Neurofibromatosis type I

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | |

|---|---|

Other names:

| |

| |

| Café au lait spot characteristic of NF1 | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery, dermatology |

| Usual onset | At birth |

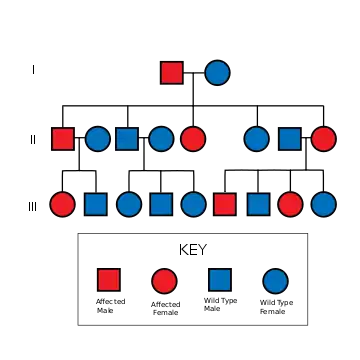

Neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1) is a complex multi-system human disorder caused by the mutation of neurofibromin, a gene on chromosome 17 that is responsible for production of a protein which is needed for normal function in many human cell types. NF-1 causes tumors along the nervous system which can grow anywhere on the body. NF-1 is one of the most common genetic disorders and is not limited to any person's race or sex. NF-1 is an autosomal dominant disorder, which means that mutation or deletion of one copy (or allele) of the NF-1 gene is sufficient for the development of NF-1, although presentation varies widely and is often different even between relatives affected by NF-1.[1]

As of 2015, there are at least 100,000 people in the U.S. and about 10,000 people in the UK who have been diagnosed with NF. Common symptoms of NF-1 include brownish-red spots in the colored part of the eye called Lisch nodules, benign skin tumors called neurofibromas, and larger benign tumors of nerves called plexiform neurofibromas, scoliosis (curvature of the spine), learning disabilities, vision disorders, mental disabilities, multiple café au lait spots and epilepsy. NF-1 affected individuals also have a much higher rate of cancer and cardiovascular disease than the population in general.

NF-1 is a developmental syndrome caused by germline mutations in neurofibromin, a gene that is involved in the RAS pathway (RASopathy). Due to its rarity and to the fact that genetic diagnosis has been used only in recent years, in the past NF-1 was in some cases confused with Legius syndrome, another syndrome with vaguely similar symptoms, including cafe-au-lait spots.[2]

NF-1 is an age specific disease; most signs of NF-1 are visible after birth (during infancy), but many symptoms of NF-1 occur as the person ages and has hormonal changes. NF-1 was formerly known as von Recklinghausen disease, after the researcher (Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen) who first documented the disorder.[3]

The severity of NF-1 varies widely, and little is known about what causes a person to have a more severe or less severe case. Even within the same family (as there is a 50% chance that a parent will pass their condition to their offspring), levels of severity can vary enormously.[1] However, 60% of people with NF-1 have mild cases, with few symptoms that have very little effect in their day-to-day lives. 20% of NF-1 patients have moderate cases, with several symptoms that have little more than cosmetic effects. The other 20% have severe cases with several symptoms that affect the person's quality of life. Even in this last group, symptoms are rarely life-threatening.[4]

Signs and symptoms

.png.webp)

The following is a list of conditions and complications associated with NF-1, and, where available, age range of onset and progressive development, occurrence percentage of NF-1 population, method of earliest diagnosis, and treatments and related medical specialties.[5][6] The progression of the condition is roughly as follows:

- Congenital musculoskeletal disorders may or may not be present

- Cutaneous conditions may be observed in early infancy

- Small tumors may arise in the retina which can eventually lead to blindness. Also, Lisch Nodules may grow on the iris, but these are harmless.

- Learning disabilities may arise in preschool children

- Neurofibromas may occur and can sometimes cause many dependent neurological conditions and cutaneous and skeletal disfigurement.

- Depression and social anxiety may occur as a result of disabilities caused by the condition

- Neurofibromas may, in 8-13% of cases, transition into cancer, which can be fatal [7]

The NF Clinical Program at St. Louis Children's Hospital Archived 2022-01-24 at the Wayback Machine maintains a comprehensive list of current NF research studies Archived 2015-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.

Musculoskeletal disorder

Musculoskeletal abnormalities affecting the skull include sphenoid bone dysplasia, congenital hydrocephalus and associated neurologic impairment. These abnormalities are non-progressive and may be diagnosed in the fetus or at birth.

Disorders affecting the spine include:

- In NF-1, there can be a generalized abnormality of the soft tissues in the fetus, which is referred to as mesodermal dysplasia, resulting in maldevelopment of skeletal structures.

- Meningoceles and formation of cystic diverticula of the dura of the spine, unrelated to Spina bifida

- Radiographically, dural ectasia can lead to scalloping of the posterior vertebral bodies and to the formation of cystic diverticula of the dura of the spine. This may result in temporary or permanent loss of lower extremity sensorimotor function.[8]

- Focal scoliosis and/or kyphosis are the most common skeletal manifestation of NF-1, occurring in 20% of affected patients. Approximately 25% of patients will require corrective surgery.

Skeletal muscle weakness and motor control deficits

Deficits in motor function in NF-1 have been long recognised and have been historically attributed to nerve dysfunction. In recent years however, studies suggest NF-1 is associated with a primary problem in muscle function (myopathy).[9]

Clinical findings in people with NF-1 include:

- Reduced skeletal muscle size

- Reduced exercise capacity

- Muscle weakness (The most recent study reports between 30–50% reduced upper and lower limb muscle strength in NF-1 children compare with matched controls[10]).

Studies in genetically modified mice have thus far confirmed that the NF1 gene is vital for normal muscle development and metabolism. Knockout of the NF1 gene in muscle results in deregulated lipid metabolism and muscle weakness.[9][11]

NF-1 is a disease in the RASopathy family of diseases, which include Costello Syndrome, Noonan Syndrome, and Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. The RASopathies also present with skeletal muscle weakness.[12] It is likely that impaired muscle function in these disorders is linked to altered Ras/MAPK signalling, however, the precise molecular mechanisms remain unknown.[9]

Facial bones and limbs

- Bowing of a long bone with a tendency to fracture and not heal, yielding a pseudarthrosis. The most common bone to be affected is the tibia, causing congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia or CPT. CPT occurs in 2–4% of individuals with NF-1. Treatment includes limb amputation or correction by Ilizarov method as a limb-sparing technique.

- Malformation of the facial bones or of the eye sockets (lambdoid suture defects, sphenoid dysplasia)

- Unilateral overgrowth of a limb. When a plexiform neurofibroma manifests on a leg or arm, it will cause extra blood circulation, and may thus accelerate the growth of the limb. This may cause considerable difference in length between left and right limbs. To equalize the difference during childhood, there is an orthopedic surgery called epiphysiodesis, where growth at the epiphyseal (growth) plate is halted. It can be performed on one side of the bone to help correct an angular deformity, or on both sides to stop growth of that bone completely. The surgery must also be carefully planned with regard to timing, as it is non-reversible. The goal is that the limbs are at near-equal length at end of growth...

Skin

- Flat pigmented lesions of the skin called café au lait spots, are hyper pigmented lesions that may vary in color from light brown to dark brown; this is reflected by the name of the condition, which means "coffee with milk". The borders may be smooth or irregular. These spots can grow from birth and can continue to grow throughout the person's lifetime. They can increase in size and numbers during puberty and during pregnancies. They are present in about 99% patient of European origin and in about 93% patient of Indian origin.[13]

- Freckling of the axillae or inguinal regions.

- Dermal neurofibroma, manifested as single or multiple firm, rubbery bumps of varying sizes on a person's skin. Age of onset is puberty. Progressive in number and size. Not malignant. Can be treated with CO2 lasers or by removal by a plastic surgeon specialized in NF1.[14][15]

Eye disease

- Lisch nodules in the iris.

- Optic nerve gliomas along one or both optic nerves or the optic chiasm can cause bulging of the eyes, involuntary eye movement, squinting, and / or vision loss. Treatment may include surgery, radiation +/- steroids, or chemotherapy (in children).[16]

Neurobehavioral developmental disorder

The most common complication in patients with NF-1 is cognitive and learning disability. These cognitive problems have been shown to be present in approximately 90% of children and adults with NF-1 and have significant effects on their schooling and everyday life.[17] These cognitive problems have been shown to be stable into adulthood mainly in the mid 20s to early 30s and do not get worse unlike some of the other physical symptoms of NF-1.[18] The most common cognitive problems are with perception, executive functioning and attention. Disorders include:

- Approximately 42% of children with NF-1 have symptoms of autism, with 36.78% of them being severe cases, 33.33% being mild to moderate cases, and 29.89% of them having both symptoms of autism and ADHD.[19]

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has been shown to be present in approximately 40% of children with NF-1.[19]

- Speech and language delays have also been identified in approximately 68% of preschool children with NF-1.[20]

- Motor deficits are common. Motor deficits due to NF-1 are probably not cerebellar.[21]

- Spatial deficit. Lovastatin, normally used to treat hypercholesterolemia, is currently in phase one of clinical trial (NCT00352599). This drug has been shown to reverse spatial deficits in mice.[22] Simvastatin, a drug similar to lovastatin, did not show benefit on cognitive function or behaviour in two randomized controlled trials in children with NF-1.[23][24]

Nervous system disease

The primary neurologic involvement in NF-1 is of the peripheral nervous system, and secondarily of the central nervous system. Schwannomatosis is a rare condition defined by the presence of multiple benign tumors of nerves that are frequently very painful. In addition to pain, weakness is a common problem. Symptoms usually begin in young or mid-adult years.

Peripheral neuropathy

Neurofibroma

A neurofibroma is a lesion of the peripheral nervous system. Its cellular lineage is uncertain, and may derive from Schwann cells, other perineural cell lines, or fibroblasts. Neurofibromas may arise sporadically, or in association with NF-1. A neurofibroma may arise at any point along a peripheral nerve. A number of drugs have been studied to treat this condition.

Neurofibroma conditions are progressive and include:

- Plexiform neurofibroma: Often congenital. Lesions are composed of sheets of neurofibromatous tissue that may infiltrate and encase major nerves, blood vessels, and other vital structures. These lesions are difficult and sometimes impossible to routinely resect without causing any significant damage to surrounding nerves and tissue. However, early intervention may be beneficial: a 2004 study in Germany concluded "Early surgical intervention of small superficial PNFs is uncomplicated, without burden for even the youngsters and enables total resection of the tumors. It may be considered as a preventive strategy for later disfigurement and functional deficits."[25][26]

- Solitary neurofibroma, affecting 8–12% of patients with NF-1. This occurs in a deep nerve trunk. Diagnosis by cross-sectional imaging (e.g., computed tomography or magnetic resonance) as a fusiform enlargement of a nerve.

- Schwannomas, peripheral nerve-sheath tumors which are seen with increased frequency in NF-1. The major distinction between a schwannoma and a solitary neurofibroma is that a schwannoma can be resected while sparing the underlying nerve, whereas resection of a neurofibroma requires the sacrifice of the underlying nerve.

- Nerve root neurofibroma.

- Bones, especially the ribs, can develop chronic erosions (pits) from the constant pressure of adjacent neurofibroma or Schwannoma. Similarly, the neural foramen of the spine can be widened due to the presence of a nerve root neurofibroma or schwannoma. Surgery may be needed when NF-1 related tumors compress organs or other structures.

Nerve sheath tumor

- Chronic pain, numbness, and/or paralysis due to peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

Other complications

- Renal artery anomalies or pheochromocytoma and associated chronic hypertension

- Schwannoma

- Plexiform fibromas

- Optic nerve glioma

- Epilepsy

Central nervous system disease

Epilepsy

- Occurrence. Epileptic seizures have been reported in up to 7% of NF-1 patients.[27]

- Diagnosis. Electroencephalograph, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomographic scan, single-photon emission CT and positron emission tomographic scan.

- Etiology. Due to cerebral tumors, cortical malformation, mesial temporal sclerosis.

- Therapy. Drug therapy (57% amenable) where not resistant (29%).

Glial tumors

Intracranially, NF-1 patients have a predisposition to develop glial tumors of the central nervous system, primarily:

- Optic nerve gliomas and associated blindness.[28]

- Astrocytoma

Focally degenerative myelin

Another CNS manifestation of NF-1 is the so-called "unidentified bright object" or UBO, which is a lesion which has increased signal on a T2 weighted sequence of a magnetic resonance imaging examination of the brain. These UBOs are typically found in the Cerebral peduncle, pons, midbrain, globus pallidus, thalamus, and optic radiations. Their exact identity remains a bit of a mystery since they disappear over time (usually, by age 16), and they are not typically biopsied or resected. They may represent a focally degenerative bit of myelin.

Dural ectasia

Within the CNS, NF-1 manifests as a weakness of the dura, which is the tough covering of the brain and spine. Weakness of the dura leads to focal enlargement due to chronic exposure to the pressures of CSF pulsation, and typically presents as paraesthesia or loss of motor or sensory function.[8] It has been shown that dural ectasia occur near plexiform neurofibromas which may be infiltrative leading to weakening of the dura.[29]

Acetazolamide has shown promise as a treatment for this condition, and in very few cases do dural ectasia require surgery.[29]

Mental disorder

Children and adults with NF-1 can experience social problems, attention problems, social anxiety, depression, withdrawal, thought problems, somatic complaints, learning disabilities and aggressive behavior.[30] Treatments include psychotherapy, antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Puberty and height

Children diagnosed with NF-1 may experience delayed or precocious puberty. Recent studies have correlated precocious puberty in individuals with NF-1 with the presence of optic pathway tumors.[31] Furthermore, the heights of children affected by NF-1 have been shown to increase normally until puberty, after which increases in height lessen when compared to healthy counterparts.[31] This eventually causes a shorter stature than expected in individuals with NF-1.

Cancer

Cancer can arise in the form of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor resulting from malignant degeneration of a plexiform neurofibroma.[26][32]

- Frequency. A plexiform neurofibroma has a lifetime risk of 8–12% of transformation into a malignant tumor.

- Diagnosis. MRI.

- Treatment. Surgery (primary), radiation therapy.

- Mortality. Malignant nerve sheath tumor was the main cause of death (60%) in a study of 1895 patients with NF-1 from France in the time period 1980–2006 indicated excess mortality in NF-1 patients compared to the general population.[33] The cause of death was available for 58 (86.6%) patients. The study found excess mortality occurred among patients aged 10 to 40 years. Significant excess mortality was found in both males and females.

Cause

Neurofibromin 1 gene

NF-1 is a microdeletion syndrome caused by a mutation of a gene located on chromosomal segment 17q11.2 on the long arm of chromosome 17 which encodes a protein known as neurofibromin[34] (not to be confused with the disorder itself) which plays a role in cell signaling.[35][36] The Neurofibromin 1 gene is a negative regulator of the Ras oncogene signal transduction pathway. It stimulates the GTPase activity of Ras. It shows greater affinity for RAS p21 protein activator 1, but lower specific activity. The mRNA for this gene is subject to RNA editing (CGA->UGA->Arg1306Term) resulting in premature translation termination. Alternatively spliced transcript variants encoding different isoforms have also been described for this gene.

In 1989, through linkage and cross over analyses, neurofibromin was localized to chromosome 17.[37] It was localized to the long arm of chromosome 17 by chance when researchers discovered chromosome exchanges between chromosome 17 with chromosome 1 and 22.[37] This exchange of genetic material presumably caused a mutation in the neurofibromin gene, leading to the NF1 phenotype. Two recurrent microdeletion types with microdeletion breakpoints located in paralogous regions flanking NF1 (proximal NF1-REP-a and distal NF1-REP-c for the 1.4 Mb type-1 microdeletion, and SUZ12 and SUZ12P for the 1.2 Mb type-2 microdeletion), are found in most cases.[38]

Structure

The neurofibromin gene was soon sequenced and found to be 350,000 base pairs in length.[39] However, the protein is 2818 amino acids long leading to the concept of splice variants.[40] For example, exon 9a, 23a and 48a are expressed in the neurons of the forebrain, muscle tissues and adult neurons respectively.[40]

Homology studies have shown that neurofibromin is 30% similar to proteins in the GTPase activating protein (GAP) family.[39] This homologous sequence is in the central portion of neurofibromin and being similar to the GAP family is recognized as a negative regulator of the Ras kinase.[41]

Additionally, being such a large protein, more active domains of the protein have been identified. One such domain interacts with the protein adenylyl cyclase,[42] and a second with collapsin response mediator protein.[43] Together, likely with domains yet to be discovered, neurofibromin regulates many of the pathways responsible for overactive cell proliferation, learning impairments, skeletal defects and plays a role in neuronal development.[44]

Inheritance and spontaneous mutation

The mutant gene is transmitted with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, but up to 50% of NF-1 cases arise due to spontaneous mutation. The incidence of NF-1 is about 1 in 3500 live births.[45]

Related medical conditions

Mutations in the NF1 gene have been linked to NF-1, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Watson syndrome. A condition with a separate gene mutation but similar Café au lait spots is Legius syndrome, which has a mutation on the SPRED1 gene.

Diagnosis

Prenatal testing and prenatal expectations

Prenatal testing may be used to identify the existence of NF-1 in the fetus. For embryos produced via in vitro fertilisation, it is possible via preimplantation genetic diagnosis to screen for NF-1.[46]

Chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis can be used to detect NF-1 in the fetus.

While the presence of NF-1 can be identified through prenatal testing the severity with which the condition will be expressed is impossible to determine.[47]

People with NF-1 have a 50% percent chance of passing the disorder on to their kids, but people can have a child born with NF-1 when they themselves do not have it. This is caused in a spontaneous change in the genes during pregnancy.

Post-natal testing

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has created specific criteria for the diagnosis of NF-1. Two of these seven "Cardinal Clinical Features" are required for positive diagnosis.[48][49] There is practical flowchart to distinguish between NF1, NF2 and schwannomatosis.[50]

- Six or more café-au-lait spots over 5 mm in greatest diameter in pre-pubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in post-pubertal individuals. Note that multiple café-au-lait spots alone are not a definitive diagnosis of NF-1 as these spots can be caused by a number of other conditions.

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or 1 plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary (Crowe sign) or inguinal regions

- Optic nerve glioma

- Two or more Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas)

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia, or thinning of the long bone cortex with or without pseudarthrosis.

- A first degree relative (parent, sibling, or offspring) with NF-1 by the above criteria.

Treatment

Selumetinib, sold under the brand name Koselugo, is a drug approved by FDA in April 2020[51] for the treatment of NF-1 in pediatric population who are two or more years of age. It is a kinase inhibitor and is indicated for use pediatric patients who are symptomatic and have plexiform neurofibromas which cannot be operated.[52]

There is no cure for the disorder itself. Instead, people with neurofibromatosis are followed by a team of specialists to manage symptoms or complications. In progress and recently concluded medical studies on NF-1 can be found by searching the official website of the National Institutes of Health.

Prognosis

NF-1 is a progressive and diverse condition, making the prognosis difficult to predict. The NF-1 gene mutations manifest the disorder differently even amongst people of the same family. This phenomenon is called variable expressivity. For example, some individuals have no symptoms, while others may have a manifestation that is rapidly more progressive and severe.

For many NF-1 patients, a primary concern is the disfigurement caused by cutaneous/dermal neurofibromas, pigmented lesions, and the occasional limb abnormalities. However, there are many more severe complications caused by NF-1 like increased cancer risk, a plexiform neurofibroma has a 10-15% chance of developing into a MPNST (Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumour) . Many NF patients live perfectly normal and uninterrupted lives.

Epidemiology

NF-1 is estimated to affect around 25,000 people in the UK.[53]

See also

References

- 1 2 Kunc, V.; Venkatramani, H. (2019). "Neurofibromatosis 1 Diagnosed in Mother Only after a Follow-up of Her Daughter". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 52 (2): 260. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1693503. PMC 6785427. PMID 31602150.

- ↑ "About Neurofibromatosis – The University of Chicago Medicine". www.uchospitals.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ Costa, R. M.; Silva, A. J. (2002). "Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the cognitive deficits associated with neurofibromatosis 1". Journal of Child Neurology. 17 (8): 622–626, discussion 626–9, 626–51. doi:10.1177/088307380201700813. PMID 12403561. S2CID 20385802.

- ↑ "NF1 | Children's Tumor Foundation". Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- ↑ ""Neurofibromatosis 1: Current Issues in Diagnosis, Therapy, and Patient Management", by David Viskochil MD PhD, Mountain States Genetic Foundation, Denver 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- ↑ ""Current Therapies for Neurofibromatosis Type 1", by Laura Klesse MD PhD, Mountain States Genetic Foundation, Denver 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ↑ D, Evans (April 1, 2003). "Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis 1". Journal of Medical Genetics. 39 (5): 311–4. doi:10.1136/jmg.39.5.311. PMC 1735122. PMID 12011145.

- 1 2 Mutua, Victor; Mong’are, Newnex; Bundi, Brian; von Csefalvay, Chris; Oriko, David; Kitunguu, Peter (September 2021). "Sudden bilateral lower limb paralysis with dural ectasia in Neurofibromatosis type 1: A case report". Medicine: Case Reports and Study Protocols. 2 (9): e0165. doi:10.1097/MD9.0000000000000165. ISSN 2691-3895. Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- 1 2 3 Summers, M.A.; Quinlan, K.G.; Payne, J.M.; Little, D.G.; North, K.N.; Schindeler, A. (June 2015). "Skeletal muscle and motor deficits in Neurofibromatosis Type 1". Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 15 (2): 161–170. PMC 5133719. PMID 26032208.

- ↑ Cornett, Kayla M. D.; North, Kathryn N.; Rose, Kristy J.; Burns, Joshua (2015). "Muscle weakness in children with neurofibromatosis type 1". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 57 (8): 733–736. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12777. PMID 25913846. S2CID 38835893.

- ↑ Sullivan, Kate; El-Hoss, Jad; Quinlan, Kate G.R.; Deo, Nikita; Garton, Fleur; Seto, Jane T.C.; Gdalevitch, Marie; Turner, Nigel; Cooney, Gregory J.; Kolanczyk, Mateusz; North, Kathryn N.; Little, David G.; Schindeler, Aaron (1 March 2014). "NF1 is a critical regulator of muscle development and metabolism". Human Molecular Genetics. 23 (5): 1250–1259. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt515. PMC 3954124. PMID 24163128.

- ↑ Stevenson, David A.; Allen, Shawn; Tidyman, William E.; Carey, John C.; Viskochil, David H.; Stevens, Austin; Hanson, Heather; Sheng, Xiaoming; Thompson, Brandi A.; J. Okumura, Megumi; Reinker, Kent; Johnson, Barbara; Rauen, Katherine A. (September 2012). "Peripheral muscle weakness in RASopathies". Muscle & Nerve. 46 (3): 394–399. doi:10.1002/mus.23324. PMID 22907230. S2CID 21120799.

- ↑ Lakshmanan, Aarthi; Bubna, AdityaKumar; Sankarasubramaniam, Anandan; Veeraraghavan, Mahalakshmi; Rangarajan, Sudha; Sundaram, Murugan (2016). "A clinical study of neurofibromatosis-1 at a tertiary health care centre in south India". Pigment International. 3 (2): 102. doi:10.4103/2349-5847.196302.

- ↑ "Northwestern Health Sciences University ~ Diagnosis and Discussion". www.nwhealth.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ Piersall, Linda, David H. Gutmann, & Rosalie Ferner. Living with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Guide for Adults. New York, NY: The National Neurofibromatosis Foundation, Inc. Print.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Optic glioma

- ↑ Hyman SL, Shores A, North KN (October 2005). "The nature and frequency of cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1". Neurology. 65 (7): 1037–44. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000179303.72345.ce. PMID 16217056. S2CID 10198510.

- ↑ Hyman SL, Gill DS, Shores EA, et al. (April 2003). "Natural history of cognitive deficits and their relationship to MRI T2-hyperintensities in NF1". Neurology. 60 (7): 1139–45. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000055090.78351.C1. PMID 12682321. S2CID 26812237.

- 1 2 Garg, S.; Lehtonen, A.; Huson, S. M.; Emsley, R.; Trump, D.; Evans, D. G.; Green, J. (2013). "Autism and other psychiatric comorbidity in neurofibromatosis type 1: Evidence from a population-based study". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 55 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12043. PMID 23163236. S2CID 11781870.

- ↑ Thompson HL, Viskochil DH, Stevenson DA, Chapman KL (February 2010). "Speech-language characteristics of children with neurofibromatosis type 1". Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 152A (2): 284–90. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33235. PMID 20101681. S2CID 26650152.

- ↑ van der Vaart T, van Woerden GM, Elgersma Y, de Zeeuw CI, Schonewille M (June 2011). "Motor deficits in neurofibromatosis type 1 mice: the role of the cerebellum". Genes Brain Behav. 10 (4): 404–9. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00685.x. PMID 21352477. S2CID 19609654.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00352599 for "Trial to Evaluate the Safety of Lovastatin in Individuals With Neurofibromatosis Type I (NF1)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Krab LC, de Goede-Bolder A, Aarsen FK, et al. (July 2008). "Effect of simvastatin on cognitive functioning in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 300 (3): 287–94. doi:10.1001/jama.300.3.287. PMC 2664742. PMID 18632543.

- ↑ van der Vaart T, Plasschaert E, Rietman AB, et al. (November 2013). "Simvastatin for cognitive deficits and behavioural problems in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1-SIMCODA): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial". Lancet Neurol. 12 (11): 1076–83. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70227-8. PMID 24090588. S2CID 206161362. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- ↑ Friedrich, Reinhard (2005). "Resection of small plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 children". World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 3 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-3-6. PMC 549083. PMID 15683544.

- 1 2 Korf, BR (26 March 1999). "Plexiform neurofibromas". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 89 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990326)89:1<31::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-w. PMID 10469434.

- ↑ Vivarelli R, Grosso S, Calabrese F, et al. (May 2003). "Epilepsy in neurofibromatosis 1". J. Child Neurol. 18 (5): 338–42. doi:10.1177/08830738030180050501. PMID 12822818. S2CID 39229702.

- ↑ Listernick, R; Charrow, J; Gutmann, DH (26 March 1999). "Intracranial gliomas in neurofibromatosis type 1". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 89 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990326)89:1<38::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-m. PMID 10469435.

- 1 2 Polster, Sean P; Dougherty, Mark C; Zeineddine, Hussein A; Lyne, Seán B; Smith, Heather L; MacKenzie, Cynthia; Pytel, Peter; Yang, Carina W; Tonsgard, James H; Warnke, Peter C; Frim, David M (1 May 2020). "Dural Ectasia in Neurofibromatosis 1: Case Series, Management, and Review". Neurosurgery. 86 (5): 646–655. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyz244. PMID 31350851.

- ↑ Johnson NS, Saal HM, Lovell AM, Schorry EK (June 1999). "Social and emotional problems in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: evidence and proposed interventions". J. Pediatr. 134 (6): 767–72. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70296-9. PMID 10356149.

- 1 2 Virdis, R et al. “Growth and Pubertal Disorders in Neurofibromatosis Type 1.” Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 16 Suppl 2 (2003): 289–292. Print.

- ↑ Matsui, I; Tanimura, M; Kobayashi, N; Sawada, T; Nagahara, N; Akatsuka, J (1 November 1993). "Neurofibromatosis type 1 and childhood cancer". Cancer. 72 (9): 2746–54. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931101)72:9<2746::AID-CNCR2820720936>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 8402499.

- ↑ Duong, Tu; Sbidian, Emilie; Valeyrie-Allanore, Laurence; Vialette, Cédric; Ferkal, Salah; Hadj-Rabia, Smaïl; Glorion, Christophe; Lyonnet, Stanislas; Zerah, Michel; Kemlin, Isabelle; Rodriguez, Diana; Bastuji-Garin, Sylvie; Wolkenstein, Pierre (2011). "Mortality Associated with Neurofibromatosis 1: A Cohort Study of 1895 Patients in 1980–2006 in France". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 6: 18. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-18. PMC 3095535. PMID 21542925.

- ↑ Wallace, MR; Marchuk, DA; Andersen, LB; Letcher, R; Odeh, HM; Saulino, AM; Fountain, JW; Brereton, A; Nicholson, J; Mitchell, AL (13 July 1990). "Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients". Science. 249 (4965): 181–6. Bibcode:1990Sci...249..181W. doi:10.1126/science.2134734. PMID 2134734.

- ↑ "neurofibromin 1" Archived 2017-06-21 at the Wayback Machine GeneCards

- ↑ ""Human Gene NF1 (uc002hgf.1) Description and Page Index"". Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- 1 2 Goldberg NS, Collins FS (November 1991). "The hunt for the neurofibromatosis gene". Arch Dermatol. 127 (11): 1705–7. doi:10.1001/archderm.1991.01680100105014. PMID 1952978.

- ↑ Pasmant, E; Sabbagh, A; Spurlock, G; Laurendeau, I; Grillo, E; Hamel, MJ; Martin, L; Barbarot, S; Leheup, B; Rodriguez, D; Lacombe, D; Dollfus, H; Pasquier, L; Isidor, B; Ferkal, S; Soulier, J; Sanson, M; Dieux-Coeslier, A; Bièche, I; Parfait, B; Vidaud, M; Wolkenstein, P; Upadhyaya, M; Vidaud, D; members of the NF France, Network (June 2010). "NF1 microdeletions in neurofibromatosis type 1: from genotype to phenotype". Human Mutation. 31 (6): E1506–18. doi:10.1002/humu.21271. PMID 20513137. S2CID 24525378. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- 1 2 Marchuk DA, Saulino AM, Tavakkol R, et al. (December 1991). "cDNA cloning of the type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: complete sequence of the NF1 gene product" (PDF). Genomics. 11 (4): 931–40. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(91)90017-9. hdl:2027.42/29018. PMID 1783401. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- 1 2 Gutmann DH, Giovannini M (2002). "Mouse models of neurofibromatosis 1 and 2". Neoplasia. 4 (4): 279–90. doi:10.1038/sj.neo.7900249. PMC 1531708. PMID 12082543.

- ↑ Feldkamp MM, Angelov L, Guha A (February 1999). "Neurofibromatosis type 1 peripheral nerve tumors: aberrant activation of the Ras pathway". Surg Neurol. 51 (2): 211–8. doi:10.1016/S0090-3019(97)00356-X. PMID 10029430.

- ↑ Hannan F, Ho I, Tong JJ, Zhu Y, Nurnberg P, Zhong Y (April 2006). "Effect of neurofibromatosis type I mutations on a novel pathway for adenylyl cyclase activation requiring neurofibromin and Ras". Hum. Mol. Genet. 15 (7): 1087–98. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl023. PMC 1866217. PMID 16513807.

- ↑ Ozawa T, Araki N, Yunoue S, et al. (November 2005). "The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product neurofibromin enhances cell motility by regulating actin filament dynamics via the Rho-ROCK-LIMK2-cofilin pathway". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (47): 39524–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M503707200. PMID 16169856.

- ↑ Le LQ, Parada LF (July 2007). "Tumor microenvironment and neurofibromatosis type I: connecting the GAPs". Oncogene. 26 (32): 4609–16. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210261. PMC 2760340. PMID 17297459.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): NEUROFIBROMATOSIS, TYPE I; NF1 - 162200

- ↑ ""British couple successfully screens out genetic disorder using NHS-funded PGD" by Antony Blackburn-Starza, June 9, 2008, BioNews 461". Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ↑ "About Neurofibromatosis". Genome.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ "Neurofibromatosis: Conference Statement". Archives of Neurology. 45 (5): 575. 1 May 1988. doi:10.1001/archneur.1988.00520290115023.

- ↑ Huson, Susan Mary; Hughes, Richard Anthony Cranmer (1994). The neurofibromatoses: a pathogenetic and clinical overview. London: Chapman & Hall. 1.3.2:9. ISBN 978-0-412-38920-7.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Luiz Oswaldo Carneiro; Batista, Pollyanna Barros; Goloni-Bertollo, Eny Maria; Souza-Costa, Danielle de; Eliam, Lucas; Eliam, Miguel; Cunha, Karin Soares Gonçalves; Darrigo Junior, Luiz Guilherme; Ferraz Filho, José Roberto Lopes; Geller, Mauro; Gianordoli-Nascimento, Ingrid F.; Madeira, Luciana Gonçalves; Malloy-Diniz, Leandro Fernandes; Mendes, Hérika Martins; Miranda, Débora Marques de; Pavarino, Erika Cristina; Baptista-Pereira, Luciana; Rezende, Nilton A.; Rodrigues, Luíza de Oliveira; Silva, Carla Menezes da; Souza, Juliana Ferreira de; Souza, Márcio Leandro Ribeiro de; Stangherlin, Aline; Valadares, Eugênia Ribeiro; Vidigal, Paula Vieira Teixeira (2014). "Neurofibromatoses: part 1 – diagnosis and differential diagnosis". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 72 (3): 241–50. doi:10.1590/0004-282X20130241. PMID 24676443.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (2020-04-10). "FDA Approves First Therapy for Children with Debilitating and Disfiguring Rare Disease". FDA. Archived from the original on 2020-04-10. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- ↑ AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. Koselugo(Selumetinib)[package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213756s000lbl.pdf Archived 2021-12-27 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- ↑ Ashton, Rosemary; Crawford, Hilda; Morrison, Patrick; McKee, Shane; Huson, Susan (2012). "NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE 1 (NF1) A GUIDE FOR ADULTS AND FAMILIES" (PDF). Nerve Tumours UK. Nerve Tumours UK. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- Friedman, J. M. (1993). "Neurofibromatosis 1". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- Legius, Eric; Stevenson, David (1993). "Legius Syndrome". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10. Retrieved 2022-01-25.