Francisella tularensis

| Francisella tularensis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Francisella tularensis bacteria (blue) infecting a macrophage (yellow) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Thiotrichales |

| Family: | Francisellaceae |

| Genus: | Francisella |

| Species: | F. tularensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Francisella tularensis (McCoy and Chapin 1912) Dorofe'ev 1947 | |

Francisella tularensis is a pathogenic species of Gram-negative coccobacillus, an aerobic bacterium.[1] It is nonspore-forming, nonmotile,[2] and the causative agent of tularemia, the pneumonic form of which is often lethal without treatment. It is a fastidious, facultative intracellular bacterium, which requires cysteine for growth.[3]

Due to its low infectious dose, ease of spread by aerosol, and high virulence, F. tularensis is classified as a Tier 1 Select Agent by the U.S. government, along with other potential agents of bioterrorism such as Yersinia pestis, Bacillus anthracis, and Ebola virus. When found in nature, Francisella tularensis can survive for several weeks at low temperatures in animal carcasses, soil, and water. In the laboratory, F. tularensis appears as small rods (0.2 by 0.2 µm), and is grown best at 35–37 °C.[4]

Bacterial features

F. tularensis is a facultative intracellular bacterium that is capable of infecting most cell types, but primarily infects macrophages in the host organism. Entry into the macrophage occurs by phagocytosis and the bacterium is sequestered from the interior of the infected cell by a phagosome.[5][6]

F. tularensis then breaks out of this phagosome into the cytosol and rapidly proliferates. Eventually, the infected cell undergoes apoptosis, and the progeny bacteria are released in a single "burst" event[7] to initiate new rounds of infection.

F. tularensis colonies on an agar plate

F. tularensis colonies on an agar plate.jpg.webp) Image taken with a fluorescent microscope shows mouse macrophages 12 hours after infection with a virulent strain of Francisella tularensis (green)

Image taken with a fluorescent microscope shows mouse macrophages 12 hours after infection with a virulent strain of Francisella tularensis (green) Chocolate agar medium with Francisella tularensis

Chocolate agar medium with Francisella tularensis

Taxonomy

In terms of taxonomy we find that Francisella is the sole genus within the family Francisellaceae. Furthermore, two species within the Francisella genus exist, they are tularensis and philomiragia[8]

Sub species

Three subspecies (biovars) of F. tularensis are recognised (as of 2020):[9]

- F. t. tularensis (or type A), found predominantly in North America, is the most virulent of the four known subspecies, and is associated with lethal pulmonary infections. This includes the primary type A laboratory strain, SCHUS4.

- F. t. holarctica (also known as biovar F. t. palearctica or type B) is found predominantly in Europe and Asia, but rarely leads to fatal disease. An attenuated live vaccine strain of subspecies F. t. holarctica has been described, though it is not yet fully licensed by the Food and Drug Administration as a vaccine. This subspecies lacks the citrulline ureidase activity and ability to produce acid from glucose of biovar F. t. palearctica.

- F. t. mediasiatica, is found primarily in central Asia; little is currently known about this subspecies or its ability to infect humans.

Additionally, F. novicida has sometimes previously been classified as F. t. novicida. It was characterized as a relatively nonvirulent Francisella; only two tularemia cases in North America have been attributed to the organism, and these were only in severely immunocompromised individuals.[10][11]

Mechanism

Like many other bacteria, F. tularensis undergoes asexual replication. Bacteria divide into two daughter cells, each of which contains identical genetic information. Genetic variation may be introduced by mutation or horizontal gene transfer.[12][13]

The genome of F. t. tularensis strain SCHU4 has been sequenced.[12] The studies resulting from the sequencing suggest a number of gene-coding regions in the F. tularensis genome are disrupted by mutations, thus create blocks in a number of metabolic and synthetic pathways required for survival. This indicates F. tularensis has evolved to depend on the host organism for certain nutrients and other processes ordinarily taken care of by these disrupted genes.The F. tularensis genome contains unusual transposon-like elements resembling counterparts that normally are found in eukaryotic organisms.[12][13][14]

Phylogenetics

Much of the known global genetic diversity of F. t. holarctica is present in Sweden. This suggests this subspecies originated in Scandinavia and spread from there to the rest of Eurosiberia.[15]

Host and transmission

F. tularensis has been reported in invertebrates including insects and ticks, and vertebrates such as birds, amphibians, reptiles, fish and mammals, including humans. Human infection is often caused by vectors, particularly ticks but also mosquitos, deer flies and horse-flies. Direct contact with infected animals or carcasses is another source. Important reservoir hosts include lagomorphs , rodents,galliform birds and deer. Human-to-human transmission has,as yet, not been demonstrated.[9][16][17]

F. tularensis can survive for weeks outside a mammalian host and has been found in water, grassland, and haystacks. Aerosols containing the bacteria may be generated by disturbing carcasses due to brush cutting. Epidemiological studies have shown a positive correlation between occupations involving the above activities and infection with F. tularensis.Human infection with F. tularensis can occur by several routes; portals of entry are through blood and the respiratory system. The most common occurs via skin contact, yielding an ulceroglandular form of the disease. Inhalation of bacteria, particularly biovar F. t. tularensis, leads to the potentially lethal pneumonic tularemia.While the pulmonary and ulceroglandular forms of tularemia are more common, other routes of inoculation have been described and include oropharyngeal infection due to consumption of contaminated food or water, and conjunctival infection due to inoculation at the eye.[9][18] [19]

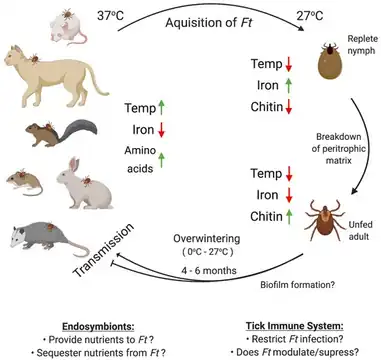

(Possible) factors affecting F. tularensis infection, persistence, and transmission in ticks[20]

(Possible) factors affecting F. tularensis infection, persistence, and transmission in ticks[20].jpg.webp) Dermacentor variabilis can transmit pathogens that cause tickborne diseases such as tularemia

Dermacentor variabilis can transmit pathogens that cause tickborne diseases such as tularemia

Virulence factors

The virulence mechanisms for F. tularensis have not been well characterized. Like other intracellular bacteria that break out of phagosomal compartments to replicate in the cytosol, F. tularensis strains produce different hemolytic agents, which may facilitate degradation of the phagosome.[21] A hemolysin activity, named NlyA, with immunological reactivity to Escherichia coli anti-HlyA antibody, was identified in biovar F. t. novicida. Acid phosphatase AcpA has been found in other bacteria to act as a hemolysin, whereas in Francisella, its role as a virulence factor is under vigorous debate.[22][23][24]

F. tularensis contains type VI secretion system (T6SS), also present in some other pathogenic bacteria.[25] It also contains a number of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins that may be linked to the secretion of virulence factors.[26] F. tularensis uses type IV pili to bind to the exterior of a host cell and thus become phagocytosed. Mutant strains lacking pili show severely attenuated pathogenicity.The expression of a protein known as IglC is required for F. tularensis phagosomal breakout and intracellular replication; in its absence, mutant F. tularensis cells die and are degraded by the macrophage. This protein is located in a putative pathogenicity island regulated by the transcription factor MglA.[22][23][27][28]

F. tularensis, downregulates the immune response of infected cells, a tactic used by a significant number of pathogenic organisms to ensure their replication is unhindered by the host immune system by blocking the warning signals from the infected cells. This downmodulation of the immune response requires the IglC protein, though again the contributions of IglC and other genes are unclear. Several other putative virulence genes exist, but have yet to be characterized for function in F. tularensis pathogenicity.[29][27]

Disease

Signs and symptoms

The incubation period for tularemia is one to 14 days; most human infections become apparent after three to five days.[30] In most susceptible mammals, the clinical signs include fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, signs of sepsis, and possibly death. Nonhuman mammals rarely develop the skin lesions seen in people. Subclinical infections are common, and animals often develop specific antibodies to the organism. Fever is moderate or very high, and tularemia bacilli can be isolated from blood cultures at this stage. The face and eyes redden and become inflamed. Inflammation spreads to the lymph nodes, which enlarge and may suppurate .[31][16][32][17]

Diagnosis

Infection by F. tularensis is diagnosed by clinicians based on symptoms and patient history, imaging, and laboratory studies.[31][6]

Prevention

Preventive measures include preventing bites from ticks, flies, and mosquitos; ensuring that all game is cooked thoroughly; refraining from drinking untreated water and using insect repellents. If working with cultures of F. tularensis, in the lab, wear a gown, impermeable gloves, mask, and eye protection. When dressing game, wear impermeable gloves. A live attenuated vaccine is available for individuals who are at high risk for exposure such, as laboratory personnel.[33]Vaccine research has been ongoing[34]

Treatment

Tularemia is treated with antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, or fluoroquinolones. About 15 proteins were suggested that could facilitate drug and vaccine design pipeline.[35]

History

This species was discovered in ground squirrels in Tulare County, California in 1911. Bacterium tularense was soon isolated by George Walter McCoy (1876–1952) of the US Plague Lab in San Francisco and reported in 1912. In 1922, Edward Francis (1872–1957), a physician and medical researcher from Ohio, discovered that Bacterium tularense was the causative agent of tularemia, after studying several cases with symptoms of the disease. Later, it became known as Francisella tularensis, in honor of the discovery by Francis.[36][37][38]

The disease was also described in the Fukushima region of Japan by Hachiro Ohara in the 1920s, where it was associated with hunting rabbits.[9]

The long history of Francisella tularensis goes back to 1653 in Norway and a description of a tularemia-like disease of lemmings, then we find in 1818 a mention of hare disease in Japan and finally, Norway again in 1890 has the medical literature refer to a lemming fever.[39]

Use as biological weapon

When the U.S. biological warfare program ended in 1969, F. tularensis was one of seven standardized biological weapons it had developed as part of German-American cooperation in the 1920s–1930s.[40]

See also

- Francisella small RNA

References

- ↑ "Francisella tularensis" (PDF). health.ny.gov. Wadsworth Center: New York State Department of Health. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ "Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)" (PDF). michigan.gov. Michigan Department of Community Health. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 488–90. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ "Francisella tularensis". Microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- ↑ Titball, Richard W.; Oyston, Petra C. F. (1 January 2009). "Chapter 61 - Francisella tularensis". Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Academic Press. pp. 1241–1253. ISBN 978-0-12-369408-9.

- 1 2 Maurin, Max (2020). "Francisella tularensis, Tularemia and Serological Diagnosis". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10: 512090. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.512090. ISSN 2235-2988. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ Carruthers, Jonathan; Lythe, Grant; López-García, Martín; Gillard, Joseph; Laws, Thomas R.; Lukaszewski, Roman; Molina-París, Carmen (2020-06-01). "Stochastic dynamics of Francisella tularensis infection and replication". PLOS Computational Biology. 16 (6): e1007752. Bibcode:2020PLSCB..16E7752C. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007752. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 7304631. PMID 32479491.

- ↑ McLendon, Molly K.; Apicella, Michael A.; Allen, Lee-Ann H. (2006). "Francisella tularensis: Taxonomy, Genetics, and Immunopathogenesis of a Potential Agent of Biowarfare". Annual review of microbiology. 60: 167–185. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142126. ISSN 0066-4227. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Sam R. Telford III, Heidi K. Goethert (2020). "Ecology of Francisella tularensis", Annual Review of Entomology 65: 351–372 doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025134

- ↑ "Francisella_tularensis". www.bionity.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ Sjöstedt AB. "Genus I. Francisella Dorofe'ev 1947, 176AL". Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 2 (The Proteobacteria), part B (The Gammaproteobacteria) (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 200–210.

- 1 2 3 Larsson P, Oyston P, Chain P, et al. (2005). "The complete genome sequence of Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia". Nat Genet. 37 (2): 153–9. doi:10.1038/ng1499. PMID 15640799.

- 1 2 Barker, Jeffrey R.; Klose, Karl E. (June 2007). "Molecular and Genetic Basis of Pathogenesis in Francisella Tularensis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1105 (1): 138–159. doi:10.1196/annals.1409.010. ISSN 0077-8923. Archived from the original on 2023-10-20. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Sjöstedt, Anders (1 February 2006). "Intracellular survival mechanisms of Francisella tularensis, a stealth pathogen". Microbes and Infection. 8 (2): 561–567. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.08.001. ISSN 1286-4579. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ↑ Karlsson E, Svensson K, Lindgren P, Byström M, Sjödin A, Forsman M, Johansson A (2012) The phylogeographic pattern of Francisella tularensis in Sweden indicates a Scandinavian origin of Eurosiberian tularaemia. Environ Microbiol doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12052

- 1 2 Snowden, Jessica; Simonsen, Kari A. (2023). "Tularemia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- 1 2 "Tularemia in Animals - Generalized Conditions". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ↑ Celli, Jean; Zahrt, Thomas C. (1 April 2013). "Mechanisms of Francisella tularensis intracellular pathogenesis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 3 (4): a010314. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a010314. ISSN 2157-1422. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Transmission of tularemia | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ↑ Tully, Brenden G.; Huntley, Jason F. (November 2020). "Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission of Francisella tularensis in Ticks". Microorganisms. 8 (11): 1639. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8111639. ISSN 2076-2607. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ↑ Mohapatra, Nrusingh P.; Soni, Shilpa; Reilly, Thomas J.; Liu, Jirong; Klose, Karl E.; Gunn, John S. (2008). "Combined Deletion of Four Francisella novicida Acid Phosphatases Attenuates Virulence and Macrophage Vacuolar Escape". Infection and Immunity. 76 (8): 3690–3699. doi:10.1128/IAI.00262-08. PMC 2493204. PMID 18490464. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-07. Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- 1 2 Jones, Bradley; Faron, Matt; Rasmussen, Jed; Fletcher, Josh (2014). "Uncovering the components of the Francisella tularensis virulence stealth strategy". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 4. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2014.00032/full. ISSN 2235-2988. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- 1 2 Hood, A. M. (August 1977). "Virulence factors of Francisella tularensis". Epidemiology & Infection. 79 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1017/S0022172400052840. ISSN 0022-1724. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ↑ "Tularemia" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ↑ Spidlova, Petra; Stulik, Jiri (2017). "Francisella tularensis type VI secretion system comes of age". Virulence. 8 (6): 628–631. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1278336. ISSN 2150-5594. PMC 5626347. PMID 28060573.

- ↑ Atkins H, Dassa E, Walker N, Griffin K, Harland D, Taylor R, Duffield M, Titball R (2006). "The identification and evaluation of ATP binding cassette systems in the intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis". Res Microbiol. 157 (6): 593–604. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2005.12.004. PMID 16503121.

- 1 2 Santic, Marina; Molmeret, Maelle; Klose, Karl E.; Jones, Snake; Kwaik, Yousef Abu (July 2005). "The Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island protein IglC and its regulator MglA are essential for modulating phagosome biogenesis and subsequent bacterial escape into the cytoplasm". Cellular Microbiology. 7 (7): 969–979. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00526.x. ISSN 1462-5814. Archived from the original on 2022-10-15. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ↑ Craig, Lisa; Forest, Katrina T.; Maier, Berenike (July 2019). "Type IV pili: dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 17 (7): 429–440. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0195-4. ISSN 1740-1534. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ↑ Bosio, Catharine (2011). "The Subversion of the Immune System by Francisella Tularensis". Frontiers in Microbiology. 2. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2011.00009/full. ISSN 1664-302X. Archived from the original on 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ Office international des épizooties. (2000). Manual of standards for diagnostic tests and vaccines: lists A and B diseases of mammals, birds and bees. Paris, France: Office international des épizooties. pp. 494–6, 1394. ISBN 978-92-9044-510-4.

- 1 2 Snowden, Jessica (2023). Tularemia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Tularemia - Infectious Diseases". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ↑ "Part IV : Acute Communicable Diseases" (PDF). Publichealth.lacounty.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ Bachert, Beth A.; Richardson, Joshua B.; Mlynek, Kevin D.; Klimko, Christopher P.; Toothman, Ronald G.; Fetterer, David P.; Luquette, Andrea E.; Chase, Kitty; Storrs, Jessica L.; Rogers, Ashley K.; Cote, Christopher K.; Rozak, David A.; Bozue, Joel A. (11 August 2021). "Development, Phenotypic Characterization and Genomic Analysis of a Francisella tularensis Panel for Tularemia Vaccine Testing". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 725776. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.725776. ISSN 1664-302X. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ Francisella tularensis: In silico Identification of Drug and Vaccine Targets by Metabolic Pathway Analysis J Harati, J Fallah The 6th Conference on Bioinformatics

- ↑ Tärnvik, A.; Berglund, L. (1 February 2003). "Tularaemia". European Respiratory Journal. 21 (2): 361–373. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00088903. PMID 12608453. S2CID 219200617. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ McCoy GW, Chapin CW. Bacterium tularense, the cause of a plaguelike disease of rodents. Public Health Bull 1912;53:17–23.

- ↑ "Jeanette Barry, Notable Contributions to Medical Research by Public Health Service Scientists. National Institute of Health, Public Health Service Publication No. 752, 1960, p. 36" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- ↑ Sjöstedt, Anders (June 2007). "Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1105: 1–29. doi:10.1196/annals.1409.009. ISSN 0077-8923. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ Croddy, Eric C. and Hart, C. Perez-Armendariz J., Chemical and Biological Warfare, (Google Books Archived 2023-04-03 at the Wayback Machine), Springer, 2002, pp. 30–31, (ISBN 0387950761), accessed October 24, 2008.

External links

- Francisella Genome Projects Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (from Genomes OnLine Database Archived 2011-10-15 at the Wayback Machine)

- Comparative Analysis of Francisella Genomes (at DOE's IMG system)

- Francisella tularensis information from the CDC/National Center for Infectious Diesase:

- BioHealthBase Bioinformatics Resource Center Archived 2019-02-07 at the Wayback Machine The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) supports a public database describing the molecular genetics of F. tularensis. The website describes the genes, proteins, and cellular characteristics of the pathogen.

- Type strain of Francisella tularensis at BacDive – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Archived 2022-12-01 at the Wayback Machine