Pivmecillinam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Low |

| Protein binding | 5 to 10% (as mecillinam) |

| Metabolism | Pivmecillinam is hydrolyzed to mecillinam |

| Elimination half-life | 1 to 3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal and biliary, mostly as mecillinam |

| Identifiers | |

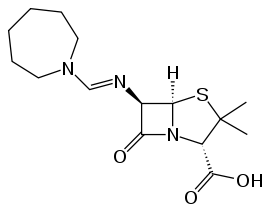

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.046.600 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H33N3O5S |

| Molar mass | 439.57 g·mol−1 |

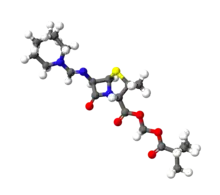

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

| | |

Pivmecillinam (INN) or amdinocillin pivoxil (USAN, trade names Selexid, Penomax and Coactabs) is an orally active prodrug of mecillinam, an extended-spectrum penicillin antibiotic. Pivmecillinam is the pivaloyloxymethyl ester of mecillinam.

Pivmecillinam is only considered to be active against Gram-negative bacteria, and is used primarily in the treatment of lower urinary tract infections. In the Nordic countries, it has been widely used in that indication since the 1970s. It has been proposed as the first-line drug of choice for empirical treatment of acute cystitis.[1][2] It has also been used to treat paratyphoid fever and shigellosis.[3]

Activity

Adverse effects

The adverse effect profile of pivmecillinam is similar to that of other penicillins. The most common side effects of mecillinam use are rash and gastrointestinal upset, including nausea and vomiting.[1][4]

Prodrugs that release pivalic acid when broken down by the body — such as pivmecillinam, pivampicillin and cefditoren pivoxil — have long been known to deplete levels of carnitine.[5][6] This is not due to the drug itself, but to pivalate, which is mostly removed from the body by forming a conjugate with carnitine. Although short-term use of these drugs can cause a marked decrease in blood levels of carnitine,[7] it is unlikely to be of clinical significance;[6] long-term use, however, appears problematic and is not recommended.[6][8][9]

References

- 1 2 3 Nicolle LE (August 2000). "Pivmecillinam in the treatment of urinary tract infections". J Antimicrob Chemother. 46 (Suppl A): 35–39. doi:10.1093/jac/46.suppl_1.35. PMID 10969050.

- ↑ Graninger W (October 2003). "Pivmecillinam—therapy of choice for urinary tract infection". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 22. Suppl 2: 73–8. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(03)00235-8. PMID 14527775.

- ↑ Tanphaichitra D, Srimuang S, Chiaprasittigul P, Menday P, Christensen OE (1984). "The combination of pivmecillinam and pivampicillin in the treatment of enteric fever". Infection. 12 (6): 381–3. doi:10.1007/BF01645219. PMID 6569851.

- ↑ "Selexid Tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. June 5, 2008. Retrieved on August 31, 2008.

- ↑ Holme E, Greter J, Jacobson CE, et al. (August 1989). "Carnitine deficiency induced by pivampicillin and pivmecillinam therapy". Lancet. 2 (8661): 469–73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92086-2. PMID 2570185.

- 1 2 3 Brass EP (December 2002). "Pivalate-generating prodrugs and carnitine homeostasis in man". Pharmacol Rev. 54 (4): 589–98. doi:10.1124/pr.54.4.589. PMID 12429869.

- ↑ Abrahamsson K, Holme E, Jodal U, Lindstedt S, Nordin I (June 1995). "Effect of short-term treatment with pivalic acid containing antibiotics on serum carnitine concentration—a risk irrespective of age". Biochem. Mol. Med. 55 (1): 77–9. doi:10.1006/bmme.1995.1036. PMID 7551831.

- ↑ Holme E, Jodal U, Linstedt S, Nordin I (September 1992). "Effects of pivalic acid-containing prodrugs on carnitine homeostasis and on response to fasting in children". Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 52 (5): 361–72. doi:10.3109/00365519209088371. PMID 1514015.

- ↑ Makino Y, Sugiura T, Ito T, Sugiyama N, Koyama N (September 2007). "Carnitine-associated encephalopathy caused by long-term treatment with an antibiotic containing pivalic acid". Pediatrics. 120 (3): e739–41. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0339. PMID 17724113.