Aztreonam

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Azactam, Cayston, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antibiotic |

| Main uses | Bone infections, endometritis, intra abdominal infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, sepsis[1] |

| Side effects | Pain at the site of injection, vomiting, rash[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation |

| Defined daily dose | 0.2 gram (inhalation) 4 gram (by injection)[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (IM) 0.1% (by mouth in rats) Unknown (by mouth in humans) |

| Protein binding | 56% |

| Metabolism | Liver (minor %) |

| Elimination half-life | 1.7 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

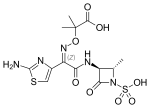

| Formula | C13H17N5O8S2 |

| Molar mass | 435.43 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 227 °C (441 °F) (dec.) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Aztreonam, sold under the brand name Azactam among others, is an antibiotic used primarily to treat infections caused by gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[1][3] This may include bone infections, endometritis, intra abdominal infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, sepsis, and gonorrhoea.[1][3] It is given by injection into a vein or muscle or breathed in as a mist.[1]

Common side effects when given by injection include pain at the site of injection, vomiting, and rash.[1] Common side effects when inhaled include wheezing, cough, and vomiting.[1] Serious side effects include Clostridium difficile infection and allergic reactions including anaphylaxis.[1] Those who are allergic to other β-lactam have a low rate of allergy to aztreonam.[1] Use in pregnancy appears to be safe.[1] It is in the monobactam family of medications.[1] It is a manufactured version of a chemical from the bacterium Chromobacterium violaceum.[4] Aztreonam usually results in bacterial death through blocking their ability to make a cell wall.[1]

Aztreonam was approved for medical use in the United States in 1986.[1] It was removed from the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines in 2019.[5][6] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the UK the injectable form costs the NHS about £35 per day while the inhaled form costs about £2,200 for a course of treatment, as of 2021.[3]

Medical uses

Nebulized forms of aztreonam are used to treat infections that are complications of cystic fibrosis and are approved for such use in Europe and the US; they are also used off-label for non-CF bronchiectasis, ventilator-associated pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mycobacterial disease, and to treat infections in people who have received lung transplants.[7]

Spectrum of activity

Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis are generally susceptible to aztreonam[8], while some bacteria have resistance toward it[9]. Furthermore, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter freundii have developed resistance to aztreonam to varying degrees.[10]Aztreonam is often used in people who are penicillin allergic or who cannot tolerate aminoglycosides.[11]

Aztreonam has strong activity against susceptible Gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa,[12] it is resistant to some beta-lactamases[13]

It has no useful activity against Gram-positive bacteria or anaerobes. It is known to be effective against a wide range of bacteria including Citrobacter, Enterobacter, E. coli, Haemophilus, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Serratia species.[14] The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms.[15]

- Staphylococcus aureus 8 - >128 μg/ml

- Staphylococcus epidermidis 8 - 32 μg/ml

- Streptococcus pyogenes 8 - ≥128 μg/ml

Synergism between aztreonam and arbekacin or tobramycin against P. aeruginosa has been suggested in a 1992 article[16]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 0.2 gram (inhalation) or 4 gram (by injection).[2]

Aztreonam is poorly absorbed when given by mouth, so it must be administered parenterally (as an intravenous or intramuscular injection, or inhaled using an ultrasonic nebulizer[17]).[18] In the United States, it was approved for inhalation in 2010, for the suppression of P. aeruginosa infections in people with cystic fibrosis.[19] It received conditional approval for administration in Canada and the European Union in 2009,[19] and has been fully approved in Australia.[20]

Side effects

Reported side effects include injection site reactions, rash, and rarely toxic epidermal necrolysis. Gastrointestinal side effects generally include diarrhea and nausea and vomiting. There may be drug-induced eosinophilia. Because of the unfused beta-lactam ring unique to aztreonam, there is somewhat lower cross-reactivity between aztreonam and many other beta-lactam antibiotics, and it may be safe to administer aztreonam to many patients with hypersensitivity (allergies) to penicillins and nearly all cephalosporins.[21] However, like other beta lactams, there is a risk of serious allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.[22] This is more likely if the patient is allergic to a certain cephalosporin known as ceftazidime. Aztreonam exhibits cross-reactivity with this cephalosporin due to a similar side chain.[23] [22]

Special caution is warranted in patients who are allergic to ceftazidime and are subsequently placed on aztreonam therapy.[24]

Mechanism of action

Aztreonam is similar in action to penicillin. It inhibits synthesis of the bacterial cell wall, by blocking peptidoglycan crosslinking. It has a very high affinity for penicillin-binding protein-3 and mild affinity for penicillin-binding protein-1a. Aztreonam binds the penicillin-binding proteins of Gram-positive and anaerobic bacteria very poorly and is largely ineffective against them.[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Aztreonam". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 "5. Infection". British National Formulary (BNF) (82 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2021 – March 2022. pp. 579–580. ISBN 978-0-85711-413-6.

- ↑ Yaffe, Sumner J.; Aranda, Jacob V. (2010). Neonatal and Pediatric Pharmacology: Therapeutic Principles in Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 438. ISBN 9780781795388. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). Executive summary: the selection and use of essential medicines 2019: report of the 22nd WHO Expert Committee on the selection and use of essential medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325773. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.05. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2019 (including the 21st WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 7th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330668. ISBN 9789241210300. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;1021.

- ↑ Quon BS, Goss CH, Ramsey BW (March 2014). "Inhaled antibiotics for lower airway infections". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 11 (3): 425–34. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201311-395fr. PMC 4028738. PMID 24673698.

- ↑ Dowd, Frank J.; Yagiela, John A.; Johnson, Bart; Mariotti, Angelo; Neidle, Enid A. (2010). Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 618. ISBN 978-0-323-07824-5. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ Asensio, Juan A.; Trunkey, Donald D. (2008). Current Therapy of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 693. ISBN 978-0-323-07086-7. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ Grayson, M. Lindsay; Cosgrove, Sara E.; Crowe, Suzanne; Hope, William; McCarthy, James S.; Mills, John; Mouton, Johan W.; Paterson, David L. Kucers' The Use of Antibiotics: A Clinical Review of Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiparasitic, and Antiviral Drugs, Seventh Edition - Three Volume Set. CRC Press. p. 645. ISBN 978-1-4987-4796-7. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ Paw, Henry; Shulman, Rob (2019). Handbook of Drugs in Intensive Care: An A-Z Guide. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-108-44435-4. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ↑ Doan, Trinh L.; Pollastri, Michael; Walters, Michael A.; Georg, Gunda I. (2011). "Chapter 23 - The Future of Drug Repositioning: Old Drugs, New Opportunities". Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 385–401. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ "Azactam". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ↑ Mosby's Drug Consult 2006 (16th ed.). Mosby, Inc. 2006.

- ↑ Amirkia, Vafa David; Qiubao, Pan (22 January 2011). "The Antimicrobial Index: a comprehensive literature-based antimicrobial database and reference work". Bioinformation. 5 (8): 365–366. ISSN 0973-2063. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Y.; Uchida, H.; Kawakami, Y. (December 1992). "Synergy with aztreonam and arbekacin or tobramycin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from blood". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 30 (6): 871–872. doi:10.1093/jac/30.6.871. ISSN 0305-7453. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ "Aztreonam Dosage Guide with Precautions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Ritter, James; Lewis, Lionel; Mant, Timothy; Ferro, Albert. A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 5Ed. CRC Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-4441-1300-6. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- 1 2 Larkin, Catherine (22 February 2010). "Gilead's Inhaled Antibiotic for Lungs Wins Approval". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ "FDA approves Gilead cystic fibrosis drug Cayston". BusinessWeek. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- 1 2 AHFS Drug Information 2006 (2006 ed.). American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2006.

- 1 2 "Aztreonam Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ Chaudhry, Saira B.; Veve, Michael P.; Wagner, Jamie L. (29 July 2019). "Cephalosporins: A Focus on Side Chains and β-Lactam Cross-Reactivity". Pharmacy: Journal of Pharmacy Education and Practice. 7 (3). doi:10.3390/pharmacy7030103. ISSN 2226-4787. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ James, Christopher W.; Gurk-Turner, Cheryle (2001). "Cross-reactivity of beta-lactam antibiotics". Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 14 (1): 106–107. ISSN 0899-8280. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

External links

- "Aztreonam". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

| Identifiers: |

|---|