Didanosine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | dye dan' oh seen[1] |

| Trade names | Videx |

| Other names | 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 400 mg OD[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691006 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 30 to 54% |

| Protein binding | Less than 5% |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

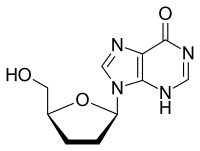

| Formula | C10H12N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 236.231 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Didanosine (ddI), sold under the brand name Videx, is a medication used to treat HIV/AIDS.[2] It is taken with other HIV medication.[2] It is not a first line treatment.[3] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include diarrhea, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, headache, and rash.[1] Other side effects may include pancreatitis, liver problems, lactic acidosis, and optic neuritis.[1] Other medications are generally preferred in pregnancy.[3] It is a nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI).[2]

Didanosine was first described in 1975 and approved for use in the United States in 1991.[4] In the United States 30 tablets of 400 mg costs about 270 USD as of 2021.[5] While previously commonly used, it is now rarely used due to better tolerated medicine.[6]

Medical uses

Resistance

Drug resistance to didanosine does develop, though slower than to zidovudine (ZDV). The most common mutation observed in vivo is L74V in the viral pol gene, which confers cross-resistance to zalcitabine; other mutations observed include K65R and M184V .[7][8]

Dosage

In adults a dose of 400 mg per day is used.[1]

Side effects

The most common side effects are diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, headache, and rash.[9] Peripheral neuropathy occurred in 21-26% of participants in key didanosine trials.[7]

Pancreatitis is rarely observed but has caused occasional fatalities, and has black box warning status.[10] Other reported serious adverse events are retinal changes, optic neuritis and alterations of liver functions. The risk of some of these serious adverse events is increased by drinking alcohol.

In 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration stated there is a risk for a rare but potentially fatal liver disorder, non-cirrhotic portal hypertension.[11]

Interactions

- A significant interaction has also been recorded with allopurinol, and administration of these drugs together should be avoided.[7]

- Reduction in indinavir and delavirdine plasma levels have been shown to occur when administered simultaneously with didanosine; these drugs should be administered at different times.[7]

- Ketoconazole, itraconazole, ciprofloxacin should be administered at a different time from didanosine due to interactions with the buffering agent.[7]

- Administration with drugs with overlapping toxicity, such as zalcitabine and stavudine, is not recommended.[12]

- Alcohol can exacerbate didanosine's toxicity, and avoiding drinking alcohol while taking didanosine is recommended.[7]

Mechanism of action

Didanosine (ddI) is a nucleoside analogue of adenosine.[13] It differs from other nucleoside analogues, because it does not have any of the regular bases, instead it has hypoxanthine attached to the sugar ring. Within the cell, ddI is phosphorylated to the active metabolite of dideoxyadenosine triphosphate, ddATP, by cellular enzymes. Like other anti-HIV nucleoside analogs, it acts as a chain terminator by incorporation and inhibits viral reverse transcriptase by competing with natural dATP.

Pharmacokinetics

Oral absorption of didanosine is fairly low (42%)[7] but rapid. Food substantially reduces didanosine bioavailability, and the drug should be administered on an empty stomach.[7] The half-life in plasma is only 1.5 hours,[7] but in the intracellular environment more than 12 hours. An enteric-coated formulation is now marketed as well. Elimination is predominantly renal; the kidneys actively secrete didanosine, the amount being 20% of the oral dose.

History

The related pro-drug of didanosine, 2′,3′-dideoxyadenosine (ddA), was initially synthesized by Morris J. Robins (professor of Organic Chemistry at Brigham Young University) and R.K. Robins in 1964. Subsequently, Samuel Broder, Hiroaki Mitsuya, and Robert Yarchoan in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) found that ddA and ddI could inhibit HIV replication in the test tube and conducted initial clinical trials showing that didanosine had activity in patients infected with HIV. On behalf of the NCI, they were awarded patents on these activities. Since the NCI does not market products directly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded a ten-year exclusive license to Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (BMS) to market and sell ddI as Videx tablets.

Didanosine became the second drug approved for the treatment of HIV infection in many other countries, including in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on October 9, 1991. Its FDA approval helped bring down the price of zidovudine (ZDV), the initial anti-HIV drug. [Source needed on pricing effect.]

Didanosine has weak acid stability and is easily damaged by stomach acid. Therefore, the original formula approved by the FDA used chewable tablets that included an antacid buffering compound to neutralize stomach acid. The chewable tablets were not only large and fragile, they also were foul-tasting and the buffering compound would cause diarrhea. Although the FDA had not approved the original formulation for once-a-day dosing it was possible for some people to take it that way.

At the end of its ten-year license, BMS re-formulated Videx as Videx EC and patented that, which reformulation the FDA approved in 2000. The new formulation is a smaller capsule containing coated microspheres instead of using a buffering compound. It is approved by the FDA for once-a-day dosing. Also at the end of that ten-year period, the NIH licensed didanosine to Barr Laboratories under a non-exclusive license, and didanosine became the first generic anti-HIV drug marketed in the United States.

One of the patents for ddI expired in the United States on August 29, 2006, but other patents extend beyond that time.

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 "DailyMed - DIDANOSINE capsule, delayed release pellets". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Didanosine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Didanosine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 505. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-02-07. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ "Didanosine Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Didanosine". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "VIDEX (didanosine): chewable/dispersible buffered tablets; buffered powder for oral solution; pediatric powder for oral solution". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. July 2000. Archived from the original on 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ Moyle GJ (August 1996). "Use of viral resistance patterns to antiretroviral drugs in optimising selection of drug combinations and sequences". Drugs. 52 (2): 168–85. doi:10.2165/00003495-199652020-00002. PMID 8841736. S2CID 27709969.

- ↑ "Didanosine Side Effects in Detail - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ↑ "Didanosine Videx - Treatment - National HIV Curriculum". www.hiv.uw.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ↑ "Serious liver disorder associated with the use of Videx/Videx EC (didanosine)". FDA Drug Safety Communication. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 19 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ DHHS Panel (May 4, 2006). "Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents". AIDSInfo. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2006-05-06.

- ↑ Pruvost A, Negredo E, Benech H, Theodoro F, Puig J, Grau E, et al. (May 2005). "Measurement of intracellular didanosine and tenofovir phosphorylated metabolites and possible interaction of the two drugs in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 49 (5): 1907–14. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.5.1907-1914.2005. PMC 1087635. PMID 15855513.

Further reading

- "NIH Oral History of Samuel Broder describing development of AIDS drugs". Office of NIH History. February 2, 1997. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "NIH Oral History of Robert Yarchoan describing development of AIDS drugs". Office of NIH History. April 3, 1998. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "Report on Development and Licensing of ddI" (PDF). National Institutes of Health Office of Technology Transfer. September 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-30.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|