Ricin

Ricin (/ˈraɪsɪn/ RY-sin) is a lectin (a carbohydrate-binding protein) and a highly potent toxin produced in the seeds of the castor oil plant, Ricinus communis. The median lethal dose (LD50) of ricin for mice is around 22 micrograms per kilogram of body weight via intraperitoneal injection. Oral exposure to ricin is far less toxic. An estimated lethal oral dose in humans is approximately 1 milligram per kilogram of body weight.[1]

| Ricin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ricin structure (PDB: 2AAI). The A chain is shown in blue and the B chain in orange. | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | RCOM_2159910 | ||||||

| Entrez | 8287993 | ||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | XM_002534603.1 | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | XP_002534649.1 | ||||||

| UniProt | P02879 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 3.2.2.22 | ||||||

| Chromosome | whole genome: 0 - 0.01 Mb | ||||||

| |||||||

| Ribosome-inactivating protein (Ricin A chain) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | RIP | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00161 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001574 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00248 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1paf / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Ricin-type beta-trefoil lectin domain (Ricin B chain) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | N/A | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00652 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0066 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | IPR000772 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1abr / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| CAZy | CBM13 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd00161 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Ricin was first described by Peter Hermann Stillmark, the founder of lectinology.

Biochemistry

Ricin is classified as a type 2 ribosome-inactivating protein (RIP). Whereas type 1 RIPs are composed of a single protein chain that possesses catalytic activity, type 2 RIPs, also known as holotoxins, are composed of two different protein chains that form a heterodimeric complex. Type 2 RIPs consist of an A chain that is functionally equivalent to a type 1 RIP, covalently connected by a single disulfide bond to a B chain that is catalytically inactive, but serves to mediate transport of the A-B protein complex from the cell surface, via vesicle carriers, to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Both type 1 and type 2 RIPs are functionally active against ribosomes in vitro; however, only type 2 RIPs display cytotoxicity due to the lectin-like properties of the B chain. To display its ribosome-inactivating function, the ricin disulfide bond must be reductively cleaved.[2]

Biosynthesis

Ricin is synthesized in the endosperm of castor oil plant seeds.[3] The ricin precursor protein is 576 amino acid residues in length and contains a signal peptide (residues 1–35), the ricin A chain (36–302), a linker peptide (303–314), and the ricin B chain (315–576).[4] The N-terminal signal sequence delivers the prepropolypeptide to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and then the signal peptide is cleaved off. Within the lumen of the ER the propolypeptide is glycosylated and a protein disulfide isomerase catalyzes disulfide bond formation between cysteines 294 and 318. The propolypeptide is further glycosylated within the Golgi apparatus and transported to protein storage bodies. The propolypeptide is cleaved within protein bodies by an endopeptidase to produce the mature ricin protein that is composed of a 267 residue A chain and a 262 residue B chain that are covalently linked by a single disulfide bond.[3]

Structure

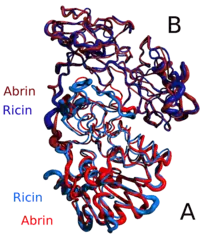

In terms of structure, ricin closely resembles abrin-a, an isotoxin of abrin. The quaternary structure of ricin is a globular, glycosylated heterodimer of approximately 60–65 kDa.[5] Ricin toxin A chain and ricin toxin B chain are of similar molecular weights, approximately 32 kDa and 34 kDa, respectively.

- Ricin toxin A chain (RTA) is an N-glycoside hydrolase composed of 267 amino acids.[6] It has three structural domains with approximately 50% of the polypeptide arranged into alpha-helices and beta-sheets.[7] The three domains form a pronounced cleft that is the active site of RTA.

- Ricin toxin B chain (RTB) is a lectin composed of 262 amino acids that is able to bind terminal galactose residues on cell surfaces.[8] RTB forms a bilobal, barbell-like structure lacking alpha-helices or beta-sheets where individual lobes contain three subdomains. At least one of these three subdomains in each homologous lobe possesses a sugar-binding pocket that gives RTB its functional character.

While other plants contain the protein chains found in ricin, both protein chains must be present to produce toxic effects. For example, plants that contain only protein chain A, such as barley, are not toxic because without the link to protein chain B, protein chain A cannot enter the cell and do damage to ribosomes.[9]

Entry into the cytoplasm

Ricin B chain binds complex carbohydrates on the surface of eukaryotic cells containing either terminal N-acetylgalactosamine or beta-1,4-linked galactose residues. In addition, the mannose-type glycans of ricin are able to bind to cells that express mannose receptors.[10] RTB has been shown to bind to the cell surface on the order of 106–108 ricin molecules per cell surface.[11]

The profuse binding of ricin to surface membranes allows internalization with all types of membrane invaginations. The holotoxin can be taken up by clathrin-coated pits, as well as by clathrin-independent pathways including caveolae and macropinocytosis.[12][13] Intracellular vesicles shuttle ricin to endosomes that are delivered to the Golgi apparatus. The active acidification of endosomes is thought to have little effect on the functional properties of ricin. Because ricin is stable over a wide pH range, degradation in endosomes or lysosomes offers little or no protection against ricin.[14] Ricin molecules are thought to follow retrograde transport via early endosomes, the trans-Golgi network, and the Golgi to enter the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).[15]

For ricin to function cytotoxically, RTA must be reductively cleaved from RTB to release a steric block of the RTA active site. This process is catalysed by the protein PDI (protein disulphide isomerase) that resides in the lumen of the ER.[16][17] Free RTA in the ER lumen then partially unfolds and partially buries into the ER membrane, where it is thought to mimic a misfolded membrane-associated protein.[18] Roles for the ER chaperones GRP94,[19] EDEM[20] and BiP[21] have been proposed prior to the 'dislocation' of RTA from the ER lumen to the cytosol in a manner that uses components of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway. ERAD normally removes misfolded ER proteins to the cytosol for their destruction by cytosolic proteasomes. Dislocation of RTA requires ER membrane-integral E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes,[22] but RTA avoids the ubiquitination that usually occurs with ERAD substrates because of its low content of lysine residues, which are the usual attachment sites for ubiquitin.[23] Thus, RTA avoids the usual fate of dislocated proteins (destruction that is mediated by targeting ubiquitinylated proteins to the cytosolic proteasomes). In the mammalian cell cytosol, RTA then undergoes triage by the cytosolic molecular chaperones Hsc70 and Hsp90 and their co-chaperones, as well as by one subunit (RPT5) of the proteasome itself, that results in its folding to a catalytic conformation,[19][24] which de-purinates ribosomes, thus halting protein synthesis.

Ribosome inactivation

RTA has rRNA N-glycosylase activity that is responsible for the cleavage of a glycosidic bond within the large rRNA of the 60S subunit of eukaryotic ribosomes.[25] RTA specifically and irreversibly hydrolyses the N-glycosidic bond of the adenine residue at position 4324 (A4324) within the 28S rRNA, but leaves the phosphodiester backbone of the RNA intact.[26] The ricin targets A4324 that is contained in a highly conserved sequence of 12 nucleotides universally found in eukaryotic ribosomes. The sequence, 5'-AGUACGAGAGGA-3', termed the sarcin-ricin loop, is important in binding elongation factors during protein synthesis.[27] The depurination event rapidly and completely inactivates the ribosome, resulting in toxicity from inhibited protein synthesis. A single RTA molecule in the cytosol is capable of depurinating approximately 1500 ribosomes per minute.

Depurination reaction

Within the active site of RTA, there exist several invariant amino acid residues involved in the depurination of ribosomal RNA.[14] Although the exact mechanism of the event is unknown, key amino acid residues identified include tyrosine at positions 80 and 123, glutamic acid at position 177, and arginine at position 180. In particular, Arg180 and Glu177 have been shown to be involved in the catalytic mechanism, and not substrate binding, with enzyme kinetic studies involving RTA mutants. The model proposed by Mozingo and Robertus,[7] based on X-ray structures, is as follows:

- Sarcin-ricin loop substrate binds RTA active site with target adenine stacking against tyr80 and tyr123.

- Arg180 is positioned such that it can protonate N-3 of adenine and break the bond between N-9 of the adenine ring and C-1' of the ribose.

- Bond cleavage results in an oxycarbonium ion on the ribose, stabilized by Glu177.

- N-3 protonation of adenine by Arg180 allows deprotonation of a nearby water molecule.

- Resulting hydroxyl attacks ribose carbonium ion.

- Depurination of adenine results in a neutral ribose on an intact phosphodiester RNA backbone.

Toxicity

Ricin is very toxic if inhaled, injected, or ingested. It can also be toxic if dust contacts the eyes or if it is absorbed through damaged skin. It acts as a toxin by inhibiting protein synthesis.[28][29] It prevents cells from assembling various amino acids into proteins according to the messages it receives from messenger RNA in a process conducted by the cell's ribosome (the protein-making machinery) – that is, the most basic level of cell metabolism, essential to all living cells and thus to life itself. Ricin is resistant, but not impervious, to digestion by peptidases. By ingestion, the pathology of ricin is largely restricted to the gastrointestinal tract, where it may cause mucosal injuries. With appropriate treatment, most patients will make a good recovery.[30][31]

Symptoms

Because the symptoms are caused by failure to make protein, they may take anywhere from hours to days to appear, depending on the route of exposure and the dose. When ingested, gastrointestinal symptoms can manifest within six hours; these symptoms do not always become apparent. Within two to five days of exposure to ricin, its effects on the central nervous system, adrenal glands, kidneys, and liver appear.[29]

Ingestion of ricin causes pain, inflammation, and hemorrhage in the mucosal membranes of the gastrointestinal system. Gastrointestinal symptoms quickly progress to severe nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). Haemorrhage causes bloody feces (melena) and vomiting blood (hematemesis). The low blood volume (hypovolemia) caused by gastrointestinal fluid loss can lead to organ failure in the pancreas, kidney, liver, and GI tract and progress to shock. Shock and organ failure are indicated by disorientation, stupor, weakness, drowsiness, excessive thirst (polydipsia), low urine production (oliguria), and bloody urine (hematuria).[29]

Symptoms of ricin inhalation are different from those caused by ingestion. Early symptoms include a cough and fever.[29]

When skin or inhalation exposure occur, ricin can cause an allergy to develop. This is indicated by swelling (edema) of the eyes and lips; asthma; bronchial irritation; dry, sore throat; congestion; skin redness (erythema); skin blisters (vesication); wheezing; itchy, watery eyes; chest tightness; and skin irritation.[29]

Treatment

An antidote has been developed by the UK military, although as of 2006 it has not yet been tested on humans.[32][33] As of 2005 another antidote developed by the US military has been shown to be safe and effective in lab mice injected with antibody-rich blood mixed with ricin, and has had some human testing.[34]

Symptomatic and supportive treatments are available for ricin poisoning. Existing treatments emphasize minimizing the effects of the poison. Possible treatments include intravenous fluids or electrolytes, airway management, assisted ventilation, or giving medications to remedy seizures and low blood pressure. If the ricin has been ingested recently, the stomach can be flushed by ingesting activated charcoal or by performing gastric lavage. Survivors often develop long-term organ damage. Ricin causes severe diarrhea and vomiting, and victims can die of circulatory shock or organ failure; inhaled ricin can cause fatal pulmonary edema or respiratory failure. Death typically occurs within 3–5 days of exposure.[29]

Prevention

Vaccination is possible by injecting an inactive form of protein chain A.[9] This vaccination is effective for several months due to the body's production of antibodies to the foreign protein. In 1978 Bulgarian defector Vladimir Kostov survived a ricin attack similar to the one on Georgi Markov, probably due to his body's production of antibodies. When a ricin-laced pellet was removed from the small of his back it was found that some of the original wax coating was still attached. For this reason only small amounts of ricin had leaked out of the pellet, producing some symptoms but allowing his body to develop immunity to further poisoning.[9]

Sources

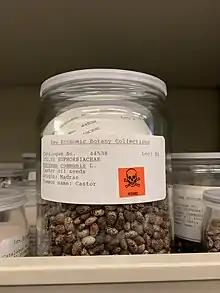

The seeds of Ricinus communis are commonly crushed to extract castor oil. As ricin is not oil-soluble, little is found in the extracted castor oil.[9] The extracted oil is also heated to more than 80 °C (176 °F) to denature any ricin that may be present.[9] The remaining spent crushed seeds, called variously the "cake", "oil cake", and "press cake", can contain up to 5% ricin.[35] While the oil cake from coconut, peanuts, and sometimes cotton seeds can be used as cattle feed or fertilizer, the toxic nature of castor beans precludes their oil cake from being used as feed unless the ricin is first deactivated by autoclaving.[36] Accidental ingestion of Ricinus communis cake intended for fertilizer has been reported to be responsible for fatal ricin poisoning in animals.[28][37]

Deaths from ingesting castor plant seeds are rare, partly because of their indigestible seed coat, and because some of the ricin is deactivated in the stomach.[5] The pulp from eight beans is considered dangerous to an adult.[38] Rauber and Heard have written that close examination of early 20th century case reports indicates that public and professional perceptions of ricin toxicity "do not accurately reflect the capabilities of modern medical management".[39]

Most acute poisoning episodes in humans are the result of oral ingestion of castor beans, 5–20 of which could prove fatal to an adult. Swallowing castor beans rarely proves to be fatal unless the bean is thoroughly chewed. The survival rate of castor bean ingestion is 98%.[9] In 2013 a 37-year-old woman in the United States survived after ingesting 30 beans.[40] Victims often manifest nausea, diarrhea, fast heart rate, low blood pressure, and seizures persisting for up to a week.[28] Blood, plasma, or urine ricin or ricinine concentrations may be measured to confirm diagnosis. The laboratory testing usually involves immunoassay or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.[41]

Therapeutic applications

Although no approved therapeutics are currently based on ricin, it does have the potential to be used in the treatment of tumors, as a "magic bullet" to destroy targeted cells.[14] Because ricin is a protein, it can be linked to a monoclonal antibody to target cancerous cells recognized by the antibody. The major problem with ricin is that its native internalization sequences are distributed throughout the protein. If any of these native internalization sequences are present in a therapeutic agent, the drug will be internalized by, and kill, untargeted non-tumorous cells as well as targeted cancerous cells.

Modifying ricin may sufficiently lessen the likelihood that the ricin component of these immunotoxins will cause the wrong cells to internalize it, while still retaining its cell-killing activity when it is internalized by the targeted cells. However, bacterial toxins, such as diphtheria toxin, which is used in denileukin diftitox, an FDA-approved treatment for leukemia and lymphoma, have proven to be more practical. A promising approach for ricin is to use the non-toxic B subunit (a lectin) as a vehicle for delivering antigens into cells, thus greatly increasing their immunogenicity. Use of ricin as an adjuvant has potential implications for developing mucosal vaccines.

Regulation

In the US, ricin appears on the select agents list of the Department of Health and Human Services,[42] and scientists must register with HHS to use ricin in their research. However, investigators possessing less than 1000 mg (1 g) are exempt from regulation.[43]

Ricin is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the US Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities that produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[44]

Chemical or biological warfare agent

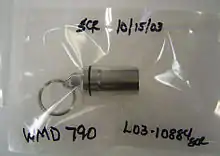

The United States investigated ricin for its military potential during World War I.[45] At that time it was being considered for use either as a toxic dust or as a coating for bullets and shrapnel. The dust cloud concept could not be adequately developed, and the coated bullet/shrapnel concept would violate the Hague Convention of 1899 (adopted in U.S. law at 32 Stat. 1903), specifically Annex §2, Ch.1, Article 23, stating "... it is especially prohibited ... [t]o employ poison or poisoned arms".[46] World War I ended before the United States weaponized ricin.

During World War II the United States and Canada undertook studying ricin in cluster bombs.[47] Though there were plans for mass production and several field trials with different bomblet concepts, the end conclusion was that it was no more economical than using phosgene. This conclusion was based on comparison of the final weapons, rather than ricin's toxicity (LCt50 ~10 mg/min·m3). Ricin was given the military symbol W or later WA. Interest in it continued for a short period after World War II, but soon subsided when the US Army Chemical Corps began a program to weaponize sarin.[48]

The Soviet Union also possessed weaponized ricin. The KGB developed weapons using ricin which were used outside the Soviet bloc, most famously in the Markov assassination.[49][50]

In spite of ricin's extreme toxicity and utility as an agent of chemical/biological warfare, production of the toxin is difficult to limit. The castor bean plant from which ricin is derived is a common ornamental and can be grown at home without any special care.

Under both the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention and the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention, ricin is listed as a schedule 1 controlled substance. Despite this, more than 1 million metric tons (1,100,000 short tons) of castor beans are processed each year, and approximately 5% of the total is rendered into a waste containing negligible concentrations of undenatured ricin toxin.[51]

Ricin is several orders of magnitude less toxic than botulinum or tetanus toxin, but the latter are harder to come by. Compared to botulinum or anthrax as biological weapons or chemical weapons, the quantity of ricin required to achieve LD50 over a large geographic area is significantly more than an agent such as anthrax (tons of ricin vs. only kilogram quantities of anthrax).[52] Ricin is easy to produce, but is not as practical or likely to cause as many casualties as other agents.[30] Ricin is easily denatured by temperatures over 80 °C (176 °F) meaning many methods of deploying ricin would generate enough heat to denature it.[35] Once deployed, an area contaminated with ricin remains dangerous until the bonds between chain A or B have been broken, a process that takes two or three days.[9] In contrast, anthrax spores may remain lethal for decades. Jan van Aken, a German expert on biological weapons, explained in a report for The Sunshine Project that Al Qaeda's experiments with ricin suggest their inability to produce botulinum or anthrax.[53]

Developments

A biopharmaceutical company called Soligenix, Inc. licensed an anti-ricin vaccine called RiVax from Vitetta et al. at UT Southwestern. The vaccine was found safe and immunogenic in mice, rabbits, and humans. Two successful clinical trials were completed.[54] Soligenix was issued a US patent for Rivax. The ricin vaccine candidate was granted orphan drug status in the US and the EEC and, as of 2019, was in clinical trials in the US. Grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the US Food and Drug Administration supported development of the vaccine candidate.[55]

Synthesis

The first isolation of ricin is attributed to the Baltic-German microbiologist Peter Hermann Stillmark (1860–1923) in 1888.[56][57][58]

Incidents

Ricin has been involved in a number of incidents. In 1978, the Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov was assassinated by Bulgarian secret police who surreptitiously shot him on a London street with a modified umbrella using compressed gas to fire a tiny pellet contaminated with ricin into his leg.[30][59] He died in a hospital a few days later and his body was passed to a special poison branch of the British Ministry of Defence that discovered the pellet during an autopsy. The prime suspects were the Bulgarian secret police: Georgi Markov had defected from Bulgaria some years previously and had subsequently written books and made radio broadcasts that were highly critical of the Bulgarian communist regime. However, it was believed at the time that Bulgaria would not have been able to produce the pellet, and it was also believed that the KGB had supplied it. The KGB denied any involvement, although high-profile KGB defectors Oleg Kalugin and Oleg Gordievsky have since confirmed the KGB's involvement. Earlier, Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn also had (but survived) ricin-like symptoms after an encounter in 1971 with KGB agents.[60]

Ten days before the attack on Georgi Markov another Bulgarian defector, Vladimir Kostov, survived a similar attack. Kostov was standing on an escalator of the Paris metro when he felt a sting in his lower back above the belt of his trousers. He developed a fever, but recovered. After Markov's death the wound on Kostov's back was examined and a ricin-laced pellet identical to the one used against Markov was removed.[9]

Several terrorists and terrorist groups have experimented with ricin and caused several incidents of the poisons being mailed to US politicians. For example, on 29 May 2013 two anonymous letters sent to New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg contained traces of it.[61] Another was sent to the offices of Mayors Against Illegal Guns in Washington, D.C. A letter containing ricin was also alleged to have been sent to American President Barack Obama at the same time. An actress, Shannon Richardson, was later charged with the crime, to which she pleaded guilty that December.[62] On 16 July 2014, Richardson was sentenced to 18 years in prison plus a restitution fine of $367,000.[63] On 2 October 2018, two letters suspected of containing ricin were sent to The Pentagon; one addressed to Secretary of Defense James Mattis, and the other to Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John Richardson.[64] A letter was received on 23 July 2019 at Pelican Bay State Prison in California which claimed to contain a suspicious substance. Authorities later confirmed it contained ricin; no detrimental exposures were identified.[65]

In 2020, some media in the Czech Republic reported (based on intelligence information) that a person carrying a Russian diplomatic passport and ricin had arrived in Prague with an intention to assassinate three politicians, however Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia, called it fake. The targets would have been: first, Zdeněk Hřib, the mayor of Prague (capital of the Czech Republic), who was involved in renaming a square in Prague, "Pod Kaštany", where the Russian embassy is situated, to the Square of Boris Nemtsov, an opposition politician assassinated in the Kremlin in 2015. Second, Ondřej Kolář, the mayor of Prague 6 municipal district, who was involved in removing the controversial statue to the Soviet-era Marshal Konev. Third, Pavel Novotný, the mayor of Prague's southwestern Řeporyje district. All of these three politicians had received police protection.[66][67] Later, the Czech president Miloš Zeman claimed that the police protection of Zdeněk Hřib is a publicity stunt. Zeman also confused ricin with castor oil and claimed that ricin is a non-poisonous laxative.[68]

In popular culture

Ricin has been used as a plot device, such as in the television series Breaking Bad.[69]

The popularity of Breaking Bad inspired several real-life criminal cases involving ricin or similar substances. Kuntal Patel from London attempted to poison her mother with abrin after the latter interfered with her marriage plans.[70] Daniel Milzman, a 19-year-old former Georgetown University student, was charged with manufacturing ricin in his dorm room, as well as the intent of "[using] the ricin on another undergraduate student with whom he had a relationship".[71] Mohammed Ali from Liverpool, England, was convicted after attempting to purchase 500 mg of ricin over the dark web from an undercover FBI agent. He was sentenced, on 18 September 2015, to eight years imprisonment.[72]

In the 2013 movie The Good Mother, antagonist Cheryl Jordan injects her daughters with ricin and puts ricin in their food in order to poison them in a case of Munchausen by proxy. She is eventually caught after one daughter dies.

See also

- Viscum album (European mistletoe)

References

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (September 2008). "Ricin (from Ricinus communis) as undesirable substances in animal feed‐Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain". EFSA Journal. 6 (9): 726. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2008.726.

- Wright HT, Robertus JD (July 1987). "The intersubunit disulfide bridge of ricin is essential for cytotoxicity". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 256 (1): 280–284. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(87)90447-4. PMID 3606124.

- Lord MJ, Roberts LM (2005). "Ricin: structure, synthesis, and mode of action". In Raffael S, Schmitt M (eds.). Microbial Protein Toxins. Topics in Current Genetics. Vol. 11. Berlin: Springer. pp. 215–233. doi:10.1007/b100198. ISBN 978-3-540-23562-0.

- "P02879 Ricin precursor – Ricinus communis (Castor bean)". UniProtKB. UniProt Consortium.

- Aplin PJ, Eliseo T (September 1997). "Ingestion of castor oil plant seeds". Med. J. Aust. 167 (5): 260–261. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb125050.x. PMID 9315014. S2CID 42009654.

- Olsnes S, Pihl A (July 1973). "Different biological properties of the two constituent polypeptide chains of ricin, a toxic protein inhibiting protein synthesis". Biochemistry. 12 (16): 3121–3126. doi:10.1021/bi00740a028. PMID 4730499.

- Weston SA, Tucker AD, Thatcher DR, Derbyshire DJ, Pauptit RA (December 1994). "X-ray structure of recombinant ricin A-chain at 1.8 A resolution". J. Mol. Biol. 244 (4): 410–422. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1739. PMID 7990130.

- Wales R, Richardson PT, Roberts LM, Woodland HR, Lord JM (October 1991). "Mutational analysis of the galactose binding ability of recombinant ricin B chain". J. Biol. Chem. 266 (29): 19172–19179. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54978-4. PMID 1717462.

- Harkup K (2015). A is For Arsenic: The poisons of Agatha Christie. London: Bloomsbury Sigma. pp. 222–236. ISBN 978-1-4729-1130-8.

- Magnusson S, Kjeken R, Berg T (March 1993). "Characterization of two distinct pathways of endocytosis of ricin by rat liver endothelial cells". Exp. Cell Res. 205 (1): 118–125. doi:10.1006/excr.1993.1065. PMID 8453986.

- Sphyris N, Lord JM, Wales R, Roberts LM (September 1995). "Mutational analysis of the Ricinus lectin B-chains. Galactose-binding ability of the 2 gamma subdomain of Ricinus communis agglutinin B-chain". J. Biol. Chem. 270 (35): 20292–20297. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.35.20292. PMID 7657599.

- Moya M, Dautry-Varsat A, Goud B, Louvard D, Boquet P (August 1985). "Inhibition of coated pit formation in Hep2 cells blocks the cytotoxicity of diphtheria toxin but not that of ricin toxin". J. Cell Biol. 101 (2): 548–559. doi:10.1083/jcb.101.2.548. PMC 2113662. PMID 2862151.

- Nichols BJ, Lippincott-Schwartz J (October 2001). "Endocytosis without clathrin coats". Trends Cell Biol. 11 (10): 406–412. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02107-9. PMID 11567873.

- Lord MJ, Jolliffe NA, Marsden CJ, Pateman CS, Smith DC, Spooner RA, Watson PD, Roberts LM (2003). "Ricin. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity". Toxicol Rev. 22 (1): 53–64. doi:10.2165/00139709-200322010-00006. PMID 14579547.

- Spooner RA, Smith DC, Easton AJ, Roberts LM, Lord JM (2006). "Retrograde transport pathways utilised by viruses and protein toxins". Virol. J. 3: 26. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-3-26. PMC 1524934. PMID 16603059.

- Spooner RA, Watson PD, Marsden CJ, Smith DC, Moore KA, Cook JP, Lord JM, Roberts LM (October 2004). "Protein disulphide-isomerase reduces ricin to its A and B chains in the endoplasmic reticulum". Biochem. J. 383 (Pt 2): 285–293. doi:10.1042/BJ20040742. PMC 1134069. PMID 15225124.

- Bellisola G, Fracasso G, Ippoliti R, Menestrina G, Rosén A, Soldà S, Udali S, Tomazzolli R, Tridente G, Colombatti M (May 2004). "Reductive activation of ricin and ricin A-chain immunotoxins by protein disulfide isomerase and thioredoxin reductase". Biochem. Pharmacol. 67 (9): 1721–1731. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.013. PMID 15081871.

- Mayerhofer PU, Cook JP, Wahlman J, Pinheiro TT, Moore KA, Lord JM, Johnson AE, Roberts LM (April 2009). "Ricin A chain insertion into endoplasmic reticulum membranes is triggered by a temperature increase to 37 {degrees}C". J. Biol. Chem. 284 (15): 10232–10242. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808387200. PMC 2665077. PMID 19211561.

- Spooner RA, Hart PJ, Cook JP, Pietroni P, Rogon C, Höhfeld J, Roberts LM, Lord JM (November 2008). "Cytosolic chaperones influence the fate of a toxin dislocated from the endoplasmic reticulum". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (45): 17408–17413. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517408S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809013105. JSTOR 25465291. PMC 2580750. PMID 18988734.

- Slominska-Wojewodzka M, Gregers TF, Wälchli S, Sandvig K (April 2006). "EDEM is involved in retrotranslocation of ricin from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol". Mol. Biol. Cell. 17 (4): 1664–1675. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0961. PMC 1415288. PMID 16452630.

- Gregers TF, Skånland SS, Wälchli S, Bakke O, Sandvig K (May 2013). "BiP negatively affects ricin transport". Toxins (Basel). 5 (5): 969–982. doi:10.3390/toxins5050969. PMC 3709273. PMID 23666197.

- Li S, Spooner RA, Allen SC, Guise CP, Ladds G, Schnöder T, Schmitt MJ, Lord JM, Roberts LM (August 2010). "Folding-competent and folding-defective forms of ricin A chain have different fates after retrotranslocation from the endoplasmic reticulum". Mol. Biol. Cell. 21 (15): 2543–2554. doi:10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0743. PMC 2912342. PMID 20519439.

- Deeks ED, Cook JP, Day PJ, Smith DC, Roberts LM, Lord JM (March 2002). "The low lysine content of ricin A chain reduces the risk of proteolytic degradation after translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol". Biochemistry. 41 (10): 3405–3413. doi:10.1021/bi011580v. PMID 11876649.

- Pietroni P, Vasisht N, Cook JP, Roberts DM, Lord JM, Hartmann-Petersen R, Roberts LM, Spooner RA (April 2013). "The proteasome cap RPT5/Rpt5p subunit prevents aggregation of unfolded ricin A chain". Biochem. J. 453 (3): 435–445. doi:10.1042/BJ20130133. PMC 3778710. PMID 23617410.

- Endo Y, Tsurugi K (June 1987). "RNA N-glycosidase activity of ricin A-chain. Mechanism of action of the toxic lectin ricin on eukaryotic ribosomes" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 262 (17): 8128–8130. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47538-2. PMID 3036799.

- Endo Y, Tsurugi K (June 1988). "The RNA N-glycosidase activity of ricin A-chain. The characteristics of the enzymatic activity of ricin A-chain with ribosomes and with rRNA" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 263 (18): 8735–8739. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68367-X. PMID 3288622.

- Sperti S, Montanaro L, Mattioli A, Stirpe F (November 1973). "Inhibition by ricin of protein synthesis in vitro: 60 S ribosomal subunit as the target of the toxin". Biochem. J. 136 (3): 813–815. doi:10.1042/bj1360813. PMC 1166019. PMID 4360718.

- Ujváry I (2010). Krieger R (ed.). Hayes´ Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology (Third ed.). Elsevier, Amsterdam. pp. 119–229. ISBN 978-0-12-374367-1.

- "CDC – The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database: Biotoxin: RICIN – NIOSH". cdc.gov. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Schep LJ, Temple WA, Butt GA, Beasley MD (November 2009). "Ricin as a weapon of mass terror – separating fact from fiction". Environ Int. 35 (8): 1267–1271. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2009.08.004. PMID 19767104.

- Kopferschmitt J, Flesch F, Lugnier A, Sauder P, Jaeger A, Mantz JM (April 1983). "Acute voluntary intoxication by ricin". Hum Toxicol. 2 (2): 239–242. doi:10.1177/096032718300200211. PMID 6862467. S2CID 21965711.

- Rincon P (11 November 2009). "Ricin 'antidote' to be produced". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- "Human trial proves ricin vaccine safe, induces neutralizing antibodies; further tests planned". University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Fleming-Michael K (1 September 2005). "Vaccine for ricin toxin developed at Detrick lab". Dcmilitary.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Levy J (2011). Poison: An Illustrated History. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-7627-7056-4.

- "Oil cake (chemistry)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Soto-Blanco B, Sinhorini IL, Gorniak SL, Schumaher-Henrique B (June 2002). "Ricinus communis cake poisoning in a dog". Vet Hum Toxicol. 44 (3): 155–156. PMID 12046967.

- Wedin GP, Neal JS, Everson GW, Krenzelok EP (May 1986). "Castor bean poisoning". Am J Emerg Med. 4 (3): 259–261. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(86)90080-X. PMID 3964368.

- Rauber A, Heard J (December 1985). "Castor bean toxicity re-examined: a new perspective". Vet Hum Toxicol. 27 (6): 498–502. PMID 4082461.

- "Survived after ingesting 30 castor beans". The Salt Lake Tribune. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- Baselt RC (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (Ninth ed.). Seal Beach, California: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1497–1499. ISBN 978-0-9626523-8-7.

- "HHS and USDA Select Agents and Toxins 7 CFR Part 331, 9 CFR Part 121, and 42 CFR Part 73" (PDF). cdc.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2009.

- "Permissible Toxin Amounts". National Select Agent Registry. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355 – The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations (1 July 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Augerson WS, Spektor DM (2000). A Review of the Scientific Literature as it Pertains to Gulf War Illnesses. Rand Corporation (Report). Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents. Vol. 5. United States Dept. of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, National Defense Research Institute (U.S.). doi:10.7249/MR1018.5. ISBN 978-0-8330-2680-4.

- "The Avalon Project – Laws of War: Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague II); July 29, 1899". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Gupta R (2009). Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374484-5.

- Romano Jr JA, Salem M, Lukey BJ (2007). Chemical Warfare Agents: Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutics, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-1-4200-4662-5.

- "Ricin – Biological Weapons". www.globalsecurity.org.

- "Poison-tip umbrella assassination of Georgi Markov reinvestigated". 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- "Cornell University Department of Animal Science". Ansci.cornell.edu. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Kortepeter MG, Parker GW (1999). "Potential biological weapons threats". Emerging Infect. Dis. 5 (4): 523–527. doi:10.3201/eid0504.990411. PMC 2627749. PMID 10458957.

- van Aken J (2001). "Biological Weapons: Research Projects of the German Army". Backgrounder Series No. 7. The Sunshine Project. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013.

- "RiVax™ Ricin Toxin Vaccine". Soligenix, Inc. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Hackett DW (11 February 2019). "Ricin Vaccine Candidate Rivax Awarded Patent Protection". Precision Vaccinations. Houston TX: Precision Vax Llc. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Stillmark, Hermann (1888). Über Ricin, ein giftiges Ferment aus den Samen von Ricinus comm. L. und einigen anderen Euphorbiaceen [About ricin, a poisonous ferment [i.e., enzyme] from the seeds of Ricinus communis L. and some other Euphorbiaceae] (M.D. thesis) (in German). Dorpat, Estonia: University of Dorpat.

- Stillmark H (1889). "Ueber ricin" [About ricin]. Arbeiten des Pharmakologischen Institutes zu Dorpat (in German). 3: 59–151.

- The Russian physician N.A. Bubnow and the Australian physician Thomas Storie Dixson (1854–1932) probably isolated ricin in 1887 at the University of Strassburg (Strasbourg), Germany; however, Dixson mistakenly believed that ricin was a glycoside, whereas it is actually a protein.

- Dixson, Thomas (March 1887). "Ricinus communis". Australasian Medical Gazette. 6: 137–138, 155–158.

- Vogl A (1892). Pharmakognosie (in German). Vienna, Austria: Carl Gerold's Sohn. p. 204. From p. 204: "Bubnow und Dixson (1887) erhielten aus den entfetteten Samen … vielleicht eine sogenannte Phytalalbumose darstellt." (Bubnow and Dixson (1887) obtained, from the defatted seeds by extraction with dilute hydrochloric acid, a glycoside ([which they called] Ricinon) that belongs to the acid anhydrides [and that is] of very drastic effect. Mr. Stillmark (1889) finally precipitated, from the seeds and oilcake, a very poisonous substance, Ricin, (about 3% of the air-dried seeds) that's insoluble in alcohol and that probably is a protein, an amorphous enzyme, perhaps a so-called phytalbumin.)

- Finnemore H (29 July 1905). "Castor oil – part 1". Pharmaceutical Journal. 75: 137–138. See p. 137.

- Cook B. Dixson, Thomas Storie (1854–1932). Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- "Ricin and the umbrella murder". CNN. 7 January 2003. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Thomas DM (1998). Alexander Solzhenitsyn: A Century in His Life (First ed.). St. Martin's Press. pp. 368–378. ISBN 978-0756760113.

- "Letters to NYC Mayor Bloomberg contained ricin". MSN News. Associated Press. 30 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013.

- Harris P (8 June 2013). "Bit-part actor charged over plot to frame husband for ricin letters". The Guardian.

- McLaughlin EC (16 July 2014). "Texas actress who sent Obama ricin sentenced to 18 years". CNN. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Ricin detected in mail sent to Pentagon". CNN. 10 October 2018.

- Maravelias P (27 July 2019). "Suspicious substance which caused Pelican Bay building evacuation identified as ricin". KRCR-TV.

- Roth A (27 April 2020). "Prague mayor under police protection amid reports of Russian plot". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Police protecting Prague mayor after 'murder plot'". BBC News. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Mortkowitz S (6 May 2020). "Czech president lashes out at Prague mayor under police protection". Politico. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Things You Should Know About Ricin Before Watching the 'Breaking Bad' Finale". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. 27 September 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Woman tried to poison mother in plot inspired by Breaking Bad, court told". The Guardian. London. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Noble A (15 September 2014). "Guilty plea in Georgetown University ricin case with tie to 'Breaking Bad'". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Breaking Bad fan guilty of Dark Web ricin plot". BBC News. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

External links

- Studies showing lack of toxicity of castor oil from the US Public Health Service

- Castor bean information at Purdue University

- Plants Poisonous to Livestock – Ricin information at Cornell University

- Ricin cancer therapy tested at BBC

- Ricin – Emergency Preparations at CDC

- Emergency Response Card – Ricin at CDC

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02879 (Ricin) at the PDBe-KB.