Tigecycline

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌtaɪɡəˈsaɪkliːn/ |

| Trade names | Tygacil |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tetracycline antibiotic[2] |

| Main uses | Intra abdominal infections, pneumonia, skin and skin structure infections[2] |

| Side effects | Nausea, diarrhea, sunburns, pancreatitis, liver problems, anaphylaxis[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Intravenous (IV) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a614002 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Protein binding | 71–89% |

| Metabolism | Not metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 42.4 hours |

| Excretion | 59% Bile, 33% kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H39N5O8 |

| Molar mass | 585.658 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Tigecycline, sold under the brand name Tygacil, is a tetracycline antibiotic used for a number of bacterial infections.[2] This includes intra abdominal infections, pneumonia, and skin and skin structure infections.[2] Use is only recommended when other antibiotics are not suitable, as it is less effective.[5][2] It is given by injection into a vein.[5]

Common side effects include nausea and diarrhea.[2] Other side effects may include sunburns, pancreatitis, liver problems, Clostridioides difficile infection, and anaphylaxis.[2] Use during pregnancy may damage the babies bones or teeth.[2][6] It is a glycylcycline and works by blocking the bacteria’s ribosomes.[2][5]

Tigecycline was approved for medical use in the United States in 2005 and Europe in 2006.[7][5] It was removed from the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines in 2019.[8][9] The World Health Organization classifies it as critically important for human medicine.[10] It is available as a generic medication.[6] A five day course of treatment costs about 800 USD in the United States as of 2021.[11] In the United Kingdom this amount costs the NHS £290.[6]

Medical uses

Tigecycline is used to treat different kinds of bacterial infections, including complicated skin and structure infections, complicated intra-abdominal infections and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Tigecycline is a glycylcycline antibiotic that covers MRSA and Gram-negative organisms:

- Tigecycline can treat complicated skin and structure infections caused by; Escherichia coli, vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus grp., Streptococcus pyogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacteroides fragilis.[12]

- Tigecycline is indicated for treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections caused by; Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Streptococcus anginosus grp., Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides uniformis, Bacteroides vulgatus, Clostridium perfringens, and Peptostreptococcus micros.[12]

- Tigecycline may be used for treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia caused by; penicillin susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae that does not produce Beta-lactamase and Legionella pneumophila.[12]

Tigecycline is given intravenously and has activity against a variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens, many of which are resistant to existing antibiotics. Tigecycline successfully completed phase III trials in which it was at least equal to intravenous vancomycin and aztreonam to treat complicated skin and skin structure infections, and to intravenous imipenem and cilastatian to treat complicated intra-abdominal infections.[13] Tigecycline is active against many Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes – including activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (with MIC values reported at 2 µg/mL) and multi-drug resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. It has no activity against Pseudomonas spp. or Proteus spp. The drug is licensed for the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections as well as intra-abdominal infections.

The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infection recommends tigecycline as a potential salvage therapy for severe and/or complicated or refractory Clostridium difficile infection.[14]

Tigecycline can also be used in vulnerable populations such as immunocompromised patients or patients with cancer.[14] Tigecycline may also have potential for use in acute myeloid leukemia.[15]

Susceptibility data

Tigecycline targets both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria including a few key multi-drug resistant pathogens. The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few medically significant bacterial pathogens.

- Escherichia coli: 0.015 μg/mL — 4 μg/mL

- Klebsiella pneumoniae: 0.06 μg/mL — 16 μg/mL

- Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-resistant): 0.03 μg/mL — 2 μg/mL[16]

Tigecycline generally has poor activity against most strains of Pseudomonas.[17]

Liver or kidney problems

Tigecycline does not require dose adjustment for people with mild to moderate liver problems. However, in people with severe liver problems dosing should be decreased and closely monitored.[12]

Tigecycline does not require dose changes in people with poor kidney function or having hemodialysis.[12]

Dosage

It is given at an initial dose of 100 mg.[5] This is followed by 50 mg twice per day for 5 to 14 days.[5]

Side effects

As a tetracycline derivative, tigecycline exhibits similar side effects to the class of antibiotics. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are the most common reported side effect.[14]

Common side effects of tigecycline include nausea and vomiting.[19] Nausea (26%) and vomiting (18%) tend to be mild or moderate and usually occur during the first two days of therapy.[4]

Rare adverse effects (<2%) include: swelling, pain, and irritation at injection site, anorexia, jaundice, hepatic dysfunction, pruritus, acute pancreatitis, and increased prothrombin time.[4]

Precautions

Precaution is needed when taken in individuals with tetracycline hypersensitivity, pregnant women, and children. It has been found to cause fetal harm when administered during pregnancy and therefore is classified as pregnancy category D.[12] In rats or rabbits, tigecycline crossed the placenta and was found in the fetal tissues, and is associated with slightly lower birth weights as well as slower bone ossification. Even though it was not considered teratogenic, tigecycline should be avoided unless benefits outweigh the risks.[4] In addition, its use during childhood can cause yellow-grey-brown discoloration of the teeth and should not be used unless necessary.

More so, there are clinical reports of tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis, with particular relevance to patients also diagnosed with cystic fibrosis.[20]

Tigecycline showed an increased mortality in patients treated for hospital-acquired pneumonia, especially ventilator-associated pneumonia (a non-approved use), but also in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections, complicated intra-abdominal infections and diabetic foot infection.[4] Increased mortality was in comparison to other treatment of the same types of infections. The difference was not statistically significant for any type, but mortality was numerically greater for every infection type with Tigecycline treatment, and prompted a black box warning by the FDA.[21][22]

Black box warning

The FDA issued a black box warning in September 2010, for tigecycline regarding an increased risk of death compared to other appropriate treatment.[21][4][23] As a result of increase in total death rate (cause is unknown) in individuals taking this drug, tigecycline is reserved for situations in which alternative treatment is not suitable.[12][23] The FDA updated the black box warning in 2013.[22]

Interactions

Tigecycline has been found to interact with medications, such as:

- Warfarin: Since both tigecycline and warfarin bind to serum or plasma proteins, there is potential for protein-binding interactions, such that one drug will have more effect than the other. Although dose adjustment is not necessary, INR and prothrombin time should be monitored if given concurrently.[24]

- Oral contraceptives: Effectiveness of oral contraceptives are decreased with concurrent use due to reduction in the concentration levels of oral contraceptives.

However, the mechanism behind these drug interactions have not been fully analyzed.[4]

Mechanism of action

Tigecycline is broad-spectrum antibiotic that acts as a protein synthesis inhibitor. It exhibits bacteriostatic activity by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit of bacteria and thereby blocking the interaction of aminoacyl-tRNA with the A site of the ribosome.[25] In addition, tigecycline has demonstrated bactericidal activity against isolates of S. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila.[4]

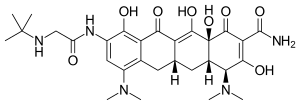

It is a third-generation tetracycline derivative within a class called glycylcyclines which carry a N,N-dimethyglycylamido (DMG) moiety attached to the 9-position of tetracycline ring D.[26] With structural modifications as a 9-DMG derivative of minocycline, tigecycline has been found to improve minimal inhibitory concentrations against Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, when compared to tetracyclines.[26]

Resistance mechanisms

Bacterial resistance towards tigecycline in Enterobacteriaceae (such as E. coli) is often caused by genetic mutations leading to an up-regulation of bacterial efflux pumps, such as the RND type efflux pump AcrAB. Some bacterial species such as Pseudomonas spp. can be naturally resistant to tigecycline through the constant over-expression of such efflux pumps. In some Enterobacteriaceae species, mutations in ribosomal genes such as rpsJ have been found to cause resistance to tigecycline.[27]

Pharmacokinetics

Tigecycline is metabolized through glucuronidation into glucuronide conjugates and N-acetyl-9-aminominocycline metabolite.[28] Therefore, dose adjustments are needed for patients with severe hepatic impairment.[4] More so, it is primarily eliminated unchanged in the feces and secondarily eliminated by the kidneys.[28] No renal adjustments are necessary.

History

It was developed in response to the growing rate of antibiotic resistant bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, and E. coli.[29]

Society and culture

Approval

It is approved to treat complicated skin and soft tissue infections (cSSTI), complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI), and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CAP) in individuals 18 years and older.[29][30][28][4] In the United Kingdom it is approved in adults and in children from the age of eight years for the treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections (excluding diabetic foot infections) and complicated intra-abdominal infections in situations where other alternative antibiotics are not suitable.[31]

Other names

- GAR-936[32]

- Tygacil

- Tigeplug (marketed by Biocon, India)

- Tigilyn (Marketed by Real Value therapy pharmaceuticals company in Myanmar, Manufactured by Lyka)

References

- ↑ "EP2181330". European Patent Office. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Tigecycline Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Tigecycline (Tygacil) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Tygacil- tigecycline injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution". DailyMed. 20 July 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Tygacil EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (in aragonés). Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 601. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- ↑ "Tigecycline Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). Executive summary: the selection and use of essential medicines 2019: report of the 22nd WHO Expert Committee on the selection and use of essential medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325773. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.05. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2019 (including the 21st WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 7th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330668. ISBN 9789241210300. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;1021.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine (6th revision ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/312266. ISBN 9789241515528.

- ↑ "Tigecycline Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "TYGACIL U.S. Physician Prescribing Information". Pfizer. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Scheinfeld N (2005). "Tigecycline: a review of a new glycylcycline antibiotic". Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 16 (4): 207–12. doi:10.1080/09546630510011810. PMID 16249141. S2CID 28869637.

- 1 2 3 Kaewpoowat, Quanhathai; Ostrosky-Zeichner, Luis (1 February 2015). "Tigecycline: a critical safety review". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 14 (2): 335–342. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.997206. ISSN 1474-0338. PMID 25539800. S2CID 43407481.

- ↑ Skrtić, M; Sriskanthadevan, S; Jhas, B; Gebbia, M; Wang, X; Wang, Z; Hurren, R; Jitkova, Y; Gronda, M; Maclean, N; Lai, CK; Eberhard, Y; Bartoszko, J; Spagnuolo, P; Rutledge, AC; Datti, A; Ketela, T; Moffat, J; Robinson, BH; Cameron, JH; Wrana, J; Eaves, CJ; Minden, MD; Wang, JC; Dick, JE; Humphries, K; Nislow, C; Giaever, G; Schimmer, AD (2011). "Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloid leukemia". Cancer Cell. 20 (5): 674–688. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.015. PMC 3221282. PMID 22094260.

- ↑ "Tigecycline : Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). Toku-e.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Tygacil [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals; 2005. Updated July 2010.

- ↑ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Berger, Timothy; Neuhaus, Isaac (12 April 2015). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin E-Book: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-323-31969-0. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ↑ Muralidharan, Gopal (January 2005). "Pharmacokinetics of tigecycline after single and multiple doses in healthy subjects". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 49 (1): 220–229. doi:10.1128/aac.49.1.220-229.2005. PMC 538906. PMID 15616299.

- ↑ Hemphill MT, Jones KR (2015). "Tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis in a cystic fibrosis patient: A case report and literature review". J Cyst Fibros. 15 (1): e9–11. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2015.07.008. PMID 26282838.

- 1 2 "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Increased risk of death with Tygacil (tigecycline) compared to other antibiotics used to treat similar infections". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- 1 2 "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of increased risk of death with IV antibacterial Tygacil (tigecycline) and approves new Boxed Warning". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 27 September 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- 1 2 Dixit, Deepali (6 March 2014). "The role of tigecycline in the treatment of infections in light of the new black box warning". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 12 (4): 397–400. doi:10.1586/14787210.2014.894882. PMID 24597542. S2CID 36614422.

- ↑ Zimmerman, James J.; Raible, Donald G.; Harper, Dawn M.; Matschke, Kyle; Speth, John L. (1 July 2008). "Evaluation of a Potential Tigecycline-Warfarin Drug Interaction". Pharmacotherapy. 28 (7): 895–905. doi:10.1592/phco.28.7.895. ISSN 1875-9114. PMID 18576904. S2CID 3474652.

- ↑ Tigecycline: A Novel Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial: Pharmacology and Mechanism of Action Archived 24 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine Christine M. Slover, PharmD, Infectious Diseases Fellow, Keith A. Rodvold, PharmD and Larry H. Danziger, PharmD, Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

- 1 2 Nguyen, Fabian (May 2014). "Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance mechanisms". Biol Chem. 395 (5): 559–75. doi:10.1515/hsz-2013-0292. PMID 24497223. S2CID 12668198.

- ↑ Pournaras, Spyros; Koumaki, Vasiliki; Spanakis, Nicholas; Gennimata, Vasiliki; Tsakris, Athanassios (2016). "Current perspectives on tigecycline resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: susceptibility testing issues and mechanisms of resistance". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 48 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.04.017. PMID 27256586.

- 1 2 3 Hoffman, Matthew (25 May 2007). "Metabolism, Excretion, and Pharmacokinetics of [14C]Tigecycline, a First-In-Class Glycylcycline Antibiotic, after Intravenous Infusion to Healthy Male Subjects". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 35 (9): 1543–1553. doi:10.1124/dmd.107.015735. PMID 17537869. S2CID 5070076.

- 1 2 Rose W, Rybak M (2006). "Tigecycline: first of a new class of antimicrobial agents". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (8): 1099–110. doi:10.1592/phco.26.8.1099. PMID 16863487. S2CID 29714610.

- ↑ Kasbekar N (2006). "Tigecycline: a new glycylcycline antimicrobial agent". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 63 (13): 1235–43. doi:10.2146/ajhp050487. PMID 16790575.

- ↑ "Tygacil 50mg powder for solution for infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". Medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Betriu C, Rodríguez-Avial I, Sánchez BA, Gómez M, Picazo JJ (2002). "Comparative in vitro activities of tigecycline (GAR-936) and other antimicrobial agents against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia". J Antimicrob Chemother. 50 (5): 758–59. doi:10.1093/jac/dkf196. PMID 12407139.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |