged along with the oxygen, and do not accumulate at the bottom of the lungs.[194] There is, however, a danger associated with any heavy gas in large quantities: it may sit invisibly in a container, and a person who enters an area filled with an odorless, colorless gas may be asphyxiated without warning. Xenon is rarely used in large enough quantities for this to be a concern, though the potential for danger exists any time a tank or container of xenon is kept in an unventilated space.[195]

Water-soluble xenon compounds such as monosodium xenate are moderately toxic, but have a very short half-life of the body – intravenously injected xenate is reduced to elemental xenon in about a minute.[191]

See also

Notes

- Mass fraction calculated from the average mass of an atom in the Solar System of about 1.29 atomic mass units.

References

- "xenon". Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 20 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- "Xenon". Dictionary.com Unabridged. 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Standard Atomic Weights: Xenon". CIAAW. 1999.

- "Xenon". Gas Encyclopedia. Air Liquide. 2009.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.123. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- Hwang, Shuen-Cheng; Weltmer, William R. (2000). "Helium Group Gases". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Wiley. pp. 343–383. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0701190508230114.a01. ISBN 0-471-23896-1.

- Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- "Observation of two-neutrino double electron capture in 124Xe with XENON1T". Nature. 568 (7753): 532–535. 2019. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1124-4.

- Albert, J. B.; Auger, M.; Auty, D. J.; Barbeau, P. S.; Beauchamp, E.; Beck, D.; Belov, V.; Benitez-Medina, C.; Bonatt, J.; Breidenbach, M.; Brunner, T.; Burenkov, A.; Cao, G. F.; Chambers, C.; Chaves, J.; Cleveland, B.; Cook, S.; Craycraft, A.; Daniels, T.; Danilov, M.; Daugherty, S. J.; Davis, C. G.; Davis, J.; Devoe, R.; Delaquis, S.; Dobi, A.; Dolgolenko, A.; Dolinski, M. J.; Dunford, M.; et al. (2014). "Improved measurement of the 2νββ half-life of 136Xe with the EXO-200 detector". Physical Review C. 89. arXiv:1306.6106. Bibcode:2014PhRvC..89a5502A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.89.015502.

- Redshaw, M.; Wingfield, E.; McDaniel, J.; Myers, E. (2007). "Mass and Double-Beta-Decay Q Value of 136Xe". Physical Review Letters. 98 (5): 53003. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98e3003R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.053003.

- "Xenon". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University Press. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- Husted, Robert; Boorman, Mollie (December 15, 2003). "Xenon". Los Alamos National Laboratory, Chemical Division. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- Rabinovich, Viktor Abramovich; Vasserman, A. A.; Nedostup, V. I.; Veksler, L. S. (1988). Thermophysical properties of neon, argon, krypton, and xenon. Bibcode:1988wdch...10.....R. ISBN 0-89116-675-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)—National Standard Reference Data Service of the USSR. Volume 10. - Freemantle, Michael (August 25, 2003). "Chemistry at its Most Beautiful". Chemical & Engineering News. Vol. 81, no. 34. pp. 27–30. doi:10.1021/cen-v081n034.p027.

- Burke, James (2003). Twin Tracks: The Unexpected Origins of the Modern World. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-7432-2619-4.

- Mellor, David (2000). Sound Person's Guide to Video. Focal Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-240-51595-1.

- Sanders, Robert D.; Ma, Daqing; Maze, Mervyn (2005). "Xenon: elemental anaesthesia in clinical practice". British Medical Bulletin. 71 (1): 115–35. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh034. PMID 15728132.

- Basov, N. G.; Danilychev, V. A.; Popov, Yu. M. (1971). "Stimulated Emission in the Vacuum Ultraviolet Region". Soviet Journal of Quantum Electronics. 1 (1): 18–22. Bibcode:1971QuEle...1...18B. doi:10.1070/QE1971v001n01ABEH003011.

- Toyserkani, E.; Khajepour, A.; Corbin, S. (2004). Laser Cladding. CRC Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-8493-2172-7.

- Ball, Philip (May 1, 2002). "Xenon outs WIMPs". Nature. doi:10.1038/news020429-6. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- Saccoccia, G.; del Amo, J. G.; Estublier, D. (August 31, 2006). "Ion engine gets SMART-1 to the Moon". ESA. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- Kaneoka, Ichiro (1998). "Xenon's Inside Story". Science. 280 (5365): 851–852. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.851b. S2CID 128502357.

- Stacey, Weston M. (2007). Nuclear Reactor Physics. Wiley-VCH. p. 213. ISBN 978-3-527-40679-1.

- Ramsay, Sir William (July 12, 1898). "Nobel Lecture – The Rare Gases of the Atmosphere". Nobel prize. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Ramsay, W.; Travers, M. W. (1898). "On the extraction from air of the companions of argon, and neon". Report of the Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science: 828.

- Gagnon, Steve. "It's Elemental – Xenon". Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- Daniel Coit Gilman; Harry Thurston Peck; Frank Moore Colby, eds. (1904). The New International Encyclopædia. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 906.

- The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories. Merriam-Webster. 1991. p. 513. ISBN 0-87779-603-3.

- Ramsay, William (1902). "An Attempt to Estimate the Relative Amounts of Krypton and of Xenon in Atmospheric Air". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 71 (467–476): 421–26. Bibcode:1902RSPS...71..421R. doi:10.1098/rspl.1902.0121. S2CID 97151557.

- "History". Millisecond Cinematography. Archived from the original on 2006-08-22. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- Paschotta, Rüdiger (November 1, 2007). "Lamp-pumped lasers". Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology. RP Photonics. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- Marx, Thomas; Schmidt, Michael; Schirmer, Uwe; Reinelt, Helmut (2000). "Xenon anesthesia" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 93 (10): 513–7. doi:10.1177/014107680009301005. PMC 1298124. PMID 11064688. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

-

Bartlett, Neil; Lohmann, D. H. (1962). "Dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate (V), O+

2[PtF

6]−

". Proceedings of the Chemical Society. London: Chemical Society (3): 115. doi:10.1039/PS9620000097. - Bartlett, N. (1962). "Xenon hexafluoroplatinate (V) Xe+[PtF6]−". Proceedings of the Chemical Society. London: Chemical Society (6): 218. doi:10.1039/PS9620000197.

- Graham, L.; Graudejus, O.; Jha N.K.; Bartlett, N. (2000). "Concerning the nature of XePtF6". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 197 (1): 321–34. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00190-3.

- Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Egon (2001). Bernhard J. Aylett (ed.). Inorganic Chemistry. translated by Mary Eagleson and William Brewer. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.; translation of Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, founded by A. F. Holleman, continued by Egon Wiberg, edited by Nils Wiberg, Berlin: de Gruyter, 1995, 34th edition, ISBN 3-11-012641-9.

- Steel, Joanna (2007). "Biography of Neil Bartlett". College of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- Bartlett, Neil (2003-09-09). "The Noble Gases". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. 81 (36): 32–34. doi:10.1021/cen-v081n036.p032. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- Khriachtchev, Leonid; Pettersson, Mika; Runeberg, Nino; Lundell, Jan; Räsänen, Markku (2000-08-24). "A stable argon compound". Nature. 406 (6798): 874–6. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..874K. doi:10.1038/35022551. PMID 10972285. S2CID 4382128.

- Lynch, C. T.; Summitt, R.; Sliker, A. (1980). CRC Handbook of Materials Science. CRC Press. ISBN 0-87819-231-X.

- MacKenzie, D. R. (1963). "Krypton Difluoride: Preparation and Handling". Science. 141 (3586): 1171. Bibcode:1963Sci...141.1171M. doi:10.1126/science.141.3586.1171. PMID 17751791. S2CID 44475654.

- Paul R. Fields; Lawrence Stein & Moshe H. Zirin (1962). "Radon Fluoride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 84 (21): 4164–65. doi:10.1021/ja00880a048.

- "Xenon". Periodic Table Online. CRC Press. Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- Moody, G. J. (1974). "A Decade of Xenon Chemistry". Journal of Chemical Education. 51 (10): 628–30. Bibcode:1974JChEd..51..628M. doi:10.1021/ed051p628. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Browne, Malcolm W. (April 5, 1990) "2 Researchers Spell 'I.B.M.,' Atom by Atom". New York Times

- Williams, David R. (April 19, 2007). "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- Aprile, Elena; Bolotnikov, Aleksey E.; Doke, Tadayoshi (2006). Noble Gas Detectors. Wiley-VCH. pp. 8–9. ISBN 3-527-60963-6.

- Rentzepis, P. M.; Douglass, D. C. (1981-09-10). "Xenon as a solvent". Nature. 293 (5828): 165–166. Bibcode:1981Natur.293..165R. doi:10.1038/293165a0. S2CID 4237285.

- Caldwell, W. A.; Nguyen, J.; Pfrommer, B.; Louie, S.; Jeanloz, R. (1997). "Structure, bonding and geochemistry of xenon at high pressures". Science. 277 (5328): 930–933. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.930.

- Fontes, E. "Golden Anniversary for Founder of High-pressure Program at CHESS". Cornell University. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Eremets, Mikhail I.; Gregoryanz, Eugene A.; Struzhkin, Victor V.; Mao, Ho-Kwang; Hemley, Russell J.; Mulders, Norbert; Zimmerman, Neil M. (2000). "Electrical Conductivity of Xenon at Megabar Pressures". Physical Review Letters. 85 (13): 2797–800. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.2797E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2797. PMID 10991236. S2CID 19937739.

- Iakoubovskii, Konstantin; Mitsuishi, Kazutaka; Furuya, Kazuo (2008). "Structure and pressure inside Xe nanoparticles embedded in Al". Physical Review B. 78 (6): 064105. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..78f4105I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.064105. S2CID 29156048.

- Bader, Richard F. W. "An Introduction to the Electronic Structure of Atoms and Molecules". McMaster University. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Talbot, John. "Spectra of Gas Discharges". Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen. Archived from the original on July 18, 2007. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- Watts, William Marshall (1904). An Introduction to the Study of Spectrum Analysis. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Hwang, Shuen-Cheng; Robert D. Lein; Daniel A. Morgan (2005). "Noble Gases". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (5th ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0701190508230114.a01. ISBN 0-471-48511-X.

- Lebedev, P. K.; Pryanichnikov, V. I. (1993). "Present and future production of xenon and krypton in the former USSR region and some physical properties of these gases" (PDF). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 327 (1): 222–226. Bibcode:1993NIMPA.327..222L. doi:10.1016/0168-9002(93)91447-U.

- Kerry, Frank G. (2007). Industrial Gas Handbook: Gas Separation and Purification. CRC Press. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-0-8493-9005-0.

- "Xenon – Xe". CFC StarTec LLC. August 10, 1998. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- Häussinger, Peter; Glatthaar, Reinhard; Rhode, Wilhelm; Kick, Helmut; Benkmann, Christian; Weber, Josef; Wunschel, Hans-Jörg; Stenke, Viktor; Leicht, Edith; Stenger, Hermann (2001). "Noble Gases". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (6th ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_485. ISBN 3-527-20165-3.

- Arnett, David (1996). Supernovae and Nucleosynthesis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01147-8.

- Mahaffy, P. R.; Niemann, H. B.; Alpert, A.; Atreya, S. K.; Demick, J.; Donahue, T. M.; Harpold, D. N.; Owen, T. C. (2000). "Noble gas abundance and isotope ratios in the atmosphere of Jupiter from the Galileo Probe Mass Spectrometer". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (E6): 15061–72. Bibcode:2000JGR...10515061M. doi:10.1029/1999JE001224.

- Owen, Tobias; Mahaffy, Paul; Niemann, H. B.; Atreya, Sushil; Donahue, Thomas; Bar-Nun, Akiva; de Pater, Imke (1999). "A low-temperature origin for the planetesimals that formed Jupiter" (PDF). Nature. 402 (6759): 269–70. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..269O. doi:10.1038/46232. hdl:2027.42/62913. PMID 10580497. S2CID 4426771.

- Sanloup, Chrystèle; et al. (2005). "Retention of Xenon in Quartz and Earth's Missing Xenon". Science. 310 (5751): 1174–7. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1174S. doi:10.1126/science.1119070. PMID 16293758. S2CID 31226092.

- Clayton, Donald D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis. University of Chicago Press. p. 604. ISBN 0-226-10953-4.

- Heymann, D.; Dziczkaniec, M. (March 19–23, 1979). Xenon from intermediate zones of supernovae. Proceedings 10th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston, Texas: Pergamon Press, Inc. pp. 1943–1959. Bibcode:1979LPSC...10.1943H.

- Beer, H.; Kaeppeler, F.; Reffo, G.; Venturini, G. (November 1983). "Neutron capture cross-sections of stable xenon isotopes and their application in stellar nucleosynthesis". Astrophysics and Space Science. 97 (1): 95–119. Bibcode:1983Ap&SS..97...95B. doi:10.1007/BF00684613. S2CID 123139238.

- Caldwell, Eric (January 2004). "Periodic Table – Xenon". Resources on Isotopes. USGS. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ""Xenon Poisoning" or Neutron Absorption in Reactors".

- "Chernobyl Appendix 1: Sequence of Events – World Nuclear Association".

- Lee, Seung-Kon; Beyer, Gerd J.; Lee, Jun Sig (2016). "Development of Industrial-Scale Fission 99Mo Production Process Using Low Enriched Uranium Target". Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 48 (3): 613–623. doi:10.1016/j.net.2016.04.006.

- "Novel gas-capture approach advances nuclear fuel management". 24 July 2020.

- "What's in Spent Nuclear Fuel? (After 20 yrs) – Energy from Thorium". 22 June 2010.

- Barabash, A. S. (2002). "Average (Recommended) Half-Life Values for Two-Neutrino Double-Beta Decay". Czechoslovak Journal of Physics. 52 (4): 567–573. arXiv:nucl-ex/0203001. Bibcode:2002CzJPh..52..567B. doi:10.1023/A:1015369612904. S2CID 15146959.

- Aprile, E.; et al. (2019). "Observation of two-neutrino double electron capture in 124Xe with XENON1T". Nature. 568 (7753): 532–535. arXiv:1904.11002. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..532X. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1124-4. PMID 31019319. S2CID 129948831.

- Ackerman, N. (2011). "Observation of Two-Neutrino Double-Beta Decay in 136Xe with the EXO-200 Detector". Physical Review Letters. 107 (21): 212501. arXiv:1108.4193. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107u2501A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.212501. PMID 22181874. S2CID 40334443.

- Otten, Ernst W. (2004). "Take a breath of polarized noble gas". Europhysics News. 35 (1): 16–20. Bibcode:2004ENews..35...16O. doi:10.1051/epn:2004109. S2CID 51224754.

- Ruset, I. C.; Ketel, S.; Hersman, F. W. (2006). "Optical Pumping System Design for Large Production of Hyperpolarized 129Xe". Physical Review Letters. 96 (5): 053002. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96e3002R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.053002. PMID 16486926.

- Wolber, J.; Cherubini, A.; Leach, M. O.; Bifone, A. (2000). "On the oxygenation-dependent 129Xe t1 in blood". NMR in Biomedicine. 13 (4): 234–7. doi:10.1002/1099-1492(200006)13:4<234::AID-NBM632>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 10867702. S2CID 94795359.

- Chann, B.; Nelson, I. A.; Anderson, L. W.; Driehuys, B.; Walker, T. G. (2002). "129Xe-Xe molecular spin relaxation". Physical Review Letters. 88 (11): 113–201. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88k3201C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.113201. PMID 11909399.

- von Schulthess, Gustav Konrad; Smith, Hans-Jørgen; Pettersson, Holger; Allison, David John (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Medical Imaging. Taylor & Francis. p. 194. ISBN 1-901865-13-4.

- Warren, W. W.; Norberg, R. E. (1966). "Nuclear Quadrupole Relaxation and Chemical Shift of Xe131 in Liquid and Solid Xenon". Physical Review. 148 (1): 402–412. Bibcode:1966PhRv..148..402W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.148.402.

- Staff. "Hanford Becomes Operational". The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History. U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2009-12-10. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Pfeffer, Jeremy I.; Nir, Shlomo (2000). Modern Physics: An Introductory Text. Imperial College Press. pp. 421 ff. ISBN 1-86094-250-4.

- Laws, Edwards A. (2000). Aquatic Pollution: An Introductory Text. John Wiley and Sons. p. 505. ISBN 0-471-34875-9.

- Staff (April 9, 1979). "A Nuclear Nightmare". Time. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- Meshik, A. P.; Hohenberg, C. M.; Pravdivtseva, O. V. (2004). "Record of Cycling Operation of the Natural Nuclear Reactor in the Oklo/Okelobondo Area in Gabon". Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (18): 182302. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93r2302M. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.93.182302. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 15525157.

- Clayton, Donald D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-226-10953-4.

- Bolt, B. A.; Packard, R. E.; Price, P. B. (2007). "John H. Reynolds, Physics: Berkeley". The University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- Williams, David R. (September 1, 2004). "Mars Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Schilling, James. "Why is the Martian atmosphere so thin and mainly carbon dioxide?". Mars Global Circulation Model Group. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Zahnle, Kevin J. (1993). "Xenological constraints on the impact erosion of the early Martian atmosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 98 (E6): 10, 899–10, 913. Bibcode:1993JGR....9810899Z. doi:10.1029/92JE02941.

- Boulos, M. S.; Manuel, O.K. (1971). "The xenon record of extinct radioactivities in the Earth". Science. 174 (4016): 1334–6. Bibcode:1971Sci...174.1334B. doi:10.1126/science.174.4016.1334. PMID 17801897. S2CID 28159702.

- Harding, Charlie; Johnson, David Arthur; Janes, Rob (2002). Elements of the p block. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0-85404-690-9.

- Dean H Liskow; Henry F Schaefer III; Paul S Bagus; Bowen Liu (1973). "Probable nonexistence of xenon monofluoride as a chemically bound species in the gas phase". J Am Chem Soc. 95 (12): 4056–57. doi:10.1021/ja00793a042.

- Weeks, James L.; Chernick, Cedric; Matheson, Max S. (1962). "Photochemical Preparation of Xenon Difluoride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 84 (23): 4612–13. doi:10.1021/ja00882a063.

- Streng, L. V.; Streng, A. G. (1965). "Formation of Xenon Difluoride from Xenon and Oxygen Difluoride or Fluorine in Pyrex Glass at Room Temperature". Inorganic Chemistry. 4 (9): 1370–71. doi:10.1021/ic50031a035.

- Tramšek, Melita; Žemva, Boris (December 5, 2006). "Synthesis, Properties and Chemistry of Xenon(II) Fluoride". Acta Chimica Slovenica. 53 (2): 105–16. doi:10.1002/chin.200721209.

- Ogrin, Tomaz; Bohinc, Matej; Silvnik, Joze (1973). "Melting-point determinations of xenon difluoride-xenon tetrafluoride mixtures". Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data. 18 (4): 402. doi:10.1021/je60059a014.

- Scott, Thomas; Eagleson, Mary (1994). "Xenon Compounds". Concise encyclopedia chemistry. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1183. ISBN 3-11-011451-8.

- Proserpio, Davide M.; Hoffmann, Roald; Janda, Kenneth C. (1991). "The xenon-chlorine conundrum: van der Waals complex or linear molecule?". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (19): 7184–89. doi:10.1021/ja00019a014.

- Richardson, Nancy A.; Hall, Michael B. (1993). "The potential energy surface of xenon dichloride". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 97 (42): 10952–54. doi:10.1021/j100144a009.

- Bell, C.F. (2013). Syntheses and Physical Studies of Inorganic Compounds. Elsevier Science. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-48328060-8.

- Cockett, A.H.; Smith, K.C.; Bartlett, N. (2013). The Chemistry of the Monatomic Gases: Pergamon Texts in Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier Science. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-48315736-8.

- Brock, D.S.; Schrobilgen, G.J. (2011). "Synthesis of the missing oxide of xenon, XeO2, and its implications for Earth's missing xenon". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (16): 6265–9. doi:10.1021/ja110618g. PMID 21341650.

- "Chemistry: Where did the xenon go?". Nature. 471 (7337): 138. 2011. Bibcode:2011Natur.471T.138.. doi:10.1038/471138d.

- Zhou, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, Y.; Li, J. (2006). "Formation and Characterization of the XeOO+ Cation in Solid Argon". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (8): 2504–5. doi:10.1021/ja055650n. PMID 16492012.

- Holloway, John H.; Hope, Eric G. (1998). A. G. Sykes (ed.). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry Press. Academic. p. 65. ISBN 0-12-023646-X.

- Henderson, W. (2000). Main group chemistry. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 152–53. ISBN 0-85404-617-8.

- Mackay, Kenneth Malcolm; Mackay, Rosemary Ann; Henderson, W. (2002). Introduction to modern inorganic chemistry (6th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 497–501. ISBN 0-7487-6420-8.

- Smith, D. F. (1963). "Xenon Oxyfluoride". Science. 140 (3569): 899–900. Bibcode:1963Sci...140..899S. doi:10.1126/science.140.3569.899. PMID 17810680. S2CID 42752536.

- "P Block Elements". Chemistry Textbook Part - 1 for Class XII (PDF) (October 2022 ed.). NCERT. p. 204. ISBN 9788174506481.

- Christe, K. O.; Dixon, D. A.; Sanders, J. C. P.; Schrobilgen, G. J.; Tsai, S. S.; Wilson, W. W. (1995). "On the Structure of the [XeOF5]− Anion and of Heptacoordinated Complex Fluorides Containing One or Two Highly Repulsive Ligands or Sterically Active Free Valence Electron Pairs". Inorg. Chem. 34 (7): 1868–1874. doi:10.1021/ic00111a039.

- Christe, K. O.; Schack, C. J.; Pilipovich, D. (1972). "Chlorine trifluoride oxide. V. Complex formation with Lewis acids and bases". Inorg. Chem. 11 (9): 2205–2208. doi:10.1021/ic50115a044.

- Holloway, John H.; Hope, Eric G. (1998). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. Contributor A. G. Sykes. Academic Press. pp. 61–90. ISBN 0-12-023646-X.

- Frohn, H.; Theißen, Michael (2004). "C6F5XeF, a versatile starting material in xenon–carbon chemistry". Journal of Fluorine Chemistry. 125 (6): 981–988. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2004.01.019.

- Goetschel, Charles T.; Loos, Karl R. (1972). "Reaction of xenon with dioxygenyl tetrafluoroborate. Preparation of FXe-BF2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 94 (9): 3018–3021. doi:10.1021/ja00764a022.

- Li, Wai-Kee; Zhou, Gong-Du; Mak, Thomas C. W. (2008). Gong-Du Zhou; Thomas C. W. Mak (eds.). Advanced Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-19-921694-9.

- Li, Wai-Kee; Zhou, Gong-Du; Mak, Thomas C. W. (2008). Advanced Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-19-921694-9.

- Gerber, R. B. (2004). "Formation of novel rare-gas molecules in low-temperature matrices". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 55 (1): 55–78. Bibcode:2004ARPC...55...55G. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.55.091602.094420. PMID 15117247.

- Khriachtchev, Leonid; Isokoski, Karoliina; Cohen, Arik; Räsänen, Markku; Gerber, R. Benny (2008). "A Small Neutral Molecule with Two Noble-Gas Atoms: HXeOXeH". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (19): 6114–8. doi:10.1021/ja077835v. PMID 18407641.

- Pettersson, Mika; Khriachtchev, Leonid; Lundell, Jan; Räsänen, Markku (1999). "A Chemical Compound Formed from Water and Xenon: HXeOH". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 121 (50): 11904–905. doi:10.1021/ja9932784.

- Pauling, L. (1961). "A molecular theory of general anesthesia". Science. 134 (3471): 15–21. Bibcode:1961Sci...134...15P. doi:10.1126/science.134.3471.15. PMID 13733483. Reprinted as Pauling, Linus; Kamb, Barclay, eds. (2001). Linus Pauling: Selected Scientific Papers. Vol. 2. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. pp. 1328–34. ISBN 981-02-2940-2.

- Henderson, W. (2000). Main group chemistry. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 148. ISBN 0-85404-617-8.

- Ikeda, Tomoko; Mae, Shinji; Yamamuro, Osamu; Matsuo, Takasuke; Ikeda, Susumu; Ibberson, Richard M. (November 23, 2000). "Distortion of Host Lattice in Clathrate Hydrate as a Function of Guest Molecule and Temperature". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 104 (46): 10623–30. Bibcode:2000JPCA..10410623I. doi:10.1021/jp001313j.

- Kleppe, Annette K.; Amboage, Mónica; Jephcoat, Andrew P. (2014). "New high-pressure van der Waals compound Kr(H2)4 discovered in the krypton-hydrogen binary system". Scientific Reports. 4: 4989. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4989K. doi:10.1038/srep04989.

- McKay, C. P.; Hand, K. P.; Doran, P. T.; Andersen, D. T.; Priscu, J. C. (2003). "Clathrate formation and the fate of noble and biologically useful gases in Lake Vostok, Antarctica". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (13): 35. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.1702M. doi:10.1029/2003GL017490. S2CID 20136021.

- Barrer, R. M.; Stuart, W. I. (1957). "Non-Stoichiometric Clathrate of Water". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 243 (1233): 172–89. Bibcode:1957RSPSA.243..172B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0213. S2CID 97577041.

- Frunzi, Michael; Cross, R. James; Saunders, Martin (2007). "Effect of Xenon on Fullerene Reactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (43): 13343–6. doi:10.1021/ja075568n. PMID 17924634.

- Silfvast, William Thomas (2004). Laser Fundamentals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83345-0.

- Webster, John G. (1998). The Measurement, Instrumentation, and Sensors Handbook. Springer. ISBN 3-540-64830-5.

- McGhee, Charles; Taylor, Hugh R.; Gartry, David S.; Trokel, Stephen L. (1997). Excimer Lasers in Ophthalmology. Informa Health Care. ISBN 1-85317-253-7.

- Staff (2007). "Xenon Applications". Praxair Technology. Archived from the original on 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- Baltás, E.; Csoma, Z.; Bodai, L.; Ignácz, F.; Dobozy, A.; Kemény, L. (2003). "A xenon-iodine electric discharge bactericidal lamp". Technical Physics Letters. 29 (10): 871–72. Bibcode:2003TePhL..29..871S. doi:10.1134/1.1623874. S2CID 122651818.

- Skeldon, M. D.; Saager, R.; Okishev, A.; Seka, W. (1997). "Thermal distortions in laser-diode- and flash-lamp-pumped Nd:YLF laser rods" (PDF). LLE Review. 71: 137–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2003. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Anonymous. "The plasma behind the plasma TV screen". Plasma TV Science. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- Marin, Rick (March 21, 2001). "Plasma TV: That New Object Of Desire". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- Waymouth, John (1971). Electric Discharge Lamps. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-23048-8.

- Patel, C. K. N.; Bennett Jr., W. R.; Faust, W. L.; McFarlane, R. A. (August 1, 1962). "Infrared spectroscopy using stimulated emission techniques". Physical Review Letters. 9 (3): 102–4. Bibcode:1962PhRvL...9..102P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.9.102.

- Patel, C. K. N.; Faust, W. L.; McFarlane, R. A. (December 1, 1962). "High gain gaseous (Xe-He) optical masers". Applied Physics Letters. 1 (4): 84–85. Bibcode:1962ApPhL...1...84P. doi:10.1063/1.1753707.

- Bennett, Jr., W. R. (1962). "Gaseous optical masers". Applied Optics. 1 (S1): 24–61. Bibcode:1962ApOpt...1S..24B. doi:10.1364/AO.1.000024.

- "Laser Output". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Neice, A. E.; Zornow, M. H. (2016). "Xenon anaesthesia for all, or only a select few?". Anaesthesia. 71 (11): 1259–72. doi:10.1111/anae.13569. PMID 27530275.

- Banks, P.; Franks, N. P.; Dickinson, R. (2010). "Competitive inhibition at the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor mediates xenon neuroprotection against hypoxia-ischemia". Anesthesiology. 112 (3): 614–22. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cea398. PMID 20124979.

- Ma, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Maze, M.; Franks, N. P. (2002). "Neuroprotective and neurotoxic properties of the 'inert' gas, xenon". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 89 (5): 739–46. doi:10.1093/bja/89.5.739. PMID 12393773.

- Nagata, A.; Nakao Si, S.; Nishizawa, N.; Masuzawa, M.; Inada, T.; Murao, K.; Miyamoto, E.; Shingu, K. (2001). "Xenon inhibits but N2O enhances ketamine-induced c-Fos expression in the rat posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 92 (2): 362–368. doi:10.1213/00000539-200102000-00016. PMID 11159233. S2CID 15167421.

- Sakamoto, S.; Nakao, S.; Masuzawa, M.; Inada, T.; Maze, M.; Franks, N. P.; Shingu, K. (2006). "The differential effects of nitrous oxide and xenon on extracellular dopamine levels in the rat nucleus accumbens: a microdialysis study". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 103 (6): 1459–63. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000247792.03959.f1. PMID 17122223. S2CID 1882085.

- Gruss, M.; Bushell, T. J.; Bright, D. P.; Lieb, W. R.; Mathie, A.; Franks, N. P. (2004). "Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane". Molecular Pharmacology. 65 (2): 443–52. doi:10.1124/mol.65.2.443. PMID 14742687. S2CID 7762447.

- Yamakura, T.; Harris, R. A. (2000). "Effects of gaseous anesthetics nitrous oxide and xenon on ligand-gated ion channels. Comparison with isoflurane and ethanol". Anesthesiology. 93 (4): 1095–101. doi:10.1097/00000542-200010000-00034. PMID 11020766. S2CID 4684919.

- Rashid, M. H.; Furue, H.; Yoshimura, M.; Ueda, H. (2006). "Tonic inhibitory role of α4β2 subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on nociceptive transmission in the spinal cord in mice". Pain. 125 (1–2): 125–35. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.011. PMID 16781069. S2CID 53151557.

- Lopez, Maria M.; Kosk-Kosicka, Danuta (1995). "How Do Volatile Anesthetics Inhibit Ca2+-ATPases?". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (47): 28239–245. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.47.28239. PMID 7499320.

- Suzuki, T.; Koyama, H.; Sugimoto, M.; Uchida, I.; Mashimo, T. (2002). "The diverse actions of volatile and gaseous anesthetics on human-cloned 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesiology. 96 (3): 699–704. doi:10.1097/00000542-200203000-00028. PMID 11873047. S2CID 6705116.

- Nickalls, R.W.D.; Mapleson, W.W. (August 2003). "Age-related iso-MAC charts for isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane in man". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 91 (2): 170–74. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg132. PMID 12878613.

- Goto, T.; Nakata Y; Morita S (2003). "Will xenon be a stranger or a friend?: the cost, benefit, and future of xenon anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 98 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1097/00000542-200301000-00002. PMID 12502969. S2CID 19119058.

- Schmidt, Michael; Marx, Thomas; Glöggl, Egon; Reinelt, Helmut; Schirmer, Uwe (May 2005). "Xenon Attenuates Cerebral Damage after Ischemia in Pigs". Anesthesiology. 102 (5): 929–36. doi:10.1097/00000542-200505000-00011. PMID 15851879. S2CID 25266308.

- Dingley, J.; Tooley, J.; Porter, H.; Thoresen, M. (2006). "Xenon Provides Short-Term Neuroprotection in Neonatal Rats When Administered After Hypoxia-Ischemia". Stroke. 37 (2): 501–6. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000198867.31134.ac. PMID 16373643.

- Weber, N. C.; Toma, O.; Wolter, J. I.; Obal, D.; Müllenheim, J.; Preckel, B.; Schlack, W. (2005). "The noble gas xenon induces pharmacological preconditioning in the rat heart in vivo via induction of PKC-epsilon and p38 MAPK". Br J Pharmacol. 144 (1): 123–32. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706063. PMC 1575984. PMID 15644876.

- Bantel, C.; Maze, M.; Trapp, S. (2009). "Neuronal preconditioning by inhalational anesthetics: evidence for the role of plasmalemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels". Anesthesiology. 110 (5): 986–95. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819dadc7. PMC 2930813. PMID 19352153.

- Bantel, C.; Maze, M.; Trapp, S. (2010). "Noble gas xenon is a novel adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel opener". Anesthesiology. 112 (3): 623–30. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cf894a. PMC 2935677. PMID 20179498.

- "Breathe it in". The Economist. 8 February 2014.

- "WADA amends Section S.2.1 of 2014 Prohibited List". 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- Jelkmann, W. (2014). "Xenon Misuse in Sports". Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin/German Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014 (10): 267–71. doi:10.5960/dzsm.2014.143. S2CID 55832101.

- Van Der Wall, Ernst (1992). What's New in Cardiac Imaging?: SPECT, PET, and MRI. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-1615-0.

- Frank, John (1999). "Introduction to imaging: The chest". Student BMJ. 12: 1–44. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- Chandak, Puneet K. (July 20, 1995). "Brain SPECT: Xenon-133". Brigham RAD. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- Albert, M. S.; Balamore, D. (1998). "Development of hyperpolarized noble gas MRI". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 402 (2–3): 441–53. Bibcode:1998NIMPA.402..441A. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(97)00888-7. PMID 11543065.

- Irion, Robert (March 23, 1999). "Head Full of Xenon?". Science News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2004. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- Wolber, J.; Rowland, I. J.; Leach, M. O.; Bifone, A. (1998). "Intravascular delivery of hyperpolarized 129Xenon for in vivo MRI". Applied Magnetic Resonance. 15 (3–4): 343–52. doi:10.1007/BF03162020. S2CID 100913538.

- Driehuys, B.; Möller, H.E.; Cleveland, Z.I.; Pollaro, J.; Hedlund, L.W. (2009). "Pulmonary perfusion and xenon gas exchange in rats: MR imaging with intravenous injection of hyperpolarized 129Xe". Radiology. 252 (2): 386–93. doi:10.1148/radiol.2522081550. PMC 2753782. PMID 19703880.

- Cleveland, Z.I.; Möller, H.E.; Hedlund, L.W.; Driehuys, B. (2009). "Continuously infusing hyperpolarized 129Xe into flowing aqueous solutions using hydrophobic gas exchange membranes". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 113 (37): 12489–99. doi:10.1021/jp9049582. PMC 2747043. PMID 19702286.

- Marshall, Helen; Stewart, Neil J.; Chan, Ho-Fung; Rao, Madhwesha; Norquay, Graham; Wild, Jim M. (2021-02-01). "In vivo methods and applications of xenon-129 magnetic resonance". Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 122: 42–62. doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2020.11.002. ISSN 0079-6565. PMC 7933823. PMID 33632417.

- Baltás, E.; Csoma, Z.; Bodai, L.; Ignácz, F.; Dobozy, A.; Kemény, L. (2006). "Treatment of atopic dermatitis with the xenon chloride excimer laser". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20 (6): 657–60. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01495.x. PMID 16836491. S2CID 20156819.

- Luhmer, M.; Dejaegere, A.; Reisse, J. (1989). "Interpretation of the solvent effect on the screening constant of Xe-129". Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry. 27 (10): 950–52. doi:10.1002/mrc.1260271009. S2CID 95432492.

- Rubin, Seth M.; Spence, Megan M.; Goodson, Boyd M.; Wemmer, David E.; Pines, Alexander (August 15, 2000). "Evidence of nonspecific surface interactions between laser-polarized xenon and myoglobin in solution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 97 (17): 9472–5. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.9472R. doi:10.1073/pnas.170278897. PMC 16888. PMID 10931956.

- Raftery, Daniel; MacNamara, Ernesto; Fisher, Gregory; Rice, Charles V.; Smith, Jay (1997). "Optical Pumping and Magic Angle Spinning: Sensitivity and Resolution Enhancement for Surface NMR Obtained with Laser-Polarized Xenon". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 119 (37): 8746–47. doi:10.1021/ja972035d.

- Gaede, H. C.; Song, Y. -Q.; Taylor, R. E.; Munson, E. J.; Reimer, J. A.; Pines, A. (1995). "High-field cross polarization NMR from laser-polarized xenon to surface nuclei". Applied Magnetic Resonance. 8 (3–4): 373–84. doi:10.1007/BF03162652. S2CID 34971961.

- Galison, Peter Louis (1997). Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. University of Chicago Press. p. 339. ISBN 0-226-27917-0.