Carisoprodol

Carisoprodol, sold under the brand name Soma among others, is a medication used for musculoskeletal pain.[3] Use is only approved for up to three weeks.[3] Effects generally begin within half an hour and last for up to six hours.[3] It is taken orally.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /kərˌaɪsʌˈproʊdɒl/ kər-EYE-suh-PROH-dol |

| Trade names | Soma, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682578 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Carbamate |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 60% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Metabolites | Meprobamate |

| Onset of action | Rapid (30 minutes[2]) |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5 hours [12 hours[nb 1]] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

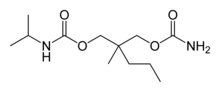

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.017 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H24N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 260.334 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include headache, dizziness, and sleepiness.[3] Serious side effect may include addiction, allergic reactions, and seizures.[3] In people with a sulfa allergy certain formulations may result in problems.[3] Safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding is not clear.[3][4] How it works is not clear.[3] Some of its effects are believed to occur following being converted into meprobamate.[3]

Carisoprodol was approved for medical use in the United States in 1959.[3] Its approval in Europe was withdrawn in 2008.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2017, it was the 255th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[6][7] In the United States, it is a Schedule IV controlled substance.[3]

Medical uses

Carisoprodol is meant to be used along with rest, physical therapy and other measures to relax muscles after strains, sprains and muscle injuries.[8] It comes in tablet format and is taken by the mouth three times a day and before bed.[8]

Side effects

The usual dose of 350 mg is unlikely to engender prominent side effects other than somnolence, and mild to significant euphoria or dysphoria, but the euphoria is generally short-lived due to the fast metabolism of carisoprodol into meprobamate and other metabolites; the euphoria derived is, according to new research, most likely due to carisoprodol's inherent, potent anxiolytic effects that are far stronger than those produced by its primary metabolite, meprobamate, which is often misblamed for the drug-seeking associated with carisoprodol, as carisoprodol itself is responsible for the significantly more intense central nervous system effects than meprobamate alone. Carisoprodol has a qualitatively different set of effects to that of meprobamate (Miltown). The medication is well tolerated and without adverse effects in the majority of patients for whom it is indicated. In some patients, however, and/or early in therapy, carisoprodol can have the full spectrum of sedative side effects and can impair the patient's ability to operate a firearm, motor vehicles, and other machinery of various types, especially when taken with medications containing alcohol, in which case an alternative medication would be considered. The intensity of the side effects of carisoprodol tends to lessen as therapy continues, as is the case with many other drugs. Other side effects include: dizziness, clumsiness, headache, fast heart rate, upset stomach, vomiting and skin rash.[8]

The interaction of carisoprodol with essentially all opioids, and other centrally acting analgesics, but especially codeine, those of the codeine-derived subgroup of the semisynthetic class (ethylmorphine, dihydrocodeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, nicocodeine, benzylmorphine, the various acetylated codeine derivatives including acetyldihydrocodeine, dihydroisocodeine, nicodicodeine and others) which allows the use of a smaller dose of the opioid to have a given effect, is useful in general and especially where skeletal muscle injury and/or spasm is a large part of the problem. The potentiation effect is also useful in other pain situations and is also especially useful with opioids of the open-chain class, such as methadone, levomethadone, ketobemidone, phenadoxone and others. In recreational drug users, deaths have resulted from combining doses of hydrocodone and carisoprodol. Another danger of misuse of carisoprodol and opiates is the potential to aspirate while unconscious.

Meprobamate and other muscle-relaxing drugs often were subjects of misuse in the 1950s and 60s.[9][10] Overdose cases were reported as early as 1957, and have been reported on several occasions since then.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

Carisoprodol is metabolized by the liver and excreted by the kidneys so this drug must be used with caution with patients that have impaired hepatic or renal function.[18] Because of potential for more severe side effects, this drug is on the list to avoid for elderly people.[19]

Withdrawal

Carisoprodol, meprobamate, and related drugs such as tybamate, have the potential to produce physical dependence of the barbiturate type following periods of prolonged use. Withdrawal of the drug after extensive use may require hospitalization in medically compromised patients. In severe cases the withdrawal can mimic the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal including the potentially lethal status epilepticus.

Psychological dependence has also been linked to carisoprodol use[20] although this is much less severe than with meprobamate itself (presumably due to the slower onset of effects). Psychological dependence is more common in those who use carisoprodol non-medically and those who have a history of substance use (particularly sedatives or alcohol). It may reach clinical significance before physiological tolerance and dependence have occurred and (as with benzodiazepines) has been demonstrated to persist to varying degrees of severity for months or years after discontinuation.

Discontinuation of carisoprodol, as with all GABA-ergics, can result in cognitive changes which persist for weeks, months, or rarely even years including greatly increased anxiety and depression, social withdrawal, hair-trigger agitation/aggression, chronic insomnia, new or aggravated (often illogical) phobias, reduced IQ, short term and long-term memory loss, and dozens of other sequelae.[21] The effects, severity, and duration appear to be slightly dose-dependent but are mainly determined by the patients pattern of use (taken as prescribed, taken in bulk doses, mixed with other drugs, a combination of the above, etc.), genetic predisposition to substance use, and a history of substance use all increase the patients risk of persistent discontinuation syndrome symptoms.

Treatment for physical withdrawal generally involves switching the patient to a long-acting benzodiazepine such as diazepam or clonazepam then slowly titrating them off the replacement drug completely at a rate which is both reasonably comfortable for the patient but rapid enough for the managing physician to consider the rate of progress acceptable (overly rapid dose reduction greatly increases the risk of patient non-compliance such as the use of illicitly obtained alternative sedatives and/or alcohol). Psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have demonstrated moderate success in reducing the rebound anxiety which results upon carisoprodol discontinuation but only when combined with regular and active attendance to a substance use support group.

Carisoprodol withdrawal can be life-threatening (especially in high dose users and those who attempt to quit "cold turkey"). Medical supervision is recommended, with gradual reduction of dose of carisoprodol or a substituted medication, typical of other depressant drugs.

Non-medical use

Combining a muscle relaxant like carisoprodol with opioids and benzodiazepines is referred to as "The Holy Trinity" as it has been reported to increase the power of the "high".[22]

Recreational users of carisoprodol usually seek its potentially heavy sedating, relaxant, and anxiolytic effects.[23] Also, because of its potentiating effects on narcotics, it is often used in conjunction with many opioid drugs. Also it is not detected on standard drug testing screens. On 26 March 2010 the DEA issued a Notice of Hearing on proposed rule making in respect to the placement of carisoprodol in schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act.[24] The DEA ended up classifying it under schedule IV.[25] Carisoprodol is sometimes mixed with date rape drugs.[26]

Many overdoses have resulted from recreational users combining these drugs to combine their individual effects without being aware of the enzyme-induction induced potentiation.

Overdose

As with other GABAergic drugs, combination with other GABAergic drugs, including alcohol, as well as with sedatives in general, possess a significant risk to the user in the form of overdose. Overdose symptoms are similar to those of other GABAergics including excessive sedation and unresponsiveness to stimuli, severe ataxia, amnesia, confusion, agitation, intoxication and inappropriate (potentially violent) behavior. Severe overdoses may present with respiratory depression (and subsequent pulmonary aspiration), coma, and death.

Carisoprodol is not detected on all toxicology tests which may delay diagnosis of overdose. Overdose symptoms in combination with opiates are similar but are distinguished by the presentation of normal or pinpoint pupils, which are generally unresponsive to light. Carisoprodol (as with its metabolite meprobamate) is particularly dangerous in combination with alcohol. Flumazenil (the benzodiazepine antidote) is not effective in the management of carisoprodol overdose as carisoprodol acts at the barbiturate binding site. Treatment mirrors that of barbiturate overdoses and is generally supportive, including the administration of mechanical respiration and pressors as implicated (and in rare cases, bemegride). Total amnesia of the experience is not uncommon following recovery.

In 2014 actress Skye McCole Bartusiak died of an overdose due to the combined effects of carisoprodol, hydrocodone and difluoroethane.[27]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Carisoprodol, has a chemical structure similar to Glutamate, a neurotransmitter, and dimethylglycine. Upon analysis, this pharmacological agent seems to be an agonist of the NMDA receptor, with an unknown [Km]. Because excess Glutamate causes excitotoxicity and neuronal apoptosis, Carisoprodol overdose may also lead to NMDA related toxicity, thus inducing seizures at high doses, and muscle relaxation upon administration.

Carisoprodol's structural similarity to Meprobamate indicates GABAergic activity, including GABA A agonism, similar to the mechanism of benzodiazepines.[28] This will allow for further muscle relaxation and anxiety reduction. Therefore, Carisoprodol, at low to moderate dosages, may be clinically indicated for absent seizures, yet exacerbate Tonic-clonic seizures.

Pharmacokinetics

Carisoprodol has a rapid, 30-minute onset of action, with the aforementioned effects lasting about two to six hours. It is metabolized in the liver via the cytochrome P450 oxidase isozyme CYP2C19, excreted by the kidneys and has about an eight-hour half-life. In patients with low levels of CYP2C19 (poor metabolizers), standard doses can lead to increased concentrations of carisoprodol (up-to a four-fold increase).[29] A considerable proportion of carisoprodol is metabolized to meprobamate, which is a known addictive substance; this could account for the addictive potential of carisoprodol (meprobamate levels reach higher peak plasma levels than carisoprodol itself following administration). As mentioned above, carisoprodol appears to have strong anxiolytic effects on its own; however, a large part of its effects also come from the fact that it is metabolized into meprobamate: at least a 25% of the carisoprodol administered will be transformed into meprobamate which means that meprobamate is 3.25× stronger than carisoprodol (although this rate varies from person to person according to their levels of CYP2C19 enzymes in their livers with some people having considerably higher levels) or, in other words, 200 mg of meprobamate (which is the lowest standard dose) is equivalent to 650 mg of carisoprodol.[2] As such, meprobamate is believed to play a significant role in the effects of carisoprodol and meprobamate's long half-life results in bioaccumulation following extended periods of carisoprodol administration.

It is slightly soluble in water and freely soluble in ethanol, chloroform and acetone. The drug's solubility is practically independent of pH.

History

On 1 June 1959, several American pharmacologists convened at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan to discuss a newly discovered structural analogue of meprobamate. The substitution of one hydrogen atom with an isopropyl group on one of the carbamyl nitrogens was intended to yield a drug with new pharmacological properties. It had been developed by Frank Berger at Wallace Laboratories and was named carisoprodol.[30]

Building on meprobamate's pharmacological effects, carisoprodol was intended to have better muscle relaxing properties, less potential for addiction, and a lower risk of overdose. Carisoprodol's effect profile did indeed turn out to differ significantly with respect to meprobamate, with carisoprodol possessing stronger muscle relaxant and analgesic effects.[31]

Usage and legal status

Norway

Reports from Norway have shown carisoprodol has addictive potential[32] as a prodrug of meprobamate and/or potentiator of hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, and similar drugs. In May 2008 it was taken off the market in Norway.[33]

European Union

In the EU, the European Medicines Agency issued a release recommending member states suspend marketing authorization for this product in the treatment of acute (not chronic) back pain.[34]

As of November 2007, carisoprodol has been taken off the market in Sweden due to problems with dependence and side effects. The agency overseeing pharmaceuticals considered other drugs used with the same indications as carisoprodol to have the same or better effects without the risks of the drug.[35]

United States

Until 12 December 2011, when the administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued the final ruling placing the substance carisoprodol into Schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), carisoprodol was not a controlled substance. The placement of carisoprodol into Schedule IV was effective 11 January 2012.[36]

Carisoprodol is available generically as 350 mg and, more recently, 250 mg tablets. Compounded tablets with acetaminophen and codeine are also available.[37]

Canada

Federally, carisoprodol is a prescription drug (Schedule I, sub-schedule F1).[38] Provincial regulations vary.[39] It is no longer readily available.

Indonesia

- In September 2013, carisoprodol was taken off the market due to problems with diversion, dependence and side effects.

- In September 2017, one child died and 50 had seizures when PCC, which stands for "Paracetamol Caffeine Carisoprodol" was mixed (probably illicit) into children's drinks in elementary and junior high schools in Kendari.[40]

Notes

- At least 25% of the carisoprodol in the body is transformed by the liver into meprobamate, its main active metabolite, which in turn has a half-life of 10 hours.[2]

References

- "Carisoprodol". drugs.com. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Carrasco A (13 September 2019). "Letra C (Carisoprodol)". In Carrasco Ruiz MA, Chavez Pulido X, Morales E (eds.). Diccionario de Especialidades Farmaceúticas PLM. Diccion (in Spanish). Vol. I (65th ed.). Mexico City: PLM Latinoamérica. p. 222. ISBN 978-607-625-072-3. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- "Carisoprodol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "DailyMed - carisoprodol tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Carisoprodol". European Medicines Agency. 15 November 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Carisoprodol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Carisoprodol". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Kamin I, Shaskan DA (June 1959). "Death due to massive overdose of meprobamate". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 115 (12): 1123–4. doi:10.1176/ajp.115.12.1123-a. PMID 13649976.

- Hollister LE (1983). "The pre-benzodiazepine era". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 15 (1–2): 9–13. doi:10.1080/02791072.1983.10472117. PMID 6350551.

- Gaillard Y, Billault F, Pépin G (May 1997). "Meprobamate overdosage: a continuing problem. Sensitive GC-MS quantitation after solid phase extraction in 19 fatal cases". Forensic Science International. 86 (3): 173–80. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(97)02128-2. PMID 9180026.

- Allen MD, Greenblatt DJ, Noel BJ (December 1977). "Meprobamate overdosage: a continuing problem". Clinical Toxicology. 11 (5): 501–15. doi:10.3109/15563657708988216. PMID 608316.

- Kintz P, Tracqui A, Mangin P, Lugnier AA (June 1988). "Fatal meprobamate self-poisoning". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 9 (2): 139–40. doi:10.1097/00000433-198806000-00009. PMID 3381792.

- Eeckhout E, Huyghens L, Loef B, Maes V, Sennesael J (1988). "Meprobamate poisoning, hypotension and the Swan-Ganz catheter". Intensive Care Medicine. 14 (4): 437–8. doi:10.1007/BF00262904. PMID 3403779. S2CID 2784867.

- Lhoste F, Lemaire F, Rapin M (April 1977). "Treatment of hypotension in meprobamate poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 296 (17): 1004. doi:10.1056/NEJM197704282961717. PMID 846530.

- Bedson HS (February 1959). "Coma due to meprobamate intoxication; report of a case confirmed by chemical analysis". Lancet. 1 (7067): 288–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90209-0. PMID 13632000.

- Blumberg AG, Rosett HL, Dobrow A (September 1959). "Severe hypotensive reactions following meprobamate overdosage". Annals of Internal Medicine. 51 (3): 607–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-51-3-607. PMID 13801701.

- "CARISOPRODOL". TOXNET. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- NCQA's HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly Archived 1 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "What is Carisoprodol used for?". Pain o Soma medicines. 19 March 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, Crowe SF (April 2004). "Persistence of cognitive effects after withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine use: a meta-analysis". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 19 (3): 437–54. doi:10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00096-9. PMID 15033227.

- Horsfall JT, Sprague JE (February 2017). "The Pharmacology and Toxicology of the 'Holy Trinity'". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 120 (2): 115–119. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12655. PMID 27550152. S2CID 25909460.

- "DEA Drugs & Chemicals of Concern "Carisoprodol"". Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Carisoprodol Into Schedule IV; Announcement of Hearing". Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "Carisoprodol" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division, Drug & Chemical Evaluation Section. U.S. Department of Justice. December 2019.

- Madea B, Musshoff F (May 2009). "Knock-out drugs: their prevalence, modes of action, and means of detection". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 106 (20): 341–7. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0341. PMC 2689633. PMID 19547737.

- Duke A (22 July 2014). "'Patriot' actress Skye McCole Bartusiak dead at 21". CNN Entertainment. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Conermann, Till; Christian, Desirae (2022), "Carisoprodol", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31971718, retrieved 23 February 2022

- Dean, Laura (4 April 2017). "Carisoprodol Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". Medical Genetics Summaries. PMID 28520382.

- Miller JG, ed. The pharmacology and clinical usefulness of carisoprodol. Detroit:Wayne State University; 1959.

- Berger FM, Kletzkin M, Ludwig BJ, Margolin S (March 1960). "The history, chemistry, and pharmacology of carisoprodol". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 86 (1): 90–107. Bibcode:1960NYASA..86...90B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb42792.x. PMID 13799302. S2CID 11909344.

- Bramness JG, Furu K, Engeland A, Skurtveit S (August 2007). "Carisoprodol use and abuse in Norway: a pharmacoepidemiological study". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 64 (2): 210–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02847.x. PMC 2000626. PMID 17298482.

- "Somadril trekkes fra markedet" [Somadril is withdrawn from the market]. Norwegian Medicines Agency (in Norwegian). 20 April 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Carisprodol press release" (PDF). EMEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- "Marknadsföringen av Somadril och Somadril comp rekommenderas upphöra tillfälligt" [Marketing of Somadril and Somadril is recommended to cease temporarily] (in Swedish). 16 November 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- US Department of Justice (2011). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Carisoprodol into Schedule IV" (PDF). Federal Register. 76 (238): 77330–77360. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "High Cost, No Benefit – The Rheumatologist". the-rheumatologist.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "NAPRA – Search National Drug Schedule". National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities. 2009. Archived from the original (ASP) on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- For British Columbia, see library.bcpharmacists.org/D-Legislation_Standards Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "One Schoolchild Dies, More Than 50 Suffer Seizures After Consuming Pills in Southeast Sulawesi". Jakarta Globe. 14 September 2017.

Further reading

- Dean L (2017). "Carisoprodol Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520377. Bookshelf ID: NBK425390.