Yersinia enterocolitica

| Yersinia enterocolitica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacterales |

| Family: | Yersiniaceae |

| Genus: | Yersinia |

| Species: | Y. enterocolitica |

| Binomial name | |

| Yersinia enterocolitica (Schleifstein & Coleman 1939) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

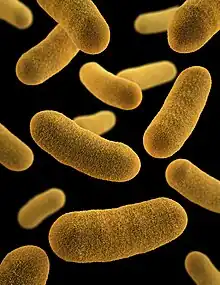

Yersinia enterocolitica is a Gram-negative, bacillus-shaped bacterium, belonging to the family Yersiniaceae. It is motile at temperatures of 22–29°C (72–84°F), but becomes nonmotile at normal human body temperature.[1][2] Y. enterocolitica infection causes the disease yersiniosis, which is an animal-borne disease occurring in humans, as well as in a wide array of animals such as cattle, deer, pigs, and birds. Many of these animals recover from the disease and become carriers; these are potential sources of contagion despite showing no signs of disease.[3] The bacterium infects the host by sticking to its cells using trimeric autotransporter adhesins.

Y. enterocolitica is a heterogeneous group of strains, which are traditionally classified by biotyping into six biogroups on the basis of phenotypic characteristics, and by serotyping into more than 57 O serogroups, on the basis of their O (lipopolysaccharide or LPS) surface antigen. Five of the six biogroups (1B and 2–5) are regarded as pathogens. However, only a few of these serogroups have been associated with disease in either humans or animals. Strains that belong to serogroups O:3 (biogroup 4), O:5,27 (biogroups 2 and 3), O:8 (biogroup 1B), and O:9 (biogroup 2) are most frequently isolated worldwide from human samples. However, the most important Y. enterocolitica serogroup in many European countries is serogroup O:3 followed by O:9, whereas the serogroup O:8 is mainly detected in the United States.

Y. enterocolitica is widespread in nature, occurring in reservoirs ranging from the intestinal tracts of numerous mammals, avian species, cold-blooded species, and even from terrestrial and aquatic niches. Most environmental isolates are avirulent; however, isolates recovered from porcine sources contain human pathogenic serogroups. In addition, dogs, sheep, wild rodents, and environmental water may also be a reservoir of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains. Human pathogenic strains are usually confined to the intestinal tract and lead to enteritis/diarrhea.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Yersinia includes 20 species: Y. aldovae, Y. aleksiciae, Y. bercovieri, Y. canariae, Y. enterocolitica, Y. entomophaga, Y. frederiksenii, Y. hibernica, Y. intermedia, Y. kristensenii, Y. massiliensis, Y. mollaretii, Y. nurmii, Y. pekkanenii, Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. rohdei, Y. ruckeri, Y. similis, and Y. wautersii. Among them, only Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and certain strains of Y. enterocolitica are of pathogenic importance for humans and certain warm-blooded animals, whereas the other species are of environmental origin and may, at best, act as opportunists. However, Yersinia strains can be isolated from clinical materials, so they have to be identified at the species level.

Infection

Signs and symptoms

The portal of entry is the gastrointestinal tract. The organism is acquired usually by insufficiently cooked pork or contaminated water, meat, or milk. In recent years Y. enterocolitica has increasingly been causing smaller outbreaks via ready-to-eat (RTE) vegetables.[5] Acute Y. enterocolitica infections usually lead to mild, self-limiting enterocolitis or terminal ileitis and adenitis in humans. Yersiniosis symptoms may include watery or bloody diarrhea and fever, resembling appendicitis, salmonellosis, or shigellosis. After oral uptake, Yersinia species replicate in the terminal ileum and invade Peyer's patches. From here, they can disseminate further to mesenteric lymph nodes causing lymphadenopathy. This condition can be confused with appendicitis, so is called pseudoappendicitis. In immunosuppressed individuals, they can disseminate from the gut to the liver and spleen and form abscesses.

Risk factors

.jpg.webp)

Because Yersinia species are siderophilic (iron-loving) bacteria, people with hereditary hemochromatosis (a disease resulting in high body iron levels) are more susceptible to infection with Yersinia (and other siderophilic bacteria). In fact, the most common contaminant of stored blood is Y. enterocolitica.[6]

Treatment

Yersiniosis is usually self-limiting and does not require treatment. For sepsis or severe focal infections, especially if associated with immunosuppression, the recommended regimen includes doxycycline in combination with an aminoglycoside. Other antibiotics active against Y. enterocolitica include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxasole, fluoroquinolones, ceftriaxone, and chloramphenicol. Y. enterocolitica is usually resistant to penicillin G, ampicillin, and cefalotin due to beta-lactamase production, but multidrug resistant strains have been reported in Europe.[5][7][8]

Prognosis

Y. enterocolitica infections are sometimes followed by chronic inflammatory diseases such as arthritis,[9] erythema nodosum, and reactive arthritis. This is most likely because of some immune-mediated mechanism.[10]

Y. enterocolitica seems to be associated with autoimmune Graves-Basedow thyroiditis.[11] Whilst indirect evidence exists, direct causative evidence is limited.[12] Y. enterocolitica is probably not a major cause of this disease, but may contribute to the development of thyroid autoimmunity arising for other reasons in genetically susceptible individuals.[13] Y. enterocolitica infection has also been suggested to be not the cause of autoimmune thyroid disease, but rather an associated condition, with both sharing a common inherited susceptibility.[14] More recently, the role for Y. enterocolitica has been disputed.[15]

References

- ↑ Kapatral, V.; Olson, J. W.; Pepe, J. C.; Miller, V. L.; Minnich, S. A. (1996-03-01). "Temperature-dependent regulation of Yersinia enterocolitica Class III flagellar genes". Molecular Microbiology. 19 (5): 1061–1071. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.452978.x. ISSN 0950-382X. PMID 8830263. S2CID 33161333.

- ↑ "Yersinia spp. | MicrobLog: Microbiology Training Log". microblog.me.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ↑ Collins FM (1996). "Pasteurella, and Francisella". In Barron S; et al. (eds.). Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. NBK7798. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ↑ Fàbrega A, Vila J (2012). "Yersinia enterocolitica: pathogenesis, virulence and antimicrobial resistance". Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica. 30 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2011.07.017. PMID 22019131.

- 1 2 Karlsson, Philip A.; Tano, Eva; Jernberg, Cecilia; Hickman, Rachel A.; Guy, Lionel; Järhult, Josef D.; Wang, Helen (2021-05-13). "Molecular Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Yersinia enterocolitica From Foodborne Outbreaks in Sweden". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 664665. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.664665. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 8155512. PMID 34054769.

- ↑ Goljan, Edward F. Rapid Review Pathology. Second Edition. Page 279, Table 15-1.

- ↑ Karlsson, Philip A.; Hechard, Tifaine; Jernberg, Cecilia; Wang, Helen (2021-05-13). Rasko, David (ed.). "Complete Genome Assembly of Multidrug-Resistant Yersinia enterocolitica Y72, Isolated in Sweden". Microbiology Resource Announcements. 10 (19): e00264-21. doi:10.1128/MRA.00264-21. ISSN 2576-098X. PMC 8142573. PMID 33986087.

- ↑ Bottone, Edward (April 1997). "Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 10 (2): 257–276. doi:10.1128/CMR.10.2.257. PMC 172919. PMID 9105754.

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS (2003). "Arthritis associated with enteric infection". Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 17 (2): 219–39. doi:10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00104-3. PMID 12787523.

- ↑ Benvenga S, Santarpia L, Trimarchi F, Guarneri F (2006). "Human Thyroid Autoantigens and Proteins of Yersinia and Borrelia Share Amino Acid Sequence Homology That Includes Binding Motifs to HLA-DR Molecules and T-Cell Receptor". Thyroid. 16 (3): 225–236. doi:10.1089/thy.2006.16.225. PMID 16571084.

- ↑ Tomer Y, Davies T (1993). "Infection, thyroid disease, and autoimmunity" (PDF). Endocrine Reviews. 14 (1): 107–20. doi:10.1210/edrv-14-1-107. PMID 8491150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-23. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ↑ Toivanen P, Toivanen A (1994). "Does Yersinia induce autoimmunity?". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 104 (2): 107–11. doi:10.1159/000236717. PMID 8199453.

- ↑ Strieder T, Wenzel B, Prummel M, Tijssen J, Wiersinga W (2003). "Increased prevalence of antibodies to enteropathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica virulence proteins in relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease". Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 132 (2): 278–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02139.x. PMC 1808711. PMID 12699417.

- ↑ Hansen P, Wenzel B, Brix T, Hegedüs L (2006). "Yersinia enterocolitica infection does not confer an increased risk of thyroid antibodies: evidence from a Danish twin study". Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 146 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03183.x. PMC 1809723. PMID 16968395.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Yersinia enterocolitica |

- Yersinia enterocolitica Archived 2011-08-24 at the Wayback Machine genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- Yersinia enterocolitica Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine in the NCBI Taxonomy Browser

- Type strain of Yersinia enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica Archived 2020-09-26 at the Wayback Machine at BacDive – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase