Abacavir

| |

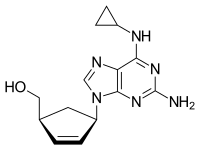

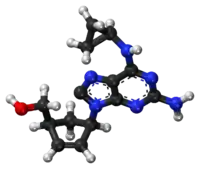

Chemical structure of abacavir | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˈbækəvɪər/ ( |

| Trade names | Ziagen, others[1] |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)[1] |

| Main uses | HIV/AIDS[2] |

| Side effects | Vomiting, trouble sleeping, fever, feeling tired[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (solution or tablets) |

| Defined daily dose | 0.6 gram[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| WHO Essential Medicines | 611 |

| MedlinePlus | a699012 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.54 ± 0.63 h |

| Excretion | Kidney (1.2% abacavir, 30% 5'-carboxylic acid metabolite, 36% 5'-glucuronide metabolite, 15% unidentified minor metabolites). Fecal (16%) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H18N6O |

| Molar mass | 286.339 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 165 °C (329 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Abacavir, sold under the brand name Ziagen, is a medication used to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.[1][4] Similar to other nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), abacavir is used together with other HIV medications, and is not recommended by itself.[5] It is taken by mouth as a tablet or solution and may be used in children over the age of three months.[1][6]

Abacavir is generally well tolerated.[6] Common side effects include vomiting, trouble sleeping, fever, and feeling tired.[1] More severe side effects include hypersensitivity, liver damage, and lactic acidosis.[1] Genetic testing can indicate whether a person is at higher risk of developing hypersensitivity.[1] Symptoms of hypersensitivity include rash, vomiting, and shortness of breath.[6] Abacavir is in the NRTI class of medications, which work by blocking reverse transcriptase, an enzyme needed for HIV virus replication.[7] Within the NRTI class, abacavir is a carbocyclic nucleoside.[1]

Abacavir was patented in 1988, and approved for use in the United States in 1998.[8][9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10] It is available as a generic medication.[1] The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2014 is between US$0.36 and US$0.83 per day.[11] As of 2016 the wholesale cost for a typical month of medication in the United States is US$70.50.[12] Commonly, abacavir is sold together with other HIV medications, such as abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine, abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine, and abacavir/lamivudine.[6][7] The combination abacavir/lamivudine is also an essential medicine.[10]

Medical uses

_300mg.jpg.webp)

Abacavir tablets and oral solution, in combination with other antiretroviral agents, are indicated for the treatment of HIV-1 and 2 infection.[2]

Abacavir should always be used in combination with other antiretroviral agents. Abacavir should not be added as a single agent when antiretroviral regimens are changed due to loss of virologic response.

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 600 mg (by mouth).[3] The dose in people over 25 kg is 300 mg twice per day by mouth while that in children under 25 kg is 8 mg/kg.[2]

Side effects

Common adverse reactions include nausea, headache, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and trouble sleeping. Rare but serious side effects include hypersensitivity reaction such as rash, elevated AST and ALT, depression, anxiety, fever/chills, URI, lactic acidosis, hypertriglyceridemia, and lipodystrophy.[13][14]

People with liver disease should be cautious about using abacavir because it can aggravate the condition. Signs of liver problems include nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, dark-colored urine, yellowing of the skin, and yellowing of the whites of the eyes. The use of nucleoside drugs such as abacavir can very rarely cause lactic acidosis. Signs of lactic acidosis include fast or irregular heartbeat, unusual muscle pain, fatigue, difficulty breathing and stomach pain with nausea and vomiting.[15] Abacavir can also lead to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, a change in body fat as well as an increased risk of heart attack.

Resistance to abacavir has developed in laboratory versions of HIV which are also resistant to other HIV-specific antiretrovirals such as lamivudine, didanosine, and zalcitabine. HIV strains that are resistant to protease inhibitors are not likely to be resistant to abacavir.

Abacavir is contraindicated for use in infants under three months of age.

Little is known about the effects of Abacavir overdose. Overdose victims should be taken to a hospital emergency room for treatment.

Hypersensitivity syndrome

Hypersensitivity to abacavir is strongly associated with a specific allele at the human leukocyte antigen B locus namely HLA-B*5701.[16][17][18] There is an association between the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 and ancestry. The prevalence of the allele is estimated to be 3.4 to 5.8 percent on average in populations of European ancestry, 17.6 percent in Indian Americans, 3.0 percent in Hispanic Americans, and 1.2 percent in Chinese Americans.[19][20] There is significant variability in the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 among African populations. In African Americans, the prevalence is estimated to be 1.0 percent on average, 0 percent in the Yoruba from Nigeria, 3.3 percent in the Luhya from Kenya, and 13.6 percent in the Masai from Kenya, although the average values are derived from highly variable frequencies within sample groups.[21]

Common symptoms of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome include fever, malaise, nausea, and diarrhea. Some patients may also develop a skin rash.[22] Symptoms of AHS typically manifest within six weeks of treatment using abacavir, although they may be confused with symptoms of HIV, immune reconstitution syndrome, hypersensitivity syndromes associated with other drugs, or infection.[23] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released an alert concerning abacavir and abacavir-containing medications on 24 July 2008,[24] and the FDA-approved drug label for abacavir recommends pre-therapy screening for the HLA-B*5701 allele and the use of alternative therapy in subjects with this allele.[25] Additionally, both the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group recommend use of an alternative therapy in individuals with the HLA-B*5701 allele.[26][27]

Skin-patch testing may also be used to determine whether an individual will experience a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir, although some patients susceptible to developing AHS may not react to the patch test.[28]

The development of suspected hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir requires immediate and permanent discontinuation of abacavir therapy in all patients, including patients who do not possess the HLA-B*5701 allele. On 1 March 2011, the FDA informed the public about an ongoing safety review of abacavir and a possible increased risk of heart attack associated with the drug.[29] A meta-analysis of 26 studies conducted by the FDA, however, did not find any association between abacavir use and heart attack [30][31]

Immunopathogenesis

The mechanism underlying abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is related to the change in the HLA-B*5701 protein product. Abacavir binds with high specificity to the HLA-B*5701 protein, changing the shape and chemistry of the antigen-binding cleft. This results in a change in immunological tolerance and the subsequent activation of abacavir-specific cytotoxic T cells, which produce a systemic reaction known as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome.[32]

Interaction

Abacavir, and in general NRTIs, do not undergo hepatic metabolism and therefore have very limited (to none) interaction with the CYP enzymes and drugs that effect these enzymes. That being said there are still few interactions that can affect the absorption or the availability of abacavir. Below are few of the common established drug and food interaction that can take place during abacavir co-administration:

- Protease inhibitors such as tipranavir or ritonovir may decrease the serum concentration of abacavir through induction of glucuronidation. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[33][34]

- Ethanol may result in increased levels of abacavir through the inhibition of alcohol dehydrogenase. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[33][35]

- Methadone may diminish the therapeutic effect of Abacavir. Abacavir may decrease the serum concentration of Methadone.[36][37]

- Orlistat may decrease the serum concentration of antiretroviral drugs. The mechanism of this interaction is not fully established but it is suspected that it is due to the decreased absorption of abacavir by orlistat.[38]

- Cabozantinib: Drugs from the MPR2 inhibitor (Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 inhibitors) family such as abacavir could increase the serum concentration of Cabozantinib.[39]

Mechanism of action

Abacavir is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor that inhibits viral replication. It is a guanosine analogue that is phosphorylated to carbovir triphosphate (CBV-TP). CBV-TP competes with the viral molecules and is incorporated into the viral DNA. Once CBV-TP is integrated into the viral DNA, transcription and HIV reverse transcriptase is inhibited.[40]

Pharmacokinetics

Abacavir is given orally and is rapidly absorbed with a high bioavailability of 83%. Solution and tablet have comparable concentrations and bioavailability. Abacavir can be taken with or without food.

Abacavir can cross the blood-brain barrier. Abacavir is metabolized primarily through the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronyl transferase to an inactive carboxylate and glucuronide metabolites. It has a half-life of approximately 1.5-2.0 hours. If a person has liver failure, abacavir's half life is increased by 58%.

Abacavir is eliminated via excretion in the urine (83%) and feces (16%). It is unclear whether abacavir can be removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.[40]

History

Robert Vince and Susan Daluge along with Mei Hua, a visiting scientist from China, developed the medication in the '80s.[41][42][43]

Abacavir was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 18 December 1998, and is thus the fifteenth approved antiretroviral drug in the United States. Its patent expired in the United States on 26 December 2009.

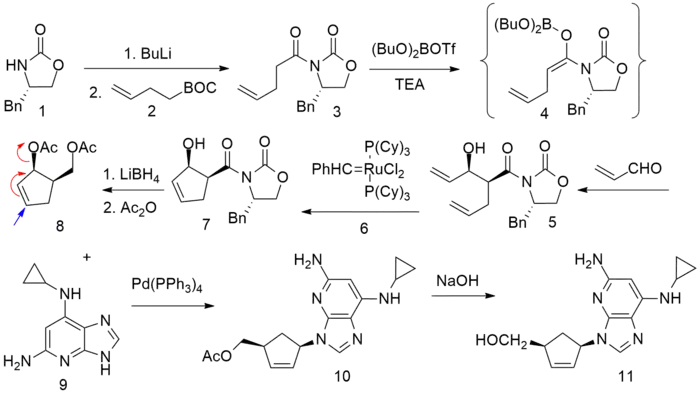

Synthesis

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Abacavir Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "ABACAVIR = ABC oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ "Drug Name Abbreviations Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ "What Not to Use Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Yuen GJ, Weller S, Pakes GE (2008). "A review of the pharmacokinetics of abacavir". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 47 (6): 351–71. doi:10.2165/00003088-200847060-00001. PMID 18479171. S2CID 31107341.

- 1 2 "Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs or 'nukes') - HIV/AIDS". www.hiv.va.gov. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 505. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Kane, Brigid M. (2008). HIV/AIDS Treatment Drugs. Infobase Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 9781438102078. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- 1 2 World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "International Drug Price Indicator Guide". ERC. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "NADAC as of 2016-12-07 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ↑ "Abacavir Adverse Reactions". Epocrates Online. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Professional Drug Facts

- ↑ "Abacavir". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, et al. (2008). "HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir". New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (6): 568–579. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0706135. PMID 18256392. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ↑ Rauch A, Nolan D, Martin A, et al. (2006). "Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (1): 99–102. doi:10.1086/504874. PMID 16758424.

- ↑ Dean L (2015). "Abacavir Therapy and HLA-B*57:01 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520363. Bookshelf ID: NBK315783. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ Hetherington S, Hughes AR, Mosteller M, et al. (2002). "Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir". Lancet. 359 (9312): 1121–1122. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08158-8. PMID 11943262.

- ↑ Mallal S, Nolan D, Witt C, et al. (2002). "Association between presence of HLA*B5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir". Lancet. 359 (9308): 727–732. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. PMID 11888582.

- ↑ Rotimi CN, Jorde LB (2010). "Ancestry and disease in the age of genomic medicine". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (16): 1551–1558. doi:10.1056/nejmra0911564. PMID 20942671.

- ↑ Phillips E, Mallal S (2009). "Successful translation of pharmacogenetics into the clinic: the abacavir example". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 13 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/bf03256308. ISSN 1177-1062. PMID 19351209.

- ↑ Phillips E, Mallal S (2007). "Drug hypersensitivity in HIV". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 7 (4): 324–330. doi:10.1097/aci.0b013e32825ea68a. PMID 17620824.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Abacavir (marketed as Ziagen) and Abacavir-Containing Medications". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Ziagen- abacavir sulfate tablet, film coated label". DailyMed. 30 September 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ↑ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A, et al. (May 2011). "Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte--an update of guidelines". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 89 (5): 662–73. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232.

- ↑ Martin MA, Hoffman JM, Freimuth RR, et al. (May 2014). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for HLA-B Genotype and Abacavir Dosing: 2014 update". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 95 (5): 499–500. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.38. PMC 3994233. PMID 24561393.

- ↑ Shear NH, Milpied B, Bruynzeel DP, et al. (2008). "A review of drug patch testing and implications for HIV clinicians". AIDS. 22 (9): 999–1007. doi:10.1097/qad.0b013e3282f7cb60. PMID 18520343.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review update of Abacavir and possible increased risk of heart attack". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ↑ "FDA Alert: Abacavir - Ongoing Safety Review: Possible Increased Risk of Heart Attack". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C, et al. (December 2012). "No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 61 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c. PMID 22932321. S2CID 7997822.

- ↑ Illing PT, Vivian JP, Dudek NL, et al. (2012). "Immune self-reactivity triggered by drug-modified HLA-peptide repertoire". Nature. 486 (7404): 554–8. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..554I. doi:10.1038/nature11147. PMID 22722860. S2CID 4408811.

- 1 2 Prescribing information. Ziagen (abacavir). Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, July 2002

- ↑ Vourvahis M, Kashuba AD (2007). "Mechanisms of Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug Interactions Associated with Ritonavir-Enhanced Tipranavir". Pharmacotherapy. 27 (6): 888–909. doi:10.1592/phco.27.6.888. PMID 17542771.

- ↑ McDowell JA, Chittick GE, Stevens CP, et al. (2000). "", "Pharmacokinetic Interaction of Abacavir (1592U89) and Ethanol in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Adults". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 44 (6): 1686–90. doi:10.1128/aac.44.6.1686-1690.2000. PMC 89933. PMID 10817729.

- ↑ Berenguer J, Pérez-Elías MJ, Bellón JM, et al. (2006). "Effectiveness and safety of abacavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine in antiretroviral therapy-naive HIV-infected patients: results from a large multicenter observational cohort". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 41 (2): 154–159. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000194231.08207.8a. PMID 16394846. S2CID 17609676.

- ↑ Dolophine(methadone) [prescribing information]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories, Inc.; March 2015.

- ↑ Gervasoni C, Cattaneo D, Di Cristo V, et al. (2016). "Orlistat: weight lost at cost of HIV rebound". J Antimicrob Chemother. 71 (6): 1739–1741. doi:10.1093/jac/dkw033. PMID 26945709.

- ↑ Cometriq (cabozantinib) [prescribing information]. South San Francisco, CA: Exelixis, Inc.; May 2016.

- 1 2 Product Information: ZIAGEN(R) oral tablets, oral solution, abacavir sulfate oral tablets, oral solution. ViiV Healthcare (per Manufacturer), Research Triangle Park, NC, 2015.

- ↑ "Dr. Robert Vince - 2010 Inductee". Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ "Robert Vince, PhD (faculty listing)". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Daluge SM, Good SS, Faletto MB, et al. (May 1997). "1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 41 (5): 1082–1093. doi:10.1128/AAC.41.5.1082. PMC 163855. PMID 9145874.

- ↑ Crimmins MT, King BW (1996). "An Efficient Asymmetric Approach to Carbocyclic Nucleosides: Asymmetric Synthesis of 1592U89, a Potent Inhibitor of HIV Reverse Transcriptase". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 61 (13): 4192–4193. doi:10.1021/jo960708p. PMID 11667311.

Further reading

- Dean L (April 2018). "Abacavir Therapy and HLA-B*57:01 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520363. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

External links

- "Abacavir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Abacavir pathway on PharmGKB Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) Archived 8 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

| Identifiers: |

|---|