Chlorhexidine

Chlorhexidine (CHX)[1] (commonly known by the salt forms chlorhexidine gluconate and chlorhexidine digluconate (CHG) or chlorhexidine acetate) is a disinfectant and antiseptic that is used for skin disinfection before surgery and to sterilize surgical instruments.[2] It may be used both to disinfect the skin of the patient and the hands of the healthcare providers.[3] It is also used for cleaning wounds, preventing dental plaque, treating yeast infections of the mouth, and to keep urinary catheters from blocking.[3] It is used as a liquid or powder.[2][3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | klɔː(r)ˈhɛksɪdiːn |

| Trade names | Betasept, ChloraPrep, Chlorostat, others |

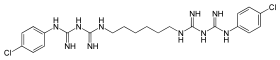

| Other names | 1,6-bis(4-chloro-phenylbiguanido)hexane |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Topical, oral gel |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.217 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H30Cl2N10 |

| Molar mass | 505.45 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 134 to 136 °C (273 to 277 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 0.8 |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects may include skin irritation, teeth discoloration, and allergic reactions,[3] although the risk appears to be the same as other topical antiseptics.[4][5] It may cause eye problems if direct contact occurs.[6] Use in pregnancy appears to be safe.[7] Chlorhexidine may come mixed in alcohol, water, or surfactant solution.[3] It is effective against a range of microorganisms, but does not inactivate spores.[2]

Chlorhexidine came into medical use in the 1950s.[8] Chlorhexidine is available over the counter (OTC) in the United States.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] In 2017, it was the 286th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[10][11]

The name "chlorhexidine" breaks down as chlor(o) + hex(ane) + id(e) + (am)ine.

Uses

Chlorhexidine is used in disinfectants (disinfection of the skin and hands), cosmetics (additive to creams, toothpaste, deodorants, and antiperspirants), and pharmaceutical products (preservative in eye drops, active substance in wound dressings and antiseptic mouthwashes).[12] A 2019 Cochrane review concluded that based on very low certainty evidence in those who are critically ill "it is not clear whether bathing with chlorhexidine reduces hospital‐acquired infections, mortality, or length of stay in the ICU, or whether the use of chlorhexidine results in more skin reactions."[13]

In endodontics, chlorhexidine is used for root canal irrigation and as an intracanal dressing,[14][15][16] but has been replaced by the use of sodium hypochlorite bleach in much of the developed world.

Antiseptic

CHG is active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms, facultative anaerobes, aerobes, and yeasts.[17] It is particularly effective against Gram-positive bacteria (in concentrations ≥ 1 μg/L). Significantly higher concentrations (10 to more than 73 μg/mL) are required for Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Chlorhexidine is ineffective against polioviruses and adenoviruses. The effectiveness against herpes viruses has not yet been established unequivocally.[18]

There is strong evidence that chlorhexidine is more effective than povidone-iodine for clean surgery.[19][20] Evidence shows that it is the most effective antiseptic for upper limb surgery,[4] and there is no data to suggest that alcoholic chlorhexidine increases the risk of tourniquet-related burns, ignition fires or allergic episodes during surgery.

Chlorhexidine, like other cation-active compounds, remains on the skin. It is frequently combined with alcohols (ethanol and isopropyl alcohol).

Dental use

Use of a CHG-based mouthwash in combination with normal tooth care can help reduce the build-up of plaque and improve mild gingivitis.[21] There is not enough evidence to determine the effect in moderate to severe gingivitis.[21] About 20 mL twice a day of concentrations of 0.1% to 0.2% is recommended for mouth-rinse solutions with a duration of at least 30 seconds.[21] Such mouthwash also has a number of adverse effects including damage to the mouth lining, tooth discoloration, tartar build-up, and impaired taste.[21] Extrinsic tooth staining occurs when chlorhexidine rinse has been used for 4 weeks or longer.[21]

Mouthwashes containing chlorhexidine which stain teeth less than the classic solution have been developed, many of which contain chelated zinc.[22][23][24]

Using chlorhexidine as a supplement to everyday mechanical oral hygiene procedures for 4 to 6 weeks and 6 months leads to a moderate reduction in gingivitis compared to placebo, control or mechanical oral hygiene alone.[21]

Chlorhexidine is a cation which interacts with anionic components of toothpaste, such as sodium lauryl sulfate and sodium monofluorophosphate, and forms salts of low solubility and antibacterial activity. Hence, to enhance the antiplaque effect of chlorhexidine, "it seems best that the interval between toothbrushing and rinsing with CHX [chlorhexidine] be more than 30 minutes, cautiously close to 2 hours after brushing".[25]

Topical

Chlorhexidine gluconate is used as a skin cleanser for surgical scrubs, as a cleanser for skin wounds, for preoperative skin preparation, and for germicidal hand rinses.[17] Chlorhexidine eye drops have been used as a treatment for eyes affected by Acanthamoeba keratitis.[26]

Chlorhexidine is very effective for poor countries like Nepal and its use is growing in the world for treating the umbilical cord. A 2015 Cochrane review has yielded high-quality evidence that within the community setting, chlorhexidine skin or cord care can reduce the incidence of omphalitis (inflammation of the umbilical cord) by 50% and neonatal mortality by 12%.[27]

Side effects

CHG is ototoxic; if put into an ear canal which has a ruptured eardrum, it can lead to deafness.[28]

CHG does not meet current European specifications for a hand disinfectant. Under the test conditions of the European Standard EN 1499, no significant difference in the efficacy was found between a 4% solution of chlorhexidine digluconate and soap.[18] In the U.S., between 2007 and 2009, Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Administration Medical Center conducted a cluster-randomized trial and concluded that daily bathing of patients in intensive care units with washcloths saturated with chlorhexidine gluconate reduced the risk of hospital-acquired infections.[29]

Whether prolonged exposure over many years may have carcinogenic potential is still not clear. The US Food and Drug Administration recommendation is to limit the use of a chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash to a maximum of six months.[30]

When ingested, CHG is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and can cause stomach irritation or nausea.[31][32] If aspirated into the lungs at high enough concentration, as reported in one case, it can be fatal due to the high risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome.[32][33]

Mechanism of action

At physiologic pH, chlorhexidine salts dissociate and release the positively charged chlorhexidine cation. The bactericidal effect is a result of the binding of this cationic molecule to negatively charged bacterial cell walls. At low concentrations of chlorhexidine, this results in a bacteriostatic effect; at high concentrations, membrane disruption results in cell death.[17]

Chemistry

It is a cationic polybiguanide (bisbiguanide).[34] It is used primarily as its salts (e.g., the dihydrochloride, diacetate, and digluconate).

Deactivation

Chlorhexidine is deactivated by forming insoluble salts with anionic compounds, including the anionic surfactants commonly used as detergents in toothpastes and mouthwashes, anionic thickeners such as carbomer, and anionic emulsifiers such as acrylates/C10-30 alkyl acrylate crosspolymer, among many others. For this reason, chlorhexidine mouth rinses should be used at least 30 minutes after other dental products.[35] For best effectiveness, food, drink, smoking, and mouth rinses should be avoided for at least one hour after use. Many topical skin products, cleansers, and hand sanitizers should also be avoided to prevent deactivation when chlorhexidine (as a topical by itself or as a residue from a cleanser) is meant to remain on the skin.

Synthesis

The structure is based on two molecules of proguanil, linked with a hexamethylenediamine spacer.

Brands

Chlorhexidine topical is sold as Betasept, Biopatch, Calgon Vesta, ChloraPrep One-Step, Dyna-Hex, Hibiclens, Hibistat Towelette, Scrub Care Exidine, Spectrum-4 among others.[37]

Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash is sold as Dentohexinm, Paroex, Peridex, PerioChip, Corsodyl and Periogard, among others.[38]

Hexoralettene N contains benzocaine, menthol and chlorhexidine hydrochloride. It is used as oral antiseptic candies.

Veterinary medicine

In animals, chlorhexidine is used for topical disinfection of wounds,[39] and to manage skin infections.[40] Chlorhexidine-based disinfectant products are used in the dairy farming industry.[41]

Post-surgical respiratory problems have been associated with the use of chlorhexidine products in cats.[42]

See also

- Polyaminopropyl biguanide

- Polyhexanide

- Triclosan

References

- Varoni, E.; Tarce, M.; Lodi, G.; Carrassi, A. (September 2012). "Chlorhexidine (CHX) in dentistry: state of the art". Minerva Stomatologica. 61 (9): 399–419. ISSN 0026-4970. PMID 22976567.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 321–22. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 568, 791, 839. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Wade, Ryckie G; Bourke, Gráinne; Wormald, Justin C R (9 November 2021). "Chlorhexidine versus povidone–iodine skin antisepsis before upper limb surgery (CIPHUR): an international multicentre prospective cohort study". BJS Open. 5 (6): zrab117. doi:10.1093/bjsopen/zrab117. PMC 8677347. PMID 34915557.

- Wade, Ryckie G.; Burr, Nicholas E.; McCauley, Gordon; Bourke, Grainne; Efthimiou, Orestis (December 2021). "The Comparative Efficacy of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Povidone-iodine Antiseptics for the Prevention of Infection in Clean Surgery: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". Annals of Surgery. 274 (6): e481–e488. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004076. PMID 32773627. S2CID 225289226.

- Briggs, Gerald G.; Freeman, Roger K.; Yaffe, Sumner J. (2011). Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 252. ISBN 9781608317080. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13.

- Schmalz, Gottfried; Bindslev, Dorthe Arenholt (2008). Biocompatibility of Dental Materials. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 351. ISBN 9783540777823. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Chlorhexidine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Thomas Güthner; et al. (2007), "Guanidine and Derivatives", Ullman's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, p. 13

- Lewis, Sharon R.; Schofield-Robinson, Oliver J.; Rhodes, Sarah; Smith, Andrew F. (30 August 2019). "Chlorhexidine bathing of the critically ill for the prevention of hospital‐acquired infection". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD012248. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012248.pub2. PMC 6718196. PMID 31476022.

- Raab D: Preparation of contaminated root canal systems – the importance of antimicrobial irrigants. DENTAL INC 2008: July / August 34–36.

- Raab D, Ma A: Preparation of contaminated root canal systems – the importance of antimicrobial irrigants. 经感染的根管系统的修复 – 化学冲洗对根管治疗的重要性DENTAL INC Chinese Edition 2008: August 18–20.

- Raab D: "Die Bedeutung chemischer Spülungen in der Endodontie". Endodontie Journal 2010: 2; 22–23. http://www.oemus.com/archiv/pub/sim/ej/2010/ej0210/ej0210_22_23_raab.pdf

- Leikin, Jerrold B.; Paloucek, Frank P., eds. (2008), "Chlorhexidine Gluconate", Poisoning and Toxicology Handbook (4th ed.), Informa, pp. 183–84

- Hans-P. Harke (2007), "Disinfectants", Ullman's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 10–11

- Wade, Ryckie G.; Burr, Nicholas E.; McCauley, Gordon; Bourke, Grainne; Efthimiou, Orestis (1 September 2020). "The Comparative Efficacy of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Povidone-iodine Antiseptics for the Prevention of Infection in Clean Surgery: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". Annals of Surgery. Publish Ahead of Print (6): e481–e488. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004076. PMID 32773627.

- Dumville, JC; McFarlane, E; Edwards, P; Lipp, A; Holmes, A; Liu, Z (21 April 2015). "Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003949. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003949.pub4. PMC 6485388. PMID 25897764.

- James P, Worthington HV, Parnell C, Harding M, Lamont T, Cheung A, Whelton H, Riley P (2017). "Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (12): CD008676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008676.pub2. PMC 6464488. PMID 28362061.

- Bernardi F, Pincelli MR, Carloni S, Gatto MR, Montebugnoli L (August 2004). "Chlorhexidine with an Anti Discoloration System. A comparative study". International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2 (3): 122–26. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2004.00083.x. PMID 16451475.

- Sanz, M.; Vallcorba, N.; Fabregues, S.; Muller, I.; Herkstroter, F. (1994). "The effect of a dentifrice containing chlorhexidine and zinc on plaque, gingivitis, calculus and tooth staining". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 21 (6): 431–37. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.1994.tb00741.x. PMID 8089246.

- Kumar, S; Patel, S; Tadakamadla, J; Tibdewal, H; Duraiswamy, P; Kulkarni, S (2013). "Effectiveness of a mouthrinse containing active ingredients in addition to chlorhexidine and triclosan compared with chlorhexidine and triclosan rinses on plaque, gingivitis, supragingival calculus and extrinsic staining". International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 11 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2012.00560.x. PMID 22672130.

- Kolahi, J; Soolari, A (September 2006). "Rinsing with chlorhexidine gluconate solution after brushing and flossing teeth: a systematic review of effectiveness". Quintessence International. 37 (8): 605–12. PMID 16922019.

- Alkharashi M, Lindsley K, Law HA, Sikder S (2015). "Medical interventions for acanthamoeba keratitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2 (2): CD0010792. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010792.pub2. PMC 4730543. PMID 25710134.

- Sinha A, Sazawal S, Pradhan A, Ramji S, Opiyo N (2015). "Chlorhexidine skin or cord care for prevention of mortality and infections in neonates". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD007835. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007835.pub2. PMID 25739381. S2CID 16586836.

- Lai, P; Coulson, C; Pothier, D. D; Rutka, J (2011). "Chlorhexidine ototoxicity in ear surgery, part 1: Review of the literature". Journal of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery. 40 (6): 437–40. PMID 22420428.

- "Daily Bathing With Antiseptic Agent Significantly Reduces Risk of Hospital-Acquired Infections in Intensive Care Unit Patients". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014-04-23. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Below, H.; Assadian, O.; Baguhl, R.; Hildebrandt, U.; Jäger, B.; Meissner, K.; Leaper, D.J.; Kramer, A. (2017). "Measurements of chlorhexidine, p-chloroaniline, and p-chloronitrobenzene in saliva after mouth wash before and after operation with 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate in maxillofacial surgery: a randomised controlled trial". British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 55 (2): 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.10.007. PMID 27789177.

- "Chlorhexidine Adverse Effects". www.poison.org. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- Pubchem. "Chlorhexidine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- Hirata, Kiyotaka; Kurokawa, Akira (April 2002). "Chlorhexidine gluconate ingestion resulting in fatal respiratory distress syndrome". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 44 (2): 89–91. ISSN 0145-6296. PMID 11931511.

An 80-y-old woman with dementia accidentally ingested approximately 200 mL of Maskin (5% CHG) in a nursing home and then presumably aspirated gastric contents.

- Tanzer JM, Slee AM, Kamay BA (1977). "Structural requirements of guanide, biguanide, and bisbiguanide agents for antiplaque activity". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 12 (6): 721–9. doi:10.1128/aac.12.6.721. PMC 430011. PMID 931371.

- Denton, Graham W (2000). "Chlorhexidine". In Block, Seymour S (ed.). Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 321–36. ISBN 978-0-683-30740-5.

- Rose, F. L.; Swain, G. (1956). "850. Bisdiguanides having antibacterial activity". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 4422. doi:10.1039/JR9560004422.

- "Hibiclens Uses, Side Effects & Warnings - Drugs.com". Drugs.com.

- "Chlorhexidine gluconate Uses, Side Effects & Warnings - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- van Hengel, Tosca; ter Haar, Gert; Kirpensteijn, Jolle (2013). "Chapter 2. Wound management: a new protocol for dogs and cats. Chlorhexidine solution". In Kirpensteijn, Jolle; ter Haar, Gert (eds.). Reconstructive Surgery and Wound Management of the Dog and Cat. CRC Press. ISBN 9781482261455.

- Maddison, Jill E.; Page, Stephen W.; Church, David B., eds. (2008). "Antimicrobial agents. Chlorhexidine". Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 552. ISBN 978-0702028588.

- Blowey, Roger William; Edmondson, Peter (2010). Mastitis Control in Dairy Herds. CABI. p. 120. ISBN 9781845937515.

- Zeman, D; Mosley, J; Leslie-Steen, P (Winter 1996). "Post-Surgical Respiratory Distress in Cats Associated with Chlorhexidine Surgical Scrubs". ADDL Newsletters. Indiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

External links

- "Chlorhexidine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.