Spontaneous coronary artery dissection

| Spontaneous coronary artery dissection | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Coronary artery dissection | |

| |

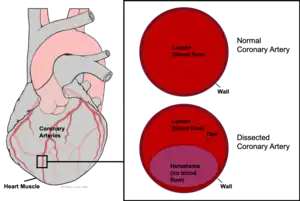

| Coronary artery dissection involves the formation of a false opening which fills with blood (purple) within the walls of a coronary artery. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Chest pain, shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, increased heart enzymes[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure, sudden death[1] |

| Usual onset | Young and middle aged women[1] |

| Risk factors | Pregnancy, fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disorders, inflammatory conditions[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Angiography[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other causes of acute coronary syndrome, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy[1] |

| Treatment | Conservative, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG)[1] |

| Medication | Beta blockers, aspirin[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally good[1] |

| Frequency | Uncommon[1] |

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is when one of the arteries that supply the heart develops a separation within it wall that fills with blood.[1] Symptoms are those of a heart attack, with chest pain, shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, and increased heart enzymes.[1] Complications can include heart failure and sudden death.[1]

Risk factors such as pregnancy, fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disorders, and inflammatory conditions, are often present.[1] Triggers may include vomiting, coughing, or emotional stress.[1] The underlying mechanism involves a tear in the inner lining of an artery that supplies the heart, allowing blood to enter and separate the layers of the wall of the artery.[1] This narrows the artery resulting in decrease blood flow.[1] Diagnosis is usually by angiography, though a number of other types of medical imaging may be used.[1]

The best way to manage the condition is not entirely clear.[1] Conservative treatment is generally preferred over percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG).[1] Beta blockers and aspirin may be recommended long-term.[1] While the risk of death is less than 5%, some type of surgery is required in 15%, and about 10% recur.[1]

SCAD is uncommon.[1] It is estimated to represent between 0.1% and 4% of acute coronary syndrome cases.[1][2] Young and middle aged women are most commonly affected.[1] It was first described in 1931 during an autopsy.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

SCAD often presents like a heart attack in young to middle-aged, healthy women.[4] This pattern usually includes chest pain, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, sweating, extreme tiredness, nausea, and dizziness.[5] A minority of people with SCAD may also present in cardiogenic shock (2-5%), ventricular arrhythmias (3-11%), or after sudden cardiac death.[6] Pregnancy- and postpartum-associated SCAD generally have worse outcomes compared to other cases.[6]

Causes

Risk factors include pregnancy and the postpartum period. Evidence suggests that estrogen- and progesterone-related vascular changes affect the coronary arteries during this period, contributing to SCAD.[6] Some case reports and case series suggest associations with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, but there have not been larger studies to explore this relationship.[6] Underlying heritable conditions such as fibromuscular dysplasia and connective-tissue disorders (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and Loeys–Dietz syndrome) are associated with SCAD,[7] but SCAD otherwise lacks a significant genetic component.[6] SCAD triggers may include severe physical or emotional stress, but many cases have no obvious cause.[8][9]

Other causes of coronary artery dissection include trauma and certain medical procedures.[1]

Pathophysiology

SCAD symptoms are the result of a restriction in the size of the affected coronary artery. The dissection leads to a collection of blood, or hematoma, between the layers of the artery wall. The hematoma does not carry oxygen to the heart muscle but instead forms a "false lumen" that restricts the flow of blood through the "true lumen" to the heart muscle. As yet, there is no consensus on why the hematoma develops in the first place.[10][11][12]

The restriction limits the availability of oxygen and nutrients to the heart muscle, or myocardium. As a result, the myocardium continues to demand oxygen but is not adequately supplied by the coronary artery. This imbalance leads to ischemia, damage, and eventually death of myocardium, causing a heart attack (myocardial infarction). Heart attacks can classically present as chest pain or pressure, shortness of breath, pain in the upper abdomen, and a radiating pain extending along the left arm or the left side of the neck.

Diagnosis

Given the demographics of SCAD, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for the condition in otherwise low-risk women presenting with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome. Initial evaluation may show ECG changes of ST elevation, like heart attacks due to other causes. SCAD comprises 2-4% of all cases of acute coronary syndrome.[13]

With typically elevated cardiac biomarkers and ECG changes, people will often undergo coronary angiography evaluation.[6][14][15] It is important to recognize SCAD through angiography as other confirmatory measures carry increased risks.[16]

Angiography

Angiographic appearances of SCAD fall into three categories.[13] Type 1 lesions appear as classic angiographic dissections, with a false lumen distinct from the true lumen. These are the easiest to identify as SCAD clinically, though relatively uncommon.[13] Type 2 lesions - the most common subtype of SCAD - appear as a long, smooth narrowing of the vessel without a distinctly visible false and true lumen.[6] Type 3 lesions appear similar to atherosclerotic lesions and are difficult to confirm as SCAD through angiography alone,[16] possibly requiring the use of intracoronary imaging.

Angiographic image-contrast was seen to swirl and stay longer than usual, consistent with self-limiting spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Angiographic image-contrast was seen to swirl and stay longer than usual, consistent with self-limiting spontaneous coronary artery dissection This is a representative video of coronary angiography. While it does not display SCAD, it highlights the technique used to identify the condition.

This is a representative video of coronary angiography. While it does not display SCAD, it highlights the technique used to identify the condition.

Intracoronary imaging

Intracoronary imaging (ICI), consisting of intracoronary optical coherence tomography (OCT) and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can help distinguish SCAD from an atherosclerotic lesion when it is difficult to do so with angiography.[17] ICI techniques provide a direct view of the walls of the coronary artery to confirm SCAD, but may actually worsen the dissection as the probes are inserted into the damaged area.[6] ICI confers a 3.4% risk of iatrogenic dissection in people with SCAD compared to 0.2% risk in the general population.[6] Between the two ICI methods, OCT - a newer technique - has superior spatial resolution than IVUS and is the preferred technique if ICI is required,[6] but the need to inject extra contrast with OCT poses risk for worsening the dissection.[13]

Other methods

Some studies propose coronary CT angiography to evaluate SCAD in lower-risk people, with research into the approach ongoing.[6][16]

Management

Management depends upon the presenting symptoms. In most people who are hemodynamically stable without high-risk coronary involvement, conservative medical management with blood pressure control is recommended.[6][18][19] In these people, especially if angiography demonstrates adequate coronary flow, the most likely course usually leads to spontaneous healing, often within 30 days.[20]

In cases involving high-risk coronaries, hemodynamic instability, or a lack of improvement or worsening after initial attempts at treatment, urgent treatment with coronary stents or coronary artery bypass surgery may be necessary.[16] Stents carry the risk of worsening the dissection or have an increased risk of other complications as the vessel walls in SCAD are already weak due to the disease before introducing the stent.[6] Large studies into coronary artery bypass surgery are lacking, but this approach is used to redirect blood to the heart around the affected area for cases involving the left main coronary artery or when other approaches fail.[6][21][22]

After addressing the SCAD, people are often treated with typical post-heart attack care, though people who are pregnant may need altered therapy due to the possibility of some teratogenic cardiac medications affecting fetal development.[16] Depending on the clinical situation, providers may screen for associated connective tissue diseases.[16]

Prognosis

People with SCAD have a low in-hospital mortality after treatment. However, the lesion may worsen after leaving the hospital within the first month.[16][23] One study suggested a 1.2% mortality rate following SCAD but a 19.9% risk for either death, heart attacks, or strokes.[24] Even afterwards, SCAD has a high recurrence risk at 30% within 10 years, often at a different site than the initial lesion - meaning that stents placed in the location of the first lesion may not protect against a second.[16] Given the lack of consensus on the cause of SCAD, prevention of future SCAD may include medical therapy, counseling about becoming pregnant again (for those who had pregnancy-associated SCAD), or avoidance of oral contraceptives - as they contain estrogen and progesterone.

Epidemiology

SCAD is the most common cause of heart attacks in pregnant and postpartum women. Over 90% of people who develop SCAD are women.[23] It is especially common among women aged 43–52.[16] With angiography and improved recognition of the condition, diagnosis of SCAD has improved since the early 2010s. While prior studies had reported a SCAD prevalence of less than 1% in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome, more recent data suggests the prevalence of SCAD in acute coronary syndrome patients may be between 2-4%.[25]

History

SCAD was first described in the year 1931, at a postmortem examination in a 42-year-old woman.[3][25] Due to a lack of recognition and diagnostic technology though, SCAD literature until the 21st century included only case reports and series.[25] With the advent of coronary angiography and intracoronary imaging, recognition and diagnosis of SCAD greatly increased, especially in the 2010s.[25]

See also

- Aortic dissection, a similar condition affecting a different artery

- Kounis syndrome

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Parekh, JD; Chauhan, S; Porter, JL (January 2021). "Coronary Artery Dissection". PMID 29083832.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Yip, A; Saw, J (February 2015). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection-A review". Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 5 (1): 37–48. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.01.08. PMID 25774346.

- 1 2 Pretty HC (18 April 1931). "Dissecting aneurysm of coronary artery in a woman aged 42". British Medical Journal. 1 (3667): 667. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3667.667.

- ↑ ""Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Postpartum"". Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ↑ "Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hayes, Sharonne N.; Kim, Esther S.H.; Saw, Jacqueline; Adlam, David; Arslanian-Engoren, Cynthia; Economy, Katherine E.; Ganesh, Santhi K.; Gulati, Rajiv; Lindsay, Mark E.; Mieres, Jennifer H.; Naderi, Sahar; Shah, Svati; Thaler, David E.; Tweet, Marysia S.; Wood, Malissa J. (8 May 2018). "Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science". Circulation. 137 (19): e523–e557. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564. PMC 5957087. PMID 29472380.

- ↑ Dhawan R, Singh G, Fesniak H. (2002) "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: the clinical spectrum". Angiology

- ↑ Mark V. Sherrid; Jennifer Mieres; Allen Mogtader; Naresh Menezes; Gregory Steinberg (1995) "Onset During Exercise of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection and Sudden Death. Occurrence in a Trained Athlete: Case Report and Review of Prior Cases" Chest

- ↑ {http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/spontaneous-coronary-artery-dissection/basics/risk-factors/con-20037794} Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Virmani R, Forman MB, Rabinowitz M, McAllister HA (1984) "Coronary artery dissections" Cardiol Clinics

- ↑ Kamineni R, Sadhu A, Alpert JS. (2002) "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Report of two cases and 50-year review of the literature" Cardiol Rev

- ↑ Kamran M, Guptan A, Bogal M (October 2008). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: case series and review". The Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 20 (10): 553–9. PMID 18830003.

- 1 2 3 4 Macaya, Fernando; Salinas, Pablo; Gonzalo, Nieves; Fernández-Ortiz, Antonio; Macaya, Carlos; Escaned, Javier (5 November 2018). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: contemporary aspects of diagnosis and patient management". Open Heart. 5 (2): e000884. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2018-000884. PMC 6241978. PMID 30487978.

- ↑ C. Basso, G. L. Morgagni, G. Thiene (1996) "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a neglected cause of acute myocardial ischaemia and sudden death" BMJ

- ↑ Desseigne P, Tabib A, Loire R (July 1992). "[An unusual cause of sudden death: spontaneous dissection of coronary arteries. Apropos of 2 cases]". Archives des Maladies du Coeur et des Vaisseaux. 85 (7): 1031–3. PMID 1449336.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Franke, Kyle B.; Wong, Dennis T. L.; Baumann, Angus; Nicholls, Stephen J.; Gulati, Rajiv; Psaltis, Peter J. (2019). "Current state-of-play in spontaneous coronary artery dissection". Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 9 (3): 281–298. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.04.03. PMC 6603494. PMID 31275818.

- ↑ "Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging in the Diagnosis and Treatment: The Future: IVUS-Guided DES Implantation?". Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ↑ "Coronary Artery Dissection: Not Just a Heart Attack". www.heart.org. Archived from the original on 2018-11-08. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ↑ "SCAD: Not Your Typical Heart Attack". Archived from the original on 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ↑ Alfonso F, Paulo M, Lennie V, Dutary J, Bernardo E, Jiménez-Quevedo P, Gonzalo N, Escaned J, Bañuelos C, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, Hernández R, Macaya C (October 2012). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: long-term follow-up of a large series of patients prospectively managed with a "conservative" therapeutic strategy". JACC. Cardiovascular Interventions. 5 (10): 1062–70. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2012.06.014. PMID 23078737.

- ↑ "MedHelp:Coronary artery dissection treatment". Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ↑ Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJ, Lennon RJ, Lerman A, Rihal CS, Holmes DR, Hayes SN, Gulati R (December 2014). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: revascularization versus conservative therapy". Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 7 (6): 777–86. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001659. PMID 25406203.

- 1 2 Janssen, E. B. N. J.; de Leeuw, P. W.; Maas, A. H. E. M. (2019). "Spontaneous coronary artery dissections and associated predisposing factors: a narrative review". Netherlands Heart Journal. 27 (5): 246–251. doi:10.1007/s12471-019-1235-4. PMC 6470242. PMID 30684142.

- ↑ Saw, Jacqueline; Humphries, Karin; Aymong, Eve; Sedlak, Tara; Prakash, Roshan; Starovoytov, Andrew; Mancini, G. B. John (29 August 2017). "Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Clinical Outcomes and Risk of Recurrence". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (9): 1148–1158. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.053. PMID 28838364.

- 1 2 3 4 Saw, Jacqueline; Mancini, G. B. John; Humphries, Karin H. (19 July 2016). "Contemporary Review on Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 68 (3): 297–312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.034. PMID 27417009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- "Spontaneous-Coronary-Artery-Dissection-Case-Series-and-Review" Archived 2012-04-20 at the Wayback Machine