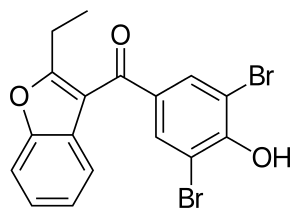

Benzbromarone

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H12Br2O3 |

| Molar mass | 424.088 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 161 to 163 °C (322 to 325 °F) |

SMILES

| |

Benzbromarone is a medication used in the treatment of gout.[1][2] Its benefits are similar to allopurinal and likely better than probenecid.[2] It may be used when allopurinol, the first-line treatment, fails or produces intolerable side effects. Onset of effects is in a few weeks.[1]

About 1 in 1000 people develop liver problems, which generally occur after more than a month of use.[1] It is a nonpurine inhibitor of xanthine oxidase.[1] It is structurally related to the antiarrhythmic amiodarone.[1][3]

Benzbromarone has been approved for medical use in parts of Europe and Asia in the 1970s.[1][4] It has never been approved in the United States due to concerns regarding side effects.[1]

Mechanism of action

Benzbromarone is a very potent inhibitor of CYP2C9.[3][5] Several analogues of the drug have been developed as CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 inhibitors for use in research.[6][7]

History

Benzbromarone was introduced in the 1970s and was viewed as having few associated serious adverse reactions. It was registered in about 20 countries throughout Europe, Asia and South America.

In 2003, the drug was withdrawn by Sanofi-Synthélabo, after reports of serious hepatotoxicity, although it is still marketed in several countries by other drug companies.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Benzbromarone". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- 1 2 Kydd, Alison SR; Seth, Rakhi; Buchbinder, Rachelle; Edwards, Christopher J; Bombardier, Claire (2014-11-14). "Uricosuric medications for chronic gout". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD010457. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010457.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 25392987.

- 1 2 Kumar V, Locuson CW, Sham YY, Tracy TS (October 2006). "Amiodarone analog-dependent effects on CYP2C9-mediated metabolism and kinetic profiles". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 34 (10): 1688–96. doi:10.1124/dmd.106.010678. PMID 16815961.

- 1 2 Lee MH, Graham GG, Williams KM, Day RO (2008). "A benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone in the treatment of gout. Was its withdrawal from the market in the best interest of patients?". Drug Safety. 31 (8): 643–65. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831080-00002. PMID 18636784. S2CID 1204662.

- ↑ Hummel MA, Locuson CW, Gannett PM, Rock DA, Mosher CM, Rettie AE, Tracy TS (September 2005). "CYP2C9 genotype-dependent effects on in vitro drug-drug interactions: switching of benzbromarone effect from inhibition to activation in the CYP2C9.3 variant". Molecular Pharmacology. 68 (3): 644–51. doi:10.1124/mol.105.013763. PMC 1552103. PMID 15955872.

- ↑ Locuson CW, Rock DA, Jones JP (June 2004). "Quantitative binding models for CYP2C9 based on benzbromarone analogues". Biochemistry. 43 (22): 6948–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.127.2015. doi:10.1021/bi049651o. PMID 15170332.

- ↑ Locuson CW, Suzuki H, Rettie AE, Jones JP (December 2004). "Charge and substituent effects on affinity and metabolism of benzbromarone-based CYP2C19 inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (27): 6768–76. doi:10.1021/jm049605m. PMID 15615526.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|