Rhinitis

| Rhinitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Coryza[1] | |

| |

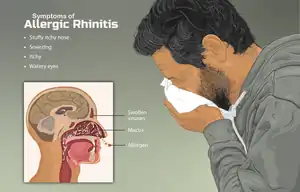

| Allergic rhinitis, a type of rhinitis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, allergist |

| Symptoms | Stuffy nose, runny nose,[4] sneezing[5] |

| Duration | Acute, chronic[4] |

| Types | Allergic, infectious, non-allergic, anatomic[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[5] |

| Treatment | Avoiding triggers, antihistamines, nasal steroids, immunotherapy[7] |

| Frequency | Very common[7] |

Rhinitis, also known as coryza, is swelling and inflammation of the mucous membranes inside the nose, resulting in the feeling of a runny or stuffy nose.[4] Other symptoms may include an itchy nose or eyes, watery eyes, or sneezing.[5][8][9] It can negatively affect quality of life.[7]

The most common causes are allergies and the common cold.[5] Other causes may include irritants like smoke or weather changes.[7] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms.[5] It is divided into four main groups allergic, infectious, non-allergic, and anatomical.[6] Non-allergic includes vasomotor; irritant; drug-induced, including rhinitis medicamentosa; hormonal; atrophic; CSF leak; and nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome (NARES).[9][6]

Treatment of allergic disease includes avoiding triggers, antihistamines, nasal steroids, and immunotherapy.[7][5] Nasal steroids may also be used for non-allergic cases.[7] Nasal decongestant should not be used for more than 3 or 4 days.[5]

Rhinitis is very common.[7] In the United States allergic rhinitis is estimated to affect up to 58 million people while non-allergic rhinitis is estimated to affect up to 30 million people.[6] Vasomotor rhinitis is the most common non-allergic type.[6] About a third of cases may have a mix of nonallergic and allergic rhinitis.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Rhinitis is swelling and inflammation of the mucous membranes inside the nose.[5][7] Symptoms may include stuffy nose, runny nose, nasal itching, and sneezing.[5][8]

Types

Rhinitis may be categorized into four main types: (i) infectious rhinitis; (ii) allergic rhinitis; (iii) nonallergic rhinitis including vasomotor (idiopathic), hormonal, atrophic, gustatory, and drug-induced including rhinitis medicamentosa; (iv) anatomic or structural.[6] Non-allergic can co-exist with allergic rhinitis, and is referred to as "mixed rhinitis".[10]

Infectious

Rhinitis is commonly caused by a viral or bacterial infection, including the common cold, which is caused by Rhinoviruses, Coronaviruses, and influenza viruses, others caused by adenoviruses, human parainfluenza viruses, human respiratory syncytial virus, enteroviruses other than rhinoviruses, metapneumovirus, and measles virus, or bacterial sinusitis, which is commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Symptoms of the common cold include rhinorrhea, sneezing, sore throat (pharyngitis), cough, congestion, and slight headache.[11]

Allergic

Allergic rhinitis, also known as hay fever, may follow when an allergen such as pollen, dust, or Balsam of Peru[12] is inhaled by an individual with a sensitized immune system, triggering antibody production. These antibodies mostly bind to mast cells, which contain histamine. When the mast cells are stimulated by an allergen, histamine (and other chemicals) are released. This causes itching, swelling, and mucus production.

Symptoms vary in severity between individuals. Very sensitive individuals can experience hives or other rashes. Particulate matter in polluted air and chemicals such as chlorine and detergents, which can normally be tolerated, can greatly aggravate the condition.

Characteristic physical findings in individuals who have allergic rhinitis include conjunctival swelling and erythema, eyelid swelling, lower eyelid venous stasis, lateral crease on the nose, swollen nasal turbinates, and middle ear effusion.[13]

Even if a person has negative skin-prick, intradermal and blood tests for allergies, they may still have allergic rhinitis, from a local allergy in the nose. This is called local allergic rhinitis.[14] Many people who were previously diagnosed with nonallergic rhinitis may actually have local allergic rhinitis.[15]

A patch test may be used to determine if a particular substance is causing the rhinitis.

Nonallergic

The first type identified was vasomotor rhinitis, due to vasodilation as a result of overactive parasympathetic nerve response. As additional causes were identified, additional types of nonallergic rhinitis were recognized. Vasomotor rhinitis is also known as nonallergic rhinopathy (NAR) and idiopathic nonallergic rhinitis.[6] The diagnosis is made upon excluding allergic causes.[16] It is an umbrella term of rhinitis of multiple causes, such as occupational (chemical), smoking, gustatory, hormonal, senile (rhinitis of the elderly), atrophic, medication-induced (including rhinitis medicamentosa), local allergic rhinitis, non-allergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome (NARES) and idiopathic (vasomotor or non-allergic, non-infectious perennial allergic rhinitis (NANIPER), or non-infectious non-allergic rhinitis (NINAR).[17]

Vasomotor

In vasomotor rhinitis, certain nonspecific stimuli, including changes in environment (temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, or weather), airborne irritants (odors, fumes), dietary factors (spicy food, alcohol), sexual arousal, exercise, and emotional factors trigger rhinitis.[18][19][20][21] It is thought that these non-allergic triggers cause dilation of the blood vessels in the lining of the nose, which results in swelling and drainage.

Vasomotor rhinitis appears to be more common in women than men, leading some researchers to believe that hormone imbalance plays a role.[22][23] In general, age of onset occurs after 20 years of age, in contrast to allergic rhinitis which can be developed at any age. Individuals with vasomotor rhinitis typically experience symptoms year-round, though symptoms may be exacerbated in the spring and autumn when rapid weather changes are more common.[24] An estimated 17 million United States citizens have vasomotor rhinitis.[24]

Drug induced

Drinking alcohol may cause rhinitis as well as worsen asthma (see alcohol-induced respiratory reactions). In certain populations, particularly those of East Asian countries such as Japan, these reactions have a nonallergic basis.[25] In these cases, alcohol-induced rhinitis may be of the mixed rhinitis type and, it seems likely, most cases of alcohol-induced rhinitis in non-Asian populations reflect true allergic response to the non-ethanol and/or contaminants in alcoholic beverages, particularly when these beverages are wines or beers.[25]

Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly those that inhibit cyclooxygenase 1 (COX1), can worsen rhinitis and asthma symptoms in individuals with a history of either one of these diseases.[26] These exacerbations most often appear due to NSAID hypersensitivity reactions rather than NSAID-induced allergic reactions.[27]

Rhinitis medicamentosa

Rhinitis medicamentosa is a form of drug-induced nonallergic rhinitis which is associated with nasal congestion brought on by the use of certain oral medications (primarily sympathomimetic amine and 2-imidazoline derivatives) and topical decongestants (e.g., oxymetazoline, phenylephrine, xylometazoline, and naphazoline nasal sprays) that constrict the blood vessels in the lining of the nose.[28]

Atrophic

Chronic rhinitis is a form of atrophy of the mucous membrane and glands of the nose.

Structural

Chronic rhinitis associated with polyps in the nasal cavity. This group also includes nasal foreign bodies.[9]

Pathophysiology

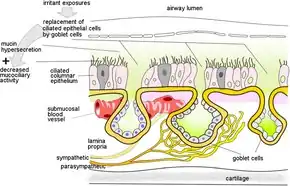

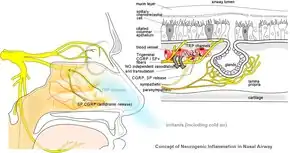

Most prominent pathological changes observed are nasal airway epithelial metaplasia in which goblet cells replace ciliated columnar epithelial cells in the nasal mucous membrane.[29] This results in mucin hypersecretion by goblet cells and decreased mucociliary activity. Nasal secretion are not adequately cleared with clinical manifestation of nasal congestion, sinus pressure, post-nasal dripping, and headache. Over-expression of transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels, such as TRPA1 and TRPV1, may be involved in the pathogenesis of non-allergic rhinitis.[30]

Asthma

Neurogenic inflammation produced by neuropeptides released from sensory nerve endings to the airways is a proposed common mechanism of association between both allergic and non-allergic rhinitis with asthma. This may explain higher association of rhinitis with asthma developing later in life.[31] Environmental irritants acts as modulators of airway inflammation in these contiguous airways. Development of occupational asthma is often preceded by occupational rhinitis. Among the causative agents are flours, enzymes used in processing food, latex, isocyanates, welding fumes, epoxy resins, and formaldehyde. Accordingly, prognosis of occupational asthma is contingent on early diagnosis and the adoption of protective measures for rhinitis.[32]

Diagnosis

The different forms of rhinitis are essentially diagnosed clinically. Vasomotor rhinitis is differentiated from viral and bacterial infections by the lack of purulent exudate and crusting. It can be differentiated from allergic rhinitis because of the absence of an identifiable allergen.[33]

Prevention

In the case of infectious rhinitis, vaccination against influenza viruses, adenoviruses, measles, rubella, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, diphtheria, Bacillus anthracis, and Bordetella pertussis may help prevent it.

Management

The management of rhinitis depends on the underlying cause.

For allergic rhinitis, intranasal corticosteroids are recommended.[34] For severe symptoms intranasal antihistamines may be added.[34]

The antihistamine azelastine, applied as a nasal spray, may be effective for vasomotor rhinitis.[35] Fluticasone propionate or budesonide (both are steroids) in nostril spray form may also be used for symptomatic treatment. The antihistamine cyproheptadine is also effective, probably due to its antiserotonergic effects. A review on non-allergic rhinitis reports improvement of overall function after treatment with capsaicin (the active component of chili peppers). The quality of evidence is low, however.[36]

Pronunciation and etymology

Rhinitis is pronounced /raɪˈnaɪtɪs/,[37] while coryza is pronounced /kəˈraɪzə/.[38]

Rhinitis comes from the Ancient Greek ῥίς rhis, gen.: ῥινός rhinos "nose". Coryza has a dubious etymology. Robert Beekes rejected an Indo-European derivation and suggested a Pre-Greek reconstruction *karutya.[39] According to physician Andrew Wylie, "we use the term [coryza] for a cold in the head, but the two are really synonymous. The ancient Romans advised their patients to clean their nostrils and thereby sharpen their wits."[40]

Other animals

References

- ↑ "Rhinitis". fpnotebook.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ↑ "rhinitis | Definition, meaning & more | Collins Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ↑ "coryza | Definition, meaning & more | Collins Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Murr, Andrew H. (2020). "398. Approach to the patient with nose, sinus and ear disorders". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 2548–2556. ISBN 978-0-323-53266-2. Archived from the original on 2022-05-27. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Rhinitis - Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kaliner, Michael A (2009-06-15). "Classification of Nonallergic Rhinitis Syndromes With a Focus on Vasomotor Rhinitis, Proposed to be Known henceforth as Nonallergic Rhinopathy". The World Allergy Organization Journal. 2 (6): 98–101. doi:10.1097/WOX.0b013e3181a9d55b. ISSN 1939-4551. PMC 3650985. PMID 24229372.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tran, NP; Vickery, J; Blaiss, MS (July 2011). "Management of rhinitis: allergic and non-allergic". Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 3 (3): 148–56. doi:10.4168/aair.2011.3.3.148. PMID 21738880.

- 1 2 White, Veronica; Ruperelia, Prina (2020). "28. Respiratory disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 945. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5.

- 1 2 3 Quillen, DM; Feller, DB (1 May 2006). "Diagnosing rhinitis: allergic vs. nonallergic". American family physician. 73 (9): 1583–90. PMID 16719251.

- ↑ (Middleton's Allergy Principles and Practice, seventh edition.)

- ↑ Troullos E, Baird L, Jayawardena S (June 2014). "Common cold symptoms in children: results of an Internet-based surveillance program". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 16 (6): e144. doi:10.2196/jmir.2868. PMC 4090373. PMID 24945090.

- ↑ Brooks P (2012-10-25). The Daily Telegraph: Complete Guide to Allergies. ISBN 9781472103949. Archived from the original on 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ Valet RS, Fahrenholz JM (2009). "Allergic rhinitis: update on diagnosis". Consultant. 49: 610–613. Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ Rondón C, Canto G, Blanca M (February 2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: a new entity, characterization and further studies". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e328334f5fb. PMID 20010094. S2CID 3472235.

- ↑ Rondón C, Fernandez J, Canto G, Blanca M (2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: concept, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic approach". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 20 (5): 364–71, quiz 2 p following 371. PMID 20945601.

- ↑ Brown KR, Bernstein JA (June 2015). "Clinically relevant outcome measures of novel pharmacotherapy for nonallergic rhinitis". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 15 (3): 204–12. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000166. PMID 25899692. S2CID 22343815.

- ↑ Van Gerven L, Boeckxstaens G, Hellings P (September 2012). "Up-date on neuro-immune mechanisms involved in allergic and non-allergic rhinitis". Rhinology. 50 (3): 227–35. doi:10.4193/Rhino11.152. PMID 22888478.

- ↑ Silvers WS, Poole JA (February 2006). "Exercise-induced rhinitis: a common disorder that adversely affects allergic and nonallergic athletes". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 96 (2): 334–40. doi:10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61244-6. PMID 16498856.

- ↑ Wheeler, P. W.; Wheeler, S. F. (Sep 2005). "Vasomotor rhinitis". Am Fam Physician. 72 (6): 1057–62. PMID 16190503. Archived from the original on 2021-06-15. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- ↑ "Vasomotor rhinitis Medline Plus". Nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-04-17. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ Adelman D (2002). Manual of Allergy and Immunology: Diagnosis and Therapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 66. ISBN 9780781730525.

- ↑ "What causes non-allergic rhinitis?". NHS. Gov.uk. 2018-09-07. Archived from the original on 2018-12-19. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ↑ Hellings PW, Klimek L, Cingi C, Agache I, Akdis C, Bachert C, Bousquet J, Demoly P, Gevaert P, Hox V, Hupin C, Kalogjera L, Manole F, Mösges R, Mullol J, Muluk NB, Muraro A, Papadopoulos N, Pawankar R, Rondon C, Rundenko M, Seys SF, Toskala E, Van Gerven L, Zhang L, Zhang N, Fokkens WJ (November 2017). "Non-allergic rhinitis: Position paper of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology". Allergy. 72 (11): 1657–1665. doi:10.1111/all.13200. PMID 28474799.

- 1 2 Wheeler PW, Wheeler SF (September 2005). "Vasomotor rhinitis". American Family Physician. 72 (6): 1057–62. PMID 16190503.

- 1 2 Adams KE, Rans TS (December 2013). "Adverse reactions to alcohol and alcoholic beverages". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 111 (6): 439–45. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.016. PMID 24267355.

- ↑ Rajan JP, Wineinger NE, Stevenson DD, White AA (March 2015). "Prevalence of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease among asthmatic patients: A meta-analysis of the literature". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (3): 676–81.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.020. PMID 25282015.

- ↑ Choi JH, Kim MA, Park HS (February 2014). "An update on the pathogenesis of the upper airways in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 14 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1097/aci.0000000000000021. PMID 24300420. S2CID 205433452.

- ↑ Ramey JT, Bailen E, Lockey RF (2006). "Rhinitis medicamentosa" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 16 (3): 148–55. PMID 16784007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-10. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- 1 2 3 Bernstein JA, Singh U (April 2015). "Neural Abnormalities in Nonallergic Rhinitis". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 15 (4): 18. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0511-7. PMID 26130469. S2CID 22195726.

- ↑ Millqvist E (April 2015). "TRP channels and temperature in airway disease-clinical significance". Temperature. 2 (2): 172–7. doi:10.1080/23328940.2015.1012979. PMC 4843868. PMID 27227021.

- ↑ Eriksson J, Bjerg A, Lötvall J, Wennergren G, Rönmark E, Torén K, Lundbäck B (November 2011). "Rhinitis phenotypes correlate with different symptom presentation and risk factor patterns of asthma". Respiratory Medicine. 105 (11): 1611–21. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.06.004. PMID 21764573.

- ↑ Scherer Hofmeier K, Bircher A, Tamm M, Miedinger D (April 2012). "[Occupational rhinitis and asthma]". Therapeutische Umschau. 69 (4): 261–7. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000283. PMID 22477666.

- ↑ "Nonallergic Rhinitis - Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- 1 2 Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy JM, Lang DM (December 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis: Synopsis of Guidance From the 2017 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (12): 876–881. doi:10.7326/M17-2203. PMID 29181536.

- ↑ Bernstein JA (October 2007). "Azelastine hydrochloride: a review of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy and tolerability". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 23 (10): 2441–52. doi:10.1185/030079907X226302. PMID 17723160. S2CID 25827650.

- ↑ Gevorgyan A, Segboer C, Gorissen R, van Drunen CM, Fokkens W (July 2015). "Capsaicin for non-allergic rhinitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD010591. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010591.pub2. PMID 26171907.

- ↑ "rhinitis | Definition, meaning & more | Collins Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ↑ "coryza | Definition, meaning & more | Collins Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ↑ Beekes RS (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Brill. p. 756.

- ↑ Wylie A (1927). "Rhinology and laryngology in literature and Folk-Lore". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 42 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100029959.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Sinus Infection And Allergic Rhinitis Archived 2020-11-09 at the Wayback Machine