Hyphema

| Hyphema | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hyphaema, anterior chamber hemorrhage | |

| |

| Hyphema - occupying half of anterior chamber of eye | |

| Specialty | Opthalmology |

| Symptoms | Blurry vision, pain with lights, visible blood[1] |

| Complications | Glaucoma, permanent vision loss[2] |

| Types | Grade 0 to IV[2] |

| Causes | Injury to the eye, spontaneously[2] |

| Risk factors | Leukemia, hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, anticoagulants[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Open globe, vitreous bleed, corneal abrasion, iritis[3] |

| Treatment | Raised head of bed, pain medication, ophthalmology follow-up[2] |

| Frequency | 12 per 100,000 per year[2] |

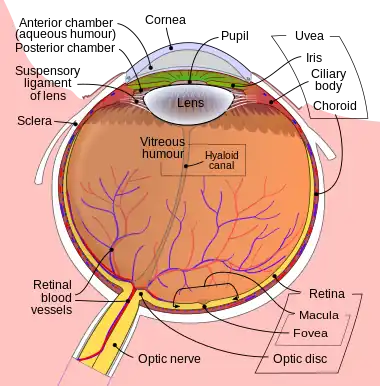

Hyphema is when blood enters the front (anterior) chamber of the eye, the area between the iris and the cornea.[4] Symptoms often include blurry vision and pain with bright light.[1] A layer of blood may be seen in the lower part of the eye when a person is standing.[1] Complications may include glaucoma and permanent vision loss.[2]

It most commonly occurs due to a direct injury to the eye; though may occasionally occur spontaneously.[2] Common types of direct injury including getting hit by a ball in sports and assault.[2] Risk factors include leukemia, hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, and being on anticoagulant medication.[2] The underlying mechanism involves bleeding from the ciliary body or iris.[2] Diagnosis is based on examination, including by slit lamp.[3]

Management involves raising the head of the bed more than 30 degrees, including during sleep, an eye shield, and close follow up by an ophthalmologist.[2] Medication to manage pain and nausea may also be required.[2] This may include cyclopentolate eye drops to prevent the pupil from moving, as long as the intraocular pressure is normal.[2] Bleeding disorder may also require treatment.[2] For those with high intraocular pressures or who are not improving, surgery may be recommended.[2]

Most people, especially those with smaller bleeds, recover fully.[2] In those with less than 33% involvement recovery is about 90%, while this decreases to about 50 to 75% when the entire anterior chamber is full of blood.[2] Hyphema affects about 12 per 100,000 per year.[2] Most cases (about 70%) occur in children.[2] Males are affected more commonly than females.[2]

Signs and symptoms

A decrease or loss of vision is often the first sign.[4] People with microhyphema may have slightly blurred or normal vision. A person with a full hyphema may not be able to see at all.[4]

The person's vision may improve over time as the blood moves by gravity lower in the anterior chamber of the eye, between the iris and the cornea.[4] In many people, the vision will improve, however some may have other injuries related to trauma to the eye or complications related to the hyphema.[4] A microhyphema, where red blood cells are hanging in the anterior chamber of the eye, is less severe. A layered hyphema were fresh blood is seen lower in the anterior chamber is moderately severe. A full hyphema (total hyphema), when blood fills up the chamber completely, is the most severe.[4]

Small hyphema (grade I)

Small hyphema (grade I) Near total hyphema (grade IV)

Near total hyphema (grade IV)

Complications

While the vast majority resolve on their own without issue, sometimes complications occur.[4] Traumatic hyphema may lead to increased intraocular pressure (IOP), peripheral anterior synechiae, atrophy of the optic nerve, staining of the cornea with blood, re-bleeding, and impaired accommodation.[5]

Secondary hemorrhage or rebleeding, is thought to worsen outcomes in terms of visual function and increase the risk of complications such as glaucoma, corneal staining, optic atrophy, or vision loss.[4] Rebleeding occurs in 4–35% of cases.[6] Young children with traumatic hyphema are at an increased risk of developing amblyopia, an irreversible condition.[4]

Causes

Hyphemas are frequently caused by injury, and may partially or completely block vision. The most common causes of hyphema are intraocular surgery, blunt trauma, and lacerating trauma. Hyphemas may also occur spontaneously, without any inciting trauma. Spontaneous hyphemas are usually caused by the abnormal growth of blood vessels (neovascularization), tumors of the eye (retinoblastoma or iris melanoma), uveitis, or vascular anomalies (juvenile xanthogranuloma).[7] Additional causes of spontaneous hyphema include: rubeosis iridis, myotonic dystrophy, leukemia, hemophilia, and von Willebrand disease.[5] Conditions or medications that cause thinning of the blood, such as aspirin, warfarin, or drinking alcohol may also cause hyphema. Source of bleeding in hyphema with blunt trauma to eye is circulus iridis major artery.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on examination, including by slit lamp.[3]

Grades

Grade 0 or microhyphema occurs with scattered RBCs in the anterior chamber that do not layer out.[2] Grade I hyphema has less than 33% anterior chamber filling.[2] Grade II has 33% to 50% filling. Grade III has greater than 50%, but less than total filling of the anterior chamber, and grade IV has 100% anterior chamber filling.[2]

Treatment

The main goals of treatment are to decrease the risk of re-bleeding within the eye, corneal blood staining, and atrophy of the optic nerve. Small hyphemas can usually be treated on an outpatient basis. There is little evidence that most of the commonly used treatments for hyphema (antifibrinolytic agents [oral and systemic aminocaproic acid, tranexamic acid, and aminomethylbenzoic acid], corticosteroids [systemic and topical], cycloplegics, miotics, aspirin, conjugated estrogens, traditional Chinese medicine, monocular versus bilateral patching, elevation of the head, and bed rest) are effective at improving visual acuity after two weeks.[4] Surgery may be necessary for non-resolving hyphemas, or hyphemas that are associated with high pressure that does not respond to medication. Surgery can be effective for cleaning out the anterior chamber and preventing corneal blood staining.[5]

If pain management is necessary, acetaminophen can be used. Aspirin and ibuprofen should be avoided, because they interfere with platelets' ability to form a clot and consequently increase the risk of additional bleeding.[8] Sedation is not usually necessary for patients with hyphema.

Aminocaproic or tranexamic acids are often prescribed for hyphema on the basis that they reduce the risk of rebleeding by inhibiting the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, and thereby keeping clots stable.[6] However, the evidence for their effectiveness is limited and aminocaproic acid may actually cause hyphemas to take longer to clear.[4]

Prognosis

Hyphemas require urgent assessment by an optometrist or ophthalmologist as they may result in permanent visual impairment.

A long-standing hyphema may result in hemosiderosis and heterochromia. Blood accumulation may also cause an elevation of the intraocular pressure. On average, the increased pressure in the eye remains for six days before dropping.[7] Most uncomplicated hyphemas resolve within 5–6 days.[7]

Epidemiology

As of 2012, the rate of hyphemas in the United States are about 20 cases per 100,000 people annually.[7] The majority of people with a traumatic hyphema are children and young adults.[4] 60% of traumatic hyphemas are sports-related, and there are more cases in males compared to females.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Hyphema - Injuries and Poisoning". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Gragg, J; Blair, K; Baker, MB (January 2022). "Hyphema". PMID 29939579.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 DFAAPA, James Van Rhee, MS, PA-C.; DFAAPA, Christine Bruce, DMSc, MHSA, PA-C.; PA-C, Stephanie Neary, MPA, MMS (5 February 2022). Clinical Medicine for Physician Assistants. Springer Publishing Company. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8261-8243-2. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gharaibeh, Almutez; Savage, Howard I.; Scherer, Roberta W.; Goldberg, Morton F.; Lindsley, Kristina (2019). "Medical interventions for traumatic hyphema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD005431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005431.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6353164. PMID 30640411.

- 1 2 3 Walton, William; Von Hagen, Stanley; Grigorian, Ruben; Zarbin, Marco (July–August 2002). "Management of Traumatic Hyphema". Survey of Ophthalmology. 47 (4): 297–334. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00317-X. PMID 12161209. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- 1 2 Recchia, Franco M.; Aaberg Jr., Thomas; Sternberg Jr., Paul (2006-01-01). Hinton, David R.; Schachat, Andrew P.; Wilkinson, C. P. (eds.). Chapter 140 - Trauma: Principles and Techniques of Treatment A2 - Ryan, Stephen J. Edinburgh: Mosby. pp. 2379–2401. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-02598-0.50146-4. ISBN 9780323025980.

- 1 2 3 4 Sheppard, John D. "Hyphema". WebMD, LLC. Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Crawford, JS; Lewandowski, RL; Chan, W (September 1975). "The effect of aspirin on rebleeding in traumatic hyphema". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 80 (3 Pt 2): 543–5. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(75)90224-X. PMC 1311523. PMID 1163602.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |