Tremor

| Tremor | |

|---|---|

| |

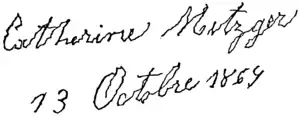

| Writing by a person with Parkinson disease | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurology |

A tremor is an involuntary, somewhat rhythmic, muscle contraction and relaxation involving oscillations or twitching movements of one or more body parts.[1]

It is the most common of all involuntary movements and can affect the hands, arms, eyes, face, head, vocal folds, trunk, and legs. Most tremors occur in the hands. In some people, a tremor is a symptom of another neurological disorder. A very common tremor is the teeth chattering, usually induced by cold temperatures or by fear.

Types

Tremor is most commonly classified by clinical features and cause or origin. Some of the better-known forms of tremor, with their symptoms, include the following:

- Cerebellar tremor (also known as intention tremor) is a slow, broad tremor of the extremities that occurs at the end of a purposeful movement, such as trying to press a button or touching a finger to the tip of one's nose. Cerebellar tremor is caused by lesions in or damage to the cerebellum resulting from stroke, tumor, or disease such as multiple sclerosis or some inherited degenerative disorder. It can also result from chronic alcoholism or overuse of some medicines. In classic cerebellar tremor, a lesion on one side of the brain produces a tremor in that same side of the body that worsens with directed movement. Cerebellar damage can also produce a “wing-beating” type of tremor called rubral or Holmes’ tremor — a combination of rest, action, and postural tremors. The tremor is often most prominent when the affected person is active or is maintaining a particular posture. Cerebellar tremor may be accompanied by other manifestations of ataxia, including dysarthria (speech problems), nystagmus (rapid, involuntary rolling of the eyes), gait problems and postural tremor of the trunk and neck. Titubation is tremor of the head and is of cerebellar origin.

- Dystonic tremor occurs in individuals of all ages who are affected by dystonia, a movement disorder in which sustained involuntary muscle contractions cause twisting and repetitive motions or painful and abnormal postures or positions. Dystonic tremor may affect any muscle in the body and is seen most often when the patient is in a certain position or moves a certain way. The pattern of dystonic tremor may differ from essential tremor. Dystonic tremors occur irregularly and can often be relieved by complete rest. Touching the affected body part or muscle may reduce tremor severity (a geste antagoniste). The tremor may be the initial sign of dystonia localized to a particular part of the body. The dystonic tremor has usually a frequency of about 7 Hz.[2]

- Essential tremor (sometimes inaccurately called benign essential tremor) is the most common of the more than 20 types of tremor. Although the tremor may be mild and nonprogressive in some people, in others, the tremor is slowly progressive, starting on one side of the body but affecting both sides within 3 years. The hands are most often affected but the head, voice, tongue, legs, and trunk may also be involved. Head tremor may be seen as a vertical or horizontal motion. Essential tremor may be accompanied by mild gait disturbance. Tremor frequency may decrease as the person ages, but the severity may increase, affecting the person's ability to perform certain tasks or activities of daily living. Heightened emotion, stress, fever, physical exhaustion, or low blood sugar may trigger tremors or increase their severity. Onset is most common after age 40, although symptoms can appear at any age. It may occur in more than one family member. Children of a parent who has essential tremor have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the condition. Essential tremor is not associated with any known pathology. Its frequency is between 4 and 8 Hz.[2]

- Orthostatic tremor is characterized by fast (>12 Hz) rhythmic muscle contractions that occur in the legs and trunk immediately after standing up. Cramps are felt in the thighs and legs and the patient may shake uncontrollably when asked to stand in one spot. No other clinical signs or symptoms are present and the shaking ceases when the patient sits or is lifted off the ground. The high frequency of the tremor often makes the tremor look like rippling of leg muscles while standing. Orthostatic tremor may also occur in patients who have essential tremor, and there might be an overlap between these categories of tremor.

- Parkinsonian tremor is caused by damage to structures within the brain that control movement. This resting tremor, which can occur as an isolated symptom or be seen in other disorders, is often a precursor to Parkinson's disease (more than 25 percent of patients with Parkinson's disease have an associated action tremor). The tremor, which is classically seen as a "pill-rolling" action of the hands that may also affect the chin, lips, legs, and trunk, can be markedly increased by stress or emotion. Onset is generally after age 60. Movement starts in one limb or on one side of the body and usually progresses to include the other side. The tremor's frequency is between 4 and 6 Hz.[2]

- Physiological tremor occurs in every normal individual and has no clinical significance. It is rarely visible and may be heightened by strong emotion (such as anxiety[3] or fear), physical exhaustion, hypoglycemia, hyperthyroidism, heavy metal poisoning, stimulants, alcohol withdrawal or fever. It can be seen in all voluntary muscle groups and can be detected by extending the arms and placing a piece of paper on top of the hands. Enhanced physiological tremor is a strengthening of physiological tremor to more visible levels. It is generally not caused by a neurological disease but by reaction to certain drugs, alcohol withdrawal, or medical conditions including an overactive thyroid and hypoglycemia. It is usually reversible once the cause is corrected. This tremor classically has a frequency of about 10 Hz.[4]

- Psychogenic tremor (also called hysterical tremor and functional tremor) can occur at rest or during postural or kinetic movement. The characteristics of this kind of tremor may vary but generally include sudden onset and remission, increased incidence with stress, change in tremor direction or body part affected, and greatly decreased or disappearing tremor activity when the patient is distracted. Many patients with psychogenic tremor have a conversion disorder (see Posttraumatic stress disorder) or another psychiatric disease.

- Rubral tremor is characterized by coarse slow tremor which is present at rest, at posture and with intention. This tremor is associated with conditions which affect the red nucleus in the midbrain, classically unusual strokes.

Tremor can result from other conditions as well

- Alcoholism, excessive alcohol consumption, or alcohol withdrawal can kill certain nerve cells, resulting in a tremor known as asterixis. Conversely, small amounts of alcohol may help to decrease familial and essential tremor, but the mechanism behind it is unknown. Alcohol potentiates GABAergic transmission and might act at the level of the inferior olive.

- Tremor in peripheral neuropathy may occur when the nerves that supply the body's muscles are traumatized by injury, disease, abnormality in the central nervous system, or as the result of systemic illnesses. Peripheral neuropathy can affect the whole body or certain areas, such as the hands, and may be progressive. Resulting sensory loss may be seen as a tremor or ataxia (inability to coordinate voluntary muscle movement) of the affected limbs and problems with gait and balance. Clinical characteristics may be similar to those seen in patients with essential tremor.

- Tobacco withdrawal symptoms include tremor.

- Most of the symptoms can also occur randomly when panicked.

Causes

Tremor can be a symptom associated with disorders in those parts of the brain that control muscles throughout the body or in particular areas, such as the hands. Neurological disorders or conditions that can produce tremor include multiple sclerosis, stroke, traumatic brain injury, chronic kidney disease and a number of neurodegenerative diseases that damage or destroy parts of the brainstem or the cerebellum, Parkinson's disease being the one most often associated with tremor. Lesions of the Guillain-Mollaret triangle (also called myoclonic triangle or dentato-rubro-olivary pathway) impair the predictions performed by the cerebellum, causing repetitive muscle discharges by triggering oscillatory activity in the central nervous system.[5] Other causes include the use of drugs (such as amphetamines, cocaine, caffeine, corticosteroids, SSRIs) or alcohol, mercury poisoning, or the withdrawal of drugs such as alcohol or benzodiazepine. Tremors can also be seen in infants with phenylketonuria (PKU), overactive thyroid or liver failure. Tremors can be an indication of hypoglycemia, along with palpitations, sweating and anxiety. Tremor can also be caused by lack of sleep, lack of vitamins, or increased stress.[6][7] Deficiencies of magnesium and thiamine[8] have also been known to cause tremor or shaking, which resolves when the deficiency is corrected.[9] Tremors in animals can also be caused by some spider bites, e.g. the redback spider of Australia.

Diagnosis

During a physical exam, a doctor can determine whether the tremor occurs primarily during action or at rest. The doctor will also check for tremor symmetry, any sensory loss, weakness or muscle atrophy, or decreased reflexes. A detailed family history may indicate if the tremor is inherited. Blood or urine tests can detect thyroid malfunction, other metabolic causes, and abnormal levels of certain chemicals that can cause tremor. These tests may also help to identify contributing causes, such as drug interaction, chronic alcoholism, or another condition or disease. Diagnostic imaging using CT or MRI imaging may help determine if the tremor is the result of a structural defect or degeneration of the brain.

The doctor will perform a neurological examination to assess nerve function and motor and sensory skills. The tests are designed to determine any functional limitations, such as difficulty with handwriting or the ability to hold a utensil or cup. The patient may be asked to place a finger on the tip of her or his nose, draw a spiral, or perform other tasks or exercises.

The doctor may order an electromyogram to diagnose muscle or nerve problems. This test measures involuntary muscle activity and muscle response to nerve stimulation. The selection of the sensors used is important. In addition to studies of muscle activity, tremor can be assessed with accuracy using accelerometers .[10]

Categories

The degree of tremor should be assessed in four positions. The tremor can then be classified by which position most accentuates the tremor:[11]

| Position | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| At rest | Resting tremors | Tremors that are worse at rest include Parkinsonian syndromes and essential tremor if severe. This includes drug-induced tremors from blockers of dopamine receptors such as haloperidol and other antipsychotic drugs. |

| During contraction (e.g. a tight fist while the arm is resting and supported) | Contraction tremors | Tremors that are worse during supported contraction include essential tremor and also cerebellar and exaggerated physiological tremors such as a hyperadrenergic state or hyperthyroidism.[11] Drugs such as adrenergics, anticholinergics, and xanthines (such as caffeine) can exaggerate physiological tremor. |

| During posture (e.g. with the arms elevated against gravity such as in a 'bird-wing' position) | Posture tremors | Tremors that are worse with posture against gravity include essential tremor and exaggerated physiological tremors.[11] |

| During intention (e.g. finger to nose test) | Intention tremors | Intention tremors are tremors that are worse during intention, e.g. as the patient's finger approaches a target, including cerebellar disorders. The terminology of "intention" is currently less used, to the profit of "kinetic". |

Treatment

There is no cure for most tremors. The appropriate treatment depends on accurate diagnosis of the cause. Some tremors respond to treatment of the underlying condition. For example, in some cases of psychogenic tremor, treating the patient's underlying psychological problem may cause the tremor to disappear. A few medications can help relieve symptoms temporarily.

Medications

Medications remain the basis of therapy in many cases. Symptomatic drug therapy is available for several forms of tremor:

- Parkinsonian tremor drug treatment involves L-DOPA or dopamine-like drugs such as pergolide, bromocriptine and ropinirole; They can be dangerous, however, as they may cause symptoms such as tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, clonus, and in rare instances tardive (late developing) psychosis. Other drugs used to lessen parkinsonian tremor include amantadine and anticholinergic drugs like benztropine

- Essential tremor may be treated with beta blockers (such as propranolol and nadolol) or primidone, an anticonvulsant

- Cerebellar tremor symptoms may decrease with the application of alcohol (ethanol) or benzodiazepine medications, both of which carry some risk of dependence or addiction

- Rubral tremor patients may receive some relief using L-DOPA or anticholinergic drugs. Surgery may be helpful

- Dystonic tremor may respond to diazepam, anticholinergic drugs, and intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin. Botulinum toxin is also prescribed to treat voice and head tremors and several movement disorders

- Primary orthostatic tremor sometimes is treated with a combination of diazepam and primidone. Gabapentin provides relief in some cases

- Enhanced physiological tremor is usually reversible once the cause is corrected. If symptomatic treatment is needed, beta blockers can be used

Lifestyle

Eliminating tremor “triggers” such as caffeine and other stimulants from the diet is often recommended. Essential tremor may benefit from slight doses of ethanol, but the potential negative consequences of regular ethanol intake need to be taken into account. Beta blockers have been used as an alternative to alcohol in sports such as competitive dart playing and carry less potential for addiction.

Physical therapy and occupational therapy may help to reduce tremor and improve coordination and muscle control for some patients. A physical therapist or occupational therapist will evaluate the patient for tremor positioning, muscle control, muscle strength, and functional skills. Teaching the patient to brace the affected limb during the tremor or to hold an affected arm close to the body is sometimes useful in gaining motion control. Coordination and balancing exercises may help some patients. Some occupational therapists recommend the use of weights, splints, other adaptive equipment, and special plates and utensils for eating.

Surgery

Surgical intervention such as thalamotomy and deep brain stimulation may ease certain tremors. These surgeries are usually performed only when the tremor is severe and does not respond to drugs. Response can be excellent.

Thalamotomy, involving the creation of lesions in the brain region called the thalamus, is quite effective in treating patients with essential, cerebellar, or Parkinsonian tremor. This in-hospital procedure is performed under local anesthesia, with the patient awake. After the patient's head is secured in a metal frame, the surgeon maps the patient's brain to locate the thalamus. A small hole is drilled through the skull and a temperature-controlled electrode is inserted into the thalamus. A low-frequency current is passed through the electrode to activate the tremor and to confirm proper placement. Once the site has been confirmed, the electrode is heated to create a temporary lesion. Testing is done to examine speech, language, coordination, and tremor activation, if any. If no problems occur, the probe is again heated to create a 3-mm permanent lesion. The probe, when cooled to body temperature, is withdrawn and the skull hole is covered. The lesion causes the tremor to permanently disappear without disrupting sensory or motor control.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) uses implantable electrodes to send high-frequency electrical signals to the thalamus. The electrodes are implanted as described above. The patient uses a hand-held magnet to turn on and turn off a pulse generator that is surgically implanted under the skin. The electrical stimulation temporarily disables the tremor and can be “reversed,” if necessary, by turning off the implanted electrode. Batteries in the generator last about 5 years and can be replaced surgically. DBS is currently used to treat parkinsonian tremor and essential tremor. It is also applied successfully for other rare causes of tremor.

The most common side effects of tremor surgery include dysarthria (problems with motor control of speech), temporary or permanent cognitive impairment (including visual and learning difficulties), and problems with balance.

Biomechanical loading

As well as medication, rehabilitation programmes and surgical interventions, the application of biomechanical loading on tremor movement has been shown to be a technique that is able to suppress the effects of tremor on the human body. It has been established in the literature that most of the different types of tremor respond to biomechanical loading. In particular, it has been clinically tested that the increase of damping or inertia in the upper limb leads to a reduction of the tremorous motion. Biomechanical loading relies on an external device that either passively or actively acts mechanically in parallel to the upper limb to counteract tremor movement. This phenomenon gives rise to the possibility of an orthotic management of tremor.

Starting from this principle, the development of upper-limb non-invasive ambulatory robotic exoskeletons is presented as a promising solution for patients who cannot benefit from medication to suppress the tremor. In this area robotic exoskeletons have emerged, in the form of orthoses, to provide motor assistance and functional compensation to disabled people. An orthosis is a wearable device that acts in parallel to the affected limb. In the case of tremor management, the orthosis must apply a damping or inertial load to a selected set of limb articulations.

Recently, some studies demonstrated that exoskeletons could achieve a consistent 40% of tremor power reduction for all users, being able to attain a reduction ratio in the order of 80% tremor power in specific joints of users with severe tremor.[12] In addition, the users reported that the exoskeleton did not affect their voluntary motion. These results indicate the feasibility of tremor suppression through biomechanical loading.

The main drawbacks of this mechanical management of tremor are (1) the resulting bulky solutions, (2) the inefficiency in transmitting loads from the exoskeleton to the human musculo-skeletal system and (3) technological limitations in terms of actuator technologies. In this regard, current trends in this field are focused on the evaluation of the concept of biomechanical loading of tremor through selective Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) based on a (Brain-to-Computer Interaction) BCI-driven detection of involuntary (tremor) motor activity.[13]

See also

- Cerebral Palsy

- Fasciculation ("at rest" muscle twitches; usually benign).

- Fibrillation

- Restless Leg Syndrome

- Shivering

- Chronic solvent-induced encephalopathy

- Neurology

References

- ↑ Jankovic, Joseph; Lang, Anthony E. (2022). "24. Diagnosis and assessment of Parkinson Disease and other movement disorders; Tremor". In Jankovic, Joseph; Mazziotta, John C.; Pomeroy, Scott L. (eds.). Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. Vol. I. Principles of diagnosis (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. pp. 317–320. ISBN 978-0-323-64261-3. Archived from the original on 2023-07-02. Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- 1 2 3 Chen, Wei; Hopfner, Franziska; Becktepe, Jos Steffen; Deuschl, Günther (2017-06-16). "Rest tremor revisited: Parkinson's disease and other disorders". Translational Neurodegeneration. 6 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/s40035-017-0086-4. ISSN 2047-9158. PMC 5472969. PMID 28638597.

- ↑ Allan H. Goroll; Albert G. Mulley (1 January 2009). Primary care medicine: office evaluation and management of the adult patient. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1178. ISBN 978-0-7817-7513-7. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ Marshall, J.; Walsh, E. G. (1956). "Physiological tremor". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 19 (4): 260–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.19.4.260. PMC 497216. PMID 13377192.

- ↑ Kakei, S; Manto, M; Tanaka, H; Mitoma, H (June 2021). "Pathophysiology of Cerebellar Tremor: The Forward Model-Related Tremor and the Inferior Olive Oscillation-Related Tremor". Front Neurol. 12: 12:694653. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.694653. PMC 8273235. PMID 34262527.

- ↑ Folk, Jim; Folk, Marilyn. "Body Tremors, Shaking, Trembling, Vibrating Anxiety Symptoms". Anxietycentre.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ↑ Sperling Medical Group (27 May 2017). "Lack of Vitamin B12 can cause tremor symptoms". Sperlingmedicalgroup.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ↑ National Research Council. 1996. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, Seventh Revised Ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Soar, J; Perkins, GD; Abbas, G; Alfonzo, A; Barelli, A; Bierens, JJ; Brugger, H; Deakin, CD; Dunning, J; Georgiou, M; Handley, AJ; Lockey, DJ; Paal, P; Sandroni, C; Thies, KC; Zideman, DA; Nolan, JP (October 2010). "European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution". Resuscitation. 81 (10): 1400–33. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.015. PMID 20956045.

- ↑ Grimaldi G, Manto M (2010). "Neurological tremor: sensors, signal processing and emerging applications". Sensors. 10 (2): 1399–1422. Bibcode:2010Senso..10.1399G. doi:10.3390/s100201399. PMC 3244020. PMID 22205874.

- 1 2 3 Jankovic J, Fahn S (September 1980). "Physiologic and pathologic tremors. Diagnosis, mechanism, and management". Ann. Intern. Med. 93 (3): 460–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-460. PMID 7001967.

- ↑ Rocon E, Belda-Lois JM, Ruiz AF, Manto M, Moreno JC, Pons JL (2007). "Design and Validation of a Rehabilitation Robotic Exoskeleton for Tremor Assessment and Suppression" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 15 (3): 367–378. doi:10.1109/tnsre.2007.903917. hdl:10261/24774. PMID 17894269. S2CID 575199. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- ↑ "Tremor project – ICT-2007-224051". Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved Jun 4, 2020.

External links

- "NINDS Tremor Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. July 20, 2007. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-08. Some text copied with permission and thanks.

- Sigvardt, Karen A.; Wheelock, Vicki L.; Kuznetsov, Alexey S.; Rubchinsky, Leonid L. (4 October 2007). "Leonid L. Rubchinsky et al. (2007) Tremor". Scholarpedia. 2 (10): 1379. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.1379. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- orthostatictremor.org Archived 2021-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |