Post COVID-19 condition

| Post COVID-19 condition | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Long COVID,[1] post-COVID,[1] persistent post-COVID syndrome (PPCS),[2] chronic COVID syndrome (CCS), COVID long-haulers,[3] post COVID-19 syndrome,[4] post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection,[5] post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC)[6] | |

| |

| An individual with fatigue | |

| Specialty | Multidisciplinary |

| Symptoms | Tiredness, shortness of breath, headaches, anxiety and depression, loss of smell, difficulty concentrating, fever, palpitations[1] |

| Usual onset | >4 weeks post COVID-19[5] |

| Types | Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS), post-intensive care syndrome (PICS)[5] |

| Causes | COVID-19[5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other causes[7] |

| Prevention | Preventing COVID-19[1] |

| Treatment | Addressing specific symptoms[8] |

| Frequency | ~20 to 60%[9][10] |

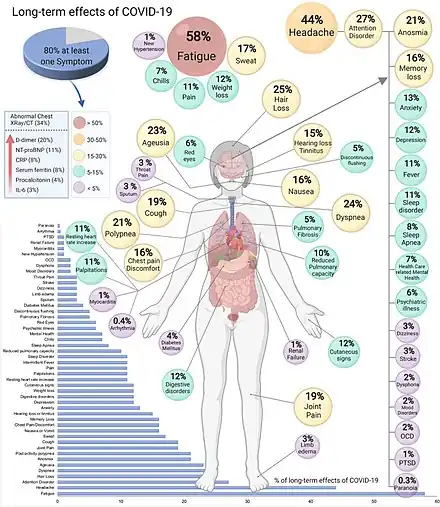

Post COVID-19 condition, which includes long COVID, are a group of conditions that occur after having COVID-19.[1][11] It involves symptoms that occur four or more weeks after the initial infection.[1] Symptoms may include tiredness, shortness of breath, headaches, anxiety and depression, loss of smell, difficulty concentrating, headaches, fever, and palpitations.[1] Symptoms may also get worse with activity.[1]

It may occur in anyone following COVID-19, regardless of the severity of the original infection.[1] A number of cases have occurred in those infected despite being vaccination; though it is less common in this group.[12] Those who have had severe illness may also have damage to multiple organ system, develop autoimmune conditions, post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[1][5] Children may experience multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).[1]

The case definition is still being developed.[5] There are no specific laboratory or imaging findings that confirm or rules out the condition; though other potential causes should be excluded.[8][7]

Prevention is by preventing COVID-19, including vaccination, physical distancing, and wearing a face mask.[1] Treatment involves efforts to address specific symptoms and improve physical, mental, and social wellbeing.[8] Specialized clinics have been created, in certain jurisdictions, to try to address the condition.[13][14] About 20% of people diagnosed with COVID have symptoms for longer than 4 weeks and 10% of people for longer than 12 weeks.[9] Women are more commonly affected than men.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Long-term health problems can occur after the typical recovery period—of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Such problems include respiratory system disorders, nervous system and neurocognitive disorders, mental health disorders, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, tiredness, musculoskeletal pain, and anemia.[16]

Varying combinations of symptoms that have been reported weeks or months following COVID-19, whether the initial illness was severe, mild or without symptoms, are numerous.[17][18] They include:

- Tiredness[17]

- Headache[17]

- Cough[17]

- Muscle and joint pain[17]

- Fever[17]

- Inability to concentrate ("brain fog")[17]

- Anxiety and depression[17]

- Memory loss[18]

- Loss of smell[17]

- Loss of taste[17]

- Sleep difficulties[16]

- Needle pains in arms and legs

- Diarrhoea and bouts of vomiting

- Sore throat and difficulties to swallow

- Skin rash[16]

- Shortness of breath[17]

- Chest pain[17]

- Fast beating heart[17]

- Changes in oral health (teeth, saliva, gums)

- Parosmia (changes smells)

- Tinnitus

- Dizziness on standing[18]

Other problems reported following COVID-19 include:

Cause

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

It is unknown why most people recover fully within two to three weeks and others experience symptoms for long.[19] It is hypothesized that ongoing long COVID symptoms may be due to four syndromes:[20][21]

- permanent damage to the lungs and heart,

- post-intensive care syndrome,

- Post-viral fatigue, sometimes regarded as the same as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), and

- continuing COVID-19 symptoms.

Other situations that might cause new and ongoing symptoms include:

- the virus being present for a longer time than usual, due to an ineffective immune response;[19]

- reinfection (e.g., with another strain of the virus);[19]

- damage caused by inflammation and a strong immune response to the infection;[19]

- physical deconditioning due to a lack of exercise while ill;[19] and

- post-traumatic stress or other mental sequelae,[19] especially in people who had previously experienced anxiety, depression, insomnia, or other mental health difficulties.[22]

Risk factors

Risk factors may include:[23][24][25]

- Age – particularly those aged over 50

- Excess weight

- Asthma

- Reporting more than five symptoms (e.g. more than cough, fatigue, headache, diarrhoea, loss of sense of smell) in the first week of COVID-19 infection; five is the median number reported

Women are less likely to develop severe acute COVID but more likely to develop long COVID than men.[26] Some research suggests this is due primarily to hormonal differences,[27][28] while other research points to other factors, including chromosomal genetics, sex-dependent differences in immune system behavior, and non-biological factors may be relevant.[26]

Diagnosis

Most people affected by COVID-19 make a full recovery within three months, but for some the symptoms last longer.[29][30] Long COVID has no single clear definition.[26] Generally, people who have ongoing symptoms lasting longer than expected after recovering from COVID-19 are classed as having long COVID. The term has been used to describe the presence of symptoms lasting longer than 12 weeks. It has also been used to describe those who required intensive care, and those who did not require hospital admission but later presented with or without symptoms and signs of end-organ damage such as cardiac or respiratory disease.[31]

British definition

The British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) divides COVID-19 into three clinical definitions:

- acute COVID-19 for signs and symptoms during the first 4 weeks after infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),

- new or ongoing symptoms 4 weeks or more after the start of acute COVID-19, which is divided into:

- ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 for effects from 4 to 12 weeks after onset, and

- post-COVID-19 syndrome for effects that persist 12 or more weeks after onset.

NICE describes the term long COVID, which it uses "in addition to the clinical case definitions", as "commonly used to describe signs and symptoms that continue or develop after acute COVID-19. It includes both ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 (from 4 to 12 weeks) and post-COVID-19 syndrome (12 weeks or more)".[32] NICE defines post-COVID-19 syndrome as "Signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID‑19, continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. It usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which can fluctuate and change over time and can affect any system in the body. Post‑COVID‑19 syndrome may be considered before 12 weeks while the possibility of an alternative underlying disease is also being assessed".[32]

US definition

In February 2021, the National Institutes of Health said symptoms of long COVID can include fatigue, shortness of breath, "brain fog", sleep disorders, intermittent fevers, gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, and depression. Symptoms can persist for months and can range from mild to incapacitating, with new symptoms arising well after the time of infection. NIH Director Francis Collins said the condition can be collectively referred to as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).[33]

Differential diagnosis

Long COVID is similar to post-Ebola syndrome and the post-infection syndromes seen in chikungunya and the infections that appear to trigger ME/CFS, and the pathophysiology of long COVID may be similar to these other conditions.[26] Some people with long COVID in Canada have been diagnosed with ME/CFS, a multi-system neurological disease that is believed to be triggered by an infectious illness in the majority of cases". Lucinda Bateman, a specialist in ME/CFS in Salt Lake City in the US believes that the two syndromes are identical. There is need for more research into ME/CFS; Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to the US government, said that COVID-19 is a "well-identified etiologic agent that should be very helpful now in getting us to be able to understand [ME?CFS]”.[34]

Managemnt

In terms of treatment for this condition, long COVID, the following is advisable:[35]

- Symptomatic treatment

- Physiotherapy

- Chest physiotherapy

- Occupational therapy

- Psychological support

Epidemiology

Some reports of long-term illness after infection appeared early during the COVID-19 pandemic,[36][20] including in people who had a mild or moderate initial infection[37] as well as those who were admitted to hospital with more severe infection.[38][39]

As of January 2021, the precise incidence was unknown. The incidence declines over time, as many people slowly recover. Some early studies suggested that between 20% and 33% of people with COVID-19 experienced symptoms lasting longer than a month.[9][40] A telephone survey in the US in the first half of 2020 showed that about 35% of people who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 experienced a range of symptoms that lasted longer than three weeks.[41] As of December 2020, the Office of National Statistics in the UK estimated that, of all people with a positive test for SARS-CoV-2, about 21% experienced symptoms for longer than five weeks, and about 10% experienced symptoms for longer than 12 weeks.[9][42][43]

Some studies have suggested that some children experience lingering symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection.[9][44][45]

Although anyone who gets infected can develop long COVID, people who become so sick that they require hospitalization take longer to recover. A majority (up to 80%[46]) of those who were admitted to hospital with severe disease experience long-term problems including fatigue and shortness of breath (dyspnoea).[20][47][48] Patients with severe initial infection, particularly those who required mechanical ventilation to help breathing, are also likely to suffer from post-intensive care syndrome following recovery.[38] A study of patients who had been hospitalised in Wuhan found that the majority still had at least one symptom after six months. Patients who had been more severely ill still showed severe incapacity in lung function.[49] Among the 1733 patients who had been discharged from hospital and followed up about six months later, the most common symptoms were fatigue or muscle weakness (63%), sleep difficulties (26%), and anxiety or depression (23%).[50]

Some people suffer long-term neurologic symptoms despite never having been hospitalized for COVID-19; the first study of this population was published in March 2021. Most frequently, these non-hospitalized patients experienced "prominent and persistent 'brain fog' and fatigue that affect their cognition and quality of life."[51][52]

In January 2021, a large study in Wuhan, China, showed that 76% of people admitted with COVID-19, still had at least one symptom six months later.[53] In the same month, a study in the UK reported that 30% of recovered patients were readmitted to hospital within 140 days, and 12% of the total died. Many patients had developed diabetes for the first time, as well as problems with heart, liver and kidney problems. The mode of insulin failure was at that point unknown.[54]

In March 2021, the Indonesian Doctors Association, in a survey of 463 people, suggested that 63.5% of respondents self-reported lingering symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The exact set of symptoms was not specified, however, according to the article, fatigue and cough were the most commonly reported symptoms, followed by muscle pain and headache.[55]

History

Elisa Perego, an archaeologist at University College London, first used term Long COVID as a hashtag on Twitter in May 2020.[56][57]

Society and culture

Health system response

United States

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci has described long-term Covid-19 as “...a phenomenon that is really quite real and quite extensive,” but also said that the number of cases is unknown.[58]

On February 23, 2021, National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins announced a major initiative to identify the causes and ultimately the means of prevention and treatment of people who are suffering from Long COVID.[33] Part of this initiative includes the creation of the COVID-19 Project.[59]

Australia

In October 2020, a guide published by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) says that ongoing post-COVID-19 infection symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath and chest pain will require management by GPs, in addition to the more severe conditions already documented.[46]

United Kingdom

In Britain, the National Health Service set up specialist clinics for the treatment of long COVID.[60] The four Chief Medical Officers of the UK were warned of academic concern over long COVID on 21 September 2020 in a letter written by Trisha Greenhalgh published in The BMJ[61] signed by academics including David Hunter, Martin McKee, Susan Michie, Melinda Mills, Christina Pagel, Stephen Reicher, Gabriel Scally, Devi Sridhar, Charles Tannock, Yee Whye Teh, and Harry Burns, former CMO for Scotland.[61] In October 2020, NHS England's head Simon Stevens announced the NHS had committed £10 million to be spent that year on setting up long COVID clinics to assess patients' physical, cognitive, and psychological conditions and to provide specialist treatment. Future clinical guidelines were announced, with further research on 10,000 patients planned and a designated task-force to be set up, along with an online rehabilitation service[62] – "Your Covid Recovery".[63] The clinics include a variety of medical professionals and therapists, with the aim of providing "joined-up care for physical and mental health”.[43]

The National Institute for Health Research has allocated funding for research into the mechanisms behind symptoms of Long COVID.[43]

In December 2020, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) opened a second Long Covid clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery for patients with post-Covid neurological issues. The first clinic had opened in May, primarily focused on respiratory problems, but both clinics refer patients to other specialists where needed, including cardiologists, physiotherapists and psychiatrists.[64]

On 18 December 2020, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) published a guide to the management of Long COVID.[65]

South Africa

In October 2020, the DATCOV Hospital Surveillance Department of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) looked into a partnership with the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) in order to conduct clinical research into the impact PASC may have within the South African Context. As of the 30th of January 2021, the project has yet to receive ethical approval for the commencement of data collection. Ethics approval was granted on the 3rd of February 2021 and formal data collection began on the 8th of February 2021.

Public response

Some people experiencing long COVID have formed groups on social media sites.[66][67][68][69] There is an active international long COVID patient advocacy movement[70][71] which includes research led by patients themselves.[72][73]

In many of these groups, individuals express frustration and their sense that their problems have been dismissed by medical professionals.[69]

Special populations

Children

A study in Italy, which analyzed 129 children under the age of 18, examined health data obtained via a questionnaire between September 2020 and January 1, 2021. 53% of the group experienced COVID-19 symptoms more than 120 days after their diagnosis. Symptoms included chest tightness and pain, nasal congestion, tiredness, difficulty concentrating and muscle pain. A case report of 5 children in Sweden also reported symptoms (fatigue, heart palpitations, dyspnoea, headaches, muscle weakness and difficulty concentrating) persisting for 6–8 months after diagnosis.[44]

See also

- Post viral cerebellar ataxia – clumsy movement appearing a few weeks after a viral infection

- Post-Ebola virus syndrome – symptoms that persist after recovering from Ebola

- Post-polio syndrome – delayed reaction appearing years after acute polio infection resolves

- COVID-19: neurologic and psychiatric symptoms – both acute and chronic neurologic, psychiatric, olfactory and mental health conditions

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children – pediatric comorbidity from COVID-19

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "COVID-19 and Your Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- 1 2 Oronsky, Bryan; Larson, Christopher; Hammond, Terese C.; Oronsky, Arnold; Kesari, Santosh; Lybeck, Michelle; Reid, Tony R. (20 February 2021). "A Review of Persistent Post-COVID Syndrome (PPCS)". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. doi:10.1007/s12016-021-08848-3. ISSN 1559-0267. PMID 33609255. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Baig AM (October 2020). "Chronic COVID Syndrome: Need for an appropriate medical terminology for Long-COVID and COVID Long-Haulers". Journal of Medical Virology. 93 (5): 2555–2556. doi:10.1002/jmv.26624. PMID 33095459.

- ↑ NICE (18 December 2020). "Overview | COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Healthcare Workers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ "NIH launches new initiative to study "Long COVID"". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 "What doctors wish patients knew about long COVID". American Medical Association. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Healthcare Workers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The prevalence of long COVID symptoms and COVID-19 complications". Office of National Statistics UK. December 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-01-30. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ Di Gennaro, Francesco; Belati, Alessandra; Tulone, Ottavia; Diella, Lucia; Bavaro, Davide Fiore; Bonica, Roberta; Genna, Vincenzo; Smith, Lee; Trott, Mike; Bruyere, Olivier; Mirarchi, Luigi; Cusumano, Claudia; Barbagallo, Mario; Dominguez Rodriguez, Ligia Juliana; Saracino, Annalisa; Veronese, Nicola (4 May 2022). "Long Covid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 120,970 Patients". Social Science Research Network. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ Ledford, Heidi (23 November 2021). "Do vaccines protect against long COVID? What the data say". Nature. pp. 546–548. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03495-2. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ "Center for Post-COVID Care | Mount Sinai - New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Archived from the original on 2022-01-07. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ↑ "Delhi's Post-Covid Clinic For Recovered Patients With Fresh Symptoms Opens". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ Lopez-Leon, Sandra; Wegman-Ostrosky, Talia; Perelman, Carol; Sepulveda, Rosalinda; Rebolledo, Paulina; Cuapio, Angelica; Villapol, Sonia (1 March 2021). "More Than 50 Long-Term Effects of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Research Square. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-266574/v1. PMID 33688642. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Al-Aly, Ziyad; Xie, Yan; Bowe, Benjamin (22 April 2021). "High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequalae of COVID-19". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33887749. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "COVID-19 and Your Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 8 April 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "COVID-19 (coronavirus): Long-term effects". Mayo Clinic. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A'Court C, Buxton M, Husain L (August 2020). "Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care". BMJ. 370: m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026. PMID 32784198. S2CID 221097768. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- 1 2 3 "Living with Covid19. A dynamic review of the evidence around ongoing covid-19 symptoms (often called long covid)". National Institute for Health Research. 15 October 2020. doi:10.3310/themedreview_41169. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2020.

- ↑ Mahase E (October 2020). "Long covid could be four different syndromes, review suggests". BMJ. 371: m3981. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3981. PMID 33055076. S2CID 222348080. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Lay summary in: "Coronavirus: 'Long Covid could be four different syndromes'". BBC News. 15 October 2020.

- ↑ Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ (November 2020). "Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 8 (2): 130–140. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. PMC 7820108. PMID 33181098.

- ↑ Gallagher J (21 October 2020). "Long Covid: Who is more likely to get it?". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ↑ "New research identifies those most at risk from 'long COVID'". King's College London. 21 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, Pujol JC, Klaser K, Antonelli M, Canas LS, Molteni E (19 December 2020). "Attributes and predictors of Long-COVID: analysis of COVID cases and their symptoms collected by the Covid Symptoms Study App". MedRxiv, Preprint Server for the Health Sciences. doi:10.1101/2020.10.19.20214494. S2CID 224805406. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020. Not peer-reviewed as of December 2020

- 1 2 3 4 Brodin, Petter (January 2021). "Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity". Nature Medicine. 27 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-01202-8. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 33442016. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ↑ Graziano, Pinna. "Sex and COVID-19: A Protective Role for Reproductive Steroids". Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ↑ Bjugstad, Kimberly. "Sex Hormones May Be Key Weaponry in the Fight Against COVID-19". Endocrineweb. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ↑ "Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID)". nhs.uk. 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ↑ "Long Covid: what is it and what should you do if you have it". Heart Matters. 16 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ↑ Al-Jahdhami, Issa; Al-Naamani, Khalid; Al-Mawali, Adhra (26 January 2021). "The Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome (Long COVID)". Oman Medical Journal. 36 (1): e220. doi:10.5001/omj.2021.91. ISSN 1999-768X. PMID 33537155. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 "Context | COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- 1 2 "NIH launches new initiative to study "Long COVID"". National Institutes of Health (NIH). February 23, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ↑ Dunham, Jackie (5 May 2021). "Some COVID-19 long-haulers are developing a 'devastating' syndrome". CTV News. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ↑ Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, Rajeev; Sashidharan, S. (2021). "Long COVID: An overview". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 15 (3): 869–875. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007. ISSN 1871-4021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Komaroff A (15 October 2020). "The tragedy of the post-COVID "long haulers"". Harvard Health. Harvard Health Publishing, Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ Nordvig AS, Rimmer KT, Willey JZ, Thakur KT, Boehme AK, Vargas WS, Smith CJ, Elkind MS (2020-06-29). "Potential neurological manifestations of COVID-19". Neurology: Clinical Practice. 11 (2): e135–e146. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000897. ISSN 2163-0402. PMC 8032406. PMID 33842082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC embargo expired (link) - 1 2 Servick K (8 April 2020). "For survivors of severe COVID-19, beating the virus is just the beginning". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc1486. ISSN 0036-8075. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ↑ Tanner C (12 August 2020). "All we know so far about 'long haul' Covid – estimated to affect 600,000 people in the UK". inews. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

i spoke to Professor Tim Spector of King's College London who developed the Covid-19 tracker app

- ↑ Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. (July 31, 2020). "Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (30): 993–998. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. PMC 7392393. PMID 32730238.

- ↑ Tenforde, Mark W.; Kim, Sara S.; Lindsell, Christopher J.; Billig Rose, Erica; Shapiro, Nathan I.; Files, D. Clark; Gibbs, Kevin W.; Erickson, Heidi L.; Steingrub, Jay S.; Smithline, Howard A.; Gong, Michelle N. (2020-07-31). "Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network - United States, March-June 2020". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (30): 993–998. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. ISSN 1545-861X. PMC 7392393. PMID 32730238.

- ↑ Davis, Nicola (16 December 2020). "Long Covid alarm as 21% report symptoms after five weeks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 Herman, Joanna (27 December 2020). "I'm a consultant in infectious diseases. 'Long Covid' is anything but a mild illness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- 1 2 Ludvigsson JF (November 2020). "Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19". Acta Paediatrica. 110 (3): 914–921. doi:10.1111/apa.15673. PMC 7753397. PMID 33205450.

- ↑ Simpson F, Lokugamage A (16 October 2020). "Counting long covid in children". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- 1 2 Fitzgerald B (14 October 2020). "Long-haul COVID-19 patients will need special treatment and extra support, according to new guide for GPs". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ Ross JM, Seiler J, Meisner J, Tolentino L (1 September 2020). "Summary of COVID-19 Long Term Health Effects: Emerging evidence and Ongoing Investigation" (PDF). University of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ↑ "How long does COVID-19 last?". UK COVID Symptom Study. 6 June 2020. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ↑ "Chinese study finds most patients show signs of 'long Covid' six months on". South China Morning Post. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ↑ Huang, Chaolin; Huang, Lixue; et al. (8 January 2021). "6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study". The Lancet. 397 (10270): 220–232. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7833295. PMID 33428867. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ↑ Graham, Edith L.; Clark, Jeffrey R.; Orban, Zachary S.; Lim, Patrick H.; Szymanski, April L.; Taylor, Carolyn; DiBiase, Rebecca M.; Jia, Dan Tong; Balabanov, Roumen; Ho, Sam U.; Batra, Ayush (2021). "Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized Covid-19 "long haulers"". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1002/acn3.51350. ISSN 2328-9503. PMID 33755344. Archived from the original on 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ↑ Belluck, Pam (2021-03-23). "They Had Mild Covid. Then Their Serious Symptoms Kicked In". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ↑ "Chinese study finds most patients show signs of 'long Covid' six months on". South China Morning Post. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ↑ Knapton, Sarah (18 January 2021). "Almost a third of recovered Covid patients return to hospital in five months and one in eight die". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ Salim, Natasya (6 March 2021). "Indonesians open up about the impacts of long COVID, one year since the country's first case". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Perego E, Callard F, Stras L, Melville-Jóhannesson B, Pope R, Alwan NA (1 October 2020). "Why we need to keep using the patient made term "Long Covid"". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ Callard F, Perego E (January 2021). "How and why patients made Long Covid". Social Science & Medicine. 268: 113426. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. PMC 7539940. PMID 33199035.

- ↑ Belluck, Pam (2020-12-04). "Covid Survivors With Long-Term Symptoms Need Urgent Attention, Experts Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ↑ "COVID-19 Neuro Databank-Biobank". NYU Langone Health. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ↑ Cookson C (15 October 2020). "'Long Covid' symptoms can last for months". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh, Trisha (21 September 2020). "Covid-19: An open letter to the UK's chief medical officers". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "NHS to offer 'long covid' sufferers help at specialist centres". NHS England. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "Your COVID Recovery". Your COVID Recovery. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "UCLH opens second 'long Covid' clinic for patients with neurological complications". University College London NHS Foundation Trust. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ "NICE, RCGP and SIGN publish guideline on managing the long-term effects of COVID-19". NICE. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ "Support Group". Body Politic. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ↑ "Long Covid Support Group". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2021-12-17. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ↑ Blazonis, Sarah (27 November 2020). "Facebook Group Created by Tampa Man Aims to Connect COVID-19 Long Haulers". www.baynews9.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- 1 2 Witvliet, Margot Gage (27 November 2020). "Here's how it feels when COVID-19 symptoms last for months". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ Macnamara, Kelly. ""The Covid 'longhaulers' behind a global patient movement"". AFP. Archived from the original on 2021-02-04. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ Sifferlin, Alexandra. ""How Covid-19 Long Haulers Created a Movement"". Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ "Patient-Led Research Patient Led Research Collaborative for Long COVID Long Covid". Patient Led Research Collaborative. Archived from the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ↑ Callard, Felicity; Perego, Elisa (2021-01-01). "How and why patients made Long Covid". Social Science & Medicine. 268: 113426. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. ISSN 0277-9536. PMC 7539940. PMID 33199035.

External links

- Long Covid on YouTube (21 October 2020). – UK Government film about long COVID.

- "PHOSP". Home. University of Leicester. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

The Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) is a consortium of leading researchers and clinicians from across the UK working together to understand and improve long-term health outcomes for patients who have been in hospital with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.