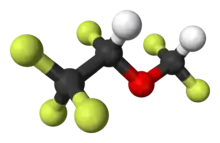

Desflurane

Desflurane (1,2,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether) is a highly fluorinated methyl ethyl ether used for maintenance of general anesthesia. Like halothane, enflurane, and isoflurane, it is a racemic mixture of (R) and (S) optical isomers (enantiomers). Together with sevoflurane, it is gradually replacing isoflurane for human use, except in economically undeveloped areas, where its high cost precludes its use. It has the most rapid onset and offset of the volatile anesthetic drugs used for general anesthesia due to its low solubility in blood.

-Desfluran_Structural_Formula_V1.svg.png.webp) | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | des-FLOO-rane |

| Trade names | Suprane |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Inhalation |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Not metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | Elimination dependent on minute ventilation |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.214.382 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C3H2F6O |

| Molar mass | 168.038 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Some drawbacks of desflurane are its low potency, its pungency and its high cost (though at low flow fresh gas rates, the cost difference between desflurane and isoflurane appears to be insignificant[1]). It may cause tachycardia and airway irritability when administered at concentrations greater than 10 vol%. Due to this airway irritability, desflurane is infrequently used to induce anesthesia via inhalation techniques.

Though it vaporizes very readily, it is a liquid at room temperature. Anaesthetic machines are fitted with a specialized anaesthetic vaporiser unit that heats liquid desflurane to a constant temperature. This enables the agent to be available at a constant vapor pressure, negating the effects fluctuating ambient temperatures would otherwise have on its concentration imparted into the fresh gas flow of the anesthesia machine.

Desflurane, along with enflurane and to a lesser extent isoflurane, has been shown to react with the carbon dioxide absorbent in anesthesia circuits to produce detectable levels of carbon monoxide through degradation of the anesthetic agent. The CO2 absorbent Baralyme, when dried, is most culpable for the production of carbon monoxide from desflurane degradation, although it is also seen with soda lime absorbent as well. Dry conditions in the carbon dioxide absorbent are conducive to this phenomenon, such as those resulting from high fresh gas flows.[2]

Pharmacology

As of 2005 the exact mechanism of the action of general anaesthetics has not been delineated.[3] Desflurane is known to act as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA and glycine receptors,[4][5][6] and as a negative allosteric modulator of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor,[7][8] as well as affecting other ligand-gated ion channels.[9][10]

Stereochemistry

Desflurane medications are a racemate of two enantiomers.[11]

| Enantiomeres of desflurane | |

|---|---|

-Desfluran_Structural_Formula_V1.svg.png.webp) (R)-Enantiomer |

-Desfluran_Structural_Formula_V1.svg.png.webp) (S)-Enantiomer |

Physical properties

| Boiling point : | 23.5 °C or 74.3 °F | (at 1 atm) | |

| Density : | 1.465 g/cm3 | (at 20 °C) | |

| Molecular Weight : | 168 | ||

| Vapor pressure: | 88.5 kPa | 672 mmHg | (at 20 °C) |

| 107 kPa | 804 mmHg | (at 24 °C) | |

| Blood:Gas partition coefficient: | 0.42 | ||

| Oil:Gas partition coefficient : | 19 | ||

| MAC : | 6 vol % | ||

Global-warming potential

Desflurane is a greenhouse gas. The twenty-year global-warming potential, GWP(20), for desflurane is 3714,[12] meaning that one tonne of desflurane emitted is equivalent to 3714 tonnes of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, much higher than sevoflurane or isoflurane. In addition to global warming potentials, drug potency and fresh gas flow rates must be considered for meaningful comparisons between anesthetic gases. When a steady state hourly amount of anesthetic necessary for 1 minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) at 2 liters per minute (LPM) for Sevoflurane, and 1 LPM for Desflurane and Isoflurane is weighted by the GWP, the clinically relevant quantities of each anesthetic can then be compared. On a per-MAC-hour basis, the total life cycle GHG impact of desflurane is more than 20 times higher than Isoflurane and Sevoflurane (1 minimal alveolar concentration-hour).[13] One paper finds anesthesia gases used globally contribute the equivalent of 1 million cars to global warming.[14] This estimate is commonly cited as a reason to neglect pollution prevention by anesthesiologists, however this is problematic. This estimate is extrapolated from only one U.S. institution's anesthetic practices, and this institution uses virtually no Desflurane. Researchers neglected to include nitrous oxide in their calculations, and reported an erroneous average of 17 kg CO2e per anesthetic. However, institutions that utilize some Desflurane and account for nitrous oxide have reported an average of 175–220 kg CO2e per anesthetic. Sulbaek-Anderson's group therefore likely underestimated the total worldwide contribution of inhaled anesthetics, and yet still advocates for inhaled anesthetic emissions prevention.[15]

References

- John Varkey (2012). "Cost Analysis of Desflurane and Sevoflurane: An Integrative Review and Implementation Project Introducing the Volatile Anesthetic Cost Calculator" (PDF).

- Fang; et al. (1995). "Carbon Monoxide Production from Degradation of Desflurane" (PDF). Anesthesia and Analgesia.

- Perkins B (7 February 2005). "How does anesthesia work?". Scientific American. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Hugh C. Hemmings; Philip M. Hopkins (2006). Foundations of Anesthesia: Basic Sciences for Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0-323-03707-0.

- Ronald D. Miller; Lars I. Eriksson; Lee A. Fleisher; Jeanine P. Wiener-Kronish; Neal H. Cohen; William L. Young (20 October 2014). Miller's Anesthesia. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 624–. ISBN 978-0-323-28011-2.

- Koichi Nishikawa & Neil L. Harrison (2003). "The actions of sevoflurane and desflurane on the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor type A: effects of TM2 mutations in the alpha and beta subunits". Anesthesiology. 99 (3): 678–684. doi:10.1097/00000542-200309000-00024. PMID 12960553. S2CID 72907404.

- Allan P. Reed; Francine S. Yudkowitz (2 December 2013). Clinical Cases in Anesthesia. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-323-18654-4.

- Paul Barash; Bruce F. Cullen; Robert K. Stoelting; Michael Cahalan; Christine M. Stock; Rafael Ortega (7 February 2013). Clinical Anesthesia, 7e: Print + Ebook with Multimedia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 470–. ISBN 978-1-4698-3027-8.

- Charles J. Coté; Jerrold Lerman; Brian J. Anderson (2013). A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children: Expert Consult – Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 499–. ISBN 978-1-4377-2792-0.

- Linda S. Aglio; Robert W. Lekowski; Richard D. Urman (8 January 2015). Essential Clinical Anesthesia Review: Keywords, Questions and Answers for the Boards. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-1-107-68130-9.

- Rote Liste Service GmbH (Hrsg.): Rote Liste 2017 - Arzneimittelverzeichnis für Deutschland (einschließlich EU-Zulassungen und bestimmter Medizinprodukte). Rote Liste Service GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, 2017, Aufl. 57, ISBN 978-3-946057-10-9, S. 175.

- Ryan, Susan M.; Nielsen, Claus J. (July 2010). "Global Warming Potential of Inhaled Anesthetics: Application to Clinical Use". Anesthesia & Analgesia. San Francisco, CA: International Anesthesia Research Society. 111 (1): 92–98. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181e058d7. PMID 20519425. S2CID 20737354. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- Sherman J, Le C, Lamers V, Eckelman M (May 2012). "Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Anesthetic Drugs". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 114 (5): 1086–1090. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824f6940. PMID 22492186. S2CID 207134715.

- Sulbaek Andersen MP, Sander SP, Nielsen OJ, Wagner DS, Sanford Jr TJ, Wallington TJ (July 2010). "Inhalation anaesthetics and climate change". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 105 (6): 760–766. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq259. PMID 20935004.

- Sherman, J. "Estimate of Carbon Dioxide Equivalents of Inhaled Anesthetics in the United States". American Society of Anesthesiologists. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

Further reading

- Eger, Eisenkraft, Weiskopf. The Pharmacology of Inhaled Anesthetics. 2003.

- Rang, Dale, Ritter, Moore. Pharmacology 5th Edition. 2003.

- Martin Bellgardt: Evaluation der Sedierungstiefe und der Aufwachzeiten frisch operierter Patienten mit neurophysiologischem Monitoring im Rahmen der Studie: Desfluran versus Propofol zur Sedierung beatmeter Patienten. Bochum, Dissertation, 2005 (pdf)

- Susanne Lohmann: Verträglichkeit, Nebenwirkungen und Hämodynamik der inhalativen Sedierung mit Desfluran im Rahmen der Studie: Desfluran versus Propofol zur Sedierung beatmeter Patienten. Bochum, Dissertation, 2006 (pdf Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine)

- Patel SS, Goa KL (1995). "Desflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its efficacy in general anaesthesia". Drugs. 50 (4): 742–67. doi:10.2165/00003495-199550040-00010. PMID 8536556.

External links

- "Desflurane". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.