Origin of COVID-19

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

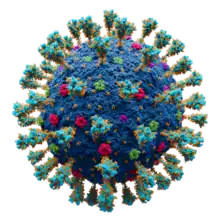

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

|

|

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been efforts by scientists, governments, and others to determine the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Most scientists agree that, as with many other pandemics in human history,[1][2][3] the virus is likely derived from a bat-borne virus transmitted to humans via another animal in nature or during wildlife trade such as that in food markets.[11] Many other explanations, including several conspiracy theories, have been proposed.[12][13][14] Some scientists and politicians have speculated that SARS-CoV-2 was accidentally released from a laboratory. This theory is not supported by evidence.[15]

SARS-CoV-2 has close genetic similarity to multiple previously identified bat coronaviruses, suggesting it crossed over into humans from bats.[7][16][17][18][19] Research is ongoing as to whether SARS-CoV-2 came directly from bats or indirectly through an intermediate host, such as pangolins,[20] civets,[21] treeshrews,[22] or raccoon dogs.[23][24] Genomic sequence evidence indicates the spillover event introducing SARS-CoV-2 to humans likely occurred in late 2019.[25][26] As with the 2002–2004 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, efforts to trace the specific geographic and taxonomic origins of SARS-CoV-2 could take years, and results may be inconclusive.[27]

In 2021, the World Health Assembly (on behalf of the WHO) commissioned a study conducted jointly between WHO experts and Chinese scientists.[4][28] Echoing the assessment of most virologists,[29][30][31] the study concluded that the virus most likely had a zoonotic origin in bats, possibly via an intermediate host. It also stated that a laboratory origin for the virus was "extremely unlikely".[32][12] WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in concert with various governments including the US and the EU, responded to the 2021 study report saying the matter still "requires further investigation".[33][34][35] In June 2022, a second round of investigations concluded that more investigations in the various possible pathways of emergence were necessary.[36][37] In July 2021, Zeng Yixin, Vice Health Minister of the Chinese National Health Commission, said that China would not participate in a second phase of investigation, denouncing the decision to proceed as "shocking" and "arrogant".[38][39] In response to the WHO's June 2022 report, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian called the lab leak theory "a lie concocted by anti-China forces for political purposes, which has nothing to do with science".[40]

In July 2022, two papers published in Science described novel epidemiological and genetic evidence that suggested the pandemic likely began at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market and did not come from a laboratory.[41][42][43] In July 2023, a review article in The New York Times details information to date about the origins of the COVID-19 virus.[44]

Origin scenarios

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 has been the subject of debate.[45] There are multiple proposed explanations for how SARS-CoV-2 was introduced into, and evolved adaptations suited to, the human population. There is significant evidence and agreement that the most likely original viral reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 is horseshoe bats, with the closest known viral relatives being RaTG13 and BANAL-52, sampled from horseshoe bat droppings in Yunnan province in China and Feuang, Laos, respectively. The evolutionary distance between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 is estimated to be about 50 years (between 38 and 72 years).[46][47]

The earliest human cases of SARS-CoV-2 were identified in Wuhan, but the index case remains unknown. RaTG13 was sampled from bats in a mine in Mojiang County, Yunnan,[4][48] located roughly 1,500 km (930 mi) away from Wuhan,[49] and there are relatively few bat coronaviruses from Hubei province, where Wuhan is located.[50] Each origin hypothesis attempts to explain this gap in virus evolution and location a different way. These scenarios continue to be investigated to identify the definitive origin of the virus.

Direct zoonotic transmission in a natural setting

The most direct pathway of introduction is direct zoonotic transmission (also known as spillover) from the reservoir species to humans. Scientists consider this to be a highly likely origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in humans. Human contact with bats has increased as human population centers encroach on bat habitats, leading to increased opportunities for spillover. Bats are a significant reservoir species for a diverse range of coronaviruses, and humans have been found with antibodies for them suggesting that this form of direct infection by bats is common. However, in this scenario, the direct ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 remains undiscovered in bats.[4][51] Several social and environmental factors including climate change, natural ecosystem destruction and wildlife trade increased the likelihood for the emergences of zoonosis.[52][53] One study made with the support of the European Union found climate change increased the likelihood of the pandemic by influencing distribution of bat species.[54][55]

Intermediate host

In addition to direct spillover, another pathway, considered highly likely by scientists, is that of transmission through an intermediate host.[10][56] Specifically, this implies that a cross species transmission occurred prior to the human outbreak and that it had pathogenic results on the animal. This pathway has the potential to allow for greater adaptation to human transmission via animals with more similar protein shapes to humans, though this is not required for the scenario to occur. The evolutionary separation from bat viruses is explained in this case by the virus' presence in an unknown species with less viral surveillance than bats.[57] The virus' ability to easily infect and adapt to additional species (including mink) provides evidence that such a route of transmission is possible.[4][56]

Cold/food chain

Another proposed introduction to humans is through fresh or frozen food products, referred to as the cold/food chain.[58] Scientists do not consider this to be a likely origin of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.[59] This scenario's source animal could be either a direct or intermediary species as described above. Many investigations centered around the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which had an early cluster of cases. While there have been food-borne outbreaks of human viruses in the past, and evidence of re-introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into China through imported frozen foods, investigations found no conclusive evidence of viral contamination in products at the Huanan Market.[4][60]

Laboratory incident

The COVID-19 lab leak theory, or lab leak hypothesis, is the idea that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, came from a laboratory. This claim is highly controversial; most scientists believe the virus spilled into human populations through natural zoonosis (transfer directly from an infected non-human animal), similar to the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV outbreaks, and consistent with other pandemics in human history.[61] Available evidence suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was originally harbored by bats, and spread to humans from infected wild animals, functioning as an intermediate host, at the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019.[65][66] Several candidate animal species have been identified as potential intermediate hosts.[73] There is no evidence SARS-CoV-2 existed in any laboratory prior to the pandemic,[74][75][76] or that any suspicious biosecurity incidents happened in any laboratory.[77]

Many scenarios proposed for a lab leak are characteristic of conspiracy theories.[78] Central to many is a misplaced suspicion about the proximity of the outbreak to a virology institute that studies coronaviruses, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). Most large Chinese cities have laboratories that study coronaviruses,[74][79] and virus outbreaks typically begin in rural areas, but are first noticed in large cities.[80] If a coronavirus outbreak occurs in China, there is a high likelihood it will occur near a large city, and therefore near a laboratory studying coronaviruses.[80][81] The idea of a leak at the WIV also gained support due to secrecy during the Chinese government's response.[74][82] The lab leak theory has been described as racist and xenophobic; belief in the lab leak theory is correlated with distrust of government and anti-China sentiment, and has kindled the latter.[83] Scientists from WIV had previously collected SARS-related coronaviruses from bats in the wild, and allegations that they also performed undisclosed risky work on such viruses are central to some versions of the idea.[84][85] Some versions, particularly those alleging genome engineering, are based on misinformation or misrepresentations of scientific evidence.[86][87][88]Mojiang mine incident

Another proposed origin scenario relates to a 2012 incident involving six miners in an abandoned mining cave near the town of Tongguan in Mojiang county, Yunnan, China. Six miners cleaning bat feces fell ill, three of whom died from fatal pneumonia.[89] Out of concerns that the miner's cases could represent a novel disease,[90] serum samples collected from the miners were sent to the Wuhan Institute of Virology and tested by Shi Zhengli and her group for various fatal viruses including Ebola virus, Nipah virus, and SARS-related coronaviruses. The samples tested negative.[91][92][89] In order to uncover other possible causes of the infection, animals (including bats, rats, and musk shrews) were sampled in and around the cave by Shi's group. One such sample from the droppings of Rhinolophus affinis (intermediate horseshoe bat) contained a novel RNA sequence later identified as "RaTG13", which was described in 2020 as the closest relative of SARS-CoV-2 in nature (sharing 96.1% nucleotide identity). In 2022, though, a closer relative to SARS-CoV-2 was discovered by scientists from the Pasteur Institute while conducting field work in Feuang, Laos sampling horseshoe bats: BANAL-52 (96.8% identity).[93][94][95]

Members of DRASTIC, a collection of internet activists, have speculated that RaTG13 could have been a backbone for reverse genetics experiments which they believe created SARS-CoV-2. Scientists have said RaTG-13 is too distantly related to be connected to the pandemic's origins, and could not be altered in a laboratory to create SARS-CoV-2, due to this considerable genetic distance and the amount of time, effort, and resources required for one virus to be mutated into the other.[96] Others have hypothesized that visiting researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology entered the mine and also fell ill with the disease, and later passed it into the general population. This idea has been criticized by scientists in several ways: SARS-CoV-2 has never been detected in the mine, the symptoms displayed by the miners that contracted the disease in 2012 were not typical of COVID-19 symptoms, and it is exceptionally unlikely, given the nature of the virus, that it would have infected so few people between 2012 and 2019 and only reached epidemic proportions after seven years.[97]

Investigations

Chinese government

The first investigation conducted in China was by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, responding to hospitals reporting cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology, resulting in the closure of the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market on 1 January 2020 for sanitation and disinfection.[98] The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) entered the market the same day and took samples; as the animals had been removed before public-health authorities came in, no animals were sampled, although that would have been more conclusive.[99][100]

In April 2020, China imposed restrictions on publishing academic research on the novel coronavirus. Investigations into the origin of the virus would receive extra scrutiny and must be approved by Central Government officials.[101][102] The restrictions do not ban research or publication, including with non-Chinese researchers; Ian Lipkin, a US scientist, has been working with a team of Chinese researchers under the auspices of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, a Chinese government agency, to investigate the origin of the virus. Lipkin has long-standing relationships with Chinese officials, including premier Li Keqiang, because of his contributions to rapid testing for SARS in 2003.[103]

The Huanan live-animal market was suspected of being the source of the virus, as there was a major, early cluster of cases there. On 31 January 2021, a team of scientists led by the World Health Organization visited the market to investigate the origins of COVID-19.[104] Based on the existing evidence, the WHO concluded that the origin of the virus was still unknown, and the Chinese government insisted that the market was not the origin.[105][106][107] The Chinese government has long insisted that the virus originated outside China,[99] and until June 2021 denied that live animals were traded at the Huanan market.[108]

Some Chinese researchers had published a preprint analysis of the Huanan swab samples in February 2022, concluding that the coronavirus in the samples had likely been brought in by humans, not the animals on sale,[99] but omissions in the analysis had raised questions,[108] and the raw sample data had not yet been released.[109][99]

On March 4, 2023, the data from the swab samples of the Huanan live-animal market were released, or possibly leaked;[109] a preliminary analysis of this data was reviewed by the international research community, which said that it made an animal origin much more likely.[108][99] Although the samples do not definitively prove that the raccoon dog is the "missing" intermediate animal host in the bat-to-human transmission chain, it does show that common raccoon dogs were present in the Huanan market at the time of the initial SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, in areas that were also positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and substantially strengthens this hypothesis as the proximal origin of the pandemic.[99][109]

An attempt by these researchers to collaborate with the Chinese researchers was not answered, but the raw data was removed from the online database.[108][99] On March 14, an international group of researchers presented a preliminary analysis at a meeting of the World Health Organization's Scientific Advisory Group for Origins of Novel Pathogens, at which Chinese COVID-19 researchers were also present.[99] On the sixteenth, George Gao, the former head of the CCDC and lead author on the February 2022 preprint, told Science that there was "nothing new" in the raw data, and refused to answer questions about why his research team had removed it from the database.[108][109]

On March 17, the WHO director-general said that the data should have been shared three years earlier, and called on China to be more transparent in its data-sharing.[99] There exists further data from further samples which has not yet been made public.[109][110] Maria Van Kerkhove, the WHO's COVID-19 technical lead, called for it to be made public immediately[99] (see Huanan live-animal market#Swabs).

United States government

Trump administration

On 6 February 2020, the director of the White House's Office of Science and Technology Policy requested the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a meeting of "experts, world class geneticists, coronavirus experts, and evolutionary biologists", to "assess what data, information and samples are needed to address the unknowns, in order to understand the evolutionary origins of COVID-19 and more effectively respond to both the outbreak and any resulting information".[111][112]

In April 2020, it was reported that the US intelligence community was investigating whether the virus came from an accidental leak from a Chinese lab. The hypothesis was one of several possibilities being pursued by the investigators. US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said the results of the investigation were "inconclusive".[113][114] By the end of April 2020, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence said the US intelligence community believed the coronavirus was not man-made or genetically modified.[115][116]

US officials criticised the "terms of reference" allowing Chinese scientists to do the first phase of preliminary research.[28] On 15 January 2021, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that to assist the WHO investigative team's work and ensure a transparent, thorough investigation of COVID-19's origin, the US was sharing new information and urging the WHO to press the Chinese government to address three specific issues, including the illnesses of several researchers inside the WIV in autumn 2019 "with symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illnesses", the WIV's research on "RaTG13" and "gain of function", and the WIV's links to the People's Liberation Army.[117][118] On 18 January, the US called on China to allow the WHO's expert team to interview "care givers, former patients and lab workers" in the city of Wuhan, drawing a rebuke from the Chinese government. Australia also called for the WHO team to have access to "relevant data, information and key locations".[119]

A classified report from May 2020 by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a US government national laboratory, concluded that the hypothesis that the virus leaked from the WIV "is plausible and deserves further investigation", although the report also notes that the virus could have developed naturally, echoing the consensus of the American intelligence community, and provides no "smoking gun" towards either hypothesis.[120][121]

Biden administration

On 13 February 2021, the White House said it had "deep concerns" about both the way the WHO's findings were communicated and the process used to reach them. Mirroring concerns raised by the Trump administration, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan stated that it was essential that the WHO-convened report be independent and "free from alteration by the Chinese government".[122] On 14 April 2021, the Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines, along with other Biden administration officials, said that they had not ruled out the possibility of a laboratory accident as the origin of the COVID-19 virus.[123]

On 26 May 2021, President Joe Biden directed the U.S. intelligence community to produce a report within 90 days on whether the COVID-19 virus originated from a human contact with an infected animal or from an accidental lab leak,[124] stating his national security staff said there is insufficient evidence to determine either hypothesis to be more likely.[125] On 26 August 2021, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released an unclassified summary of their findings,[126] with the main point being that the report remained inconclusive as to the origin of the virus, with intelligence agencies divided on the question.[127] The report also concluded that the virus was most likely not genetically engineered, and that China had no foreknowledge of the virus prior to the outbreak. The report concluded that a final determination of the origin was unlikely without cooperation from the Chinese government, saying their prior lack of transparency "reflect[ed] in part China's government's own uncertainty about where an investigation could lead, as well as its frustration that the international community is using the issue to exert political pressure on China."[128] Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said that the US intelligence report was "unscientific and has no credibility".[129]

On 23 May 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that a previously undisclosed US intelligence report stated that three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology became ill enough in November 2019 to seek hospital care. The report did not specify what the illness was. Officials familiar with the intelligence differed as to the strength to which it corroborates the hypothesis that the virus responsible for COVID-19 was leaked from the WIV. The WSJ report notes that it is not unusual for people in China to go to the hospital with uncomplicated influenza or common cold symptoms.[130]

Yuan Zhiming, director of the WIV's Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory, responded in the Global Times, a Chinese state media outlet, that the "claims are groundless".[131][132] Marion Koopmans, a member of the WHO study team, described the number of flu-like illnesses at the WIV in 2019 as "completely normal".[133] Workers at the WIV must provide yearly serum samples.[4][133] WIV virologist Shi Zhengli said in 2020 that, based on an evaluation of those serum samples, all staff tested negative for COVID-19 antibodies.[130]

The House Foreign Affairs Committee has investigated the origins of the pandemic, and heard classified briefings. The Republican minority issued a report in August 2021 that they believed the origin of the pandemic was an accidental lab escape.[134]

The resurgence of the theory of a laboratory accident was fueled in part by the publication, in May 2021, of early emails between Anthony Fauci and scientists discussing the issue, before deliberate manipulation was ruled out as of March 2020.[135]

On 14 July 2021, the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology held the first congressional hearing on the origins of the virus. Bill Foster, an Illinois Democrat who chaired the hearing, said the Chinese government's lack of transparency is not in itself evidence of a lab leak and cautioned that answers may not be known even after the administration produces its intelligence report.[136] Expert witnesses Stanley Perlman and David Relman presented to the congressman different proposed explanations for the origins of the virus and how to conduct further investigations.[137]

On 16 July 2021, CNN reported that Biden administration officials considered the lab leak theory "as credible" as the natural origins theory.[138] In October 2022, an interim report of a Republican member of a US Senate committee concluded that a lab origin was most likely, but offered "little new evidence", according to The New York Times.[139]

In February of 2023, the United States Energy Department updated its assessment on the origins of the virus, shifting from "undecided" to "low confidence" in favor of a laboratory leak.[140] White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan responded to the report saying there was still "no definitive answer" to the pandemic origins' question.[141]

On 28 February 2023, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation Christopher Wray said the FBI believes Covid-19 most likely originated in the lab.[142]

On 20 March 2023, the COVID-19 Origin Act of 2023 was signed into law. On June 23, 2023, the Biden administration released its report, as required by the Act.[143]

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization has declared that finding where SARS-CoV-2 came from is a priority and that it is "essential for understanding how the pandemic started."[144] In May 2020, the World Health Assembly, which governs the World Health Organization (WHO), passed a motion calling for a "comprehensive, independent and impartial" study into the COVID-19 pandemic. A record 137 countries, including China, co-sponsored the motion, giving overwhelming international endorsement to the study.[145] In mid 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) began negotiations with the government of China on conducting an official study into the origins of COVID-19.

In November 2020, the WHO published a two-phase study plan. The purpose of the first phase was to better understand how the virus "might have started circulating in Wuhan", and a second phase involves longer-term studies based on the findings of the first phase.[4][146] WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom said "We need to know the origin of this virus because it can help us to prevent future outbreaks," adding, "There is nothing to hide. We want to know the origin, and that's it." He also urged countries not to politicise the origin tracing process, saying that would only create barriers to learning the truth.[147]

Phase 1

For the first phase, the WHO formed a team of ten researchers with expertise in virology, public health and animals to conduct a thorough study.[148] One of the team's tasks was to retrospectively ascertain what wildlife was being sold in local wet markets in Wuhan.[149] The WHO's phase one team arrived and quarantined in Wuhan, Hubei, China in January 2021.[119][150]

Members of the team included Thea Fisher, John Watson, Marion Koopmans, Dominic Dwyer, Vladimir Dedkov, Hung Nguyen-Viet, Fabian Leendertz, Peter Daszak, Farag El Moubasher, and Ken Maeda. The team also included five WHO experts led by Peter Ben Embarek, two Food and Agriculture Organization representatives, and two representatives from the World Organisation for Animal Health.[4]

The inclusion of Peter Daszak in the team stirred controversy. Daszak is the head of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit that studies spillover events, and has been a longtime collaborator of over 15 years with Shi Zhengli, Wuhan Institute of Virology's director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases.[151][152] While Daszak is highly knowledgeable about Chinese laboratories and the emergence of diseases in the area, his close connection with the WIV was seen by some as a conflict of interest in the WHO's study.[151][153] When a BBC News journalist asked about his relationship with the WIV, Daszak said, "We file our papers, it's all there for everyone to see."[154]

The team was denied access to raw data, including the list of early patients, swabs, and blood samples.[155] It was allowed only a few hours of supervised access to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.[156]

Findings

In February 2021, after conducting part of their study, the WHO stated that the likely origin of COVID-19 was a zoonotic event from a virus circulating in bats, likely through another animal carrier, and that the time of transmission to humans was likely towards the end of 2019.[105]

The Chinese and the international experts who jointly carried out the WHO-convened study consider it "extremely unlikely" that COVID-19 leaked from a lab.[105][157][158][159] No evidence of a lab leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology was found by the WHO team, with team leader Peter Ben Embarek stating that it was "very unlikely" due to the safety protocols in place.[105] During a 60 Minutes interview with Lesley Stahl, Peter Daszak, another member of the WHO team, described the investigation process to be a series of questions and answers between the WHO team and the Wuhan lab staff. Stahl made the comment that the team was "just taking their word for it", to which Daszak replied, "Well, what else can we do? There's a limit to what you can do and we went right up to that limit. We asked them tough questions. They weren't vetted in advance. And the answers they gave, we found to be believable—correct and convincing."[160]

The investigation also stated that transfer from animals to humans was unlikely to have occurred at the Huanan Seafood Market, since infections without a known epidemiological link were confirmed before the outbreak around the market.[105] In an announcement that surprised some foreign experts, the joint investigation concluded that early transmission via the cold chain of frozen products was "possible".[105]

In March 2021, the WHO published a written report with the results of the study.[161] The joint team stated that there are four scenarios for introduction:[60]

- direct zoonotic transmission to humans (spillover), assessed as "possible to likely"

- introduction through an intermediate host followed by a spillover, assessed as "likely to very likely"

- introduction through the (cold) food chain, assessed as "possible"

- introduction through a laboratory incident, assessed as "extremely unlikely"

The report mentions that direct zoonotic transmission to humans has a precedent, as most current human coronaviruses originated in animals. Zoonotic transmission is also supported by the fact that RaTG13 binds to hACE2, although the fit is not optimal.[4][162]

The investigative team noted the requirement for further studies, noting that these would "potentially increase knowledge and understanding globally."[163][4]: 9

Reactions

WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom, who was not directly involved with the investigation, said he was ready to dispatch additional missions involving specialist experts and that further research was required. He said in a statement, "Some explanations may be more probable than others, but for now all possibilities remain on the table."[164] He also said, "We have not yet found the source of the virus, and we must continue to follow the science and leave no stone unturned as we do." Tedros called on China to provide "more timely and comprehensive data sharing" as part of future investigations.[165]

News outlets noted that, though it was unrealistic to expect quick and huge results from the report, it "offered few clear-cut conclusions regarding the start of the pandemic", "failed to audit the Chinese official position at some parts of the report", and was "biased according to critics".[166][167][168][169] Other scientists praised how the report details the pathways that can shed light on the origin, if explored later.[170]

After the publication of the report, politicians, talk show hosts, journalists, and some scientists advanced unsupported claims that SARS-CoV-2 may have come from the WIV.[171] In the United States, calls to investigate a laboratory leak reached "fever pitch", fueling aggressive rhetoric resulting in antipathy towards people of Asian ancestry,[171][172] and the bullying of scientists.[173][174][175] The European Union, United States, and 13 other countries criticised the WHO-convened study, calling for transparency from China and access to the raw data and original samples.[176] Chinese officials described these criticisms as an attempt to politicise the study.[177] Scientists involved in the WHO report, including Liang Wannian, John Watson, and Peter Daszak, objected to the criticism, and said that the report was an example of the collaboration and dialogue required to successfully continue investigations into the matter.[178]

In a letter published in Science, a number of scientists, including Ralph Baric, argued that the accidental laboratory leak hypothesis had not been sufficiently investigated and remained possible, calling for greater clarity and additional data.[179][8] Their letter was criticized by some virologists and public health experts, who said that a "hostile" and "divisive" focus on the WIV was unsupported by evidence, and would cause Chinese scientists and authorities to share less, rather than more data.[171]

Phase 2

On 27 May 2021, Danish epidemiologist Tina Fischer spoke on the This Week in Virology podcast, advocating for a second phase of the study to audit blood samples for COVID-19 antibodies in China.[180][181] WHO-convened study team member Marion Koopmans, on that same broadcast, advocated for WHO member states to make a decision on the second phase of the study, though she also cautioned that an investigatory audit of the laboratory itself may be inconclusive.[180][181] In early July 2021, WHO emergency chief Michael Ryan said the final details of phase 2 were being worked out in negotiations between WHO and its member states, as the WHO works "by persuasion" and cannot compel any member state (including China) to cooperate.[182]

In July 2021 China rejected WHO requests for greater transparency, cooperation, and access to data as part of Phase 2. On 16 July 2021, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian declared that China's position was that future investigations should be conducted elsewhere and should focus on cold chain transmission and the US military's labs.[183] On 22 July 2021, the Chinese government held a press conference in which Zeng Yixin, Vice Health Minister of the National Health Commission (NHC), said that China would not participate in a second phase of the WHO's investigation, denouncing it as "shocking" and "arrogant".[38] He elaborated "In some aspects, the WHO's plan for next phase of investigation of the coronavirus origin doesn't respect common sense, and it's against science. It's impossible for us to accept such a plan."[39]

On 9 June 2022, the SAGO group, in development of its function of advisor to the WHO, published its first preliminary report. This report summarised existing findings and recommended that further studies be undertaken into possibly pathways of emergence.[36]

The Lancet COVID-19 Commission task force

In November 2020, Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, appointed economist Jeffrey Sachs as chair of its COVID-19 Commission, with wide-ranging goals relating to the virus and pandemic.[184][185][186][187] Sachs set up a number of task forces, including one on the origins of the virus. Sachs appointed Peter Daszak, a colleague of Sachs' at Columbia, to head this task force, two weeks after the Trump administration prematurely ended an federal grant supporting a project led by Daszak, EcoHealth Alliance, which worked with the Wuhan Institute of Virology.[188] This appointment was criticised as creating a conflict of interest, for instance by Richard Ebright, chemical biologist at Rutgers University, who called the commission an "entirely Potemkin commission" in the National Review.[188]

Daszak stated that the task force was formed to "conduct a thorough and rigorous investigation into the origins and early spread of SARS-CoV-2". The task force has twelve members with backgrounds in One Health, outbreak investigation, virology, lab biosecurity and disease ecology.[189][190] The task force planned to analyse scientific findings and did not plan to visit China.[187] However, as Sachs became increasingly drawn to the lab leak theory, he came into conflict with Daszak and his task force.[188] In June 2021, The Lancet announced that Daszak had recused himself from the commission.[191] On 25 September 2021, the task force work was folded after procedural concerns and a need to broaden its scope to examine transparency and government regulation of risky laboratory research.[192] However, it continued to conduct its work independently.[188]

In September 2022, the Lancet commission published a wide-ranging report on the pandemic, including commentary on the virus origin overseen by the group's chairman, economist Jeffrey Sachs.[193] The report suggested that the virus may have originated from an American laboratory, a notion promoted by Sachs since late 2020, including in 2022 on the podcast of anti-vaxx conspiracy theorist Robert F. Kennedy Jr.[188][194][195] Reacting to the Commission report, virologist Angela Rasmussen commented that this may have been "one of The Lancet's most shameful moments regarding its role as a steward and leader in communicating crucial findings about science and medicine".[195] Virologist David Robertson said the invocation of US laboratory involvement was "wild speculation" and that "it's really disappointing to see such a potentially influential report contributing to further misinformation on such an important topic".[195]

The task force published their own report in October 2022, saying they concluded there was "overwhelming" evidence of a natural spillover, but they also accepted the possibility of a lab leak.[188][196]

Independent investigations

In June 2021, the NIH announced that a set of sequence data had been removed from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) in June 2020. The removal was performed according to standard practice at the request of the investigators who owned the rights to the sequences, with the investigators' rationale that the sequences would be submitted to another database.[197][198] The investigators subsequently published a paper in an academic journal the same month they were removed from the NIH database which described the sequences in detail and discussed their evolutionary relationship to other sequences, but did not include the raw data.[199] Virologist David Robertson said that it was difficult to conclude it was a cover-up rather than the more likely explanation: a mundane deletion of data without malfeasance.[200][201] The missing genetic sequence data was restored in a correction published 29 July 2021 after it was stated to be a copy-edit error.[202][203]

In March 2023, an international team of virus experts from University of Arizona, Scripps Research Institute, and University of Sydney found genetic evidence that COVID-19 may have originated from the illegal trade of infected raccoon dogs in Wuhan, China, supporting the zoonotic transmission scenario. Swabs taken from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in January 2020, which tested positive for coronavirus, contained large amounts of genetic material from raccoon dogs.[204]

International calls for investigations

In April 2020, Australian foreign minister Marise Payne and Australian prime minister Scott Morrison called for an independent international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic.[205][206] A few days later, German chancellor Angela Merkel also pressed China for transparency about the origin of the coronavirus, following similar concerns raised by the French president Emmanuel Macron.[207] The UK also expressed support for an investigation, although both France and UK said the priority at the time was to first fight the virus.[208][209] Some public health experts have also called for an independent examination of COVID-19's origins, "arguing WHO does not have the political clout to conduct such a forensic analysis".[210]

In May 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told reporters Canada would "support the call by the United States and others to better understand the origins of COVID-19."[211][212] In June 2021, at the G7 summit in Cornwall, the attending leaders issued a joint statement calling for a new investigation, citing China's refusal to cooperate with certain aspects of the original WHO-convened study.[213] This resistance to international pressure was one of the key findings of a Wall Street Journal investigation into the pandemic origin.[214]

The divisive nature of the debate has led scientists to call for less political pressure on the topic.[135] Public health analysts have remarked that the debate over the origins of SARS-CoV-2 is fueling unnecessary confrontation, resulting in bullying and harassment of scientists,[215] and is deepening existing geopolitical tensions and hindering collaboration at a time where such mutual cooperation is required, both to deal with the current pandemic and in preparation for future such outbreaks.[216][217] This comes in the face of scientists having predicted such events for decades: according to Katie Woolaston, researcher at the Queensland University of Technology, "The environmental drivers of pandemics are not being widely discussed". The debate comes at a moment of difficult global relations with Chinese authorities. Researchers have noted that the politicisation of the debate is making the process more difficult, and that words are often twisted to become "fodder for conspiracy theories".[218][219]

A letter published in The Lancet in July 2021 remarked that the atmosphere of speculation surrounding the issue was of no help in making an objective assessment of the situation.[220] In response to this letter, in a communication published in the same journal, a small group of researchers opposed the idea that scientists should promote unity and called for openness to alternative hypotheses.[221] Despite the unlikelihood of the event, and although definitive answers are likely to take years of research, biosecurity experts have called for a review of global biosecurity policies, citing known gaps in international standards for biosafety.[216][218] The situation has also reignited a debate over gain-of-function research, although the intense political rhetoric surrounding the issue has threatened to sideline serious inquiry over policy in this domain.[222]

See also

- Assessment on COVID-19 Origins

- Proximal Origin

- Scientific Advisory Group for Origins of Novel Pathogens

- World Health Organization's response to the COVID-19 pandemic

References

- ↑ Aguirre, A. Alonso; Catherina, Richard; Frye, Hailey; Shelley, Louise (September 2020). "Illicit Wildlife Trade, Wet Markets, and COVID‐19: Preventing Future Pandemics". World Medical & Health Policy. 12 (3): 256–265. doi:10.1002/wmh3.348. ISSN 1948-4682. PMC 7362142. PMID 32837772.

- ↑ Khan, Shahneaz Ali; Imtiaz, Mohammed Ashif; Islam, Md Mazharul; Tanzin, Abu Zubayer; Islam, Ariful; Hassan, Mohammad Mahmudul (10 May 2022). "Major bat‐borne zoonotic viral epidemics in Asia and Africa: A systematic review and meta‐analysis". Veterinary Medicine and Science. 8 (4): 1787–1801. doi:10.1002/vms3.835. ISSN 2053-1095. PMC 9297750. PMID 35537080.

- ↑ Janicki, Julia; Scarr, Simon; Tai, Catherine (2 March 2021). "Bats and the origin of outbreaks". Reuters. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Virus origin / Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus". WHO. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

WHO-convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2

- ↑ "The COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic has a natural origin, scientists say – Scripps Research's analysis of public genome sequence data from SARS‑CoV‑2 and related viruses found no evidence that the virus was made in a laboratory or otherwise engineered". EurekAlert!. Scripps Research Institute. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ Latinne, Alice; Hu, Ben; Olival, Kevin J.; Zhu, Guangjian; Zhang, Libiao; Li, Hongying; Chmura, Aleksei A.; Field, Hume E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, Carlos; Epstein, Jonathan H.; Li, Bei; Zhang, Wei; Wang, Lin-Fa; Shi, Zheng-Li; Daszak, Peter (25 August 2020). "Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4235. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4235L. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7447761. PMID 32843626.

- 1 2 Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (17 March 2020). "Correspondence: The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- 1 2 Gorman, James; Zimmer, Carl (13 May 2021). "Another Group of Scientists Calls for Further Inquiry Into Origins of the Coronavirus". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ Hu, Ben; Guo, Hua; Zhou, Peng; Shi, Zheng-Li (6 October 2020). "Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. ISSN 1740-1526. PMC 7537588. PMID 33024307.

- 1 2 Kramer, Jillian (30 March 2021). "Here's what the WHO report found on the origins of COVID-19". Science. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

Most scientists are not surprised by the report's conclusion that SARS-CoV-2 most likely jumped from an infected bat or pangolin to another animal and then to a human.

- ↑ This assessment has been made by numerous virologists, geneticists, evolutionary biologists, professional societies, and published in multiple peer-reviewed journal articles.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- 1 2 Horowitz, Josh; Stanway, David (9 February 2021). "COVID may have taken 'convoluted path' to Wuhan, WHO team leader says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ↑ Pauls K, Yates J (27 January 2020). "Online claims that Chinese scientists stole coronavirus from Winnipeg lab have 'no factual basis'". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ↑ "China's rulers see the coronavirus as a chance to tighten their grip". The Economist. 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, Wertheim JO, et al. (August 2021). "The Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Critical Review". Cell. 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

- ↑ Latinne, Alice; Hu, Ben; Olival, Kevin J.; et al. (25 August 2020). "Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4235. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4235L. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7447761. PMID 32843626.

- ↑ Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. Bibcode:2020Natur.579..270Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMC 7095418. PMID 32015507.

- ↑ Perlman S (February 2020). "Another Decade, Another Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 760–762. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126. PMC 7121143. PMID 31978944.

- ↑ Benvenuto D, Giovanetti M, Ciccozzi A, Spoto S, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M (April 2020). "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 455–459. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688. PMC 7166400. PMID 31994738.

- ↑ Shield C (7 February 2020). "Coronavirus: From bats to pangolins, how do viruses reach us?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ↑ Liu, Shan-Lu; Saif, Linda J.; Weiss, Susan R.; Su, Lishan (26 February 2010). "No credible evidence supporting claims of the laboratory engineering of SARS-CoV-2". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 9 (1): 505–507. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1733440. PMC 7054935. PMID 32102621.

- ↑ Flegr, Jaroslav; Zahradník, Daniel; Zemkováa, Michaela (10 April 2022). "Thus spoke peptides: SARS-CoV-2 spike gene evolved in humans and then shortly in rats while the rest of its genome in horseshoe bats and then in treeshrews". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 15 (1): 96–104. doi:10.1080/19420889.2022.2057010. PMC 9009905. PMID 35432715.

- ↑ Lytras, Spyros; Xia, Wei; Hughes, Joseph; Jiang, Xiaowei; Robertson, David L. (17 August 2021). "The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 373 (6558): 968–970. Bibcode:2021Sci...373..968L. doi:10.1126/science.abh0117. PMID 34404734. S2CID 237198809. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ↑ Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020. hdl:10665/330991.

- ↑ "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus – Global subsampling". Nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Cohen J (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611. S2CID 214574620.

- ↑ Cadell, Cate (11 December 2020). "One year on, Wuhan market at epicentre of virus outbreak remains barricaded and empty". Reuters. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- 1 2 Nebehay, Stephanie (10 November 2020). "U.S. denounces terms for WHO-led inquiry into COVID origins". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ↑ Frutos, Roger; Serra-Cobo, Jordi; Chen, Tianmu; Devaux, Christian A. (October 2020). "COVID-19: Time to exonerate the pangolin from the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to humans". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 84: 104493. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104493. ISSN 1567-1348. PMC 7405773. PMID 32768565.

- ↑ Maxmen, Amy; Mallapaty, Smriti (8 June 2021). "The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: what scientists do and don't know". Nature. 594 (7863): 313–315. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..313M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01529-3. PMID 34108722. S2CID 235395594. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ↑ Osuchowski, Marcin F; Winkler, Martin S; Skirecki, Tomasz; Cajander, Sara; Shankar-Hari, Manu; Lachmann, Gunnar; Monneret, Guillaume; Venet, Fabienne; Bauer, Michael; Brunkhorst, Frank M; Weis, Sebastian; Garcia-Salido, Alberto; Kox, Matthijs; Cavaillon, Jean-Marc; Uhle, Florian; Weigand, Markus A; Flohé, Stefanie B; Wiersinga, W Joost; Almansa, Raquel; de la Fuente, Amanda; Martin-Loeches, Ignacio; Meisel, Christian; Spinetti, Thibaud; Schefold, Joerg C; Cilloniz, Catia; Torres, Antoni; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, Evangelos J; Ferrer, Ricard; Girardis, Massimo; Cossarizza, Andrea; Netea, Mihai G; van der Poll, Tom; Bermejo-Martín, Jesús F; Rubio, Ignacio (6 May 2021). "The COVID-19 puzzle: deciphering pathophysiology and phenotypes of a new disease entity". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 9 (6): 622–642. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00218-6. ISSN 2213-2600. PMC 8102044. PMID 33965003.

- ↑ Davidson, Helen (9 February 2021). "WHO team says theory Covid began in Wuhan lab 'extremely unlikely'". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ "Virus origin / Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus". www.who.int.

- ↑ Maxmen, Amy (30 March 2021). "WHO report into COVID pandemic origins zeroes in on animal markets, not labs". Nature. 592 (7853): 173–174. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..173M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00865-8. PMID 33785930. S2CID 232429241. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Shepherd, Christian (31 March 2021). "China rejects WHO criticism and says Covid lab-leak theory 'ruled out'". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 WHO Scientific Advisory for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (9 June 2022). Preliminary Report of the SAGO. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Mueller, Benjamin (12 October 2021). "W.H.O. Will Announce New Team to Study Coronavirus Origins – 'This new group can do all the fancy footwork it wants, but China's not going to cooperate,' one expert said". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- 1 2 Buckley, Chris (22 July 2021). "China denounces the W.H.O.'s call for another look at the Wuhan lab as 'shocking' and 'arrogant.'". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 Ben Westcott, Isaac Yee and Yong Xiong. "Chinese government rejects WHO plan for second phase of Covid-19 origins study". CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "China calls COVID 'lab leak' theory a lie after WHO report". CP24. Associated Press. 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ↑ Maxmen, Amy (27 February 2022). "Wuhan market was epicentre of pandemic's start, studies suggest". Nature. 603 (7899): 15–16. Bibcode:2022Natur.603...15M. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00584-8. PMID 35228730. S2CID 247168739.

