Vienna

Vienna (/viˈɛnə/ ⓘ vee-EN-ə;[7][8] German: Wien [viːn] ⓘ; Austro-Bavarian: Wean [veɐ̯n]) is the capital, largest city, and one of nine States of Austria. Vienna is Austria's most populous city and its primate city, with about two million inhabitants[9] (2.9 million within the metropolitan area,[10] nearly one-third of the country's population), and its cultural, economic, and political center. It is the sixth-largest city proper by population in the European Union and the largest of all cities on the Danube river.

Vienna

| |

|---|---|

Capital city, state and municipality | |

Flag  Seal | |

Vienna Location within Austria  Vienna Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 48°12′30″N 16°22′21″E | |

| Country | Austria |

| Province | Vienna |

| Government | |

| • Body | State and Municipality Diet |

| • Mayor and Governor | Michael Ludwig (SPÖ) |

| Area | |

| • Capital city, state and municipality | 414.78 km2 (160.15 sq mi) |

| • Land | 395.25 km2 (152.61 sq mi) |

| • Water | 19.39 km2 (7.49 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 151 (Lobau) – 542 (Hermannskogel) m (495–1,778 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Rank | 1st in Austria (5th in EU) |

| • Density | 4,326.1/km2 (11,205/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,951,354 |

| • Metro | 2,890,577 |

| • Ethnicity[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | German: Wiener (m), Wienerin (f) Viennese |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code |

|

| ISO 3166 code | AT-9 |

| Vehicle registration | W |

| HDI (2019) | 0.947[4] very high · 1st of 9 |

| Gross Regional Product | € 102 billion (2021)[5] |

| Seats in the Federal Council | 11 / 61

|

| GeoTLD | .wien |

| Website | wien |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Vienna |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 2001 (25th session) |

| Reference no. | 1033 |

| UNESCO Region | Europe and North America |

| Endangered | 2017–present[6] |

Until the beginning of the 20th century, Vienna was the largest German-speaking city in the world, and before the splitting of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I, the city had two million inhabitants.[11] Today, it is the second-largest German-speaking city after Berlin.[12][13] Vienna is host to many major international organizations, including the United Nations, OPEC and the OSCE. The city is located in the eastern part of Austria and is close to the borders of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. These regions work together in a European Centrope border region. Along with nearby Bratislava, Vienna forms a metropolitan region with 3 million inhabitants. In 2001, the city center was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In July 2017 it was moved to the list of World Heritage in Danger.[14]

Additionally, Vienna has been called the "City of Music"[15] due to its musical legacy, as many famous classical musicians such as Beethoven and Mozart called Vienna home. Vienna is also said to be the "City of Dreams" because it was home to the world's first psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud.[16] Vienna's ancestral roots lie in early Celtic and Roman settlements that transformed into a Medieval and Baroque city. It is well known for having played a pivotal role as a leading European music center, from the age of Viennese Classicism through the early part of the 20th century. The historic center of Vienna is rich in architectural ensembles, including Baroque palaces and gardens, and the late-19th-century Ringstraße lined with grand buildings, monuments and parks.[17]

Etymology

The English name Vienna is borrowed from the homonymous Italian name. The etymology of the city's name is still subject to scholarly dispute. Some claim that the name comes from vedunia, meaning "forest stream", which subsequently produced the Old High German uuenia (wenia in modern writing), the New High German wien and its dialectal variant wean.[18][19][20]

Others believe that the name comes from the Roman settlement name of Celtic extraction Vindobona, probably meaning "fair village, white settlement" from Celtic roots, vindo-, meaning "bright" or "fair" (as in the Irish fionn and the Welsh gwyn), and -bona "village, settlement".[21] The Celtic word vindos may reflect a widespread prehistorical cult of Vindos, a Celtic deity who survives in Irish mythology as the warrior and seer Fionn mac Cumhaill.[22][23] A variant of this Celtic name could be preserved in the Czech, Slovak, Polish and Ukrainian names of the city (Vídeň, Viedeň, Wiedeń and Відень respectively) and in that of the city's district Wieden.[24]

Another theory suggests the name comes from the Wends (Old English: Winedas; Old Norse: Vindr; German: Wenden, Winden; Dutch: Wenden; Danish: vendere; Swedish: vender; Polish: Wendowie; Czech: Vendové) which is a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas.

The name of the city in Hungarian (Bécs), Serbo-Croatian (Beč, Беч) and Ottoman Turkish (Turkish: Beç) has a different, probably Slavonic origin, and originally referred to an Avar fort in the area.[25] Slovene speakers call the city Dunaj, which in other Central European Slavic languages means the river Danube, on which the city stands.

History

Early history

Evidence has been found of continuous habitation in the Vienna area since 500 BC, when Celts settled the site on the Danube.[26] In 15 BC, the Romans fortified the frontier city they called Vindobona to guard the empire against Germanic tribes to the north.

Close ties with other Celtic peoples continued through the ages. The Irish monk Saint Colman (or Koloman, Irish Colmán, derived from colm "dove") is buried in Melk Abbey and Saint Fergil (Virgil the Geometer) served as Bishop of Salzburg for forty years. Irish Benedictines founded twelfth-century monastic settlements; evidence of these ties persists in the form of Vienna's great Schottenstift monastery (Scots Abbey), once home to many Irish monks.

In 976, Leopold I of Babenberg became count of the Eastern March, a district centered on the Danube on the eastern frontier of Bavaria. This initial district grew into the duchy of Austria. Each succeeding Babenberg ruler expanded the march east along the Danube, eventually encompassing Vienna and the lands immediately east. In 1145, Henry II, Duke of Austria moved the Babenberg family residence from Klosterneuburg in Lower Austria to Vienna. From that time, Vienna remained the center of the Babenberg dynasty.[27]

In 1440, Vienna became the resident city of the Habsburg dynasty. It eventually grew to become the de facto capital of the Holy Roman Empire (800–1806) in 1437 and a cultural center for arts and science, music and fine cuisine. Hungary occupied the city between 1485 and 1490.

-Allen.jpg.webp)

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Christian forces twice stopped Ottoman armies outside Vienna, in the 1529 siege of Vienna and the 1683 Battle of Vienna. The Great Plague of Vienna ravaged the city in 1679, killing nearly a third of its population.[28]

Austrian Empire and the early 20th century

In 1804, during the Napoleonic Wars, Vienna became the capital of the newly formed Austrian Empire. The city continued to play a major role in European and world politics, including hosting the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15. The city also saw major uprisings against Habsburg rule in 1848, which were suppressed. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Vienna remained the capital of what became the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The city functioned as a center of classical music, for which the title of the First Viennese School (Haydn/Mozart/Beethoven/Schubert) is sometimes applied.

During the latter half of the 19th century, Vienna developed what had previously been the bastions and glacis into the Ringstraße, a new boulevard surrounding the historical town and a major prestige project. Former suburbs were incorporated, and the city of Vienna grew dramatically. In 1918, after World War I, Vienna became capital of the Republic of German-Austria, and then in 1919 of the First Republic of Austria.

From the late-19th century to 1938, the city remained a center of high culture and of modernism. A world capital of music, Vienna played host to composers such as Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler and Richard Strauss. The city's cultural contributions in the first half of the 20th century included, among many, the Vienna Secession movement in art, the Second Viennese School, the architecture of Adolf Loos, the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the Vienna Circle.

Red Vienna

_-_Karl-Marx-Hof.JPG.webp)

The city of Vienna became the center of socialist politics from 1919 to 1934, a period sometimes referred to as "Red Vienna" (Das rote Wien). After a new breed of socialist politicians won the local elections they engaged in a brief but ambitious municipal experiment.[29] Social democrats had won an absolute majority in the May 1919 municipal election and ruled the city council with 100 of the 165 seats. Jakob Reumann was appointed by the city council as city mayor.[30] The theoretical foundations of so called Austromarxism were established by Otto Bauer, Karl Renner, and Max Adler.[31]

In the Austrian Civil War of 1934 Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss sent the Austrian Armed Forces to shell civilian housing such as the Karl Marx-Hof occupied by the Republikanischer Schutzbund (socialist militia).

Anschluss and World War II

In 1938, after a triumphant entry into Austria, the Austrian-born German Chancellor Adolf Hitler spoke to the Austrian Germans from the balcony of the Neue Burg, a part of the Hofburg at the Heldenplatz. In the ensuing days the new Nazi authorities oversaw the harassment of Viennese Jews, the looting of their homes, and their on-going deportation and murder.[32][33] Between 1938 (after the Anschluss) and the end of the Second World War in 1945, Vienna lost its status as a capital to Berlin, because Austria ceased to exist and became part of Nazi Germany.

During the November pogroms on 9 November 1938, 92 synagogs in Vienna were destroyed. Only the city temple in the 1st district was spared, as the data of all Jews in Vienna were collected in the adjacent archives. Adolf Eichmann held office in the expropriated Palais Rothschild and organized the expropriation and persecution of the Jews. Of the almost 200,000 Jews in Vienna, around 120,000 were driven to emigrate and around 65,000 were killed. After the end of the war, the Jewish population of Vienna was only about 5,000.[34][35][36][37]

Vienna was also the center of the important resistance group around Heinrich Maier, which provided the Allies with plans for V-1, V-2 rockets, Peenemünde, Tiger tanks, Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet and other aircraft. The information was important to Operation Crossbow and Operation Hydra, both preliminary missions for Operation Overlord. In addition, factory locations for war-essential products were communicated as targets for the Allied Air Force. The group was exposed and most of its members were executed after months of torture by the Gestapo in Vienna.[38][39][40][41] The group around the later executed Karl Burian even tried to blow up the Gestapo headquarters in the Hotel Metropole.[42]

On 2 April 1945, the Soviet Red Army launched the Vienna Offensive against the Germans holding the city and besieged it. British and American air-raids, as well as artillery duels between the Red Army and the SS and Wehrmacht, crippled infrastructure, such as tram services and water- and power-distribution, and destroyed or damaged thousands of public and private buildings. The Red Army was helped by an Austrian resistance group in the German Wehrmacht. The group tried under the code name Radetzky to prevent the destruction and fighting in the city. Vienna fell eleven days later.[43] At the end of the war, Austria again became separated from Germany, and Vienna regained its status as the capital city of the Republic of Austria, but the Soviet hold on the city remained until 1955,[44][45] when Austria regained full sovereignty.

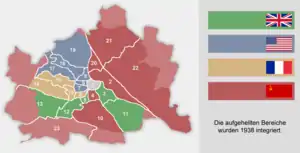

Four-power Vienna

After the war, Vienna was part of Soviet-occupied Eastern Austria until September 1945. As in Berlin, Vienna in September 1945 was divided into sectors by the four powers: the US, the UK, France, and the Soviet Union and supervised by an Allied Commission. The four-power occupation of Vienna differed in one key respect from that of Berlin: the central area of the city, known as the first district, constituted an international zone in which the four powers alternated control on a monthly basis. The control was policed by the four powers on a de facto day-to-day basis, the famous "four soldiers in a jeep" method.[46] The Berlin Blockade of 1948 raised Western concerns that the Soviets might repeat the blockade in Vienna. The matter was raised in the UK House of Commons by MP Anthony Nutting, who asked: "What plans have the Government for dealing with a similar situation in Vienna? Vienna is in exactly a similar position to Berlin."[47]

There was a lack of airfields in the Western sectors, and authorities drafted contingency plans to deal with such a blockade. Plans included the laying down of metal landing mats at Schönbrunn. The Soviets did not blockade the city. The Potsdam Agreement included written rights of land access to the western sectors, whereas no such written guarantees had covered the western sectors of Berlin. Also, there was no precipitating event to cause a blockade in Vienna. (In Berlin, the Western powers had introduced a new currency in early 1948 to economically freeze out the Soviets.) During the 10 years of the four-power occupation, Vienna became a hotbed for international espionage between the Western and Eastern blocs. In the wake of the Berlin Blockade, the Cold War in Vienna took on a different dynamic. While accepting that Germany and Berlin would be divided, the Soviets had decided against allowing the same state of affairs to arise in Austria and Vienna. Here, the Soviet forces controlled districts 2, 4, 10, 20, 21, and 22 and all areas incorporated into Vienna in 1938.

Barbed wire fences were installed around the perimeter of West Berlin in 1953, but not in Vienna. By 1955, the Soviets, by signing the Austrian State Treaty, agreed to relinquish their occupation zones in Eastern Austria as well as their sector in Vienna. In exchange they required that Austria declare its permanent neutrality after the allied powers had left the country. Thus they ensured that Austria would not be a member of NATO and that NATO forces would therefore not have direct communications between Italy and West Germany.

The atmosphere of four-power Vienna is the background for Graham Greene's screenplay for the film The Third Man (1949). Later he adapted the screenplay as a novel and published it. Occupied Vienna is also depicted in the 1991 Philip Kerr novel, A German Requiem.

Austrian State Treaty and afterwards

The four-power control of Vienna lasted until the Austrian State Treaty was signed in May 1955. That year, after years of reconstruction and restoration, the State Opera and the Burgtheater, both on the Ringstraße, reopened to the public. The Soviet Union signed the State Treaty only after having been provided with a political guarantee by the federal government to declare Austria's neutrality after the withdrawal of the allied troops. This law of neutrality, passed in late October 1955 (and not the State Treaty itself), ensured that modern Austria would align with neither NATO nor the Soviet bloc, and is considered one of the reasons for Austria's delayed entry into the European Union in 1995.

In the 1970s, Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky inaugurated the Vienna International Center, a new area of the city created to host international institutions. Vienna has regained much of its former international stature by hosting international organizations, such as the United Nations (United Nations Industrial Development Organization, United Nations Office at Vienna and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime), the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

On 3 November 2020, a series of shootings rocked Vienna. Four civilians were killed, including the attacker, who was identified as a sympathiser of the Islamic State.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1637 | 60,000 | — |

| 1683 | 90,000 | +50.0% |

| 1710 | 113,800 | +26.4% |

| 1754 | 175,460 | +54.2% |

| 1783 | 247,753 | +41.2% |

| 1793 | 271,800 | +9.7% |

| 1830 | 401,200 | +47.6% |

| 1840 | 469,400 | +17.0% |

| 1850 | 551,300 | +17.4% |

| 1857 | 683,000 | +23.9% |

| 1869 | 900,998 | +31.9% |

| 1880 | 1,162,591 | +29.0% |

| 1890 | 1,430,213 | +23.0% |

| 1900 | 1,769,137 | +23.7% |

| 1910 | 2,083,630 | +17.8% |

| 1916 | 2,239,000 | +7.5% |

| 1923 | 1,918,720 | −14.3% |

| 1934 | 1,935,881 | +0.9% |

| 1939 | 1,770,938 | −8.5% |

| 1951 | 1,616,125 | −8.7% |

| 1961 | 1,627,566 | +0.7% |

| 1971 | 1,619,885 | −0.5% |

| 1981 | 1,535,145 | −5.2% |

| 1990 | 1,492,636 | −2.8% |

| 2000 | 1,548,537 | +3.7% |

| 2005 | 1,632,569 | +5.4% |

| 2010 | 1,689,995 | +3.5% |

| 2015 | 1,797,337 | +6.4% |

| 2020 | 1,911,728 | +6.4% |

| 2020 data[48]</ref> | ||

| Country of birth | Population as of 1 January 2023 |

|---|---|

| 88,715 | |

| 65,649 | |

| 60,513 | |

| 48,741 | |

| 46,736 | |

| 39,327 | |

| 38,115 | |

| 34,285 | |

| 24,145 | |

| 22,084 | |

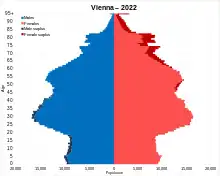

Because of the industrialization and migration from other parts of the Empire, the population of Vienna increased sharply during its time as the capital of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918). In 1910, Vienna had more than two million inhabitants, and was the third largest city in Europe after London and Paris.[50] Around the start of the 20th century, Vienna was the city with the second-largest Czech population in the world (after Prague).[51] After World War I, many Czechs and Hungarians returned to their ancestral countries, resulting in a decline in the Viennese population. After World War II, the Soviets used force to repatriate key workers of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian origins to return to their ethnic homelands to further the Soviet bloc economy. The population of Vienna generally stagnated or declined through the remainder of the 20th century, not demonstrating significant growth again until the census of 2000. In 2020, Vienna's population remained significantly below its reported peak in 1916.

Under the Nazi regime, 65,000 Jews were deported and murdered in concentration camps by Nazi forces; approximately 130,000 fled.[52]

By 2001, 16% of people living in Austria had nationalities other than Austrian, nearly half of whom were from former Yugoslavia;[53][54] the next most numerous nationalities in Vienna were Turks (39,000; 2.5%), Poles (13,600; 0.9%) and Germans (12,700; 0.8%).

As of 2012, an official report from Statistics Austria showed that more than 660,000 (38.8%) of the Viennese population have full or partial migrant background, mostly from Ex-Yugoslavia, Turkey, Germany, Poland, Romania and Hungary.[9][55]

From 2005 to 2015 the city's population grew by 10.1%.[56] According to UN-Habitat, Vienna could be the fastest growing city out of 17 European metropolitan areas until 2025 with an increase of 4.65% of its population, compared to 2010.[57]

| Population | 2021 |

|---|---|

| Native born | 966,500 |

| Population with 1st gen migration background | 663,800 |

| Population with 2nd gen migration background | 255,100 |

| Total | 1,885,400 |

Religion

According to the 2001 census, 49.2% of Viennese were Catholic, while 25.7% were of no religion, 7.8% were Muslim, 6.0% were members of an Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, 4.7% were Protestant (mostly Lutheran), 0.5% were Jewish and 6.3% were either of other religions or did not reply. A 2011 report by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis showed the proportions had changed, with 41.3% Catholic, 31.6% no affiliation, 11.6% Muslim, 8.4% Eastern Orthodox, 4.2% Protestant, and 2.9% other.[60] One sources estimates that Vienna's Jewish community is of 8,000 members meanwhile another suggest 15,000.[61][62]

Based on information provided to city officials by various religious organizations about their membership, Vienna's Statistical Yearbook 2019 reports in 2018 an estimated 610,269 Roman Catholics, or 32.3% of the population, and 195,000 (10.3%) Muslims, 70,298 (3.7%) Orthodox, 57,502 (3.0%) other Christians, and 9,504 (0.5%) other religions.[63] A study conducted by the Vienna Institute of Demography estimated the 2018 proportions to be 34% Catholic, 30% unaffiliated, 15% Muslim, 10% Orthodox, 4% Protestant, and 6% other religions.[64][65]

As of the spring of 2014, Muslims made up 30% of the total proportion of schoolchildren in Vienna.[66][67]

Vienna is the seat of the Metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna, in which is also vested the exempt Ordinariate for Byzantine-Rite Catholics in Austria; its Archbishop is Cardinal Christoph Schönborn. Many Catholic Churches in central Vienna feature performances of religious or other music, including masses sung to classical music and organ. Some of Vienna's most significant historical buildings are Catholic churches, including the St. Stephen's Cathedral (Stephansdom), Karlskirche, Peterskirche and the Votivkirche. On the banks of the Danube, there is a Buddhist Peace Pagoda, built in 1983 by the monks and nuns of Nipponzan Myohoji.

Geography

Vienna is located in northeastern Austria, at the easternmost extension of the Alps in the Vienna Basin. The earliest settlement, at the location of today's inner city, was south of the meandering Danube while the city now spans both sides of the river. Elevation ranges from 151 to 542 m (495 to 1,778 ft). The city has a total area of 414.65 square kilometers (160.1 sq mi), making it the largest city in Austria by area.

Climate

Vienna has an oceanic climate (Köppen classification Cfb), transitioning to a humid subtropical climate Cfa, in the urban core in recent decades, with summer average temperatures pushing over 22C/72F in July and August in the Innere Stadt. The city has warm summers, with periodical precipitations that can reach its yearly peak in July and August (66.6 and 66.5 mm respectively) and average high temperatures from June to September of approximately 21 to 27 °C (70 to 81 °F), with a record maximum exceeding 38 °C (100 °F) and a record low in September of 5.6 °C (42 °F). Winters are relatively dry and cold with average temperatures at about freezing point. Spring is variable and autumn cool, with possible snowfalls already in November. Precipitation is generally moderate throughout the year, averaging around 550 mm (21.7 in) annually, with considerable local variations, the Vienna Woods region in the west being the wettest part (700 to 800 mm (28 to 31 in) annually) and the flat plains in the east being the driest part (500 to 550 mm (20 to 22 in) annually). Snow in winter is common, even if not so frequent compared to the Western and Southern regions of Austria.

| Climate data for Vienna (Hohe Warte) 1991–2020, extremes 1775–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.8 (35.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.8 (−10.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.1 (1.66) |

38.1 (1.50) |

51.6 (2.03) |

41.8 (1.65) |

78.9 (3.11) |

70.0 (2.76) |

77.7 (3.06) |

69.1 (2.72) |

64.1 (2.52) |

46.9 (1.85) |

46.0 (1.81) |

46.8 (1.84) |

673.1 (26.50) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.9 (6.3) |

13.6 (5.4) |

5.2 (2.0) |

1.1 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

3.2 (1.3) |

10.8 (4.3) |

50.2 (19.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.7 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 96.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 11.4 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 6.2 | 31.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 14:00) | 73.4 | 64.9 | 57.7 | 51.6 | 54.6 | 54.4 | 53.3 | 52.8 | 58.4 | 66.2 | 74.3 | 76.6 | 61.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.2 | 104.9 | 155.1 | 216.5 | 248.3 | 260.5 | 273.6 | 266.3 | 191.7 | 129.9 | 67.7 | 57.1 | 2,041.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26.4 | 37.5 | 43.0 | 54.1 | 54.4 | 56.3 | 58.6 | 62.1 | 52.2 | 40.0 | 25.1 | 22.6 | 44.4 |

| Source 1: Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics[68] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows),[69] wien.orf.at[70] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Vienna (Innere Stadt) 1991–2020, extremes 1961–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.1 (93.4) |

37.7 (99.9) |

38.4 (101.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.5 (94.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.1 (70.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.6 (0.3) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.6 (1.48) |

33.5 (1.32) |

46.3 (1.82) |

39.6 (1.56) |

78.3 (3.08) |

82.0 (3.23) |

80.3 (3.16) |

73.8 (2.91) |

67.3 (2.65) |

47.7 (1.88) |

42.9 (1.69) |

39.9 (1.57) |

669.2 (26.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.5 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 91.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 14:00) | 75.0 | 67.6 | 62.1 | 53.9 | 54.3 | 56.9 | 54.4 | 54.4 | 61.0 | 64.9 | 74.9 | 78.4 | 63.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.4 | 103.7 | 154.9 | 216.6 | 248.5 | 259.1 | 273.3 | 266.3 | 194.0 | 133.3 | 70.7 | 57.1 | 2,047.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26.7 | 37.1 | 42.8 | 53.8 | 53.9 | 55.2 | 57.9 | 61.7 | 52.6 | 40.9 | 26.4 | 23.0 | 44.3 |

| Source: Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics[68][71] | |||||||||||||

World heritage in danger

Vienna was moved to the UNESCO world heritage in endangered list in 2017. The main reason was a planned high-rise development.[72] The city's social democratic party planned construction of a 6,500 m2 (70,000 sq ft) complex in 2019.[72] The plan includes a 66.3 m (218 ft)-high tower, which was reduced from 75 m (246 ft) due to opposition.[72] UNESCO believed that the project "fails to comply fully with previous committee decisions, notably concerning the height of new constructions, which will impact adversely the outstanding universal value of the site".[72] UNESCO set the restriction for the height of the construction in the city center to 43 m (141 ft).[72]

The citizens of Vienna also opposed the construction of the complex because they are afraid of losing UNESCO status and also of encouraging future high-rise development.[72] The city officials replied that they will convince the WHC to maintain UNESCO world heritage status and said that no further high-rise developments are being planned.[72]

UNESCO is concerned about the height of high-rise development in Vienna as it can dramatically influence the visual integrity of the city,[73] specifically the baroque palaces.[73] Visual impact studies are being done in the Vienna city center to assess the level of visual disturbance to visitors and how the changes influenced the city's visual integrity.[73]

Districts and enlargement

Vienna is composed of 23 districts (Bezirke). Administrative district offices in Vienna (called Magistratische Bezirksämter) serve functions similar to those in the other Austrian states (called Bezirkshauptmannschaften), the officers being subject to the mayor of Vienna; with the notable exception of the police, which is under federal supervision.

District residents in Vienna (Austrians as well as EU citizens with permanent residence here) elect a District Assembly (Bezirksvertretung). City hall has delegated maintenance budgets, e.g., for schools and parks, so that the districts are able to set priorities autonomously. Any decision of a district can be overridden by the city assembly (Gemeinderat) or the responsible city councilor (amtsführender Stadtrat).

The heart and historical city of Vienna, a large part of today's Innere Stadt, was a fortress surrounded by fields to defend itself from potential attackers. In 1850, Vienna with the consent of the emperor annexed 34 surrounding villages,[74] called Vorstädte, into the city limits (districts no. 2 to 8, after 1861 with the separation of Margareten from Wieden no. 2 to 9). Consequently, the walls were razed after 1857,[75] making it possible for the city center to expand.

In their place, a broad boulevard called the Ringstraße was built, along which imposing public and private buildings, monuments, and parks were created by the start of the 20th century. These buildings include the Rathaus (town hall), the Burgtheater, the University, the Parliament, the twin museums of natural history and fine art, and the Staatsoper. It is also the location of New Wing of the Hofburg, the former imperial palace, and the Imperial and Royal War Ministry finished in 1913. The mainly Gothic Stephansdom is located at the center of the city, on Stephansplatz. The Imperial-Royal Government set up the Vienna City Renovation Fund (Wiener Stadterneuerungsfonds) and sold many building lots to private investors, thereby partly financing public construction works.

From 1850 to 1890, city limits in the West and the South mainly followed another wall called Linienwall at which a road toll called the Liniengeld was charged. Outside this wall from 1873 onwards a ring road called Gürtel was built. In 1890 it was decided to integrate 33 suburbs (called Vororte) beyond that wall into Vienna by 1 January 1892[76] and transform them into districts no. 11 to 19 (district no. 10 had been constituted in 1874); hence the Linienwall was torn down beginning in 1894.[77] In 1900, district no. 20, Brigittenau, was created by separating the area from the 2nd district.

From 1850 to 1904, Vienna had expanded only on the right bank of the Danube, following the main branch before the regulation of 1868–1875, i.e., the Old Danube of today. In 1904, the 21st district was created by integrating Floridsdorf, Kagran, Stadlau, Hirschstetten, Aspern and other villages on the left bank of the Danube into Vienna, in 1910 Strebersdorf followed. On 15 October 1938 the Nazis created Great Vienna with 26 districts by merging 97 towns and villages into Vienna, 80 of which were returned to surrounding Lower Austria in 1954.[76] Since then Vienna has had 23 districts.

Industries are located mostly in the southern and eastern districts. The Innere Stadt is situated away from the main flow of the Danube, but is bounded by the Donaukanal ("Danube canal"). Vienna's second and twentieth districts are located between the Donaukanal and the Danube. Across the Danube, where the Vienna International Center is located (districts 21–22), and in the southern areas (district 23) are the newest parts of the city.

Politics

Political history

In the twenty years before the First World War and until 1918, Viennese politics were shaped by the Christian Social Party. In particular, long-term mayor Karl Lueger was able to not apply the general voting rights for men introduced by and for the parliament of imperial Austria, the Reichsrat, in 1907, thereby excluding most of the working class from taking part in decisions. For Adolf Hitler, who spent some years in Vienna, Lueger was a teacher of how to use antisemitism in politics.

Vienna is today considered the center of the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ). During the period of the First Republic (1918–1934), the Vienna Social Democrats undertook many social reforms. At that time, Vienna's municipal policy was admired by Socialists throughout Europe, who therefore referred to the city as "Red Vienna" (Rotes Wien). In February 1934 troops of the Austrian federal government under Engelbert Dollfuss, who had closed down the first chamber of the federal parliament, the Nationalrat, in 1933, and paramilitary socialist organizations were engaged in the Austrian Civil War, which led to the ban of the Social Democratic party.

The SPÖ has held the mayor's office and control of the city council/parliament at every free election since 1919. The only break in this SPÖ dominance came between 1934 and 1945, when the Social Democratic Party was illegal, mayors were appointed by the austro-fascist and later by the Nazi authorities. The mayor of Vienna is Michael Ludwig of the SPÖ.

The city has enacted many social democratic policies. The Gemeindebauten are social housing assets that are well integrated into the city architecture outside the first or "inner" district. The low rents enable comfortable accommodation and good access to the city amenities. Many of the projects were built after the Second World War on vacant lots that were destroyed by bombing during the war. The city took particular pride in building them to a high standard. The social housing in Vienna provides living for more than 500,000 people.[78]

Government

Since Vienna obtained federal state (Bundesland) status of its own by the federal constitution of 1920, the city council also functions as the state parliament (Landtag), and the mayor (except 1934–1945) also doubles as the Landeshauptmann (governor/minister-president) of the state of Vienna. The Rathaus accommodates the offices of the mayor (de:Magistrat der Stadt Wien) and the state government (Landesregierung). The city is administered by a multitude of departments (Magistratsabteilungen), politically supervised by Amtsführende Stadträte (members of the city government/parliament leading offices; according to the Vienna constitution opposition parties have the right to designate members of the city government not leading offices).

Under the city constitution of 1920, municipal and state business must be kept separate. Hence, the city council and state parliament hold separate meetings, with separate presiding officers–the chairman of the city council or the president of the state Landtag–even though the two bodies' memberships are identical. When meeting as a city council, the deputies can only deal with the affairs of the city of Vienna; when meeting as a state parliament, they can only deal with the affairs of the state of Vienna.

In the 1996 City Council election, the SPÖ lost its overall majority in the 100-seat chamber, winning 43 seats and 39.15% of the vote. The SPÖ had held an outright majority at every free municipal election since 1919. In 1996 the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), which won 29 seats (up from 21 in 1991), beat the ÖVP into third place for the second time running. From 1996 to 2001, the SPÖ governed Vienna in a coalition with the ÖVP. In 2001 the SPÖ regained the overall majority with 52 seats and 46.91% of the vote; in October 2005, this majority was increased further to 55 seats (49.09%). In course of the 2010 city council elections the SPÖ lost their overall majority again and consequently forged a coalition with the Green Party – the first SPÖ/Green coalition in Austria.[79] This coalition was maintained following the 2015 election. Following the 2020 election, the SPÖ forged a coalition with NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum.[80]

Economy

Vienna generates 28.6% of Austria's gross domestic product (GDP). The service sector dominates Vienna's economy. The average unemployment rate in Vienna is 4.9% and the private service sector provides 75% of all jobs.[81] The city improved its position from 2012 on the ranking of the most economically powerful cities reaching number nine on the listing in 2015.[82][83] Of the top 500 Austrian firms measured by turnover 203 are headquartered in Vienna.[84] The number of international businesses in Vienna is growing. In 2014 159 and in 2015 175 international firms established offices in Vienna.[85]

Since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Vienna has expanded its position as gateway to Eastern Europe. 300 international companies have their Eastern European headquarters in Vienna and its environs. Among them are Hewlett-Packard, Henkel, Baxalta and Siemens.[86]

Approximately 8,300 new companies have been founded in Vienna every year since 2004.[87] The majority of these companies are operating in fields of industry-oriented services, wholesale trade as well as information and communications technologies and new media.[88] Vienna makes effort to establish itself as a start-up hub. Since 2012, the city hosts the annual Pioneers Festival, the largest start-up event in Central Europe with 2,500 international participants taking place at Hofburg Palace. Tech Cocktail, an online portal for the start-up scene, has ranked Vienna sixth among the top ten start-up cities worldwide.[89][90][91]

The cultivation and production of wines within the city borders have a high socio-cultural value.

Research and development

A major R&D sector in Vienna are life sciences. The Vienna Life Science Cluster is Austria's major hub for life science research, education and business. Throughout Vienna, five universities and several basic research institutes form the academic core of the hub with more than 12,600 employees and 34,700 students. Here, more than 480 medical device, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies with almost 23,000 employees generate around 12 billion euros in revenue (2017). This corresponds to more than 50% of the revenue generated by life science companies in Austria (22.4 billion euros).[92][93]

Vienna is home to global players like Boehringer Ingelheim, Octapharma, Ottobock and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.[94] However, there is also a growing number of start-up companies in the life sciences and Vienna was ranked first in the 2019 PeoplePerHour Startup Cities Index.[95] Companies such as Apeiron Biologics, Hookipa Pharma, Marinomed, mySugr, Themis Bioscience and Valneva operate a presence in Vienna and regularly hit the headlines internationally.[96] Vienna also houses the headquarters of the Central European Diabetes Association, a cooperative international medical research association.

To facilitate tapping the economic potential of the multiple facettes of the life sciences at Austria's capital, the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs and the local government of City of Vienna have joined forces: Since 2002, the LISAvienna platform is available as a central contact point. It provides free business support services at the interface of the Austrian federal promotional bank, Austria Wirtschaftsservice and the Vienna Business Agency and collects data that inform policy making.[97] The main academic hot spots in Vienna are the Life Science Center Muthgasse with the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), the Austrian Institute of Technology, the University of Veterinary Medicine, the AKH Vienna with the MedUni Vienna and the Vienna Biocenter.[98] Central European University, a graduate institution expelled from Budapest in the midst of a Hungarian government steps to take control of academic and research organizations, welcomes the first class of students to its new Vienna campus in 2019.[99]

Information technologies

The Viennese sector for information and communication technologies is comparable in size with the sector in Helsinki, Milan or Munich and thus among Europe's largest IT locations. In 2012 8,962 IT businesses with a workforce of 64,223 were located in the Vienna Region. The main products are instruments and appliances for measuring, testing and navigation as well as electronic components. More than ⅔ of the enterprises provide IT services. Among the biggest IT firms in Vienna are Kapsch, Beko Engineering & Informatics, air traffic control experts Frequentis, Cisco Systems Austria, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft Austria, IBM Austria and Samsung Electronics Austria.[100][101]

The US technology corporation Cisco runs its Entrepreneurs in Residence program for Europe in Vienna in cooperation with the Vienna Business Agency.[102][103]

The British company UBM has rated Vienna one of the Top 10 Internet Cities worldwide, by analyzing criteria like connection speed, WiFi availability, innovation spirit and open government data.[104]

Conferences

In 2019 the International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) ranked Vienna 6th in the world for association meetings.[105] The Union of International Associations (UIA) ranked Vienna 5th in the world for 2019 with 306 international meetings, behind Singapore, Brussels, Seoul and Paris.[106] The city's largest conference center, the Austria Center Vienna (ACV) has a total capacity for around 22,800 people and is situated next to the United Nations Office at Vienna.[107] Other centers are the Messe Wien Exhibition & Congress Center (up to 3,000 people) and the Hofburg Palace (up to 4,900 people).

Tourism

There were 17.6 million overnight stays in Vienna in 2019. The top ten incoming markets in 2019 were Germany, Austria, the United States, Italy, United Kingdom, Spain, China, France, Russia and Switzerland.[108]

Rankings

In a 2005 study of 127 world cities, the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked the city first (in a tie with Vancouver and San Francisco) for the world's most livable cities. Between 2011 and 2015, Vienna was ranked second, behind Melbourne.[109] Monocle's 2015 "Quality of Life Survey" ranked Vienna second on a list of the top 25 cities in the world "to make a base within".[110] Monocle's 2012 "Quality of Life Survey" ranked Vienna fourth on a list of the top 25 cities in the world "to make a base within" (up from sixth in 2011 and eighth in 2010).[111] The UN-Habitat classified Vienna as the most prosperous city in the world in 2012–2013.[112] The city was ranked 1st globally for its culture of innovation in 2007 and 2008, and sixth globally (out of 256 cities) in the 2014 Innovation Cities Index, which analyzed 162 indicators in covering three areas: culture, infrastructure, and markets.[113][114][115] Between 2005 and 2010, Vienna was the world's number-one destination for international congresses and conventions.[116] It attracts over 6.8 million tourists a year.[117]

Vienna was ranked top in the 2019 Quality of Living Ranking by the international Mercer Consulting Group for the tenth consecutive year.[118] In the 2015 liveability report by the Economist Intelligence Unit as well as in the Quality of Life Survey 2015 of London-based Monocle magazine Vienna was equally ranked second most livable city worldwide.[119][120]

The United Nations Human Settlements Programme UN-Habitat has ranked Vienna the most prosperous city in the world in its flagship report State of the World Cities 2012/2013.[121]

According to the 2014 City RepTrack ranking by the Reputation Institute, Vienna has the best reputation in comparison with 100 major global cities.[122]

The Innovation Cities Global Index 2014 by the Australian innovation agency 2thinknow ranks Vienna sixth behind San Francisco-San Jose, New York City, London, Boston and Paris.[123] In 2019 PeoplePerHour put Vienna at the top of their Startup Cities Ranking.[124]

US climate strategist Boyd Cohen placed Vienna first in his first global smart cities ranking of 2012. In the 2014 ranking, Vienna reached third place among European cities behind Copenhagen and Amsterdam.[125]

The Mori Memorial Institute for Urban Strategies ranked Vienna in the top ten of their Global Power City Index 2016.[126]

Urban planning

Vienna regularly hosts urban planning conferences and is often used as a case study by urban planners.[127] The highest wooden skyscraper in the world, "HoHo Wien", was built within 3 years, starting in 2015.[128] In recent years a syndicate housing movement has established itself in Vienna, Linz, Salzburg, and Innsbruck.[129]

In 2011 74.3% of Viennese households were connected with broadband, 79% were in possession of a computer. According to the broadband strategy of the city, full broadband coverage will be reached by 2020.[100][101]

Central Railway Station

Vienna's new Central Railway Station was opened in October 2014.[130] Construction began in June 2007 and was due to last until December 2015. The station is served by 1,100 trains with 145,000 passengers. There is a shopping center with approximately 90 shops and restaurants. In the vicinity of the station a new district is emerging with 550,000 m2 (5,920,000 sq ft) office space and 5,000 apartments until 2020.[131][132][133]

Smart City Wien

The mayor of Vienna announced the Smart City Wien initiative in March 2011 after the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund decided to fund a project under the same heading. The Vienna city administration engaged with a broad range of stakeholders and published the Smart City Wien action plan.[134]

Aspern

Seestadt Aspern in Vienna's Donaustadt district is one of the largest urban expansion projects of Europe. A 5 hectare artificial lake, offices, apartments and a subway station within walking distance are supposed to attract 20,000 new citizens when construction is completed in 2028.[135][136]

Culture

Music, theater and opera

Famous composers including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven, Ferdinand Ries, Nina Stollewerk, Franz Schubert, Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler, Robert Stolz, and Arnold Schoenberg have worked in Vienna.

Art and culture had a long tradition in Vienna, including theater, opera, classical music and fine arts. The Burgtheater is considered one of the best theaters in the German-speaking world alongside its branch, the Akademietheater. The Volkstheater Wien and the Theater in der Josefstadt also enjoy good reputations. There is also a multitude of smaller theaters, in many cases devoted to less mainstream forms of the performing arts, such as modern, experimental plays or cabaret.

Vienna is also home to a number of opera houses, including the Theater an der Wien, the Staatsoper and the Volksoper, the latter being devoted to the typical Viennese operetta. Classical concerts are performed at venues such as the Wiener Musikverein, home of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra known across the world for the annual widely broadcast "New Year's Day Concert", as well as the Wiener Konzerthaus, home of the internationally renowned Vienna Symphony. Many concert venues offer concerts aimed at tourists, featuring popular highlights of Viennese music, particularly the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Strauss I, and Johann Strauss II.

Up until 2005, the Theater an der Wien hosted premieres of musicals, but since 2006 (a year dedicated to the 250th anniversary of Mozart's birth), has devoted itself to opera again, becoming a stagione opera house offering one new production each month. Since 2012, Theater an der Wien has taken over the Wiener Kammeroper, a historical small theater in the first district of Vienna seating 300 spectators, turning it into its second venue for smaller sized productions and chamber operas created by the young ensemble of Theater an der Wien (JET). Before 2005 the most successful musical was Elisabeth, which was later translated into several languages and performed all over the world. The Wiener Taschenoper is dedicated to stage music of the 20th and 21st century. The Haus der Musik ("house of music") opened in the year 2000.

The Wienerlied is a unique song genre from Vienna. There are approximately 60,000 – 70,000 Wienerlieder.[137]

In 1981 the popular British new romantic group Ultravox paid a tribute to Vienna on an album and an artful music video recording called Vienna. The inspiration for this work arose from the cinema production called The Third Man with the title Zither music of Anton Karas.

The Vienna's English Theatre (VET) is an English theater in Vienna. It was founded in 1963 and is located in the 8th Vienna's district. It is the oldest English-language theater in continental Europe.

In May 2015, Vienna hosted the Eurovision Song Contest following Austria's victory in the 2014 contest.

Actors from Vienna

Notable entertainers born in Vienna include Hedy Lamarr, Christoph Waltz, John Banner, Christiane Hörbiger, Eric Pohlmann, Boris Kodjoe, Christine Buchegger, Mischa Hausserman, Senta Berger and Christine Ostermayer.

Musicians from Vienna

Notable musicians born in Vienna include Louie Austen, Alban Berg, Falco, Fritz Kreisler, Joseph Lanner, Arnold Schönberg, Franz Schubert, Johann Strauss I, Johann Strauss II, Anton Webern, and Joe Zawinul.

Famous musicians who came here to work from other parts of Austria and Germany were Kurt Adler, Johann Joseph Fux, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Ferdinand Ries, Johann Sedlatzek, Antonio Salieri, Carl Czerny, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Franz Liszt, Franz von Suppé, Anton Bruckner, Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler and Rainhard Fendrich.

Notable writers from Vienna

Notable writers from Vienna include Karl Leopold von Möller, Carl Julius Haidvogel, and Stefan Zweig.

Writers who lived and worked in Vienna include Franz Kafka, Arthur Schnitzler, Elias Canetti, Ingeborg Bachmann, Robert Musil, Karl Kraus, Ernst von Feuchtersleben, Thomas Bernhard and Elfriede Jelinek.

Notable politicians from Vienna

Notable athletes

- David Alaba (born 1992), professional footballer

- Renato Gligoroski (born 1976), former professional footballer, now coach and engineer

- Niki Lauda (1949–2019), three-time Formula One World Drivers' Champion

Museums

The Hofburg is the location of the Imperial Treasury (Schatzkammer), holding the imperial jewels of the Habsburg dynasty. The Sisi Museum (a museum devoted to Empress Elisabeth of Austria) allows visitors to view the imperial apartments as well as the silver cabinet. Directly opposite the Hofburg are the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which houses many paintings by Old Masters, ancient and classical artifacts, and the Naturhistorisches Museum.

A number of museums are located in the MuseumsQuartier (museum quarter), the former Imperial Stalls which were converted into a museum complex in the 1990s. It houses the Museum of Modern Art, commonly known as the MUMOK (Ludwig Foundation), the Leopold Museum (featuring the largest collection of paintings in the world by Egon Schiele, as well as works by the Vienna Secession, Viennese Modernism and Austrian Expressionism), the AzW (museum of architecture), additional halls with feature exhibitions, and the Tanzquartier. The Liechtenstein Palace contains much of one of the world's largest private art collections, especially strong in the Baroque. The Belvedere, built under Prince Eugene, has a gallery containing paintings by Gustav Klimt (The Kiss), Egon Schiele, and other painters of the early 20th century, also sculptures by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, and changing exhibitions too.

There are a multitude of other museums in Vienna, including the Albertina, the Military History Museum, the Technical Museum, the Burial Museum, the Museum of Art Fakes, the KunstHausWien, Museum of Applied Arts, the Sigmund Freud Museum, and the Mozarthaus Vienna. The museums on the history of the city, including the former Historical Museum of the City of Vienna on Karlsplatz, the Hermesvilla, the residences and birthplaces of various composers, the Museum of the Romans, and the Vienna Clock Museum, are now gathered together under the group umbrella Vienna Museum. The Jewish Museum Vienna, founded 1896, is the oldest of its kind. In addition there are museums dedicated to Vienna's individual districts. They provide a record of individual struggles, achievements and tragedy as the city grew and survived two world wars. For readers seeking family histories these are good sources of information.

Architecture

A variety of architectural styles can be found in Vienna, such as the Romanesque Ruprechtskirche and the Baroque Karlskirche. Styles range from classicist buildings to modern architecture. Art Nouveau left many architectural traces in Vienna. The Secession building, Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Station, and the Kirche am Steinhof by Otto Wagner rank among the best known examples of Art Nouveau in the world. Wagner's prominent student Jože Plečnik from Slovenia also left important traces in Vienna. His works include the Langer House (1900) and the Zacherlhaus (1903–1905). Plečnik's 1910–1913 Church of the Holy Spirit (Heilig-Geist-Kirche) in Vienna is remarkable for its innovative use of poured-in-place concrete as both structure and exterior surface, and also for its abstracted classical form language. Most radical is the church's crypt, with its slender concrete columns and angular, cubist capitals and bases.

Concurrent to the Art Nouveau movement was the Wiener Moderne, during which some architects shunned the use of extraneous adornment. A key architect of this period was Adolf Loos, whose works include the Looshaus (1909), the Kärntner Bar or American Bar (1908) and the Steiner House (1910).

The Hundertwasserhaus by Friedensreich Hundertwasser, designed to counter the clinical look of modern architecture, is one of Vienna's most popular tourist attractions. Another example of unique architecture is the Wotrubakirche by sculptor Fritz Wotruba. In the 1990s, a number of quarters were adapted and extensive building projects were implemented in the areas around Donaustadt (north of the Danube) and Wienerberg (in southern Vienna).

The 220-meter high DC Tower 1 located on the Northern bank of the Danube, completed in 2013, is the tallest skyscraper in Vienna.[138][139] In recent years, Vienna has seen numerous architecture projects completed which combine modern architectural elements with old buildings, such as the remodeling and revitalization of the old Gasometer in 2001. Most buildings in Vienna are relatively low; in early 2006 there were around 100 buildings higher than 40 m (130 ft). The number of high-rise buildings is kept low by building legislation aimed at preserving green areas and districts designated as world cultural heritage. Strong rules apply to the planning, authorization and construction of high-rise buildings. Consequently, much of the inner city is a high-rise free zone.

Ball dances of Vienna

Vienna is the last great capital of the 19th-century ball. There are over 450 balls per year, some featuring as many as nine live orchestras.[140] Balls are held in the many palaces in Vienna, with the principal venue being the Hofburg Palace in Heldenplatz. While the Opera Ball is the best known internationally of all the Austrian balls, other balls such as the Kaffeesiederball (Cafe Owners Ball), the Jägerball (Hunter's Ball) and the Life Ball (AIDS charity event) are almost as well known within Austria and even better appreciated for their cordial atmosphere. Viennese of at least middle class may visit a number of balls in their lifetime.

Dancers and opera singers from the Vienna State Opera often perform at the openings of the larger balls.

A Vienna ball is an all-night cultural attraction. Major Vienna balls generally begin at 9 pm and last until 5 am, although many guests carry on the celebrations into the next day. Viennese balls are being exported (with support from the City of Vienna) to around 30 cities worldwide such as New York, Barcelona, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Rome, Prague, Bucharest, Berlin and Moscow.[140][141][142]

Language

Vienna is part of the Austro-Bavarian language area, in particular Central Bavarian (Mittelbairisch).[143] In recent years, linguistics experts have seen a decline in the use of the Viennese variant.[144][145] Manfred Glauninger, sociolinguist at the Institute for Austrian Dialect and Name Lexica, has observed three issues. First, many parents feel there is a stigma attached to the Viennese dialect so they speak Standard German to their children. Second, many children have recently immigrated to Austria and are learning German as a second language in school. Third, young people are influenced by mass media which is almost always delivered in Standard German.[146]

LGBT culture

Vienna is considered the center of LGBT life in Austria.[147] The city has an action plan against queerphobic discrimination and, since 1998, has an anti-discrimination unit within the city's administration.[148] The city has several cafés, bars and clubs frequented by LGBT people. Among the most prominent is Café Savoy, which is a traditional coffee house built in 1896. In 2015, the city introduced traffic lights with same-sex couples before hosting the Eurovision Song Contest that year, which attracted media attention internationally.[149] Every year in June, Vienna Pride is organized. In 2019, when the pride parade was also hosting Europride, it attracted 500.000 visitors.[150][151]

Education

Vienna is Austria's main center of education and home to many universities, professional colleges and high schools.

International schools

Universities

- Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

- Central European University

- Diplomatic Academy of Vienna

- Medical University of Vienna

- PEF Private University of Management Vienna

- University of Applied Arts Vienna

- University of Applied Sciences Campus Vienna

- University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna

- University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna

- University of Vienna

- Vienna University of Economics and Business

- University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna

- University of Applied Sciences Technikum Wien

- TU Wien

- Webster Vienna Private University

- Sigmund Freud University Vienna

- International Anti-Corruption Academy (in Laxenburg, 24 km (15 mi) south of Vienna)

Research institutes

Defunct

Leisure activities

Parks and gardens

Vienna possesses many parks, including the Stadtpark, the Burggarten, the Volksgarten (part of the Hofburg), the Schlosspark at Schloss Belvedere (home to the Vienna Botanic Gardens), the Donaupark, the Schönbrunner Schlosspark, the Prater, the Augarten, the Rathauspark, the Lainzer Tiergarten, the Dehnepark, the Resselpark, the Votivpark, the Kurpark Oberlaa, the Auer-Welsbach-Park and the Türkenschanzpark. Green areas include Laaer-Berg (including the Bohemian Prater) and the foothills of the Wienerwald, which reaches into the outer areas of the city. Small parks, known by the Viennese as Beserlparks, are everywhere in the inner city areas.

Many of Vienna's parks include monuments, such as the Stadtpark with its statue of Johann Strauss II, and the gardens of the baroque palace, where the State Treaty was signed. Vienna's principal park is the Prater which is home to the Riesenrad, a Ferris wheel, and Kugelmugel, a micronation the shape of a sphere. The imperial Schönbrunn's grounds contain an 18th-century park which includes the world's oldest zoo, founded in 1752. The Donauinsel, part of Vienna's flood defenses, is a 21.1 km (13.1 mi) long artificial island between the Danube and Neue Donau dedicated to leisure activities.

Sport

Austria's capital is home to numerous football teams. The best known are the local football clubs include FK Austria Wien (21 Austrian Bundesliga titles and record 27-time cup winners), SK Rapid Wien (record 32 Austrian Bundesliga titles), and the oldest team, First Vienna FC. Other important sports clubs include the Raiffeisen Vikings Vienna (American football), who won the Eurobowl title between 2004 and 2007 4 times in a row and had a perfect season in 2013, the Aon Hotvolleys Vienna, one of Europe's premier Volleyball organizations, the Vienna Wanderers (baseball) who won the 2012 and 2013 Championship of the Austrian Baseball League, and the Vienna Capitals (ice hockey). Vienna was also where the European Handball Federation (EHF) was founded. There are also three rugby clubs; Vienna Celtic, the oldest rugby club in Austria, RC Donau, and Stade Viennois

Vienna hosts many different sporting events including the Vienna City Marathon, which attracts more than 10,000 participants every year and normally takes place in May. In 2005 the ice hockey World Championships took place in Austria and the final was played in Vienna. Vienna's Ernst-Happel-Stadion was the venue of four Champions League and European Champion Clubs' Cup finals (1964, 1987, 1990 and 1995) and on 29 June it hosted the final of Euro 2008 which saw a Spanish 1–0 victory over Germany. Tennis tournament Vienna Open also takes place in the city since 1974. The matches are played in the Wiener Stadthalle.

The Neue Donau, which was formed after the Donauinsel was created, is free of river traffic and a popular destination for leisure and sports activities.

Vienna hosted the official 2021 3x3 Basketball World Cup.[152]

Culinary specialities

Food

Vienna is well known for Wiener schnitzel, a cutlet of veal (Kalbsschnitzel) or pork (Schweinsschnitzel) that is pounded flat, coated in flour, egg and breadcrumbs, and fried in clarified butter. It is available in almost every restaurant that serves Viennese cuisine and can be eaten hot or cold. It is usually served in many cozy cafeterias in the old town evoking all the history behind the Empire city. The traditional 'Wiener Schnitzel' though is a cutlet of veal. Other examples of Viennese cuisine include Tafelspitz (very lean boiled beef), which is traditionally served with Geröstete Erdäpfel (boiled potatoes mashed with a fork and subsequently fried) and horseradish sauce, Apfelkren (a mixture of horseradish, cream and apple) and Schnittlauchsauce (a chives sauce made with mayonnaise and stale bread).

Vienna has a long tradition of producing cakes and desserts. These include Apfelstrudel (hot apple strudel), Milchrahmstrudel (milk-cream strudel), Palatschinken (sweet pancakes), and Knödel (dumplings) often filled with fruit such as apricots (Marillenknödel). Sachertorte, a delicately moist chocolate cake with apricot jam created by the Sacher Hotel, is world-famous.

In winter, small street stands sell traditional Maroni (hot chestnuts) and potato fritters.

Sausages are popular and available from street vendors (Würstelstand) throughout the day and into the night. The sausage known as Wiener (German for Viennese) in the U.S. and in Germany, is called a Frankfurter in Vienna. Other popular sausages are Burenwurst (a coarse beef and pork sausage, generally boiled), Käsekrainer (spicy pork with small chunks of cheese), and Bratwurst (a white pork sausage). Most can be ordered "mit Brot" (with bread) or as a "hot dog" (stuffed inside a long roll). Mustard is the traditional condiment and usually offered in two varieties: "süß" (sweet) or "scharf" (spicy).

Kebab, pizza and noodles are, increasingly, the snack foods most widely available from small stands.

Vienna ranked 10th in vegan friendly European cities in a study by Alternative Traveler.[153]

The Naschmarkt is a permanent market for fruit, vegetables, spices, fish, meat, etc., from around the world. The city has many coffee and breakfast stores.

Drinks

Vienna, along with Paris, Santiago, Cape Town, Prague, Canberra, Bratislava and Warsaw, is one of the few remaining world capital cities with its own vineyards.[154] The wine is served in small Viennese pubs known as Heuriger, which are especially numerous in the wine growing areas of Döbling (Grinzing, Neustift am Walde, Nußdorf, Salmannsdorf, Sievering), Floridsdorf (Stammersdorf, Strebersdorf), Liesing (Mauer) and Favoriten (Oberlaa). The wine is often drunk as a Spritzer ("G'spritzter") with sparkling water. The Grüner Veltliner, a dry white wine, is the most widely cultivated wine in Austria.[155] Another wine very typical for the region is "Gemischter Satz", which is typically a blend of different types of wines harvested from the same vineyard.[156]

Beer is next in importance to wine. Vienna has a single large brewery, Ottakringer, and more than ten microbreweries. A "Beisl" is a typical small Austrian pub, of which Vienna has many.

Also, local soft drinks such as Almdudler are popular around the country as an alternative to alcoholic beverages, placing it on the top spots along American counterparts such as Coca-Cola in terms of market share. Another popular drink is the so-called "Spezi", a mix between Coca-Cola and the original formula of Orange Fanta or the more locally renowned Frucade.

Viennese cafés

Viennese cafés have an extremely long and distinguished history that dates back centuries, and the caffeine addictions of some famous historical patrons of the oldest are something of a local legend. These coffee houses are unique to Vienna and many cities have unsuccessfully sought to copy them. Some people consider cafés as their extended living room where nobody will be bothered if they spend hours reading a newspaper while enjoying their coffee. Traditionally, the coffee comes with a glass of water. Viennese cafés claim to have invented the process of filtering coffee from booty captured after the second Turkish siege in 1683. Viennese cafés claim that when the invading Turks left Vienna, they abandoned hundreds of sacks of coffee beans. The Polish King John III Sobieski, the commander of the anti-Turkish coalition of Poles, Germans, and Austrians, gave Franz George Kolschitzky (Polish – Franciszek Jerzy Kulczycki) some of this coffee as a reward for providing information that allowed him to defeat the Turks. Kolschitzky then opened Vienna's first coffee shop. Julius Meinl set up a modern roasting plant in the same premises where the coffee sacks were found, in 1891.

Tourist attractions

Major tourist attractions include the imperial palaces of the Hofburg and Schönbrunn (also home to the world's oldest zoo, Tiergarten Schönbrunn) and the Riesenrad in the Prater. Cultural highlights include the Burgtheater, the Wiener Staatsoper, the Lipizzaner horses at the spanische Hofreitschule, and the Vienna Boys' Choir, as well as excursions to Vienna's Heurigen district Döbling.

There are also more than 100 art museums, which together attract over eight million visitors per year.[157] The most popular ones are Albertina, Belvedere, Leopold Museum in the Museumsquartier, KunstHausWien, Bank Austria Kunstforum, the twin Kunsthistorisches Museum and Naturhistorisches Museum, and the Technisches Museum Wien, each of which receives over a quarter of a million visitors per year.[158]

There are many popular sites associated with composers who lived in Vienna including Beethoven's various residences and grave at Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) which is the largest cemetery in Vienna and the burial site of many famous people. Mozart has a memorial grave at the Habsburg gardens and at St. Marx Cemetery (where his grave was lost). Vienna's many churches also draw large crowds, famous of which are St. Stephen's Cathedral, the Deutschordenskirche, the Jesuitenkirche, the Karlskirche, the Peterskirche, Maria am Gestade, the Minoritenkirche, the Ruprechtskirche, the Schottenkirche, St. Ulrich and the Votivkirche.

Modern attractions include the Hundertwasserhaus, the United Nations headquarters and the view from the Donauturm.

Transport

Vienna has an extensive transport network with a unified fare system that integrates municipal, regional and railway systems under the umbrella of the Verkehrsverbund Ost-Region (VOR). Public transport is provided by buses, trams and five underground metro lines (U-Bahn), most operated by the Wiener Linien. There are also more than 50 S-train stations within the city limits. Suburban trains are operated by the ÖBB. The city forms the hub of the Austrian railway system, with services to all parts of the country and abroad. The railway system connects Vienna's main station Vienna Hauptbahnhof with other European cities, like Berlin, Bratislava, Budapest, Brussels, Cologne, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Ljubljana, Munich, Prague, Venice, Wrocław, Warsaw, Zagreb and Zürich.

Vienna has multiple road connections including expressways and motorways.

Vienna is served by Vienna International Airport, located 18 km (11 mi) southeast of the city center next to the town of Schwechat. The airport handled approximately 31.7 million passengers in 2019.[159] Following lengthy negotiations with surrounding communities, the airport will be expanded to increase its capacity by adding a third runway. The airport is undergoing a major expansion, including a new terminal building that opened in 2012 to prepare for an increase in passengers. Another possibility is to use Bratislava Airport, Slovakia, located approximately 60 km away.

Viennese

International relations

International organizations in Vienna

Vienna is the seat of a number of United Nations offices and various international institutions and companies, including the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). Vienna is the world's third "UN city", next to New York City, Geneva, and Nairobi. Additionally, Vienna is the seat of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law's secretariat (UNCITRAL). In conjunction, the University of Vienna annually hosts the prestigious Willem C. Vis Moot, an international commercial arbitration competition for students of law from around the world.

Diplomatic meetings have been held in Vienna in the latter half of the 20th century, resulting in documents bearing the name Vienna Convention or Vienna Document. Among the more important documents negotiated in Vienna are the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, as well as the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. Vienna also hosted the negotiations leading to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action on Iran's nuclear program as well as the Vienna peace talks for Syria.

Vienna also headquartered the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF).

Charitable organizations in Vienna

Alongside international and intergovernmental organizations, there are dozens of charitable organizations based in Vienna. One such organization is the network of SOS Children's Villages, founded by Hermann Gmeiner in 1949. Today, SOS Children's Villages are active in 132 countries and territories worldwide. Others include HASCO.

Another popular international event is the annual Life Ball, which supports people with HIV or AIDS. Guests such as Bill Clinton and Whoopi Goldberg were recent attendees.

International city cooperations

The general policy of the City of Vienna is not to sign any twin town agreements with other cities. Instead Vienna has only cooperation agreements in which specific cooperation areas are defined.[160]

District to district partnerships

In addition, individual Viennese districts have international partnerships all over the world. A detailed list is published on the website of the City of Vienna.[161]

See also

References

- "Dauersiedlungsraum der Gemeinden, Politischen Bezirke und Bundesländer, Gebietsstand 1.1.2019". Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Becoming a Minority Project. "Vienna – BAM – Becoming a Minority". bamproject.eu. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- "Postlexikon". Post AG. 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historic Centre of Vienna inscribed on List of World Heritage in Danger". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2

- "Bevölkerung zu Jahres-/Quartalsanfang" [Population at the beginning of the year/quarter]. Statistik Austria. 1 April 2022. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Population on 1 January by broad age group, sex and metropolitan regions". Eurostat. 4 May 2022. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Vienna after the war" Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 29 December 1918 (PDF)

- "Wien nun zweitgrößte deutschsprachige Stadt | touch.ots.at". Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Ergebnisse Zensus 2011" (in German). Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "Historic Centre of Vienna". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "Vienna – the City of Music – Vienna – Now or Never". Wien.info. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- BBC Documentary – Vienna – The City of Dreams

- "Historic Centre of Vienna". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Csendes, Peter (2001). "Das Werden Wiens – Die siedlungsgeschichtlichen Grundlagen". In Csendes, Peter; Oppl, F. (eds.). Wien – Geschichte einer Stadt von den Anfängen zur Ersten Türkenbelagerung (in German). Vienna: Böhlau. pp. 55–94, here p. 57.

- Pleyel, Peter (2002). Das römische Österreich. Vienna: Pichler. p. 83. ISBN 3-85431-270-9.

- Mosser, Martin; Fischer-Ausserer, Karin, eds. (2008). Judenplatz. Die Kasernen des römischen Legionslagers. Wien Archäologisch (in German). Vol. 5. Vienna: Stadtarchäologie Wien. p. 11.

- "Vienna". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Mac Cana, Proinsias. "Fianaigecht in the Pre-Norman Period". In: Béaloideas 54/55 (1986): 76. doi:10.2307/20522282. Mac Cana, Proinsias (1986). "Fianaigecht in the Pre-Norman Period". Béaloideas. 54/55: 75–99. doi:10.2307/20522282. JSTOR 20522282. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022..

- FitzPatrick, Elizabeth; Hennessy, Ronan (2017). "Finn's Seat: topographies of power and royal marchlands of Gaelic polities in medieval Ireland". In: Landscape History, 38:2, 31. doi:10.1080/01433768.2017.1394062

- Haberl, Johanna (1976). Favianis, Vindobona und Wien, eine archäologisch-historische Illustration zur Vita S. Severini des Eugippius (in German). Leiden: Brill Academic. p. 125. ISBN 90-04-04548-1.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 52.

- "Vienna – History | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Lingelbach, William E. (1913). The History of Nations: Austria-Hungary. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company. pp. 91–92. ASIN B000L3E368.