Bromazepam

Bromazepam, sold under many brand names, is a benzodiazepine. It is mainly an anti-anxiety agent with similar side effects to diazepam (Valium). In addition to being used to treat anxiety or panic states, bromazepam may be used as a premedicant prior to minor surgery. Bromazepam typically comes in doses of 3 mg and 6 mg tablets.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lexotan, Lexotanil, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 84% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 12–20 hours (avg. 17hr)[1] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.748 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H10BrN3O |

| Molar mass | 316.158 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

It was patented in 1961 by Roche and approved for medical use in 1974.[3]

Medical uses

Treatment of severe anxiety.[4] Despite certain side effects and the emergence of alternative products (e.g pregabalin), benzodiazepine medication remains an effective way of reducing problematic symptoms, and is typically deemed effective by patients[5][6] and medical professionals.[7][8][9] Similarly to other intermediate-acting depressants, it may be used as hypnotic medication[10] or in order to mitigate withdrawal effects of alcohol consumption.[11][12][13]

Pharmacology

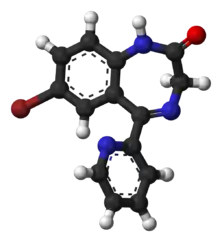

Bromazepam is a "classical" benzodiazepine; other classical benzodiazepines include: diazepam, clonazepam, oxazepam, lorazepam, nitrazepam, flurazepam, and clorazepate.[14] Its molecular structure is composed of a diazepine connected to a benzene ring and a pyridine ring, the benzene ring having a single nitrogen atom that replaces one of the carbon atoms in the ring structure.[15] It is a 1,4-benzodiazepine, which means that the nitrogens on the seven-sided diazepine ring are in the 1 and 4 positions.

Bromazepam binds to the GABA receptor GABAA, causing a conformational change and increasing the inhibitory effects of GABA. It acts as a positive modulator, increasing the receptors' response when activated by GABA itself or an agonist (such as alcohol). As opposed to barbital, BZDs are not GABA-receptor activators and rely on increasing the neurotransmitter's natural activity.[16] Bromazepam is an intermediate-acting benzodiazepine, is moderately lipophilic compared to other substances of its class[17] and metabolised hepatically via oxidative pathways.[18] It does not possess any antidepressant or antipsychotic qualities.[19]

After night time administration of bromazepam a highly significant reduction of gastric acid secretion occurs during sleep followed by a highly significant rebound in gastric acid production the following day.[20]

Bromazepam alters the electrical status of the brain causing an increase in beta activity and a decrease in alpha activity in EEG recordings.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

Bromazepam is reported to be metabolized by a hepatic enzyme belonging to the Cytochrome P450 family of enzymes. In 2003, a team led by Oda Manami at Oita Medical University reported that CYP3A4, a member of the Cytochrome P450 family, was not the responsible enzyme since itraconazole, a known inhibitor of CYP3A4, did not affect its metabolism.[22] In 1995, J. van Harten at the Solvay Pharmaceutical Department of Clinical Pharmacology in Weesp reported that fluvoxamine, which is a potent inhibitor of CYP1A2, a less potent CYP3A4 inhibitor, and a negligible inhibitor of CYP2D6, does inhibit its metabolism.[23]

The major metabolite of bromazepam is hydroxybromazepam,[22] which is an active agent too and has a half-life approximately equal to that of bromazepam.

Side-effects

Bromazepam is similar in side effects to other benzodiazepines. The most common side effects reported are drowsiness, sedation, ataxia, memory impairment, and dizziness.[24] Impairments to memory functions are common with bromazepam and include a reduced working memory and reduced ability to process environmental information.[25][26][27] A 1975 experiment on healthy, male college students exploring the effects of four different drugs on learning capacity observed that taking bromazepam alone at 6 mg 3 times daily for 2 weeks impaired learning capacities significantly. In combination with alcohol, impairments in learning capacity became even more pronounced.[28] Various studies report impaired memory, visual information processing and sensory data and impaired psychomotor performance;[29][30][31] deterioration of cognition including attention capacity and impaired co-ordinative skills;[32][33] impaired reactive and attention performance, which can impair driving skills;[34] drowsiness and decrease in libido.[35][36] Unsteadiness after taking bromazepam is, however, less pronounced than other benzodiazepines such as lorazepam.[37]

On occasion, benzodiazepines can induce extreme alterations in memory such as anterograde amnesia and amnesic automatism, which may have medico-legal consequences. Such reactions occur usually only at the higher dose end of the prescribing spectrum.[38]

Very rarely, dystonia can develop.[39]

Up to 30% treated on a long-term basis develop a form of dependence, i.e. these patients cannot stop the medication without experiencing physical and/or psychological benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.

Leukopenia and liver-damage of the cholestatic type with or without jaundice (icterus) have additionally been seen; the original manufacturer Roche recommends regular laboratory examinations to be performed routinely.

Ambulatory patients should be warned that bromazepam may impair the ability to drive vehicles and to operate machinery. The impairment is worsened by consumption of alcohol, because both act as central nervous system depressants. During the course of therapy, tolerance to the sedative effect usually develops.

Frequency and seriousness of adverse effects

As with all medication, the frequency and seriousness of side-effects varies greatly depending on quantities consumed.[40][41] In a study about bromazepam's negative effects on psychomotor skills and driving ability, it was noted that 3 mg doses caused minimal impairment.[42] It also appeared that impairment may be tied to methods of testing more so than on the product's intrinsic activity.[43]

Moreover, side-effects other than drowsiness, dizziness and ataxia seem to be rare[44] and not experienced by more than a few percent of users. The use of other, comparable medication seems to display an identically moderate side-effect profile.[45][46][47]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

Prolonged use of bromazepam can cause tolerance and may lead to both physical and psychological dependence on the drug, and as a result, it is a medication which is controlled by international law. It is nonetheless important to note that dependence, long-term use and misuse occur in a minority of cases[48][49][50] and are not representative of most patients' experience with this type of medication.[51][52]

It shares with other benzodiazepines the risk of abuse, misuse, psychological dependence or physical dependence.[53][54] A withdrawal study demonstrated both psychological dependence and physical dependence on bromazepam including marked rebound anxiety after 4 weeks chronic use. Those whose dose was gradually reduced experienced no withdrawal.[55]

Patients treated with bromazepam for generalised anxiety disorder were found to experience withdrawal symptoms such as a worsening of anxiety, as well as the development of physical withdrawal symptoms when abruptly withdrawn bromazepam.[56] Abrupt or over rapid withdrawal from bromazepam after chronic use even at therapeutic prescribed doses can lead to a severe withdrawal syndrome including status epilepticus and a condition resembling delerium tremens.[57][58][59]

Animal studies have shown that chronic administration of diazepam (or bromazepam) causes a decrease in spontaneous locomotor activity, decreased turnover of noradrenaline and dopamine and serotonin, increased activity of tyrosine hydroxylase and increased levels of the catecholamines. During withdrawal of bromazepam or diazepam a fall in tryptophan, serotonin levels occurs as part of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[60] Changes in the levels of these chemicals in the brain can cause headaches, anxiety, tension, depression, insomnia, restlessness, confusion, irritability, sweating, dysphoria, dizziness, derealization, depersonalization, numbness/tingling of extremities, hypersensitivity to light, sound, and smell, perceptual distortions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, appetite loss, hallucinations, delirium, seizures, tremor, stomach cramps, myalgia, agitation, palpitations, tachycardia, panic attacks, short-term memory loss, and hyperthermia.[61][62]

Overdose

Bromazepam is commonly involved in drug overdoses.[63] A severe bromazepam benzodiazepine overdose may result in an alpha pattern coma type.[64] The toxicity of bromazepam in overdosage increases when combined with other CNS depressant drugs such as alcohol or sedative hypnotic drugs.[65] Similarly to other benzodiazepines however, being a positive modulator of certain neuroreceptors and not an agonist, the product has reduced overdose potential compared to older products of the barbiturate class. Its consumption alone is very seldom fatal in healthy adults.[66][67]

Bromazepam was in 2005 the most common benzodiazepine involved in intentional overdoses in France.[68] Bromazepam has also been responsible for accidental poisonings in companion animals. A review of benzodiazepine poisonings in cats and dogs from 1991-1994 found bromazepam to be responsible for significantly more poisonings than any other benzodiazepine.[69]

Contraindications

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in elderly, pregnant, child, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[70]

Special populations

- Globally, bromazepam is contraindicated and should be used with caution in women who are pregnant, the elderly, patients with a history of alcohol or other substance abuse disorders and children.

- In 1987, a team of scientists led by Ochs reported that the elimination half-life, peak serum concentration, and serum free fraction are significantly elevated and the oral clearance and volume of distribution significantly lowered in elderly subjects.[71] The clinical consequence is that the elderly should be treated with lower doses than younger patients.

- Bromazepam may affect driving and ability to operate machinery.[72]

- Bromazepam is pregnancy category D, a classification that means that bromazepam has been shown to cause harm to the unborn child. The Hoffman LaRoche product information leaflet warns against breast feeding while taking bromazepam. There has been at least one report of sudden infant death syndrome linked to breast feeding while consuming bromazepam.[73][74]

Interactions

Cimetidine, fluvoxamine and propranolol causes a marked increase in the elimination half-life of bromazepam leading to increased accumulation of bromazepam.[71][75][23]

Society and culture

Drug misuse

Bromazepam has a similar misuse risk as other benzodiazepines such as diazepam.[76] In France car accidents involving psychotropic drugs in combination with alcohol (itself a major contributor) found benzodiazepines, mainly diazepam, nordiazepam, and bromazepam, to be the most common drug present in the blood stream, almost twice that of the next-most-common drug cannabis.[77] Bromazepam has also been used in serious criminal offences including robbery, homicide, and sexual assault.[78][79][80]

Brand names

It is marketed under several brand names, including, Brozam, Lectopam, Lexomil, Lexotan, Lexilium, Lexaurin, Brazepam, Rekotnil, Bromaze, Somalium, Lexatin, Calmepam, Zepam and Lexotanil.[81]

Legal status

Bromazepam is a Schedule IV drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[82]

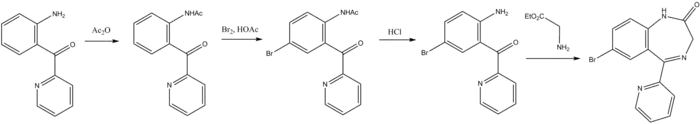

Synthesis

References

- "LEXOTAN (bromazepam) Product Insert" (PDF). Roche. 23 October 2012.

- "Bromazepam". Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Australian Government - Department of Health. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 53X. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "Content Not Available". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Podiwinsky F, Jellinger K (March 1979). "[Bromazepam in the treatment of somatized psychogenic disorders (author's transl)]" [Bromazepam in the treatment of somatized psychogenic disorders]. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift (in German). 91 (7): 240–244. PMID 34934.

- Laxenaire M, Kahn JP, Marchand P (May 1982). "[A clinical trial of bromazepam (author's transl)]" [A clinical trial of bromazepam]. La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French). 11 (22): 1699–1701. PMID 6124936.

- Ropert R, Bernes J, Dachary JM (1987). "[Efficacy and tolerance of alprazolam and bromazepam in flexible doses. Double-blind study in 119 ambulatory anxious patients]" [Efficacy and tolerance of alprazolam and bromazepam in flexible doses. Double-blind study in 119 ambulatory anxious patients]. L'Encéphale (in French). 13 (2): 89–95. PMID 2885173.

- Hallett C, Dean BC (11 August 2008). "Bromazepam: acute benefit-risk assessment in general practice". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 8 (10): 683–688. doi:10.1185/03007998409110117. PMID 6144455.

- "Bromazépam" (PDF). Haute Autorité de santé (HAS) (in French). 7 September 2016.

- "Bromazepam".

- "Bromazépam". Répertoire des Spécialités Pharmaceutiques. ANSM: Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (French: National Security Agency of Medicines and Health Products).

- Chweh AY, Lin YB, Swinyard EA (April 1984). "Hypnotic action of benzodiazepines: a possible mechanism". Life Sciences. 34 (18): 1763–1768. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(84)90576-9. PMID 6145073.

- Cordingley GJ, Dean BC, Hallett C (11 August 2008). "A multi-centre, double-blind parallel trial of bromazepam ('Lexotan') and lorazepam to compare the acute benefit-risk ratio in the treatment of patients with anxiety". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 9 (7): 505–510. doi:10.1185/03007998509109625. PMID 2863089.

- Braestrup C, Squires RF (April 1978). "Pharmacological characterization of benzodiazepine receptors in the brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 48 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90085-7. PMID 639854.

- Bromazepam Eutimia.com - Salud Mental. © 1999-2002.

- Poisbeau P, Gazzo G, Calvel L (11 September 2018). "Anxiolytics targeting GABAA receptors: Insights on etifoxine". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 19 (sup1): S36–S45. doi:10.1080/15622975.2018.1468030. PMID 30204559.

- Adeyemo MA, Idowu SO (25 November 2016). "Correlation of lipophilicity descriptors with pharmacokinetic parameters of selected benzodiazepines". African Journal of Biomedical Research. 19 (3): 213–218.

- Oelschläger H (July 1989). "[Chemical and pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepines]". Schweizerische Rundschau Fur Medizin Praxis (in German). 78 (27–28): 766–772. PMID 2570451.

- Amphoux G, Agussol P, Girard J (May 1982). "[The action of bromazepam on anxiety (author's transl)]" [The action of bromazepam on anxiety]. La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French). 11 (22): 1738–1740. PMID 6124947.

- Stacher G, Stärker D (February 1974). "Inhibitory effect of bromazepam on basal and betazole-stimulated gastric acid secretion in man". Gut. 15 (2): 116–120. doi:10.1136/gut.15.2.116. PMC 1412901. PMID 4820635.

- Fink M, Weinfeld RE, Schwartz MA, Conney AH (August 1976). "Blood levels and electroencephalographic effects of diazepam and bromazepam". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 20 (2): 184–191. doi:10.1002/cpt1976202184. PMID 7375. S2CID 38155674.

- Oda M, Kotegawa T, Tsutsumi K, Ohtani Y, Kuwatani K, Nakano S (November 2003). "The effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bromazepam in healthy volunteers". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 59 (8–9): 615–619. doi:10.1007/s00228-003-0681-4. PMID 14517708. S2CID 24131632.

- van Harten J (1995). "Overview of the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 29 (Suppl 1): 1–9. doi:10.2165/00003088-199500291-00003. PMID 8846617. S2CID 71812133.

- "LECTOPAM®". RxMed. RxMed. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Münte TF, Gehde E, Johannes S, Seewald M, Heinze HJ (1996). "Effects of alprazolam and bromazepam on visual search and verbal recognition memory in humans: a study with event-related brain potentials". Neuropsychobiology. 34 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1159/000119291. PMID 8884760.

- Montenegro M, Veiga H, Deslandes A, Cagy M, McDowell K, Pompeu F, et al. (June 2005). "[Neuromodulatory effects of caffeine and bromazepam on visual event-related potential (P300): a comparative study]". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 63 (2B): 410–415. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2005000300009. PMID 16059590.

- Cunha M, Portela C, Bastos VH, Machado D, Machado S, Velasques B, et al. (December 2008). "Responsiveness of sensorimotor cortex during pharmacological intervention with bromazepam". Neuroscience Letters. 448 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.024. PMID 18938214. S2CID 22491979.

- Liljequist R, Linnoila M, Mattila MJ, Saario I, Seppälä T (October 1975). "Effect of two weeks' treatment with thioridazine, chlorpromazine, sulpiride and bromazepam, alone or in combination with alcohol, on learning and memory in man". Psychopharmacologia. 44 (2): 205–208. doi:10.1007/BF00421011. PMID 710. S2CID 36415883.

- Stacher G, Bauer P, Brunner H, Grünberger J (January 1976). "Gastric acid secretion, serum-gastrin levels and psychomotor function under the influence of placebo, insulin-hypoglycemia, and/or bromazepam". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmacy. 13 (1): 1–10. PMID 2560.

- Bourin M, Auget JL, Colombel MC, Larousse C (1989). "Effects of single oral doses of bromazepam, buspirone and clobazam on performance tasks and memory". Neuropsychobiology. 22 (3): 141–145. doi:10.1159/000118609. PMID 2577220.

- Puga F, Sampaio I, Veiga H, Ferreira C, Cagy M, Piedade R, Ribeiro P (December 2007). "The effects of bromazepam on the early stage of visual information processing (P100)". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 65 (4A): 955–959. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2007000600006. PMID 18094853.

- Saario I (April 1976). "Psychomotor skills during subacute treatment with thioridazine and bromazepam, and their combined effects with alcohol". Annals of Clinical Research. 8 (2): 117–123. PMID 7178.

- Jansen AA, Verbaten MN, Slangen JL (1988). "Acute effects of bromazepam on signal detection performance, digit symbol substitution test and smooth pursuit eye movements". Neuropsychobiology. 20 (2): 91–95. doi:10.1159/000118481. PMID 2908134.

- Seppälä T, Saario I, Mattila MJ (1976). "Two Weeks' Treatment with Chlorpromazine, Thioridazine, Sulpiride, or Bromazepam: Actions and Interactions with Alcohol on Psychomotor Skills Related to Driving". Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. Modern Trends in Pharmacopsychiatry. Vol. 11. pp. 85–90. doi:10.1159/000399456. ISBN 978-3-8055-2349-3. PMID 9581.

- Horseau C, Brion S (May 1982). "[Clinical trial of bromazepam. Thirty-four cases (author's transl)]". La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French). 11 (22): 1741–1743. PMID 6124948.

- Perret J, Zagala A, Gaio JM, Hommel M, Meaulle F, Pellat J, Pollak P (May 1982). "[Bromazepam in anxiety. Clinical evaluation (author's transl)]". La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French). 11 (22): 1722–1724. PMID 6124942.

- Patat A, Foulhoux P (July 1985). "Effect on postural sway of various benzodiazepine tranquillizers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 20 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb02792.x. PMC 1400619. PMID 2862898.

- Rager P, Bénézech M (January 1986). "[Memory gaps and hypercomplex automatisms after a single oral dose of benzodiazepines: clinical and medico-legal aspects]" [Memory gaps and hypercomplex automatisms after a single oral dose of benzodiazepines: clinical and medico-legal aspects]. Annales Médico-Psychologiques (in French). 144 (1): 102–109. PMID 2876672.

- Pérez Trullen JM, Modrego Pardo PJ, Vázquez André M, López Lozano JJ (January 1992). "Bromazepam-induced dystonia". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 46 (8): 375–376. doi:10.1016/0753-3322(92)90306-r. PMID 1292648.

- "LEXOMIL - Bromazépam - Posologie, Effets secondaires, Grossesse".

- "How to Manage Common Drug Side Effects".

- Hobi V, Dubach UC, Skreta M, Forgo I, Riggenbach H (25 June 2016). "The subacute effect of bromazepam on psychomotor activity and subjective mood". The Journal of International Medical Research. 10 (3): 140–146. doi:10.1177/030006058201000302. PMID 6124470. S2CID 25165191.

- Hobi V, Dubach UC, Skreta M, Forgo J, Riggenbach H (25 June 2016). "The effect of bromazepam on psychomotor activity and subjective mood". The Journal of International Medical Research. 9 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1177/030006058100900201. PMID 6112173. S2CID 21899896.

- "Side effect information for Bromazepam".

- "Side effect information for Lorazepam".

- "Side effect information for Diazepam".

- "Notice patient - LORAZEPAM MYLAN 1 mg, comprimé pelliculé sécable - Base de données publique des médicaments".

- Yen CF, Ko CH, Chang YP, Yu CY, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. (September 2015). "Dependence, misuse, and beliefs regarding use of hypnotics by elderly psychiatric patients taking zolpidem, estazolam, or flunitrazepam". Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 7 (3): 298–305. doi:10.1111/appy.12147. PMID 25296384. S2CID 5782780.

- Schmidt LG, Grohmann R, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Otto M, Rüther E, Wolf B (June 1989). "Prevalence of benzodiazepine abuse and dependence in psychiatric in-patients with different nosology. An assessment of hospital-based drug surveillance data". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 154 (6): 839–843. doi:10.1192/bjp.154.6.839. PMID 2574611.

- Airagnes G, Lemogne C, Renuy A, Goldberg M, Hoertel N, Roquelaure Y, et al. (May 2019). "Prevalence of prescribed benzodiazepine long-term use in the French general population according to sociodemographic and clinical factors: findings from the CONSTANCES cohort". BMC Public Health. 19 (1): 566. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6933-8. PMC 6518636. PMID 31088561.

- Soyka M (June 2017). "Treatment of Benzodiazepine Dependence" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (24): 2399–2400. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1705239. PMID 28614686.

- HealthDay News (3 January 2019). "Prevalence of Benzodiazepine Use 12.6 Percent in the United States". Psychiatry Advisor. Haymarket.

- Rastogi RB, Lapierre YD, Singhal RL (1978). "Some neurochemical correlates of "rebound" phenomenon observed during withdrawal after long-term exposure to 1, 4-benzodiazepines". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology. 2 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1016/0364-7722(78)90021-8. PMID 31644.

- Laux G (May 1979). "[A case of Lexotanil dependence. Case report on tranquilizer abuse]". Der Nervenarzt. 50 (5): 326–327. PMID 37451.

- Fontaine R, Chouinard G, Annable L (July 1984). "Rebound anxiety in anxious patients after abrupt withdrawal of benzodiazepine treatment". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (7): 848–852. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.7.848. PMID 6145363.

- Chouinard G, Labonte A, Fontaine R, Annable L (1983). "New concepts in benzodiazepine therapy: rebound anxiety and new indications for the more potent benzodiazepines". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 7 (4–6): 669–673. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(83)90043-X. PMID 6141609. S2CID 32967696.

- Böning J (May 1981). "[Bromazepam withdrawal delirium - a psychopharmacological contribution to clinical withdrawal syndromes (author's transl)]". Der Nervenarzt. 52 (5): 293–297. PMID 6113557.

- Thomas P, Lebrun C, Chatel M (March 1993). "De novo absence status epilepticus as a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome". Epilepsia. 34 (2): 355–358. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02421.x. PMID 8384109. S2CID 45915803.

- Fukuda M, Nakajima N, Tomita M (January 1999). "Generalized tonic-clonic seizures following withdrawal of therapeutic dose of bromazepam". Pharmacopsychiatry. 32 (1): 42–43. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979188. PMID 10071183.

- Agarwal RA, Lapierre YD, Rastogi RB, Singhal RL (May 1977). "Alterations in brain 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism during the 'withdrawal' phase after chronic treatment with diazepam and bromazepam". British Journal of Pharmacology. 60 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb16740.x. PMC 1667179. PMID 18243.

- Professor Heather Ashton (2002). "Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw".

- O'Connor RD (1993). "Benzodiazepine dependence--a treatment perspective and an advocacy for control". NIDA Research Monograph. 131: 266–269. PMID 8105385.

- Gandolfi E, Andrade M (December 2006). "[Drug-related toxic events in the state of São Paulo, Brazil]" [Drug-related toxic events in the state of São Paulo, Brazil]. Revista de Saude Publica (in Portuguese). 40 (6): 1056–1064. doi:10.1590/s0034-89102006000700014. PMID 17173163.

- Pasinato E, Franciosi A, De Vanna M (1983). "["Alpha pattern coma" after poisoning with flunitrazepam and bromazepam. Case description]". Minerva Psichiatrica. 24 (2): 69–74. PMID 6140613.

- Marrache F, Mégarbane B, Pirnay S, Rhaoui A, Thuong M (October 2004). "Difficulties in assessing brain death in a case of benzodiazepine poisoning with persistent cerebral blood flow". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 23 (10): 503–505. doi:10.1191/0960327104ht478cr. PMID 15553176. S2CID 19380042.

- Löscher W, Rogawski MA (December 2012). "How theories evolved concerning the mechanism of action of barbiturates". Epilepsia. 53 (Suppl 8): 12–25. doi:10.1111/epi.12025. PMID 23205959. S2CID 4675696.

- Koyama K, Shimazu Y, Kikuno T, Kaziwara H, Sekiguti H (January 2003). "[Pharmacokinetics of bromazepam in 57 patients with acute drug intoxication]" [Pharmacokinetics of bromazepam in 57 patients with acute drug intoxication]. Chudoku Kenkyu (in Japanese). 16 (1): 51–56. PMID 12712542.

- Staikowsky F, Theil F, Candella S (July 2005). "[Trends in the pharmaceutical profile of intentional drug overdoses seen in the emergency room]" [Trends in the pharmaceutical profile of intentional drug overdoses seen in the emergency room]. Presse Médicale (in French). 34 (12): 842–846. doi:10.1016/s0755-4982(05)84060-6. PMID 16097205.

- Bertini S, Buronfosse F, Pineau X, Berny P, Lorgue G (December 1995). "Benzodiazepine poisoning in companion animals". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 37 (6): 559–562. PMID 8588297.

- Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Ochs HR, Greenblatt DJ, Friedman H, Burstein ES, Locniskar A, Harmatz JS, Shader RI (May 1987). "Bromazepam pharmacokinetics: influence of age, gender, oral contraceptives, cimetidine, and propranolol". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 41 (5): 562–570. doi:10.1038/clpt.1987.72. PMID 2882883. S2CID 1099919.

- Hobi V, Kielholz P, Dubach UC (October 1981). "[The effect of bromazepam on fitness to drive (author's transl)]" [The effect of bromazepam on fitness to drive]. MMW, Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 123 (42): 1585–1588. PMID 6118830.

- Hoffman LaRoche Pharmaceuticals (3 April 2008). "NAME OF THE MEDICINE LEXOTAN". Australia: roche-australia.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Martens PR (June 1994). "A sudden infant death like syndrome possibly induced by a benzodiazepine in breast-feeding". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1 (2): 86–87. doi:10.1097/00063110-199406000-00008. PMID 9422145.

- Perucca E, Gatti G, Spina E (September 1994). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 27 (3): 175–190. doi:10.2165/00003088-199427030-00002. PMID 7988100. S2CID 22472247.

- Woods JH (March 1984). "Progress report on the stimulant-depressant abuse liability evaluation project". NIDA Research Monograph. 49: 59–62. PMID 6148695.

- Staub C, Lacalle H, Fryc O (May 1994). "[Presence of psychotropic drugs in the blood of drivers responsible for car accidents, and who consumed alcohol at the same time]" [Presence of psychotropic drugs in the blood of drivers responsible for car accidents, and who consumed alcohol at the same time]. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin (in French). 39 (3): 143–149. doi:10.1007/BF01299658. PMID 8048274. S2CID 19379856.

- Brinkmann B, Fechner G, Püschel K (December 1984). "Identification of mechanical asphyxiation in cases of attempted masking of the homicide". Forensic Science International. 26 (4): 235–245. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(84)90028-8. PMID 6519613.

- de Boisjolly JM, Rougé-Maillart C, Roy PM, Roussel B, Turcant A, Delhumeau A (August 2003). "[Chemical submission]" [Chemical submission]. Presse Médicale (in French). 32 (26): 1216–1218. PMID 14506459.

- Djezzar S, Questel F, Burin E, Dally S (May 2009). "Chemical submission: results of 4-year French inquiry". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 123 (3): 213–219. doi:10.1007/s00414-008-0291-x. PMID 18925406. S2CID 23902799.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- List of psychotropic substances under international control Archived December 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board.

- Sanal (8 January 2012). "Synthesis Of Drugs: Laboratory Synthesis Of Bromazepam".

External links

- Bromazepam drug information from Lexi-Comp. Includes dosage information and a comprehensive list of international brand names.

- Inchem - Bromazepam

- LEXOTAN product information leaflet from Roche Pharmaceuticals