Meropenem

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Merrem, others |

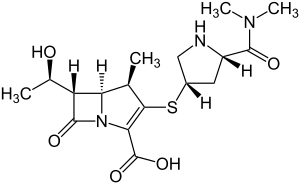

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antibiotic (carbapenem)[1] |

| Main uses | Meningitis, intra-abdominal infection, pneumonia, sepsis, anthrax[1] |

| Side effects | Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, headache, rash, pain at site of injection[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

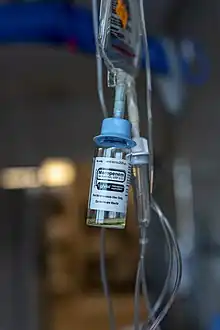

| Routes of use | Intravenous |

| Defined daily dose | 3 gram[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Protein binding | Approximately 2% |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

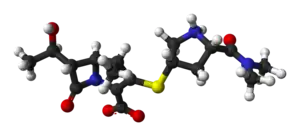

| Formula | C17H25N3O5S |

| Molar mass | 383.46 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Meropenem, sold under the brandname Merrem among others, is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat a variety of bacterial infections.[1] Some of these include meningitis, intra-abdominal infection, pneumonia, sepsis, and anthrax.[1] It is given by injection into a vein.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, constipation, headache, rash, and pain at the site of injection.[1] Serious side effects include Clostridium difficile infection, seizures, and allergic reactions including anaphylaxis.[1] Those who are allergic to other β-lactam antibiotics are more likely to be allergic to meropenem as well.[1] Use in pregnancy appears to be safe.[1] It is in the carbapenem family of medications.[1] Meropenem usually results in bacterial death through blocking their ability to make a cell wall.[1] It is more resistant to breakdown by β-lactamase producing bacteria.[1]

Meropenem was patented in 1983.[3] It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between 3.44 and 20.58 USD per one gram vial as of 2015.[5] In the United Kingdom this amount costs the NHS about £16 in 2015.[6]

Medical uses

It is in the 'watch' group of the WHO AWaRe Classification.[7]

The spectrum of action includes many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (including Pseudomonas) and anaerobic bacteria. The overall spectrum is similar to that of imipenem, although meropenem is more active against Enterobacteriaceae and less active against Gram-positive bacteria. It works against extended-spectrum β-lactamases, but may be more susceptible to metallo-β-lactamases.[8] Meropenem is frequently given in the treatment of febrile neutropenia. This condition frequently occurs in patients with hematological malignancies and cancer patients receiving anticancer drugs that suppress bone marrow formation. It is approved for complicated skin and skin structure infections, complicated intra-abdominal infections and bacterial meningitis.

In 2017 the FDA granted approval for the combination of meropenem and vaborbactam to treat adults with complicated urinary tract infections.[9]

Administration

Meropenem is administered intravenously as a white crystalline powder to be dissolved in 5% monobasic potassium phosphate solution. Dosing must be adjusted for altered kidney function and for haemofiltration.[10]

As with other ß-lactams antibiotics, the effectiveness of treatment depends on the amount of time during the dosing interval that the meropenem concentration is above the minimum inhibitory concentration for the bacteria causing the infection.[11] For ß-lactams, including meropenem, prolonged intravenous administration is associated with lower mortality than bolus intravenous infusion in persons with whose infections are severe, or caused by bacteria that are less sensitive to meropenem, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[11][12]

Dosage

It is generally used at a dose of 500 mg to 1 gram every 8 hours.[1]

The defined daily dose is 3 gram (by injection).[2]

Side effects

The most common adverse effects are diarrhea (4.8%), nausea and vomiting (3.6%), injection-site inflammation (2.4%), headache (2.3%), rash (1.9%) and thrombophlebitis (0.9%).[13] Many of these adverse effects were observed in severely ill individuals already taking many medications including vancomycin.[14][15] Meropenem has a reduced potential for seizures in comparison with imipenem. Several cases of severe hypokalemia have been reported.[16][17] Meropenem, like other carbapenems, is a potent inducer of multidrug resistance in bacteria.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Meropenem is bactericidal except against Listeria monocytogenes, where it is bacteriostatic. It inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis like other β-lactam antibiotics. In contrast to other beta-lactams, it is highly resistant to degradation by β-lactamases or cephalosporinases. In general, resistance arises due to mutations in penicillin-binding proteins, production of metallo-β-lactamases, or resistance to diffusion across the bacterial outer membrane.[13] Unlike imipenem, it is stable to dehydropeptidase-1, so can be given without cilastatin.

In 2016, a synthetic peptide-conjugated PMO (PPMO) was found to inhibit the expression of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, an enzyme that many drug-resistant bacteria use to destroy carbapenems.[18][19]

Society and culture

Trade names

| Country | Name | Maker |

|---|---|---|

| India | Inzapenum | Dream India |

| Aurobindo Pharma | ||

| Penmer | Biocon | |

| Meronir | Nirlife | |

| Merowin | Strides Acrolab | |

| Aktimer | Aktimas Biopharmaceuticals | |

| Neopenem | Neomed | |

| Mexopen | Samarth life sciences | |

| Meropenia | SYZA Health Sciences LLP | |

| Ivpenem | Medicorp Pharmaceuticals | |

| Merofit | ||

| Lykapiper | Lyka Labs | |

| Winmero | Parabolic Drugs | |

| Bangladesh | Inpen | Navana pharma |

| I-Penam | Incepta | |

| Merocil | Pharmacil | |

| Indonesia | Merofen | Kalbe |

| Brazil | Zylpen | Aspen Pharma |

| Japan, Korea | Meropen | |

| Australia | Merem | |

| Taiwan | Mepem | |

| Germany | Meronem | |

| US | Meronem | AstraZeneca |

| ... | Merosan | Sanbe Farma |

| Merobat | Interbat | |

| Zwipen | ||

| Carbonem | ||

| Ronem | Opsonin Pharma, BD | |

| Neopenem | ||

| Merocon | Continental | |

| Carnem | Laderly Biotech | |

| Penro | Bosch | |

| Meroza | German Remedies | |

| Merotrol | Lupin) | |

| Meromer | Orchid Chemicals | |

| Mepenox | BioChimico | |

| Meromax | Eurofarma | |

| Ropen | Macter | |

| mirage | adwic | |

| Meropex | Apex Pharma Ltd. | |

| Merostarkyl | Hefny Pharma Group[20] |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Meropenem". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 497. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-09-17. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Single Drug Information". International Medical Products Price Guide. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ↑ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 379. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ Zanichelli, Veronica; Sharland, Michael; Cappello, Bernadette; Moja, Lorenzo; Getahun, Haileyesus; Pessoa-Silva, Carmem; Sati, Hatim; van Weezenbeek, Catharina; Balkhy, Hanan; Simão, Mariângela; Gandra, Sumanth; Huttner, Benedikt (1 April 2023). "The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 101 (4): 290–296. doi:10.2471/BLT.22.288614. ISSN 0042-9686. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ↑ AHFS Drug Information (2006 ed.). American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2006.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements - FDA approves new antibacterial drug". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ↑ Bilgrami, I; Roberts, JA; Wallis, SC; Thomas, J; Davis, J; Fowler, S; Goldrick, PB; Lipman, J (July 2010). "Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis receiving high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (7): 2974–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.01582-09. PMC 2897321. PMID 20479205. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- 1 2 Yu Z, Pang X, Wu X, Shan C, Jiang S (2018). "Clinical outcomes of prolonged infusion (extended infusion or continuous infusion) versus intermittent bolus of meropenem in severe infection: A meta-analysis". PLoS ONE. 13 (7): e0201667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201667. PMC 6066326. PMID 30059536.

- ↑ Vardakas KZ, Voulgaris GL, Maliaros A, Samonis G, Falagas ME (January 2018). "Prolonged versus short-term intravenous infusion of antipseudomonal β-lactams for patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". Lancet Infect Dis. 18 (1): 108–120. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30615-1. PMID 29102324.

- 1 2 Mosby's Drug Consult 2006 (16 ed.). Mosby, Inc. 2006.

- ↑ Erden, M; Gulcan, E; Bilen, A; Bilen, Y; Uyanik, A; Keles, M (7 March 2013). "Pancytopenýa and Sepsýs due to Meropenem: A Case Report" (PDF). Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 12 (1). doi:10.4314/tjpr.v12i1.21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "Meropenem side effects - from FDA reports". eHealthMe. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Margolin, L (2004). "Impaired rehabilitation secondary to muscle weakness induced by meropenem". Clinical Drug Investigation. 24 (1): 61–2. doi:10.2165/00044011-200424010-00008. PMID 17516692.

- ↑ Bharti, R; Gombar, S; Khanna, AK (2010). "Meropenem in critical care - uncovering the truths behind weaning failure". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 26 (1): 99–101. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- ↑ "New molecule knocks out superbugs' immunity to antibiotics". newatlas.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-22. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- ↑ K., Sully, Erin; L., Geller, Bruce; Lixin, Li; M., Moody, Christina; M., Bailey, Stacey; L., Moore, Amy; Michael, Wong; Patrice, Nordmann; M., Daly, Seth (2016). "Peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PPMO) restores carbapenem susceptibility to NDM-1-positive pathogens in vitro and in vivo". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 72 (3): 782–790. doi:10.1093/jac/dkw476. PMC 5890718. PMID 27999041.

- ↑ "Hefny Pharma Group". hefnypharmagroup.info. Archived from the original on 2018-05-23. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Meropenem". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2020-07-14.