Carfentanil

Carfentanil or carfentanyl, sold under the brand name Wildnil, is a potent opioid analgesic which is used in veterinary medicine to anesthetize large animals such as elephants and bears.[1] It is typically administered in this context by tranquilizer dart.[1] Carfentanil has also been used in humans for imaging of opioid receptors.[1] It has additionally been used as a recreational drug, typically by injection, insufflation, or inhalation.[1] Deaths have been reported in association with carfentanil.[1][2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Wildnil |

| Other names | (4-Methoxycarbonyl)fentanyl |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 7.7 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

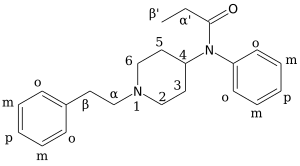

| Formula | C24H30N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 394.515 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Effects and side effects of carfentanil in humans are similar to those of other opioids and include euphoria, relaxation, pain relief, pupil constriction, drowsiness, sedation, slowed heart rate, low blood pressure, lowered body temperature, loss of consciousness, and suppression of breathing.[1] The effects of carfentanil, including overdose, can be reversed by the opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone, though higher or multiple doses than usual may be necessary compared to other opioids.[1][2][3]: 23 Carfentanil is a structural analogue of the synthetic opioid analgesic fentanyl.[4] It acts as an ultrapotent and highly selective agonist of the μ-opioid receptor.[1]

Carfentanil was first synthesized in 1974 by a team of chemists at Janssen Pharmaceutica which included Paul Janssen.[5] It was introduced into veterinary medicine in 1986.[1] Carfentanil is legally controlled in most jurisdictions.[2]

Uses

Veterinary use

Chosen for its high therapeutic index, carfentanil was first sold in 1986 under the brand name "Wildnil" for use in combination with an α2-receptor agonist as a tranquilizing agent[3]: 9 for large mammals like hippos, rhinos, and elephants.[5][6] Commercial production of Wildnil ceased in 2003; the drug is now available only in compounded form.[7]

Clinical use

Carfentanil has been used at doses of less than 7 μg as a radiotracer for positron emission tomography imaging of the μ-opioid receptor in the brain in humans.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Carfentanil acts as a highly selective agonist of the μ-opioid receptor.[8] It showed affinity values (Ki) of 0.051 nM for the μ-opioid receptor, 4.7 nM for the δ-opioid receptor, and 13 nM for the κ-opioid receptor in rat brain.[8] Thus, carfentanil displayed 90- and 250-fold selectivity for the μ-opioid receptor over the δ-opioid receptor and the κ-opioid receptor, respectively.[8] With human proteins, the affinities were 0.024 nM for the μ-opioid receptor, 3.3 nM for the δ-opioid receptor, and 43 nM for the κ-opioid receptor, demonstrating 140- and 1,800-fold selectivity for the μ-opioid receptor over the δ- and κ-opioid receptors, respectively.[9] Carfentanil appears to have higher affinity for the μ1-opioid receptor over the μ2-opioid receptor.[1] Carfentanil has approximately 10,000 times the analgesic potency of morphine, 4,000 times the potency of heroin, and 20 to 100 times the potency of fentanyl in animal studies.[9][1][2] The effects of carfentanil are reversed by μ-opioid receptor antagonists like naloxone and naltrexone, though higher than normal doses of these agents may be necessary in humans due to the extremely high potency of carfentanil.[1][2]

Pharmacokinetics

A lipophilic chemical that can easily cross the blood–brain barrier, carfentanil has a very rapid onset of action and is longer acting than fentanyl.[3]: 9 Its elimination half-life in humans was 42 to 51 minutes following an intravenous bolus at an average dose of 1.34 μg (19 ng/kg).[1][2] However, in a case study of recreational exposure, the half-lives of carfentanil and its metabolite norcarfentanil were estimated to be 5.7 hours and 11.8 hours, respectively.[1][10]

Chemistry

Carfentanil is an analogue of fentanyl and is also known as (4-methoxycarbonyl)fentanyl. Related analogues of fentanyl include 4-phenylfentanyl, lofentanil (3-methylcarfentanyl), N-methylcarfentanil, R-30490 (4-methoxymethylfentanyl), sufentanil, and thiafentanil.

History

Increase in illicit use

Over three hundred cases of overdose related to fentanyl and fentanyl analogues were reported between August and November 2016 in several of the United States, including Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, Kentucky and Florida.[14] In 2017, a Milwaukee, Wisconsin, man died from a carfentanil overdose, likely taken unknowingly with another illegal drug such as heroin or cocaine.[15] Carfentanil is most often taken with heroin or by users who believe they are taking heroin. Carfentanil is added to or sold as heroin because it is less expensive, easier to obtain, and easier to manufacture than heroin.[16] Health professionals are concerned about the potential escalation of public health consequences of its recreational use.[17]

Importation from China

Authorities in Latvia and Lithuania reported seizing carfentanil as an illicit drug in the early 2000s.[16][18]

Around 2016, the United States and Canada reported a dramatic increase in shipment of carfentanil and other strong opioid drugs to customers in North America from Chinese chemical supply firms. In June 2016 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police seized one kilogram of carfentanil shipped from China in a box labeled "printer accessories". According to the Canada Border Services Agency, the shipment contained 50 million lethal doses of the drug, more than enough to annihilate the entire population of the country, in containers labeled as toner cartridges for HP LaserJet printers.[16]

Carfentanil was not a controlled substance in China until 1 March 2017,[19] and until then was manufactured legally and sold openly over the Internet, being actively marketed by several Chinese chemical companies.[16]

Moscow theater hostage crisis

In 2012, a team of researchers at the British chemical and biological defence laboratories at Porton Down found carfentanil and remifentanil in clothing from two British survivors of the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis and in the urine from a third survivor. The team concluded that the Russian military had used an aerosol mist of carfentanil and remifentanil to subdue Chechen hostage takers.[20] Researchers had previously surmised from the available evidence that the Moscow emergency services had not been informed of the use of the agent, despite being instructed to bring opioid antagonists to the scene. Unaware that hundreds of patients had been exposed to high doses of strong opioids, the emergency workers failed to bring sufficient quantities of naloxone and naltrexone to counteract the effects of carfentanil and remifentanil. As a result, one hundred twenty-five people exposed to the aerosol are confirmed to have died from respiratory failure during the incident.[21]

Potential as a chemical weapon

The toxicity of carfentanil in humans and its ready commercial availability has raised concerns over its potential use as a chemical weapon of mass destruction by rogue nations and terrorist groups. The toxicity of carfentanil has been compared to that of nerve gas.[16]

Society and culture

China

Carfentanil has been controlled in China since 1 March 2017.[3]: 21 The trade war between China and the US has included controversy over the effectiveness of this control.[22][23][24]

United States

Carfentanil is classified as Schedule II under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States with a DEA ACSCN of 9743 and a 2016 annual aggregate manufacturing quota of 19 grams (less than 0.7 oz.).[25]

United Kingdom

Carfentanil has been specifically controlled as a Class A drug since 1986.[26]

See also

References

- Zawilska JB, Kuczyńska K, Kosmal W, Markiewicz K, Adamowicz P (March 2021). "Carfentanil - from an animal anesthetic to a deadly illicit drug". Forensic Sci Int. 320: 110715. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2021.110715. PMID 33581655. S2CID 231918983.

- Misailidi N, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, Dona A, Spiliopoulou C, Athanaselis S (2018). "Fentanyls continue to replace heroin in the drug arena: the cases of ocfentanil and carfentanil". Forensic Toxicol. 36 (1): 12–32. doi:10.1007/s11419-017-0379-4. PMC 5754389. PMID 29367860.

- "Report on the risk assessment of methyl 1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-[phenyl(propanoyl) amino]piperidine-4-carboxylate in the framework of the Council Decision on new psychoactive substances" (PDF). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 8 July 2018.

- "Fentanyl drug profile". EMCDDA.

- Stanley TH, Egan TD, Van Aken H (February 2008). "A tribute to Dr. Paul A. J. Janssen: entrepreneur extraordinaire, innovative scientist, and significant contributor to anesthesiology". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 106 (2): 451–62, table of contents. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181605add. PMID 18227300. S2CID 20490363.

- Jacobson ER, Kollias GV, Heard DJ, Caligiuri R (1988). "Immobilization of African Elephants with Carfentanil and Antagonism with Nalmefene and Diprenorphine". The Journal of Zoo Animal Medicine. 19 (1/2): 1–7. doi:10.2307/20094842. JSTOR 20094842.

- World Health Organisation, Carfentanil Critical Review Report (PDF), retrieved 3 September 2018

- Frost JJ, Wagner HN, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Links JM, Wilson AA, Burns HD, Wong DF, McPherson RW, Rosenbaum AE (1985). "Imaging opiate receptors in the human brain by positron tomography". J Comput Assist Tomogr. 9 (2): 231–6. doi:10.1097/00004728-198503000-00001. PMID 2982931. S2CID 30414509.

- Leen JL, Juurlink DN (April 2019). "Carfentanil: a narrative review of its pharmacology and public health concerns". Can J Anaesth. 66 (4): 414–421. doi:10.1007/s12630-019-01294-y. PMID 30666589. S2CID 58642995.

- Uddayasankar, Uvaraj; Lee, Colin; Oleschuk, Curtis; Eschun, Gregg; Ariano, Robert E. (June 2018). "The Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Carfentanil After Recreational Exposure: A Case Report". Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 38 (6): e41–e45. doi:10.1002/phar.2117.

- "Fentanyl. Image 4 of 17". Drug Enforcement Administration.

- "DEA Issues Carfentanil Warning To Police And Public". United States Drug Enforcement Administration. 22 September 2016.

The lethal dose range for carfentanil in humans is unknown

- Concheiro M, Chesser R, Pardi J, Cooper G (2018). "Postmortem Toxicology of New Synthetic Opioids". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9: 1210. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01210. PMC 6212520. PMID 30416445. 26 October 2018. From the conclusion: "Postmortem concentrations seemed to correlate with their potency, although the presence of other CNS depressants, such as ethanol and benzodiazepines has to be taken into account."

- Sanburn J. "Heroin Is Being Laced With a Terrifying New Substance". Time. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Stephenson C (17 April 2017). "Carfentanil, 10,000 times more potent than morphine, kills homeless man in Milwaukee". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Kinetz E, Butler D (7 October 2016). "Chemical weapon for sale: China's unregulated narcotic". AP News. New York, NY 10281 USA. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Baumann MH, Pasternak GW (January 2018). "Novel Synthetic Opioids and Overdose Deaths: Tip of the Iceberg?". Neuropsychopharmacology. 43 (1): 216–217. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.211. PMC 5719114. PMID 29192657.

- Mounteney J, Giraudon I, Denissov G, Griffiths P (July 2015). "Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 26 (7): 626–31. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.003. PMID 25976511.

- "China makes deadly opioid carfentanil a controlled substance". Associated Press via theday.com. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Riches JR, Read RW, Black RM, Cooper NJ, Timperley CM (November 2012). "Analysis of clothing and urine from Moscow theatre siege casualties reveals carfentanil and remifentanil use". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 36 (9): 647–56. doi:10.1093/jat/bks078. PMID 23002178.

- Wax PM, Becker CE, Curry SC (May 2003). "Unexpected "gas" casualties in Moscow: a medical toxicology perspective". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 41 (5): 700–5. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.148. PMID 12712038. S2CID 44761840.

- Bernstein, Leandra (3 October 2018). "Drug trade war: Chinese fentanyl is fueling the US opioid crisis". WJLA. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Landay, Jonathan (2 August 2019). "Trump accuses China's Xi of failing to halt fentanyl exports to U.S." Reuters. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Myers, Steven Lee (1 December 2019). "China Cracks Down on Fentanyl. But Is It Enough to End the U.S. Epidemic?". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "Established Aggregate Production Quotas for Schedule I and II Controlled Substances and Assessment of Annual Needs for the List I Chemicals Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine for 2016". Federal Register. 6 October 2015.

- "Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (c. 38): SCHEDULE 2: Controlled Drugs". Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 15 June 2009.