Hydralazine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Apresoline, BiDil, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Vasodilator[1] |

| Main uses | High blood pressure (including in pregnancy)[2][1] |

| Side effects | Headache, fast heart rate[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, intravenous |

| Onset of action | 5 to 30 min[1] |

| Duration of action | 2 to 6 hrs[1] |

| Defined daily dose | 100 mg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682246 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 26–50% |

| Protein binding | 85–90% |

| Metabolism | Liver[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5-3 hours,[4] 7–16 hours (renal impairment) |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Chemical and physical data | |

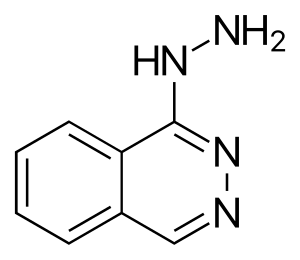

| Formula | C8H8N4 |

| Molar mass | 160.180 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Hydralazine, sold under the brand name Apresoline among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure.[1] This includes high blood pressure in pregnancy and very high blood pressure resulting in symptoms.[5] It has been found to be particularly useful in heart failure, together with isosorbide dinitrate, for treatment of people of African descent.[1] It is given by mouth or by injection into a vein.[5] Effects usually begin around 15 minutes and last up to six hours.[1]

Common side effects include headache and fast heart rate.[1] Rare but serious side effects include peripheral neuropathy and drug fever.[4] It is not recommended in people with coronary artery disease or in those with rheumatic heart disease that affects the mitral valve.[1] In overdose, a lupus-like illness can occur.[4] In those with kidney disease a low dose is recommended.[5] Hydralazine is in the vasodilator family of medications and works by causing the dilation of blood vessels.[4]

Hydralazine was discovered while scientists at Ciba were looking for a treatment for malaria.[6] It was patented in 1949.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$2.78–9.11 per month.[9] In the United States treatment costs about $50–100 per month.[10] In 2017, it was the 105th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than seven million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical use

Hydralazine is not used as a primary drug for treating hypertension because it elicits a reflex sympathetic stimulation of the heart (the baroreceptor reflex).[13] The sympathetic stimulation may increase heart rate and cardiac output, and in people with coronary artery disease may cause angina pectoris or myocardial infarction.[14] Hydralazine may also increase plasma renin concentration, resulting in fluid retention. To prevent these undesirable side effects, hydralazine is usually prescribed in combination with a β-blocker (e.g., propranolol) and a diuretic.[14] Beta-blockers licensed to treat heart failure in the UK include bisoprolol, carvedilol, and nebivolol.

Hydralazine is used to treat severe hypertension, but again, it is not a first-line therapy for essential hypertension. However, hydralazine is often used to treat hypertension in pregnancy, with methyldopa.[15]

Hydralazine is commonly used in combination with isosorbide dinitrate for the treatment of congestive heart failure in self-identified African American populations. This preparation, isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine, was the first race-based prescription drug.[16]

It should not be used in people with tachycardia, heart failure, who have constrictive pericarditis, who have lupus, a dissecting aortic aneurysm, or porphyria.[17]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 100 mg by injection.[3] For high blood pressure in pregnancy it can be given as 5 mg over about 3 minutes by injection into a vein.[2] If after 20 minutes the BP is not improved the dose can be repeated up to 20 mg total.[2] It can also be given as an infusion starting at 200 to 300 micrograms/minute and than decreased to 50 to 150 micrograms/minute.[2]

Side effects

Prolonged treatment may cause a syndrome similar to lupus which can become fatal if the symptoms are not noticed and drug treatment stopped.[17]

Very common (>10% frequency) side effects include headache, high heart rate, and palpitations.[17] Common (1–10% frequency) side effects include flushing, hypotension, anginal symptoms, aching or swelling joints, muscle aches, positive tests for ANP, stomach upset, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, and swelling (sodium and water retention).[17]

Interactions

It may potentiate the antihypertensive effects of:[17]

Drugs subject to a strong first-pass effect such as β-blockers may increase the bioavailability of hydralazine.[17] Epinephrine (adrenaline)'s heart rate-accelerating effects are increased by hydralazine, hence may lead to toxicity.[17]

Mechanism of action

It is a direct-acting smooth muscle relaxant and acts as a vasodilator primarily in resistance arterioles; the molecular mechanism involves inhibition of inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in arterial smooth muscle cells.[18][19] By relaxing vascular smooth muscle, vasodilators act to decrease peripheral resistance, thereby lowering blood pressure and decreasing afterload.[14]

Chemistry

Hydralazine belongs to the hydrazinophthalazine class of drugs.[20]

History

The antihypertensive activity of hydralazine was discovered by scientists at Ciba who were trying to discover drugs to treat malaria; it was initially called C-5968 and 1-hydrazinophthalazine; Ciba's patent application was filed in 1945 and issued in 1949,[21][22][23] and the first scientific publications of its blood-pressure lowering activities appeared in 1950.[6][20][24] It was approved by the FDA in 1953.[25]

It was one of the first antihypertensive medications that could be taken by mouth.[13]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$2.78–9.11 per month.[9] In the United States treatment costs about $50–100 per month.[10] In 2017, it was the 105th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than seven million prescriptions.[11][12]

.svg.png.webp) Hydralazine costs (US)

Hydralazine costs (US).svg.png.webp) Hydralazine prescriptions (US)

Hydralazine prescriptions (US)

Research

Hydralazine has also been studied as a treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome in its capacity as a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Hydralazine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "HYDRALAZINE injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benowitz, Neal L. (2020). "11. Antihypertensive agents". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- 1 2 3 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 280. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 Wermuth CG (2011-05-02). The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780080568775. Archived from the original on 2017-02-26.

- ↑ Progress in Drug Research/Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung/Progrés des recherches pharmaceutiques. Birkhäuser. 2013. p. 206. ISBN 9783034870948. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 1 2 "Hydralazine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 145. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Hydralazine Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 Kandler MR, Mah GT, Tejani AM, Stabler SN, Salzwedel DM (November 2011). "Hydralazine for essential hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD004934. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004934.pub4. PMID 22071816.

- 1 2 3 Harvey, Richard A.; Harvey, Pamela A.; Mycek, Mark J. (2000). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Pharmacology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 190.

- ↑ Bhushan, Vikas; Lee, Tao T.; Ozturk, Ali (2007). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 251.

- ↑ Ferdinand KC, Elkayam U, Mancini D, Ofili E, Piña I, Anand I, et al. (July 2014). "Use of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in African-Americans with heart failure 9 years after the African-American Heart Failure Trial". The American Journal of Cardiology. 114 (1): 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.018. PMID 24846808.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Hydralazine Tablets 50mg". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Gurney AM, Allam M (January 1995). "Inhibition of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit aorta by hydralazine". British Journal of Pharmacology. 114 (1): 238–244. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14931.x. PMC 1510175. PMID 7712024.

- ↑ Ellershaw DC, Gurney AM (October 2001). "Mechanisms of hydralazine induced vasodilation in rabbit aorta and pulmonary artery". British Journal of Pharmacology. 134 (3): 621–631. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704302. PMC 1572994. PMID 11588117.

- 1 2 Schroeder NA (January 1952). "The effect of 1-hydrasinophthalasine in hypertension". Circulation. 5 (1): 28–37. doi:10.1161/01.cir.5.1.28. PMID 14896450.

- ↑ "Hydralazine". Drugbank. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ "hydralazine". PubChem. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ US2484029 Archived 2021-04-30 at the Wayback Machine; see Example 1

- ↑ Reubi FC (January 1950). "Renal hyperemia induced in man by a new phthalazine derivative". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 73 (1): 102–103. doi:10.3181/00379727-73-17591. PMID 15402536.

- ↑ "New Drug Application (NDA) 008303 Company: NOVARTIS Drug Name(s): Apresoline". FDA. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ Singh V, Sharma P, Capalash N (May 2013). "DNA methyltransferase-1 inhibitors as epigenetic therapy for cancer". Current Cancer Drug Targets. 13 (4): 379–99. doi:10.2174/15680096113139990077. PMID 23517596.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |