Etomidate

Etomidate[2] (USAN, INN, BAN; marketed as Amidate) is a short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent used for the induction of general anaesthesia and sedation[3] for short procedures such as reduction of dislocated joints, tracheal intubation, cardioversion and electroconvulsive therapy. It was developed at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1964 and was introduced as an intravenous agent in 1972 in Europe and in 1983 in the United States.[4]

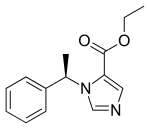

(R)-etomidate ethyl ester | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Amidate, Hypnomidate, Tomvi |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 76% |

| Metabolism | Ester hydrolysis in plasma and liver |

| Elimination half-life | 75 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine (85%) and Bile duct (15%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.046.700 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H16N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 244.294 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 67 °C (153 °F) |

| Boiling point | 392 °C (738 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

The most common side effects include venous pain on injection and skeletal muscle movements.[5]

Medical uses

Sedation and anesthesia

In emergency settings, etomidate can be used as a sedative hypnotic agent. It is used for conscious sedation[6][7] and as a part of a rapid sequence induction to induce anaesthesia.[8][9] It is used as an anaesthetic agent since it has a rapid onset of action and a safe cardiovascular risk profile, and therefore is less likely to cause a significant drop in blood pressure than other induction agents.[10][11] In addition, etomidate is often used because of its easy dosing profile, limited suppression of ventilation, lack of histamine liberation and protection from myocardial and cerebral ischemia.[9] Thus, etomidate is a good induction agent for people who are hemodynamically unstable.[8] Etomidate also has interesting characteristics for people with traumatic brain injury because it is one of the only anesthetic agents able to decrease intracranial pressure and maintain a normal arterial pressure.[4][12][13][14][15]

In those with sepsis, one dose of the medication does not appear to affect the risk of death.[16]

Speech and memory test

Another use for etomidate is to determine speech lateralization in people prior to performing lobectomies to remove epileptogenic centres in the brain. This is called the etomidate speech and memory test, or eSAM, and is used at the Montreal Neurological Institute.[17][18] However, only retrospective cohort studies support the use and safety of etomidate for this test.[19]

Steroidogenesis inhibitor

In addition to its action and use as an anesthetic, etomidate has also been found to directly inhibit the enzymatic biosynthesis of steroid hormones, including corticosteroids in the adrenal gland.[20][21] As the only adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitor available for intravenous or parenteral administration, it is useful in situations in which rapid control of hypercortisolism is necessary or in which oral administration is unfeasible.[20][21][22]

Use in executions

The U.S. state of Florida used the drug in a death penalty procedure when Mark James Asay, 53, was executed on August 24, 2017. He became the first person in the U.S. to be executed with etomidate as one of the drugs. Etomidate replaces midazolam as the sedative. Drug companies have made it harder to buy midazolam for executions. The etomidate was followed by rocuronium bromide, a paralytic, and finally, potassium acetate in place of the commonly used potassium chloride injection to stop the heart. Potassium acetate was first used for this purpose inadvertently in a 2015 execution in Oklahoma.[23]

Adverse effects

Etomidate suppresses corticosteroid synthesis in the adrenal cortex by reversibly inhibiting 11β-hydroxylase, an enzyme important in adrenal steroid production; it leads to primary adrenal suppression.[24][25] Using a continuous etomidate infusion for sedation of critically ill trauma patients in intensive care units has been associated with increased mortality due to adrenal suppression.[26] Continuous intravenous administration of etomidate leads to adrenocortical dysfunction. The mortality of patients exposed to a continuous infusion of etomidate for more than 5 days increased from 25% to 44%, mainly due to infectious causes such as pneumonia.[26]

Because of etomidate-induced adrenal suppression, its use for patients with sepsis is controversial. Cortisol levels have been reported to be suppressed up to 72 hours after a single bolus of etomidate in this population at risk for adrenal insufficiency.[9] For this reason, many authors have suggested that etomidate should never be used for critically ill patients with septic shock[27][28][29] because it could increase mortality.[29][30] However, other authors continue to defend etomidate's use for septic patients because of etomidate's safe hemodynamic profile and lack of clear evidence of harm.[12][31] A study by Jabre et al. showed that a single dose of etomidate used for Rapid Sequence Induction prior to endrotracheal intubation has no effect on mortality compared to ketamine even though etomidate did cause transient adrenal suppression.[32] In addition, a recent meta-analysis done by Hohl could not conclude that etomidate increased mortality.[9] The authors of this meta-analysis concluded more studies were needed because of lack of statistical power to conclude definitively about the effect of etomidate on mortality. Thus, Hohl suggests a burden to prove etomidate is safe for use in septic patients, and more research is needed before it is used.[9] Other authors[33][34][35] advise giving a prophylactic dose of steroids (e.g. hydrocortisone) if etomidate is used, but only one small prospective controlled study[35] in patients undergoing colorectal surgery has verified the safety of giving stress dose corticosteroids to all patients receiving etomidate.

In a retrospective review of almost 32,000 people, etomidate, when used for the induction of anaesthesia, was associated 2.5-fold increase in the risk of dying compared with those given propofol.[36] People given etomidate also had significantly greater odds of having cardiovascular morbidity and significantly longer hospital stay.[36] These results, especially given the large size of study, strongly suggest that, at the very least, clinicians should use etomidate judiciously.[36] However, given this is a retrospective study, it is clearly misinterpreting how etomidate is typically used: etomidate is a drug that is reserved for sicker patients whom may not tolerate the more severe hemodynamic liability (towards lower mean pressures) and, thus the bias of this retrospective study is inconclusive, at best.

In people with traumatic brain injury, etomidate use is associated with a blunting of an ACTH stimulation test.[25] The clinical impact of this effect has yet to be determined.

In addition, concurrent use of etomidate with opioids and/or benzodiazepines, is hypothesized to exacerbate etomidate-related adrenal insufficiency.[37][38] However, only retrospective evidence of this effect exists and prospective studies are needed to measure the clinical impact of this interaction.

Etomidate is associated with a high incidence of burning on injection, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and superficial thrombophlebitis (with rates higher than propofol).[39]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

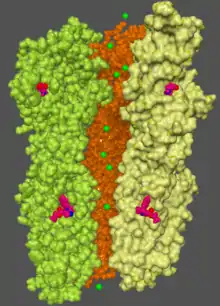

(R)-Etomidate is tenfold more potent than its (S)-enantiomer. At low concentrations (R)-etomidate is a modulator at GABAA receptors[41] containing β2 and β3[42] subunits. At higher concentrations, it can elicit currents in the absence of GABA and behaves as an allosteric agonist. Its binding site is located in the transmembrane section of this receptor between the beta and alpha subunits (β+α−). β3-containing GABAA receptors are involved in the anesthetic actions of etomidate, while the β2-containing receptors are involved in some of the sedation and other actions that can be elicited by this drug.[43]

Pharmacokinetics

At the typical dose, anesthesia is induced for the duration of about 5–10 minutes, though the half-life of drug metabolism is about 75 minutes, because etomidate is redistributed from the plasma to other tissues.

- Onset of action: 30–60 seconds

- Peak effect: 1 minute

- Duration: 3–5 minutes; terminated by redistribution

- Distribution: Vd: 2–4.5 L/kg

- Protein binding: 76%

- Metabolism: Hepatic and plasma esterases

- Half-life distribution: 2.7 minutes

- Half-life redistribution: 29 minutes

- Half-life elimination: 2.9 to 5.3 hours[4]

Metabolism

Etomidate is highly protein-bound in blood plasma and is metabolised by hepatic and plasma esterases to inactive products. It exhibits a biexponential decline.

Formulation

Etomidate is usually presented as a clear colourless solution for injection containing 2 mg/ml of etomidate in an aqueous solution of 35% propylene glycol, although a lipid emulsion preparation (of equivalent strength) has also been introduced. Etomidate was originally formulated as a racemic mixture,[44] but the R form is substantially more active than its enantiomer.[45] It was later reformulated as a single-enantiomer drug, becoming the first general anesthetic in that class to be used clinically.[46]

References

Citations

- "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Tomvi". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- US Patent 3354173 'Imidazole carboxylates'

- Vinson DR, Bradbury DR (June 2002). "Etomidate for procedural sedation in emergency medicine". Ann Emerg Med. 39 (6): 592–8. doi:10.1067/mem.2002.123695. PMID 12023700.

- Bergen, JM; Smith, DC (1998). "A review of etomidate for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department". J Emerg Med. 15 (2): 221–230. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(96)00350-2. PMID 9144065.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: December 22, 2020". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 22 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Di Liddo, L; D'Angelo, A; Nguyen, B; Bailey, B; Amre, D; Stanciu, C (2006). "Etomidate versus midazolam for procedural sedation in pediatric outpatients: a randomized controlled trial". Ann Emerg Med. 48 (4): 433–440. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.004. PMID 16997680.

- Miner, JR; Danahy, M; Moch, A; Biros, M (2007). "Randomized clinical trial of etomidate versus propofol for procedural sedation in the emergency department". Ann Emerg Med. 49 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.042. PMID 16997421.

- Sivilotti, ML; Filbin, MF; Murray, HE; Slasor, P; Walls, RM; Near, Investigators (2003). "Does the sedative agent facilitate emergency rapid sequence intubation?". Acad Emerg Med. 10 (6): 612–620. doi:10.1197/aemj.10.6.612. PMID 12782521.

- Hohl, CM; Kelly-Smith, CH; Yeug, TC; Sweet, DD; Doyle-Waters, MM; Schulzer, M (2010). "The effect of a bolus dose of etomidate on cortisol levels, mortality, and health services utilization: a systematic review". Ann Emerg Med. 56 (2): 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.030. PMID 20346542.

- Zed, PJ; Abu-Laban, RB; Harrison, DW. (2006). "Intubating conditions and hemodynamic effects of etomidate for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department: an observational cohort study". Acad Emerg Med. 13 (4): 378–83. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb00313.x. PMID 16531603.

- Sokolove, PE; Price, DD; Okada, P. (2000). "The safety of etomidate for emergency rapid sequence intubation of pediatric patients". Pediatr Emerg Care. 16 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1097/00006565-200002000-00005. PMID 10698137. S2CID 24913220.

- Walls, RM; Murphy, MF; Schneider, RE (2000). "Manual of emergency airway management".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Marx, J (2002). "Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wadbrook, PS (2000). "Advances in airway pharmacology. Emerging trends and evolving controversy". Emerg Med Clin North Am. 18 (4): 767–788. doi:10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70158-9. PMID 11130938.

- Yeung, JK; Zed, PJ (2002). "A review of etomidate for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department". CJEM. 4 (3): 194–198. doi:10.1017/S1481803500006370. PMID 17609005.

- Gu, WJ; Wang, F; Tang, L; Liu, JC (Sep 25, 2014). "Single-Dose Etomidate Does Not Increase Mortality in Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies". Chest. 147 (2): 335–346. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1012. PMID 25255427.

- Jones-Gotman, M; Sziklas, V; Djordjevic, J (2009). "Intracarotid amobarbital procedure and etomidate speech and memory test". Can J Neurol Sci. 36 Suppl 2: S51–4. PMID 19760903.

- Jones-Gotman, M; Sziklas, V; Djordjevic, J; Dubeau, F; Gotman, J; Angle, M; Tampieri, D; Olivier, A; Andermann, F (2005). "Etomidate speech and memory test (eSAM): a new drug and improved intracarotid procedure". Neurology. 65 (11): 1723–1729. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187975.78433.cb. PMID 16344513. S2CID 1835535.

- Patel, Akta; Wordell, Cindy; Szarlej, Dorota (2011). "Alternatives to sodium amobarbital in the Wada test". Ann Pharmacother. 45 (3): 395–401. doi:10.1345/aph.1P476. PMID 21325100. S2CID 207264114.

- Terry F. Davies (2015). A Case-Based Guide to Clinical Endocrinology. Springer. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-4939-2059-4.

- J. Larry Jameson; Leslie J. De Groot (2015). Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 250–. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2.

- McGrath M, Ma C, Raines D (2017). "Dimethoxy-etomidate: A Non-hypnotic Etomidate Analog that Potently Inhibits Steroidogenesis". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 364 (2): 229–237. doi:10.1124/jpet.117.245332. PMC 5783534. PMID 29203576.

- Jason Dearon. "Florida executes convicted killer Mark Asay using new drug". Sun Sentinel.

- Wagner, RL; White, PF; Kan, PB; Rosenthal, MH; Feldman, D. (1984). "Inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis by the anesthetic etomidate". N Engl J Med. 310 (22): 1415–21. doi:10.1056/NEJM198405313102202. PMID 6325910.

- Archambault, P; Dionne, CE; Lortie, G; LeBlanc, F; Rioux, A; Larouche, G (September 2012). "Adrenal inhibition following a single dose of etomidate in intubated traumatic brain injury victims". CJEM. 14 (5): 270–82. doi:10.2310/8000.2012.110560. PMID 22967694.

- Ledingham, IM; Watt, I (1983). "Influence of sedation in critically ill multiple trauma patients". Lancet. 1 (8336): 1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92712-5. PMID 6134053. S2CID 305277.

- Morris, C; McAllister, C (2005). "Etomidate for emergency anaesthesia; mad, bad and dangerous to know?". Anaesthesia. 60 (8): 737–740. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04325.x. PMID 16029220. S2CID 27825801.

- Jackson, WL (2005). "Should we use etomidate as an induction agent for endotracheal intubation in patients with septic shock? A critical appraisal". Chest. 127 (3): 1031–1038. doi:10.1378/chest.127.3.1031. PMID 15764790.

- Annane, D; Sebille, V; Bellissant, E (2006). "Exploring the role of etomidate in septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome". Crit Care Med. 34 (6): 1858–1859. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000220048.38438.40. PMID 16715011.

- Cuthbertson, BH; Sprung, CL; Annane, D; Chevret, S; Garfield, M; Goodman, S; Laterre, PF; Vincent, JL; et al. (2009). "The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock". Intensive Care Med. 35 (1): 1868–1876. doi:10.1007/s00134-009-1603-4. PMID 19652948. S2CID 24371957.

- Murray, H; Marik, PE (2005). "Etomidate for endotracheal intubation in sepsis: acknowledging the good while accepting the bad". Chest. 127 (3): 707–709. doi:10.1378/chest.127.3.707. PMID 15764747.

- Jabre, P; Combes, X; Laposttolle, F; Dhaouadi, M; Ricard-Hibon, A; Vivien, B; Bertrand, L; Beltramini, A; et al. (2009). "Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomized controlled trial". Lancet. 374 (9686): 293–300. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60949-1. PMID 19573904. S2CID 52230993.

- Den Brinker, M; Joosten, KF; Liem, O; de Jong, FH; Hop, WC; Hazelzet, JA; van Dijk, M; Hokken-Koelega, AC. (2005). "Adrenal insufficiency in meningococcal sepsis: bioavailable cortisol levels and impact of interleukin-6 levels and intubation with etomidate on adrenal function and mortality". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 90 (9): 5110–7. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1107. PMID 15985474.

- Schulz-Stubner, S (2005). "Sedation in traumatic brain injury: Avoid etomidate". Crit Care Med. 33 (11): 2723. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000187093.71107.a8. PMID 16276231.

- Stuttmann, R; Allolio, B; Becker, A (1988). "etomidate versus etomidate and hydrocortisone for anesthesia induction in abdominal surgical interventions". Anaesthesist. 37 (9): 576–582. PMID 3056084.

- Komatsu, R; You, J; Mascha, EJ; Sessler, DI; Kasuya, Y; Turan, A (December 2013). "Anesthetic induction with etomidate, rather than propofol, is associated with increased 30-day mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 117 (6): 1329–37. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e318299a516. PMID 24257383. S2CID 23165849.

- Daniell, Harry (2008). "Opioid and benzodiazepine contributions to etomidate-associated adrenal insufficiency". Intensive Care Medicine. 34 (11): 2117–8. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1264-8. PMID 18795258. S2CID 36288054.

- Daniell, HW (2008). "Opioid contribution to decreased cortisol levels in critical care patients". Arch Surg. 143 (12): 1147–1148. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.12.1147. PMID 19075164.

- Kosarek L, et al. Increase in Venous Complications Associated With Etomidate Use During a Propofol Shortage: An Example of Clinically Important Adverse Effects Related to Drug Substitution. The Ochsner Journal. 2011;11:143-146.

- Kim JJ, Gharpure A, Teng J, Zhuang Y, Howard RJ, Zhu S, Noviello CM, Walsh RM, Lindahl E, Hibbs RE (2020). "Shared structural mechanisms of general anaesthetics and benzodiazepines". Nature. 585 (7824): 303–308. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2654-5. PMC 7486282. PMID 32879488.

- Vanlersberghe, C; Camu, F (2008). Etomidate and other non-barbiturates. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 182. pp. 267–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_13. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. PMID 18175096.

- Drexler, B; Jurd, R; Rudolph, U; Antkowiak, B (2009). "Distinct actions of etomidate and propofol at beta3-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors". Neuropharmacology. 57 (4): 446–55. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.014. PMID 19555700. S2CID 26796180.

- Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Miller KW, Cohen JB (2012). "Mapping general anesthetic binding site(s) in human α1β3 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with [³H]TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive etomidate analogue". Biochemistry. 51 (4): 836–47. doi:10.1021/bi201772m. PMC 3274767. PMID 22243422.

- International Non-Proprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Preparations – Rec. I.N.N. List 6

- Servin, Frédérique S.; Sear, John W. (2011). "Chapter 27. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous anesthetics". In Evers, Alex S.; Maze, Mervyn; Kharasch, Evan D. (eds.). Anesthetic Pharmacology: Basic Principles and Clinical Practice (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Tomlin, Sarah L.; Jenkins, Andrew; Lieb, William R.; Franks, Nicholas P. (1998). "Stereoselective Effects of Etomidate Optical Isomers on Gamma‐aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors and Animals". Anesthesiology. 88 (3): 708–717. doi:10.1097/00000542-199803000-00022. PMID 9523815. S2CID 11665790.

Sources

- Cotton, B. A.; Guillamondegui, O. D.; Fleming, S. B.; Carpenter, R. O.; Patel, S. H.; Morris, J. A.; Arbogast, P. G. (2008). "Increased risk of adrenal insufficiency following etomidate exposure in critically injured patients". Arch Surg. 143 (1): 62–7. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.1.62. PMID 18209154.; discussion 67.

- Den Brinker, M.; Hokken-Koelega, A. C.; Hazelzet, J. A.; Hop, W. C.; Joosten, K. F.; Joosten, KF (2008). "One single dose of etomidate negatively influences adrenocortical performance for at least 24 h in children with meningococcal sepsis". Intensive Care Med. 34 (1): 163–8. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0836-3. PMC 2668631. PMID 17710382.

- Marik, P. E.; Pastores, S. M.; Annane, D.; et al. (2008). "Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American College of Critical Care Medicine". Crit Care Med. 36 (6): 1937–49. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817603ba. PMID 18496365. S2CID 7861625.

- Mullins, M. E.; Theodoro, D. L. (2008). "Lack of evidence for adrenal insufficiency after single-dose etomidate". Arch Surg. 143 (8): 808–9. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.8.808-c. PMID 18711047.; author reply 809.

- Sacchetti, A. (2008). "Etomidate: not worth the risk in septic patients". Ann Emerg Med. 52 (1): 14–6. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.001. PMID 18565379.

- Sprung, C. L.; Annane, D.; Keh, D.; et al. (2008). "Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock". N Engl J Med. 358 (2): 111–24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa071366. PMID 18184957.

- Tekwani, K.; Watts, H.; Chan, C.; Rzechula, K.; Nanini, S.; Kulstad, E. (2008). "The effect of single-bolus etomidate on septic patient mortality: a retrospective review". West J Emerg Med. 9 (4): 195–200. PMC 2672284. PMID 19561744.

- Tekwani, K. L.; Watts, H. F.; Rzechula, K. H.; Sweis, R. T.; Kulstad, E. B. (2009). "A prospective observational study of the effect of etomidate on septic patient mortality and length of stay". Acad Emerg Med. 16 (1): 11–4. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00299.x. PMID 19055676.

- Vinclair, M.; Broux, C.; Faure, P.; Brun, J.; Genty, C.; Jacquot, C.; Chabre, O.; Payen, J. F. (2008). "Duration of adrenal inhibition following a single dose of etomidate in critically ill patients". Intensive Care Med. 34 (4): 714–9. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0970-y. PMID 18092151. S2CID 23538535.

External links

- "Etomidate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.