Prasugrel

Prasugrel, sold under the brand name Effient in the US, Australia and India, and Efient in the EU) is a medication used to prevent formation of blood clots. It is a platelet inhibitor and an irreversible antagonist of P2Y12 ADP receptors and is of the thienopyridine drug class. It was developed by Daiichi Sankyo Co. and produced by Ube and marketed in the United States in cooperation with Eli Lilly and Company.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Effient, Efient |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a609027 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ≥79% |

| Protein binding | Active metabolite: ~98% |

| Elimination half-life | ~7 h (range 2 h to 15 h) |

| Excretion | Urine (~68% inactive metabolites); feces (27% inactive metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.228.719 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H20FNO3S |

| Molar mass | 373.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Prasugrel was approved for use in the European Union in February 2009,[1] and in the US in July 2009, for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events (including stent thrombosis) in people with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who are to be managed with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[2]

Medical uses

Prasugrel is used in combination with low dose aspirin to prevent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome, including unstable angina pectoris, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), who are planned for treatment with PCI. Prasugrel is associated with a higher bleeding risk compared to clopidogrel but has demonstrated superiority in reducing the composite endpoint of death, recurrent myocardial infarctions and stroke.[3]

Prasugrel does not change the risk of death when given to people who have had a STEMI or NSTEMI.

Given the risk of bleeding, prasugrel should not be used in people who are older than 75 years, who have low body weight or a history of transient ischemic attacks or strokes.[3][4] The initiation of prasugrel before coronary angiography outside the context of primary PCI is not recommended.[5][6][4]

Approval status

The drug was introduced to clinical practice in Canada in 2010 [7] but was subsequently withdrawn by the manufacturer in 2020 as a "business decision". This has left a gap in the management of high-risk patients in certain situations in Canada where Effient was the drug of choice.[8]

Contraindications

Prasugrel should not be given to people with active pathological bleeding, such as peptic ulcer or a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke, because of higher risk of stroke (thrombotic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage).[9]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects include:[10]

- Cardiovascular: Hypertension (8%), hypotension (4%), atrial fibrillation (3%), bradycardia (3%), noncardiac chest pain (3%), peripheral edema (3%), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- Central nervous system: Headache (6%), dizziness (4%), fatigue (4%), fever (3%), extremity pain (3%)

- Dermatologic: Rash (3%)

- Endocrine and metabolic: Hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia (7%)

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea (5%), diarrhea (2%), gastrointestinal hemorrhage (2%)

- Hematologic: Leukopenia (3%), anemia (2%)

- Neuromuscular and skeletal: Back pain (5%)

- Respiratory: Epistaxis (6%), dyspnea (5%), cough (4%)

- Hypersensitivity, including angioedema

Interactions

Prasugrel has a low potential for interactions. It may, for example, be used with proton pump inhibitors to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding without loss of its antiplatelet effect.[11][12][13][14]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Prasugrel is a member of the thienopyridine class of ADP receptor inhibitors, like ticlopidine (trade name Ticlid) and clopidogrel (trade name Plavix). These agents reduce the aggregation ("clumping") of platelets by irreversibly binding to P2Y12 receptors. Prasugrel inhibits platelet aggregation more rapidly, more consistently, and to a greater extent than clopidogrel.

[15][16] The TRITON-TIMI 38 study compared prasugrel with clopidogrel, and showed that prasugrel reduced rates of ischaemic events, but increased bleeding risk. Overall mortality rates were similar for each drug.[17]

Clopidogrel, unlike prasugrel, was issued a black box warning from the FDA on March 12, 2010, as the estimated 2–14% of the US population who have low levels of the CYP2C19 liver enzyme needed to activate clopidogrel may not get the full effect. Tests are available to predict if a patient would be susceptible to this problem or not.[18][19] Unlike clopidogrel, prasugrel is effective in most individual with the exception in patients over the age of 75, weight under 60 kg, and patients with a history of stroke or TIA due to increased risk of bleeding,[20][21] although several cases have been reported of decreased responsiveness to prasugrel.[22] It has been suggested that the decreased responsiveness observed in prasugrel is likely due to its low but significant frequency of High Platelet Reactivity (HPR).[23]

Pharmacodynamics

Prasugrel produces inhibition of platelet aggregation to 20 μM or 5 μM ADP, as measured by light transmission aggregometry.[24] Following a 60-mg loading dose of the drug, about 90% of patients had at least 50% inhibition of platelet aggregation by one hour. Maximum platelet inhibition was about 80%. Mean steady-state inhibition of platelet aggregation was about 70% following three to five days of dosing at 10 mg daily after a 60-mg loading dose. Platelet aggregation gradually returns to baseline values over five to 9 days after discontinuation of prasugrel, this time course being a reflection of new platelet production rather than pharmacokinetics of prasugrel. Discontinuing clopidogrel 75 mg and initiating prasugrel 10 mg with the next dose resulted in increased inhibition of platelet aggregation, but not greater than that typically produced by a 10-mg maintenance dose of prasugrel alone. Increasing platelet inhibition could increase bleeding risk. The relationship between inhibition of platelet aggregation and clinical activity has not been established.[10]

Pharmacokinetics

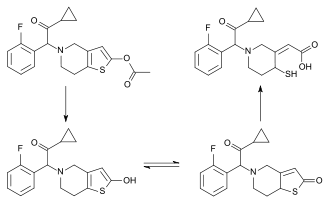

Prasugrel is a prodrug and is rapidly metabolized by carboxylesterase 2 in the intestine and carboxylesterase 1 in the liver to a likewise inactive thiolactone, which is then converted by CYP3A4 and CYP2B6, and to a minor extent by CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, to a pharmacologically active metabolite (R-138727).[25][26] R-138727 has an elimination half-life of about 7 hours (range 2 h to 15 h). Healthy subjects, patients with stable atherosclerosis, and patients undergoing PCI show similar pharmacokinetics.

Chemistry

Prasugrel has one chiral atom. It is used in racemic form as the hydrochloride salt, which is a white powder.

References

- "European Public Assessment Report for Efient" (PDF). EMA. 2009.

- Baker WL, White CM (2009). "Role of prasugrel, a novel P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, in the management of acute coronary syndromes". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 9 (4): 213–29. doi:10.2165/1131209-000000000-00000. PMID 19655817. S2CID 37160513.

- Wiviott, Stephen D.; Braunwald, Eugene; McCabe, Carolyn H.; Montalescot, Gilles; Ruzyllo, Witold; Gottlieb, Shmuel; Neumann, Franz-Joseph; Ardissino, Diego; De Servi, Stefano; Murphy, Sabina A.; Riesmeyer, Jeffrey; Weerakkody, Govinda; Gibson, C. Michael; Antman, Elliott M. (15 November 2007). "Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (20): 2001–2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. PMID 17982182.

- Chew, Derek P; Scott, Ian A; Cullen, Louise; French, John K; Briffa, Tom G; Tideman, Philip A; Woodruffe, Stephen; Kerr, Alistair; Branagan, Maree; Aylward, Philip EG (August 2016). "National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2016". Medical Journal of Australia. 205 (3): 128–133. doi:10.5694/mja16.00368. PMID 27465769. S2CID 13014429.

- Bellemain-Appaix, A.; Kerneis, M.; O'Connor, S. A.; Silvain, J.; Cucherat, M.; Beygui, F.; Barthelemy, O.; Collet, J.-P.; Jacq, L.; Bernasconi, F.; Montalescot, G. (24 October 2014). "Reappraisal of thienopyridine pretreatment in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 347 (aug06 2): g6269. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6269. PMC 4208629. PMID 25954988.

- Montalescot, Gilles; Bolognese, Leonardo; Dudek, Dariusz; Goldstein, Patrick; Hamm, Christian; Tanguay, Jean-Francois; ten Berg, Jurrien M.; Miller, Debra L.; Costigan, Timothy M.; Goedicke, Jochen; Silvain, Johanne; Angioli, Paolo; Legutko, Jacek; Niethammer, Margit; Motovska, Zuzana; Jakubowski, Joseph A.; Cayla, Guillaume; Visconti, Luigi Oltrona; Vicaut, Eric; Widimsky, Petr (12 September 2013). "Pretreatment with Prasugrel in Non–ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (11): 999–1010. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308075. PMID 23991622.

- "Product information -Effient". Health Canada. 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- Lordkipanidzé, Marie; et al. (December 2020). "Implications of the Antiplatelet Therapy Gap Left with Discontinuation of Prasugrel in Canada". CJC Open. 2020 (6): 814–821. doi:10.1016/j.cjco.2020.11.021. ISSN 2589-790X. PMC 8209390. PMID 34169260.

- "Effient (prasugrel hydrochloride) Prescribing Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). September 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- Efient: Highlights of prescribing information

- John J, Koshy SK (2012). "Current oral antiplatelets: focus update on prasugrel". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 25 (3): 343–9. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.100270. PMID 22570398.

- Demcsák A, Lantos T, Bálint ER, Hartmann P, Vincze Á, Bajor J, et al. (2018-11-19). "PPIs Are Not Responsible for Elevating Cardiovascular Risk in Patients on Clopidogrel-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Physiology. 9: 1550. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01550. PMC 6252380. PMID 30510515.

- O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, et al. (September 2009). "Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials". Lancet. 374 (9694): 989–997. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. PMID 19726078. S2CID 205956050.

- Vaduganathan M, Cannon CP, Cryer BL, Liu Y, Hsieh WH, Doros G, et al. (September 2016). "Efficacy and Safety of Proton-Pump Inhibitors in High-Risk Cardiovascular Subsets of the COGENT Trial". The American Journal of Medicine. 129 (9): 1002–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.042. PMID 27143321.

- Brandt JT, Payne CD, Wiviott SD, Weerakkody G, Farid NA, Small DS, et al. (January 2007). "A comparison of prasugrel and clopidogrel loading doses on platelet function: magnitude of platelet inhibition is related to active metabolite formation". American Heart Journal. 153 (1): 66.e9–16. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.010. PMID 17174640.

- Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, O'Donoghue M, Neumann FJ, Michelson AD, et al. (December 2007). "Prasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the Prasugrel in Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 44 trial". Circulation. 116 (25): 2923–32. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740324. PMID 18056526.

- Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. (November 2007). "Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (20): 2001–15. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. PMID 17982182.

- "FDA Announces New Boxed Warning on Plavix: Alerts patients, health care professionals to potential for reduced effectiveness" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 12, 2010. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 12, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- Ruff, Christian T.; Giugliano, Robert P.; Antman, Elliott M.; Murphy, Sabina A.; Lotan, Chaim; Heuer, Herbertus; Merkely, Bela; Baracioli, Luciano; Schersten, Fredrik; Seabro-Gomes, Ricardo; Braunwald, Eugene (March 2012). "Safety and efficacy of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in different regions of the world". International Journal of Cardiology. 155 (3): 424–429. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.040. ISSN 0167-5273. PMID 21093072.

- Wiviott, Stephen D.; Braunwald, Eugene; McCabe, Carolyn H.; Montalescot, Gilles; Ruzyllo, Witold; Gottlieb, Shmuel; Neumann, Franz-Joseph; Ardissino, Diego; De Servi, Stefano; Murphy, Sabina A.; Riesmeyer, Jeffrey (2007-11-15). "Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (20): 2001–2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 17982182.

- Silvano M, Zambon CF, De Rosa G, Plebani M, Pengo V, Napodano M, Padrini R (February 2011). "A case of resistance to clopidogrel and prasugrel after percutaneous coronary angioplasty". Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 31 (2): 233–4. doi:10.1007/s11239-010-0533-x. PMID 21088983. S2CID 20617890.

- Warlo, Ellen M. K.; Arnesen, Harald; Seljeflot, Ingebjørg (December 2019). "A brief review on resistance to P2Y12 receptor antagonism in coronary artery disease". Thrombosis Journal. 17 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s12959-019-0197-5. ISSN 1477-9560. PMC 6558673. PMID 31198410.

- O'Riordan, Michael. "Switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel further reduces platelet function". TheHeart.org. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- Rehmel JL, Eckstein JA, Farid NA, Heim JB, Kasper SC, Kurihara A, et al. (April 2006). "Interactions of two major metabolites of prasugrel, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, with the cytochromes P450". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 34 (4): 600–7. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.007989. PMID 16415119. S2CID 1698598.

- Kurokawa T, Fukami T, Yoshida T, Nakajima M (March 2016). "Arylacetamide Deacetylase is Responsible for Activation of Prasugrel in Human and Dog". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 44 (3): 409–16. doi:10.1124/dmd.115.068221. PMID 26718653.

Further reading

- Dean L (2017). "Prasugrel Therapy and CYP Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520385. Bookshelf ID: NBK425796.

External links

- "Prasugrel". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- US 5288726 claims prasugrel compound; expired on 14 April 2017

- US 6693115 claims hydrochloride salt of prasugrel; will expire on 3 July 2021