Cefazolin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /sɪˈfæzələn/[1] |

| Trade names | Ancef, Cefacidal, other |

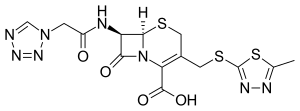

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | First-generation cephalosporin[2] |

| Main uses | Cellulitis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, endocarditis, joint infection, biliary tract infections[2] |

| Side effects | Diarrhea, vomiting, yeast infections, allergic reactions[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous, intramuscular |

| Defined daily dose | 3 grams[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | NA |

| Metabolism | ? |

| Elimination half-life | 1.8 hours (given IV) 2 hours (given IM) |

| Excretion | kidney, unchanged |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H14N8O4S3 |

| Molar mass | 454.50 g·mol−1 |

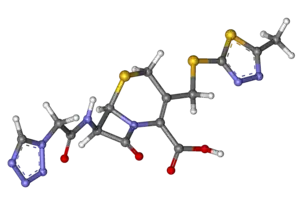

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 198 to 200 °C (388 to 392 °F) (dec.) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Cefazolin, also known as cefazoline and cephazolin, is an antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[2] Specifically it is used to treat cellulitis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, endocarditis, joint infection, and biliary tract infections.[2] It is also used to prevent group B streptococcal disease around the time of delivery and before surgery.[2] It does not treat MRSA.[4] It is typically given by injection into a muscle or vein.[2]

Common side effects include diarrhea, vomiting, yeast infections, and allergic reactions.[2] It is not recommended in people who have a history of anaphylaxis to penicillin.[5] It is relatively safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[2][6] Cefazolin is in the first-generation cephalosporin class of medication and works by interfering with the bacteria's cell wall.[2]

Cefazolin was patented in 1967 and came into commercial use in 1971.[7][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$1 to US$2 per day as of 2015.[10] In the United States, a course of treatment costs US$25 to US$50.[6] In the UK, ten 2 gram vials costs the NHS almost £200, as of 2021.[11]

Medical uses

Cefazolin is in the 'access' group of the WHO AWaRe Classification.[12]

It is used in a variety of infections provided that susceptible organisms are involved. It is indicated for use in the following infections:[13]

- Respiratory tract infections

- Urinary tract infections

- Skin infections

- Biliary tract infections

- Bone and joint infections

- Genital infections

- Blood infections (sepsis)

- Endocarditis

It can also be used peri-operatively to prevent infections post-surgery, and is often the preferred drug for surgical prophylaxis.[13]

There is no penetration into the central nervous system and therefore cefazolin is not effective in treating meningitis.[14]

Cefazolin has been shown to be effective in treating methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) but does not work in cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[13] In many instances of staphylococcal infections, such as bacteremia, cefazolin is an alternative to penicillin in patients who are allergic to penicillin.[14] However, there is still potential for a reaction to occur with cefazolin and other cephalosporins in patients allergic to penicillin.[13] Resistance to cefazolin is seen in several species of bacteria, such as Mycoplasma and Chlamydia, in which case different generations of cephalosporins may be more effective.[15] Cefazolin does not fight against Enterococcus, anaerobic bacteria or atypical bacteria among others.[14]

Bacterial susceptibility

As a first-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, cefazolin and other first-generation antibiotics are very active against gram-positive bacteria and some gram-negative bacteria.[13] Their broad spectrum of activity can be attributed to their improved stability to many bacterial beta-lactamases compared to penicillins.[14]

Spectrum of activity

Gram-positive aerobes:[13][14]

- Staphylococcus aureus (including beta-lactamase producing strains)

- Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and other strains of streptococci

Gram-Negative Aerobes:

Non susceptible

The following are not susceptible:[13][14]

- Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus

- Enterococcus

- most strains of indole positive Proteus (Proteus vulgaris)

- Enterobacter spp.

- Morganella morganii

- Providencia rettgeri

- Serratia spp.

- Pseudomonas spp.

- Listeria

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 3 grams (by injection).[3]

Special populations

Pregnancy

Cefazolin is pregnancy category B, indicating general safety for use in pregnancy. Caution should be used in breastfeeding as a small amount of cefazolin enters the breast milk.[13] Cefazolin can be used prophylactically against perinatal Group B streptococcal infection (GBS). Although penicillin and ampicillin are the standard of care for GBS prophylaxis, penicillin-allergic women with no history of anaphylaxis can be given cefazolin instead. These patients should be closely monitored as there is a small chance of an allergic reaction due to the similar structure of the antibiotics.[16]

Newborns

There has been no established safety and effectiveness for use in premature infants and neonates.[13]

Elderly

No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed in clinical trials comparing elderly and younger subjects, however the trials could not eliminate the possibility that some older individuals may have a higher level of sensitivity.[13]

Additional considerations

People with kidney disease and those on hemodialysis may need the dose adjusted.[13] Cefazolin levels are not significantly affected by liver disease.

As with other antibiotics, cefazolin may interact with other medications being taken. Some important drugs that may interact with cefazolin such as probenecid.[14]

Side effects

Side effects associated with use of cefazolin therapy include:[13]

- Common (1-10%): diarrhea, stomach pain or upset stomach, vomiting, and rash.

- Uncommon (<1%): dizziness, headache, fatigue, itching, transient hepatitis.[17]

Patients with penicillin allergies could experience a potential reaction to cefazolin and other cephalosporins.[13] As with other antibiotics, patients experiencing watery and/or bloody stools occurring up to three months following therapy should contact their prescriber.[13]

Like those of several other cephalosporins, the chemical structure of cefazolin contains an N-methylthiodiazole (NMTD or 1-MTD) side-chain. As the antibiotic is broken down in the body, it releases free NMTD, which can cause hypoprothrombinemia (likely due to inhibition of the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase) and a reaction with ethanol similar to that produced by disulfiram (Antabuse), due to inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase.[18] Those with an allergy to penicillin may develop a cross sensitivity to cefazolin.[19][20]

Mechanism of action

Cefazolin inhibits cell wall biosynthesis by binding Penicillin binding proteins which stops peptidoglycan synthesis. Penicillin binding proteins are bacterial proteins that help to catalyze the last stages of peptidoglycan synthesis, which is needed to maintain the cell wall. They remove the D-alanine from the precursor of the peptidoglycan. The lack of synthesis causes the bacteria to lyse because they also continually break down their cell walls. Cefazolin is bactericidal, meaning it kills the bacteria rather than inhibiting their growth.[14]

Society and culture

Cost

Cefazolin is relatively inexpensive.[21]

Brand names

It was initially marketed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Ancef.[22]

Other trade names include: Cefacidal, Cefamezin, Cefrina, Elzogram, Faxilen, Gramaxin, Kefzol, Kefol, Kefzolan, Kezolin, Novaporin, Reflin, Zinol, and Zolicef.

References

- ↑ "Cefazolin". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Cefazolin Sodium". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Beauduy, Camille E.; Winston, Lisa G. (2020). "43. Beta-lactam and other cell wall - & membrane - active antibiotics". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 830–832. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 106. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 84. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 493. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ↑ US patent 3516997, Tadayoshi Takano, Masaru Kurita, Hiroo Nikaido, Masashi Mera, Nobukiyo Konishi, Ritsuko Nakagawa, "3,7-disubstituted cephalosporin compounds and preparation thereo", published 1970-06-23, issued 1970-06-23, assigned to Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co Ltd

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Single Drug Information | International Medical Products Price Guide". Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ↑ "5. Infection". British National Formulary (BNF) (82 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2021 – March 2022. pp. 558–559. ISBN 978-0-85711-413-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ Zanichelli, Veronica; Sharland, Michael; Cappello, Bernadette; Moja, Lorenzo; Getahun, Haileyesus; Pessoa-Silva, Carmem; Sati, Hatim; van Weezenbeek, Catharina; Balkhy, Hanan; Simão, Mariângela; Gandra, Sumanth; Huttner, Benedikt (1 April 2023). "The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 101 (4): 290–296. doi:10.2471/BLT.22.288614. ISSN 0042-9686. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "DailyMed - CEFAZOLIN - cefazolin sodium injection, powder, for solution". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Trevor, Anthony J.; Katzung, Bertram G.; Masters, Susan (2015). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill Education. pp. 776–778. ISBN 978-0-07-182505-4.

- ↑ "Cefazolin (Injection Route)". Mayo Clinic. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-15. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ↑ "Cefazolin Prescribing Information" (PDF). FDA. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Stork CM (2006). Antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 847.

- ↑ "Pharmaceutical Sciences CSU Parenteral Antibiotic Allergy cross-sensitivity chart" (PDF). Vancouver Acute Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vancouver Hospital & Health Sciences Centre. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ↑ Gonzalez-Estrada A, Radojicic C (May 2015). "Penicillin allergy: A practical guide for clinicians". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 82 (5): 295–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.82a.14111. PMID 25973877.

- ↑ Cunha, Burke A.; Cunha, Burke (2009). Infectious Diseases in Critical Care Medicine. CRC Press. p. 506. ISBN 978-1-4200-9241-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "Cefazolin Sodium Injection: MedlinePlus Drug Information". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- MedlinePlus Drug Information: Cefazolin Sodium Injection. Archived 2008-10-01 at the Wayback Machine