Dutasteride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Avodart, others; Combodart, Duodart (with tamsulosin) |

| Other names | GG-745; GI-198745; GI-198745X; N-[2,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-oxo-4-aza-5α-androst-1-ene-17β-carboxamide |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | 5α-Reductase inhibitor |

| Main uses | Enlarged prostate[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 0.5 mg[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603001 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 60%[3] |

| Protein binding | 99%[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4)[3] |

| Metabolites | • 4'-Hydroxydutasteride[3] • 6'-Hydroxydutasteride[3] • 1,2-Dihydrodutasteride[3] (All three active)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–5 weeks[4][5] |

| Excretion | Feces: 40% (metabolites)[3] Urine: 5% (unchanged)[3] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C27H30F6N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 528.539 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Dutasteride, sold under the brand name Avodart among others, is a medication primarily used to treat the symptoms of an enlarged prostate.[1][6] A few months may be required before benefits occur.[6] It is also used for scalp hair loss in men and as a part of hormone therapy in transgender women.[7][8] It is taken by mouth.[1][9]

Common side effects include sexual problems, breast tenderness, and breast enlargement.[1] Other side effects include an increased risk of certain forms of prostate cancer, depression, and angioedema.[1][6] Exposure during pregnancy, including use by the partner of a pregnant women may result in harm to the baby.[1][6] Dutasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor, and hence is a type of antiandrogen.[5] It works by decreasing the production of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), an androgen sex hormone.[10][1]

Dutasteride was patented in 1993 by GlaxoSmithKline and was approved for medical use in 2001.[11][1] It is available as a generic medication.[6] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £12 as of 2019.[6] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about $6.66.[12] In 2017, it was the 276th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[13][14]

Medical uses

Enlarged prostate

Dutasteride is used for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH); colloquially known as an "enlarged prostate".[9][15] It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the U.S. for this indication.[16]

Prostate cancer

A 2010 Cochrane review found a 25–26% reduction in the risk of developing prostate cancer with 5α-reductase inhibitor chemoprevention.[17] However, 5α-reductase inhibitors have been found to increase the risk of developing certain rare but aggressive forms of prostate cancer (27% risk increase), although not all studies have observed this.[18] There is insufficient data to determine if they have an effect on the overall risk of death from prostate cancer.[18]

Scalp hair loss

Dutasteride is approved for the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia in South Korea and Japan at a dosage of 0.5 mg per day.[7][19] It has been found in several studies to improve hair growth in men more rapidly and to a greater extent than 2.5 mg/day finasteride.[7] The superior effectiveness of dutasteride relative to finasteride for this indication is considered to be related to the fact that the inhibition of 5α-reductase and consequent prevention of scalp DHT production is more complete with dutasteride.[3][20] Dutasteride is also used off-label in the treatment of female pattern hair loss.[21][22]

Excessive hair growth

Although no reports specific to dutasteride currently exist,[23][5] 5α-reductase inhibitors like finasteride have been found to be effective in the treatment of hirsutism (excessive facial and/or body hair growth) in women.[5] In a study of 89 women with hyperandrogenism due to persistent adrenarche syndrome, finasteride produced a 93% reduction in facial hirsutism and a 73% reduction in bodily hirsutism after 2 years of treatment.[5] Other studies using finasteride for hirsutism have also found it to be clearly effective.[5] Dutasteride may be more effective than finasteride for this indication due to the fact that its inhibition of the 5α-reductase enzyme is comparatively more complete.[3]

Transgender hormone therapy

Dutasteride is sometimes used as a component of hormone therapy for transgender women in combination with an estrogen and/or another antiandrogen like spironolactone.[8] It may be useful for treating scalp hair loss or in those who have issues tolerating spironolactone.[8]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 0.5 mg by mouth.[2]

Dutasteride is provided in the form of soft oil-filled gelatin by mouth capsules containing 0.5 mg dutasteride.[24]

Side effects

Dutasteride has overall been found to be well tolerated in studies of both men and women, producing minimal side effects.[18] Adverse effects include headache and gastrointestinal discomfort.[18] Isolated reports of menstrual changes, acne, and dizziness also exist.[18] There is a small risk of gynecomastia (breast development or enlargement) in men.[18] The risk of gynecomastia with 5α-reductase inhibitors is about 2.8%.[25]

The FDA has added a warning to dutasteride about an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer.[26] While the potential for positive, negative or neutral changes to the potential risk of developing prostate cancer with dutasteride has not been established, evidence has suggested it may temporarily reduce the growth and prevalence of benign prostate tumors, but could also mask the early detection of prostate cancer. The primary area for concern is for patients who may develop prostate cancer whilst taking dutasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia, which in turn could delay diagnosis and early treatment of the prostate cancer, thereby potentially increasing the risk of these patients developing high-grade prostate cancer.[27] A 2018 meta-analysis found no higher risk of breast cancer with 5α-reductase inhibitors.[28]

Sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction, loss of libido, or reduced semen volume, may occur in 3.4 to 15.8% of men treated with finasteride or dutasteride.[18][29] This is linked to lower quality of life and can cause stress in relationships.[30] It has been reported that in a subset of men, these adverse sexual side effects may persist even after discontinuation of finasteride or dutasteride.[31] Some have decreased sperm numbers as low as 10% of pretreatment values.[32]

Several small studies have reported an association between 5α-reductase inhibitors and depression.[18] However, most studies have not observed this side effect.[18] There have also been reports in a subset of men of long-lasting depression persisting even after discontinuation of dutasteride.[18][31]

Children and people with known significant hypersensitivity (e.g., serious skin reactions, angioedema) to dutasteride should not take dutasteride.[24]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Women who are or who may become pregnant should not handle the drug. Dutasteride can cause birth defects, specifically ambiguous genitalia and undermasculinization, in male babies.[24][33] This is due to its antiandrogenic effects and is seen naturally in 5α-reductase deficiency.[33] As such, women who are pregnant should never take dutasteride.[24] People taking dutasteride should not donate blood to prevent birth defects if a pregnant women receives blood and, due to its long elimination half-life, should also not donate blood for at least 6 months after the cessation of treatment.[24]

Overdose

There is no specific antidote for overdose of dutasteride.[34] Treatment of dutasteride overdose should be based on symptoms and should be supportive.[34] The long elimination half-life of dutasteride should be taken into consideration in the event of an overdose of the medication.[34] Dutasteride has been used in clinical studies at doses of up to 40 mg/day for a week (80 times the therapeutic dosage) and 5 mg/day for 6 months (10 times the therapeutic dosage) with no significant safety concerns or additional side effects, respectively.[34]

Interactions

5α-Reductase inhibitors can also prevent the formation of neurosteroid metabolites like allopregnanolone from progesterone and hence may reduce or block the sedative, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and various other effects of progesterone, particularly in the case of oral progesterone (which is disproportionately converted into these metabolites due to first-pass metabolism).[35][36][37][38][39]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Dutasteride belongs to a class of drugs called 5α-reductase inhibitors, which block the action of the 5α-reductase enzymes that convert testosterone into DHT.[40] It inhibits all three forms of 5α-reductase, and can decrease DHT levels in the blood by up to 98%.[3][41][42] Specifically it is a competitive, mechanism-based (irreversible) inhibitor of all three isoforms of 5α-reductase, types I, II, and III (IC50 values are 3.9 nM for type I and 1.8 nM for type II).[3][41][43][44] This is in contrast to finasteride, which is similarly an irreversible inhibitor of 5α-reductase[44][45] but only inhibits the type II and III isoenzymes.[41] As a result of this difference, dutasteride is able to achieve a reduction in circulating DHT levels of up to 98%, whereas finasteride is able to achieve a reduction of only 65 to 70%.[42][4][40][46] In spite of the differential reduction in circulating DHT levels, the two drugs decrease levels of DHT to a similar extent of approximately 85 to 90% in the prostate gland,[46] where the type II isoform of 5α-reductase predominates.[43]

Since 5α-reductases degrade testosterone to DHT, the inhibition of them could cause an increase in testosterone. However, a 2018 review found that initiation of 5α-reductase inhibitors did not result in a consistent increase in testosterone levels, with some studies showing increases and others showing no change.[47] There was no statistically significant change in testosterone levels from 5α-reductase inhibitors in the overall meta-analysis, though men with lower baseline testosterone levels may a rise in testosterone levels.

In addition to inhibition of DHT production, 5α-reductase inhibitors like dutasteride are also neurosteroidogenesis inhibitors, preventing the 5α-reductase-mediated biosynthesis of various neurosteroids including allopregnanolone (from progesterone), THDOC (from deoxycorticosterone), and 3α-androstanediol (from testosterone).[48] These neurosteroids are potent positive allosteric modulators of the GABAA receptor and have been found to possess antidepressant, anxiolytic, and pro-sexual effects in animal research.[48][49][50] For this reason, prevention of neurosteroid formation may be involved in the sexual dysfunction and depression that has been associated with 5α-reductase inhibitors like dutasteride.[48]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of dutasteride is approximately 60%.[3] Food does not adversely affect the absorption of dutasteride.[3] Peak plasma levels occur 2 to 3 hours after administration.[3] Levels of dutasteride in semen have been found to be 3 ng/mL, with no significant effects on DHT levels in sexual partners.[3] The drug is extensively metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4.[3] It has three major metabolites, including 6'-hydroxydutasteride, 4'-hydroxydutasteride, and 1,2-dihydrodutasteride; the former two are formed by CYP3A4, while the latter is not.[3] All three metabolites are active; 6'-hydroxydutasteride has similar potency as a 5α-reductase inhibitor to dutasteride, while the other two are less potent.[3] Dutasteride has an extremely long terminal or elimination half-life of about 4 or 5 weeks.[4][5] The elimination half-life of dutasteride is increased in the elderly (170 hours for men age 20–49 years, 300 hours for men age >70 years).[3] No dosage adjustment is necessary in the elderly nor in renal impairment.[3] Because of its long elimination half-life, dutasteride remains in the body for a long time after discontinuation and can be detected for up to 4 to 6 months.[3][4] In contrast to dutasteride, finasteride has a short terminal half-life of only 5 to 8 hours.[5][3] Dutasteride is eliminated mainly in the feces (40%) as metabolites.[3] A small portion (5%) is eliminated unchanged in the urine.[3]

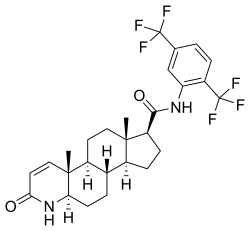

Chemistry

Dutasteride, also known as N-[2,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-oxo-4-aza-5α-androst-1-ene-17β-carboxamide, is a synthetic androstane steroid and a 4-azasteroid.[51][52] It is an analogue of finasteride in which the tert-butyl amide moiety has been replaced with a 2,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl group.[52]

History

Dutasteride was patented in 1996[53] and was first described in the scientific literature in 1997.[54] It was approved by the FDA for the treatment of BPH in November 2001 and was introduced into the United States market the following year under the brand name Avodart.[54] Dutasteride has subsequently been introduced in many other countries, including throughout Europe and South America.[54] The patent protection of dutasteride expired in November 2015 and the drug has since become available in the United States in a variety of low-cost generic formulations.[53]

It was approved for the treatment of scalp hair loss in South Korea since 2009 and in Japan since 2015.[55] It has not been approved for this indication in the United States,[7][19] though it is often used off-label.[21]

Society and culture

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £12 as of 2019.[6] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about $6.66.[12] In 2017, it was the 276th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[13][14]

.svg.png.webp) Dutasteride costs (US)

Dutasteride costs (US).svg.png.webp) Dutasteride prescriptions (US)

Dutasteride prescriptions (US)

Generic names

Dutasteride is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, and JAN.[56]

Brand names

Dutasteride is sold primarily under the brand name Avodart and, in combination with tamsulosin (see dutasteride/tamsulosin), under the brand names Combodart and Duodart.[56] It is also sold under a variety of generic brand names.[56] Dutasteride is also available in combination with alfuzosin under the brand names Alfusin-D and Dutalfa, but only in India.[56]

Availability

Dutasteride is available widely throughout the world, including in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, many other European countries, Australia, and South Africa, as well as in Latin America, Asia, and elsewhere.[56] It is available as a generic medication in the United States and other countries.[53]

Research

Dutasteride has been studied in combination with bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer.[57][58][59][60][61] A study found that dutasteride, which blocks the formation of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone from progesterone, is effective in reducing symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[35]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Dutasteride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1286–1287. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacqueline Burchum; Laura Rosenthal (2 December 2014). Lehne's Pharmacology for Nursing Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 803–. ISBN 978-0-323-34026-7. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ulrike Blume-Peytavi; David A. Whiting; Ralph M. Trüeb (26 June 2008). Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 182, 369. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 769. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 3 4 Jerry Shapiro; Nina Otberg (17 April 2015). Hair Loss and Restoration, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-4822-3199-1. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- 1 2 Wu C, Kapoor A (2013). "Dutasteride for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 14 (10): 1399–408. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.797965. PMID 23750593.

- ↑ Aggarwal S, Thareja S, Verma A, Bhardwaj TR, Kumar M (February 2010). "An overview on 5alpha-reductase inhibitors". Steroids. 75 (2): 109–53. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.005. PMID 19879888.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 483. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Dutasteride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Slater, S; Dumas, C; Bubley, G (March 2012). "Dutasteride for the treatment of prostate-related conditions". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 11 (2): 325–30. doi:10.1517/14740338.2012.658040. PMID 22316171.

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ↑ Wilt TJ, Macdonald R, Hagerty K, Schellhammer P, Tacklind J, Somerfield MR, Kramer BS (2010). "5-α-Reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: an updated Cochrane systematic review". BJU Int. 106 (10): 1444–51. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09714.x. PMID 20977593.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hirshburg JM, Kelsey PA, Therrien CA, Gavino AC, Reichenberg JS (2016). "Adverse Effects and Safety of 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride): A Systematic Review". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 9 (7): 56–62. PMC 5023004. PMID 27672412.

- 1 2 Choi GS, Kim JH, Oh SY, Park JM, Hong JS, Lee YS, Lee WS (2016). "Safety and Tolerability of the Dual 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor Dutasteride in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia". Ann Dermatol. 28 (4): 444–50. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.444. PMC 4969473. PMID 27489426.

- ↑ Ralph M. Trüeb; Won-Soo Lee (13 February 2014). Male Alopecia: Guide to Successful Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-3-319-03233-7. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 Nusbaum AG, Rose PT, Nusbaum BP (2013). "Nonsurgical therapy for hair loss". Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 21 (3): 335–42. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2013.04.003. PMID 24017975.

- ↑ Carmina, Enrico; Azziz, Ricardo; Bergfeld, Wilma; Escobar-Morreale, Héctor F; Futterweit, Walter; Huddleston, Heather; Lobo, Rogerio; Olsen, Elise (2019). "Female Pattern Hair Loss and Androgen Excess: A Report From the Multidisciplinary Androgen Excess and PCOS Committee". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 104 (7): 2875–2891. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02548. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 30785992.

- ↑ Mark G. Lebwohl; Warren R. Heymann; John Berth-Jones; Ian Coulson (19 September 2013). Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 327–. ISBN 978-0-7020-5236-1. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "FDA prescribing information" (PDF). June 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Trost L, Saitz TR, Hellstrom WJ (2013). "Side Effects of 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review". Sex Med Rev. 1 (1): 24–41. doi:10.1002/smrj.3. PMID 27784557.

- ↑ "5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs): Label Change - Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer - U.S. Department of Health & Human Services". Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ↑ Walsh, PC (Apr 1, 2010). "Chemoprevention of prostate cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (13): 1237–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1001045. PMID 20357287.

- ↑ Wang J, Zhao S, Luo L, Li E, Li X, Zhao Z (2018). "5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors and risk of male breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int Braz J Urol. 44 (5): 865–873. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2017.0531. PMC 6237523. PMID 29697934.

- ↑ Liu, L; Zhao, S; Li, F; Li, E; Kang, R; Luo, L; Luo, J; Wan, S; Zhao, Z (September 2016). "Effect of 5α-Reductase Inhibitors on Sexual Function: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (9): 1297–310. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.006. PMID 27475241.

- ↑ Gur, S; Kadowitz, PJ; Hellstrom, WJ (January 2013). "Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors on erectile function, sexual desire and ejaculation". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 12 (1): 81–90. doi:10.1517/14740338.2013.742885. PMID 23173718.

- 1 2 Traish, AM; Hassani, J; Guay, AT; Zitzmann, M; Hansen, ML (March 2011). "Adverse side effects of 5α-reductase inhibitors therapy: persistent diminished libido and erectile dysfunction and depression in a subset of patients". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (3): 872–84. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02157.x. PMID 21176115.

- ↑ Drobnis, Erma Z.; Nangia, Ajay K. (2017). Impacts of Medications on Male Fertility. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1034. pp. 59–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69535-8_7. ISBN 978-3-319-69534-1. ISSN 0065-2598. PMID 29256127.

- 1 2 Kevin T. McVary; Charles Welliver (12 August 2016). Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current methods, outcomes, and controversies, An Issue of Urologic Clinics of North America, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 396–. ISBN 978-0-323-45994-5. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Prescribing information" (PDF). www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-03. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- 1 2 Pearlstein T (2016). "Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Therapeutic Challenges". Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 9 (4): 1–4. doi:10.1586/17512433.2016.1142371. PMID 26766596.

A recent study with a 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride, that blocks the conversion of progesterone to ALLO, reported that dutasteride 2.5 mg daily decreased several premenstrual symptoms [7].

- ↑ Goletiani NV, Keith DR, Gorsky SJ (2007). "Progesterone: review of safety for clinical studies". Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 15 (5): 427–44. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.427. PMID 17924777.

- ↑ Wang-Cheng, Rebekah; Neuner, Joan M.; Barnabei, Vanessa M. (2007). Menopause. ACP Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-930513-83-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- ↑ Bergemann, Niels; Ariecher-Rössler, Anita (27 December 2005). Estrogen Effects in Psychiatric Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 179. ISBN 978-3-211-27063-9. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Bäckström T, Bixo M, Johansson M, Nyberg S, Ossewaarde L, Ragagnin G, Savic I, Strömberg J, Timby E, van Broekhoven F, van Wingen G (2014). "Allopregnanolone and mood disorders". Prog. Neurobiol. 113: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.005. PMID 23978486.

- 1 2 David G. Bostwick; Liang Cheng (24 January 2014). Urologic Surgical Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 492–. ISBN 978-0-323-08619-6. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 Yamana K, Labrie F, Luu-The V (January 2010). "Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride". Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2 (3): 293–9. doi:10.1515/hmbci.2010.035. PMID 25961201.

- 1 2 Rob Bradbury (30 January 2007). Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-3-540-33120-9. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- 1 2 Keam SJ, Scott LJ (2008). "Dutasteride: a review of its use in the management of prostate disorders". Drugs. 68 (4): 463–85. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868040-00008. PMID 18318566.

- 1 2 Gisleskog PO, Hermann D, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Karlsson MO (1998). "A model for the turnover of dihydrotestosterone in the presence of the irreversible 5 alpha-reductase inhibitors GI198745 and finasteride". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 64 (6): 636–47. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90054-6. PMID 9871428.

- ↑ György Keserü; David C. Swinney (28 July 2015). Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Drug Binding. Wiley. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-3-527-67304-9.

- 1 2 John Heesakkers; Christopher Chapple; Dirk De Ridder; Fawzy Farag (24 February 2016). Practical Functional Urology. Springer. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-3-319-25430-2. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Traish, Abdulmaged M.; Krakowsky, Yonah; Doros, Gheorghe; Morgentaler, Abraham (2019). "Do 5α-Reductase Inhibitors Raise Circulating Serum Testosterone Levels? A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis to Explaining Paradoxical Results". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 7 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.06.002. ISSN 2050-0521. PMID 30098986.

- 1 2 3 Traish AM, Mulgaonkar A, Giordano N (2014). "The dark side of 5α-reductase inhibitors' therapy: sexual dysfunction, high Gleason grade prostate cancer and depression". Korean J Urol. 55 (6): 367–79. doi:10.4111/kju.2014.55.6.367. PMC 4064044. PMID 24955220.

- ↑ Abraham Weizman (1 February 2008). Neuroactive Steroids in Brain Function, Behavior and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Novel Strategies for Research and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6854-6.

- ↑ Tvrdeić, Ante; Poljak, Ljiljana (2016). "Neurosteroids, GABAA receptors and neurosteroid based drugs: are we witnessing the dawn of the new psychiatric drugs?". Endocrine Oncology and Metabolism. 2 (1): 60–71. doi:10.21040/eom/2016.2.7. ISSN 1849-8922.

- ↑ Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1381–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 Enrique Ravina (11 January 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- 1 2 3 "Generic Avodart Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- 1 2 3 William Llewellyn (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 968–, 971–. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- ↑ MacDonald, Gareth. "GSK Japan delays alopecia drug launch after Catalent manufacturing halt". Archived from the original on 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Dutasteride". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-11. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- ↑ Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Galbreath RW, Allen ZA, Kurko B (2006). "Efficacy of neoadjuvant bicalutamide and dutasteride as a cytoreductive regimen before prostate brachytherapy". Urology. 68 (1): 116–20. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.061. PMID 16844453.

- ↑ Sartor O, Gomella LG, Gagnier P, Melich K, Dann R (2009). "Dutasteride and bicalutamide in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: the Therapy Assessed by Rising PSA (TARP) study rationale and design". The Canadian Journal of Urology. 16 (5): 4806–12. PMID 19796455.

- ↑ Chu FM, Sartor O, Gomella L, Rudo T, Somerville MC, Hereghty B, Manyak MJ (2015). "A randomised, double-blind study comparing the addition of bicalutamide with or without dutasteride to GnRH analogue therapy in men with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer". European Journal of Cancer. 51 (12): 1555–69. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.028. PMID 26048455.

- ↑ Gaudet M, Vigneault É, Foster W, Meyer F, Martin AG (2016). "Randomized non-inferiority trial of Bicalutamide and Dutasteride versus LHRH agonists for prostate volume reduction prior to I-125 permanent implant brachytherapy for prostate cancer". Radiotherapy and Oncology : Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 118 (1): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.022. PMID 26702991.

- ↑ Dijkstra S, Witjes WP, Roos EP, Vijverberg PL, Geboers AD, Bruins JL, Smits GA, Vergunst H, Mulders PF (2016). "The AVOCAT study: Bicalutamide monotherapy versus combined bicalutamide plus dutasteride therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the prostate-a long-term follow-up comparison and quality of life analysis". SpringerPlus. 5: 653. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2280-8. PMC 4870485. PMID 27330919.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- Frye, S. (2006). "Discovery and Clinical Development of Dutasteride, a Potent Dual 5α- Reductase Inhibitor". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (5): 405–21. doi:10.2174/156802606776743101. PMID 16719800.