- ↑ Pekar JE, Magee A, Parker E, Moshiri N, Izhikevich K, et al. (August 2022). "The molecular epidemiology of multiple zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 960–966. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..960P. doi:10.1126/science.abp8337. PMC 9348752. PMID 35881005.

- ↑ Worobey M, Levy JI, Malpica Serrano L, Crits-Christoph A, Pekar JE, et al. (August 2022). "The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic". Science. 377 (6609): 951–959. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..951W. doi:10.1126/science.abp8715. PMC 9348750. PMID 35881010.

- ↑ Quammen, David (26 July 2023). "The Ongoing Mystery of Covid's Origin - We still don't know how the pandemic started. Here's what we do know — and why it matters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ↑ Frutos, Roger; Pliez, Olivier; Gavotte, Laurent; Devaux, Christian A. (October 2021). "There is no "origin" to SARS-CoV-2". Environmental Research. 207: 112173. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112173. PMC 8493644. PMID 34626592.

- ↑ Boni, Maciej F.; Lemey, Philippe; Jiang, Xiaowei; Lam, Tommy Tsan-Yuk; Perry, Blair W.; Castoe, Todd A.; Rambaut, Andrew; Robertson, David L. (November 2020). "Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1408–1417. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. PMID 32724171. S2CID 220809302.

- ↑ Pomorska-Mól, M.; Włodarek, J.; Gogulski, M.; Rybska, M. (July 2021). "Review: SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks – an overview of current knowledge on occurrence, disease and epidemiology". Animal. 15 (7): 100272. doi:10.1016/j.animal.2021.100272. PMC 8195589. PMID 34126387.

- ↑ Zhou, Hong; Chen, Xing; Hu, Tao; Li, Juan; Song, Hao; Liu, Yanran; Wang, Peihan; Liu, Di; Yang, Jing; Holmes, Edward C.; Hughes, Alice C.; Bi, Yuhai; Shi, Weifeng (June 2020). "A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein". Current Biology. 30 (11): 2196–2203.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. ISSN 1879-0445. PMC 7211627. PMID 32416074.

- ↑ Stanway, David (9 June 2021). "Explainer: China's Mojiang mine and its role in the origins of COVID-19". Reuters. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ↑ Zhang, Yong-Zhen; Holmes, Edward C. (April 2020). "A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2". Cell. 181 (2): 223–227. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035. PMC 7194821. PMID 32220310.

- ↑ Wacharapluesadee, Supaporn; Tan, Chee Wah; Maneeorn, Patarapol; Duengkae, Prateep; Zhu, Feng; Joyjinda, Yutthana; Kaewpom, Thongchai; Chia, Wan Ni; Ampoot, Weenassarin; Lim, Beng Lee; Worachotsueptrakun, Kanthita; Chen, Vivian Chih-Wei; Sirichan, Nutthinee; Ruchisrisarod, Chanida; Rodpan, Apaporn; Noradechanon, Kirana; Phaichana, Thanawadee; Jantarat, Niran; Thongnumchaima, Boonchu; Tu, Changchun; Crameri, Gary; Stokes, Martha M.; Hemachudha, Thiravat; Wang, Lin-Fa (9 February 2021). "Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 972. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..972W. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7873279. PMID 33563978.

- ↑ Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Services. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). IPCC. 2022. pp. 233–235. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ↑ Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). IPCC. 2022. pp. 1067–1070. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ↑ "Climate change may have driven the emergence of SARS-CoV-2". University of Cambridge. Science of the Total Environment. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ↑ "Climate change the culprit in the COVID-19 pandemic". European Commission. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- 1 2 Banerjee, Arinjay; Doxey, Andrew C.; Mossman, Karen; Irving, Aaron T. (1 March 2021). "Unraveling the Zoonotic Origin and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 36 (3): 180–184. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.12.002. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 7733689. PMID 33384197.

- ↑ Frutos, Roger; Serra-Cobo, Jordi; Chen, Tianmu; Devaux, Christian A (1 October 2020). "COVID-19: Time to exonerate the pangolin from the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to humans". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 84: 104493. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104493. ISSN 1567-1348. PMC 7405773. PMID 32768565.

- ↑ "Can Frozen Food Spread The Coronavirus?". NPR. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ "Origins of the COVID-19 Pandemic". Congressional Research Service. 11 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- 1 2 Lardieri, Alexa (9 February 2021). ""WHO: 'Extremely Unlikely' Coronavirus Came From Lab in China"". US News. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ See numerous reliable sources which support this:

- Pekar, Jonathan (26 July 2022). "The molecular epidemiology of multiple zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 960–966. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..960P. doi:10.1126/science.abp8337. PMC 9348752. PMID 35881005.

- Jiang, Xiaowei; Wang, Ruoqi (25 August 2022). "Wildlife trade is likely the source of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 925–926. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..925J. doi:10.1126/science.add8384. PMID 36007033. S2CID 251843410. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

Although the most probable reservoir animal for SARS-CoV-2 is Rhinolophus bats (2, 3), zoonotic spillovers likely involve an intermediate animal.

- Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, et al. (September 2021). "The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review". Cell (Review). 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

As for the vast majority of human viruses, the most parsimonious explanation for the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic event...There is currently no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 has a laboratory origin. There is no evidence that any early cases had any connection to the WIV, in contrast to the clear epidemiological links to animal markets in Wuhan, nor evidence that the WIV possessed or worked on a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 prior to the pandemic.

- Bolsen, Toby; Palm, Risa; Kingsland, Justin T. (October 2020). "Framing the Origins of COVID-19". Science Communication. 42 (5): 562–585. doi:10.1177/1075547020953603. ISSN 1075-5470. S2CID 221614695. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

Individuals may learn about the origins of COVID-19 through exposure to stories that communicate either what most scientists believe (i.e., zoonotic transmission) or through exposure to conspiratorial claims (e.g., the virus was created in a research laboratory in China).

- Robertson, Lori (2 March 2023). "Still No Determination on COVID-19 Origin". FactCheck.org. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

most scientists suspect a zoonotic spillover in which the virus transferred from bats, or through an intermediate animal, to humans — the same way the SARS and MERS coronaviruses originated.

- Gajilan, A. Chris (19 September 2021). "Covid-19 origins: Why the search for the source is vital". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

The zoonotic hypothesis hinges on the idea that the virus spilled over from animals to humans, either directly through a bat, or through some other intermediary animal. Most scientists say that this is the likely origin, given that 75% of all emerging diseases have jumped from animals into humans.

- McDonald •, Jessica (28 June 2021). "Where Did COVID-19 Start? The Facts and Mysteries of Its Origin". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

The default answer for most scientists has been that the virus, SARS-CoV-2, probably made the jump to humans from bats, if it was a direct spillover — or, more likely, through one or more intermediate mammals.

- MCKEEVER, AMY (6 April 2021). "We still don't know the origins of the coronavirus. Here are 4 scenarios". National Geographic. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

The most controversial hypothesis for the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is also the one that most scientists agree is the least likely: that the virus somehow leaked out of a laboratory in Wuhan where researchers study bat coronaviruses.

- Ball, Philip. "Three years on, Covid lab-leak theories aren't going away. This is why". www.prospectmagazine.co.uk.

The leading theory now backed by most scientists is that the virus arose in wild bats and found its way into animals (perhaps via a pangolin or a civet cat) sold at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.

- Jackson, Christina (21 September 2020). "Controversy Aside, Why the Source of COVID-19 Matters". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

Most scientists studying the origins of COVID-19 have concluded that the SARS-CoV-2 virus probably evolved naturally and infected humans via incidental contact with a wild or domesticated animal.

- McCarthy, Simone (16 September 2021). "Bat-human virus spillovers may be very common, study finds". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

Questions have been raised about whether the virus could have leaked from a laboratory studying related viruses in Wuhan – a scenario most scientists...feel is less likely than a natural spillover.

- Danner, Chas (26 May 2021). "Biden Joins the COVID Lab-Leak-Theory Debate". Intelligencer. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

There continues to be no evidence at all for the conspiracy theory that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, was developed as some kind of bioweapon, and most scientists believe that the majority of available evidence indicates the virus jumped from animal to human.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl; Mueller, Benjamin (26 February 2022). "New Research Points to Wuhan Market as Pandemic Origin". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ↑ Worobey M, Levy JI, Malpica Serrano L, Crits-Christoph A, Pekar JE, et al. (August 2022). "The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic". Science. 377 (6609): 951–959. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..951W. doi:10.1126/science.abp8715. PMC 9348750. PMID 35881010.

- ↑ Pekar JE, Magee A, Parker E, Moshiri N, Izhikevich K, et al. (August 2022). "The molecular epidemiology of multiple zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 960–966. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..960P. doi:10.1126/science.abp8337. PMC 9348752. PMID 35881005.

- ↑ There were two landmark origins studies published side-by-side in Science in July 2022:[62]

- 1 2 Jiang, Xiaowei; Wang, Ruoqi (25 August 2022). "Wildlife trade is likely the source of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 377 (6609): 925–926. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..925J. doi:10.1126/science.add8384. PMID 36007033. S2CID 251843410. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ↑ Alkhovsky, S; Lenshin, S; Romashin, A; Vishnevskaya, T; Vyshemirsky, O; Bulycheva, Y; Lvov, D; Gitelman, A (9 January 2022). "SARS-like Coronaviruses in Horseshoe Bats (Rhinolophus spp.) in Russia, 2020". Viruses. 14 (1): 113. doi:10.3390/v14010113. PMC 8779456. PMID 35062318.

- ↑ Frazzini, Sara; Amadori, Massimo; Turin, Lauretta; Riva, Federica (7 October 2022). "SARS CoV-2 infections in animals, two years into the pandemic". Archives of Virology. 167 (12): 2503–2517. doi:10.1007/s00705-022-05609-1. PMC 9543933. PMID 36207554.

- ↑ Fenollar, Florence; Mediannikov, Oleg; Maurin, Max; Devaux, Christian; Colson, Philippe; Levasseur, Anthony; Fournier, Pierre-Edouard; Raoult, Didier (1 April 2021). "Mink, SARS-CoV-2, and the Human-Animal Interface". Frontiers in Microbiology. Frontiers Media SA. 12: 663815. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.663815. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 8047314. PMID 33868218.

- ↑ Zhao, Jie; Cui, Wei; Tian, Bao-ping (2020). "The Potential Intermediate Hosts for SARS-CoV-2". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 580137. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.580137. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 7554366. PMID 33101254.

- ↑ Qiu, Xinyu; Liu, Yi; Sha, Ailong (28 September 2022). "SARS‐CoV‐2 and natural infection in animals". Journal of Medical Virology. 95 (1): jmv.28147. doi:10.1002/jmv.28147. PMC 9538246. PMID 36121159.

- ↑ Gupta, SK; Minocha, R; Thapa, PJ; Srivastava, M; Dandekar, T (14 August 2022). "Role of the Pangolin in Origin of SARS-CoV-2: An Evolutionary Perspective". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (16): 9115. doi:10.3390/ijms23169115. PMC 9408936. PMID 36012377.

- ↑ Suggestions for intermediate animal hosts between horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus spp.)[67] and humans have included:

- 1 2 3 Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, et al. (September 2021). "The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review". Cell (Review). 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

Under any laboratory escape scenario, SARS-CoV-2 would have to have been present in a laboratory prior to the pandemic, yet no evidence exists to support such a notion and no sequence has been identified that could have served as a precursor.

- ↑ Gorski, David (31 May 2021). "The origin of SARS-CoV-2, revisited". Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

The second [version of the lab leak] is the version that "reasonable" people consider plausible, but there is no good evidence for either version.

- ↑ Holmes, Edward C. (14 August 2022). "The COVID lab leak theory is dead. Here's how we know the virus came from a Wuhan market". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

For the lab leak theory to be true, SARS-CoV-2 must have been present in the Wuhan Institute of Virology before the pandemic started. This would convince me. But the inconvenient truth is there's not a single piece of data suggesting this. There's no evidence for a genome sequence or isolate of a precursor virus at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Not from gene sequence databases, scientific publications, annual reports, student theses, social media, or emails. Even the intelligence community has found nothing. Nothing. And there was no reason to keep any work on a SARS-CoV-2 ancestor secret before the pandemic.

- ↑ "COVID-19 lab leak theory ends with a whimper, not a bang". Sydney Morning Herald. 27 June 2023.

- ↑ Lewandowsky S, Jacobs PH, Neil S (2023). "Chapter 2: Leak or Leap? Evidence and Cognition Surrounding the Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus". In Butter M, Knight P (eds.). Covid Conspiracy Theories in Global Perspective. Taylor & Francis. pp. 26–39. doi:10.4324/9781003330769-2. ISBN 9781032359434.

- ↑ Garry, Robert F. (10 November 2022). "The evidence remains clear: SARS-CoV-2 emerged via the wildlife trade". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (47): e2214427119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11914427G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2214427119. eISSN 1091-6490. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9704731. PMID 36355862.

- 1 2 Frutos, Roger; Pliez, Olivier; Gavotte, Laurent; Devaux, Christian A. (May 2022). "There is no 'origin' to SARS-CoV-2". Environmental Research. 207: 112173. Bibcode:2022ER....207k2173F. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112173. ISSN 0013-9351. PMC 8493644. PMID 34626592.

- ↑ Maxmen, Amy; Mallapaty, Smriti (8 June 2021). "The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: what scientists do and don't know". Nature. 594 (7863): 313–315. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..313M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01529-3. PMID 34108722. S2CID 235395594.

- ↑ Dyer, Owen (27 July 2021). "Covid-19: China stymies investigation into pandemic's origins". BMJ. 374: n1890. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1890. PMID 34315713. n1890.

- ↑ Perng W, Dhaliwal SK (May 2022). "Anti-Asian Racism and COVID-19: How It Started, How It Is Going, and What We Can Do". Epidemiology. 33 (3): 379–382. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001458. PMC 8983612. PMID 34954709.

- ↑ Baker, Nicholson (4 January 2021). "The Lab-Leak Hypothesis". New York Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Rowan (29 June 2021). "Inside the risky bat-virus engineering that links America to Wuhan". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

Ebright believes one factor at play was the cost and inconvenience of working in high-containment conditions. The Chinese lab's decision to work at BSL-2, he says, would have 'effectively increas[ed] rates of progress, all else being equal, by a factor of 10 to 20'.

- ↑ Krishnaswamy, S.; Govindarajan, T. R. (16 July 2021). "The controversy being created about the origins of the virus that causes COVID-19". Frontline. Chennai. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ Kasprak, Alex (16 July 2021). "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a COVID Lab Leak". Snopes. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ Hakim, Mohamad S. (14 February 2021). "SARS‐CoV‐2, Covid‐19, and the debunking of conspiracy theories". Reviews in Medical Virology. 31 (6): e2222. doi:10.1002/rmv.2222. PMC 7995093. PMID 33586302.

- 1 2 Wu Z, Yang L, Yang F, Ren X, Jiang J, Dong J, et al. (June 2014). "Novel Henipa-like virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in rats, China, 2012". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): 1064–6. doi:10.3201/eid2006.131022. PMC 4036791. PMID 24865545.

- ↑ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes.com. Snopes. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (December 2020). "Addendum: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 588 (7836): E6. Bibcode:2020Natur.588E...6Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z. PMC 9744119. PMID 33199918.

- ↑ Ge XY, Wang N, Zhang W, Hu B, Li B, Zhang YZ, et al. (February 2016). "Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft". Virologica Sinica. 31 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1007/s12250-016-3713-9. PMC 7090819. PMID 26920708.

- ↑ Temmam, Sarah; Vongphayloth, Khamsing; Salazar, Eduard Baquero; Munier, Sandie; Bonomi, Max; Régnault, Béatrice; Douangboubpha, Bounsavane; Karami, Yasaman; Chretien, Delphine; Sanamxay, Daosavanh; Xayaphet, Vilakhan (February 2022). "Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells". Nature. 604 (7905): 330–336. Bibcode:2022Natur.604..330T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4. PMID 35172323. S2CID 246902858.

- ↑ Mallapaty, Smriti (24 September 2021). "Closest known relatives of virus behind COVID-19 found in Laos". Nature. 597 (7878): 603. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..603M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02596-2. PMID 34561634. S2CID 237626322.

- ↑ "Newly Discovered Bat Viruses Give Hints to Covid's Origins". New York Times. 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Frutos, Roger; Javelle, Emilie; Barberot, Celine; Gavotte, Laurent; Tissot-Dupont, Herve; Devaux, Christian A. (March 2022). "Origin of COVID-19: Dismissing the Mojiang mine theory and the laboratory accident narrative". Environmental Research. 204 (Pt B): 112141. Bibcode:2022ER....204k2141F. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112141. ISSN 0013-9351. PMC 8490156. PMID 34597664.

- ↑ Frutos, Roger; Javelle, Emilie; Barberot, Celine; Gavotte, Laurent; issot-Dupont, Herve; Devaux, Christian A. (March 2022). "Origin of COVID-19: Dismissing the Mojiang mine theory and the laboratory accident narrative". Environmental Research. 204 (Pt B): 112141. Bibcode:2022ER....204k2141F. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112141. PMC 8490156. PMID 34597664.

- ↑ "WHO | Pneumonia of unknown cause – China". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wu, Katherine J. (17 March 2023) [Originally published 16 March 2023]. "The Strongest Evidence Yet That an Animal Started the Pandemic". The Atlantic. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (21 March 2022). "'He Goes Where the Fire Is': A Virus Hunter in the Wuhan Market". The New York Times.

- ↑ Gan, Nectar; Hu, Caitlin; Watson, Ivan (12 April 2020). "China imposes restrictions on research into origins of coronavirus". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Kang, Dake; Cheng, Maria; Mcneil, Sam (30 December 2020). "China clamps down in hidden hunt for coronavirus origins". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Manson, Katrina; Yu, Sun (26 April 2020). "US and Chinese researchers team up for hunt into Covid origins". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ Peter, Martin Quin Pollard, Thomas (31 January 2021). "WHO team visits Wuhan market where first COVID infections detected". Reuters. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fujiyama, Emily Wang; Moritsugu, Ken (11 February 2021). "EXPLAINER: What the WHO coronavirus experts learned in Wuhan". AP News. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ Areddy, James T. (26 May 2020). "China Rules Out Animal Market and Lab as Coronavirus Origin". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ Mackenzie, John S.; Smith, David W. (17 March 2020). "COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don't". Microbiology Australia. 41: 45. doi:10.1071/MA20013. ISSN 1324-4272. PMC 7086482. PMID 32226946.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Unearthed genetic sequences from China market may point to animal origin of COVID-19". www.science.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mueller, Benjamin (17 March 2023). "New Data Links Pandemic's Origins to Raccoon Dogs at Wuhan Market". The New York Times.

- ↑ Hvistendahl, Mara; Mueller, Benjamin (23 April 2023). "Chinese Censorship Is Quietly Rewriting the Covid-19 Story". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ↑ "OSTP Coronavirus Request to NASEM" (PDF). nationalacademies.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ Gittleson, Ben (6 February 2020). "White House asks scientists to investigate origins of coronavirus". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Campbell, Josh; Atwood, Kylie; Perez, Evan (16 April 2020). "US explores possibility that coronavirus spread started in Chinese lab, not a market". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Dilanian, Ken; Kube, Courtney (16 April 2020). "U.S. intel community examining whether coronavirus emerged accidentally from a Chinese lab". NBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Singh, Maanvi; Davidson, Helen; Borger, Julian (30 April 2020). "Trump claims to have evidence coronavirus started in Chinese lab but offers no details". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Pompeo, Michael R. (15 January 2021). "Ensuring a Transparent, Thorough Investigation of COVID-19's Origin – United States Department of State". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: Activity at the Wuhan Institute of Virology". United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- 1 2 Nebehay, Stephanie (18 January 2021). "U.S. and China clash at WHO over scientific mission in Wuhan". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Strobel, Michael R. Gordon and Warren P. (8 June 2021). "U.S. Report Found It Plausible Covid-19 Leaked From Wuhan Lab". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ↑ Bo Williams, Katie; Bertrand, Natasha; Cohen, Zachary. "Classified report with early support for lab leak theory reemerges as focal point for lawmakers digging into Covid-19 origins". CNN.

- ↑ Andrea Shalal (13 February 2021). "White House cites 'deep concerns' about WHO COVID report, demands early data from China". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Jenna (14 April 2021). "Biden's top intelligence officials won't rule out lab accident theory for COVID-19 origins". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ John Wagner (26 May 2021). "Biden asks intelligence community to redouble efforts to determine definitive origin of the coronavirus". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ "Explainer: What we know about the origins of COVID-19". Reuters. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ "Unclassified Summary of Assessment on COVID-19 Origins" (PDF). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 26 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ Cohen, Jon (27 August 2021). "COVID-19's origins still uncertain, U.S. intelligence agencies conclude". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ Nakashima, Ellen; Achenbach, Joel (27 August 2021). "U.S. spy agencies rule out possibility the coronavirus was created as a bioweapon, say origin will stay unknown without China's help". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ "China says U.S. COVID origins report is without credibility". Reuters. Reuters. 1 November 2021.

- 1 2 Hinshaw, Michael R. Gordon, Warren P. Strobel and Drew (23 May 2021). "Intelligence on Sick Staff at Wuhan Lab Fuels Debate on Covid-19 Origin". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Terry, Mark (24 May 2021). "New Report Says Wuhan Researchers Possibly Ill With COVID-19 in November 2019". BioSpace. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ↑ "New information on Wuhan researchers' illness furthers debate on pandemic origins". CNN. 23 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- 1 2 "WHO team scientist: Wuhan lab workers fell sick in 2019". NBC News. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Michael McCaul (August 2021). "The origins of COVID-19: An investigation of the Wuhan Institute of Virology" (PDF). House Foreign Affairs Committee.

- 1 2 Spinney, Laura (18 June 2021). "In hunt for Covid's origin, new studies point away from lab leak theory". The Guardian.

- ↑ Groppe, Maureen. "Mike Pence: Evidence 'strongly suggests' COVID-19 came from a Chinese lab". USA Today. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ "House Hearing Grapples with COVID Origin and 'Lab-Leak' Theory". 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Bertrand, Natasha; Brown, Pamela; Williams, Katie Bo; Cohen, Zachary (16 July 2021). "Senior Biden officials finding that Covid lab leak theory as credible as natural origins explanation". CNN. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ Mueller, Benjamin; Zimmer, Carl (27 October 2022). "G.O.P. Senator's Report on Covid Origins Suggests Lab Leak, but Offers Little New Evidence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ↑ Bertrand, Jeremy Herb,Natasha (26 February 2023). "US Energy Department assesses Covid-19 likely resulted from lab leak, furthering US intel divide over virus origin | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mueller, Julia (26 February 2023). "National security adviser: No 'definitive answer' on COVID lab leak". The Hill. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ↑ Max Matza & Nicholas Yong (1 March 2023). "FBI chief Christopher Wray says China lab leak most likely". BBC.

- ↑ Office of the Director of National Intelligence. "Report-on-Potential-Links-Between-the-Wuhan-Institute-of-Virology-and-the-Origins-of-COVID-19" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2023.

- ↑ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the Member State Information Session on Origins". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 July 2021.