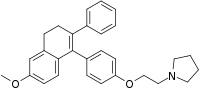

Nafoxidine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | U-11,000A; NSC-70735 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.222.756 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H31NO2 |

| Molar mass | 425.572 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Nafoxidine (INN; developmental code names U-11,000A) or nafoxidine hydrochloride (USAN) is a nonsteroidal selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) or partial antiestrogen of the triphenylethylene group that was developed for the treatment of advanced breast cancer by Upjohn in the 1970s but was never marketed.[1][2][3] It was developed at around the same time as tamoxifen and clomifene, which are also triphenylethylene derivatives.[2] The drug was originally synthesized by the fertility control program at Upjohn as a postcoital contraceptive, but was subsequently repurposed for the treatment of breast cancer.[4] Nafoxidine was assessed in clinical trials in the treatment of breast cancer and was found to be effective.[5][6] However, it produced side effects including ichthyosis, partial hair loss, and phototoxicity of the skin in almost all patients,[5] and this resulted in the discontinuation of its development.[4][7]

Nafoxidine is a long-acting estrogen receptor ligand, with a nuclear retention in the range of 24 to 48 hours or more.[8]

| Antiestrogen | Dosage | Year(s) | Response rate | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethamoxytriphetol | 500–4,500 mg/day | 1960 | 25% | Acute psychotic episodes |

| Clomifene | 100–300 mg/day | 1964–1974 | 34% | Fears of cataracts |

| Nafoxidine | 180–240 mg/day | 1976 | 31% | Cataracts, ichthyosis, photophobia |

| Tamoxifen | 20–40 mg/day | 1971–1973 | 31% | Transient thrombocytopeniaa |

| Footnotes: a = "The particular advantage of this drug is the low incidence of troublesome side effects (25)." "Side effects were usually trivial (26)." Sources: [9][10] | ||||

References

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 848–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 JORDAN V. CRAIG; B.J.A. Furr (5 February 2010). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1-59259-152-7.

- ↑ Georg F. Weber (22 July 2015). Molecular Therapies of Cancer. Springer. pp. 361–. ISBN 978-3-319-13278-5.

- 1 2 Hormones and Breast Cancer. Elsevier. 25 June 2013. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-12-416676-9.

- 1 2 Coelingh Bennink HJ, Verhoeven C, Dutman AE, Thijssen J (2017). "The use of high-dose estrogens for the treatment of breast cancer". Maturitas. 95: 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010. PMID 27889048.

- ↑ Steinbaum, Fred L.; de Jager, Robert L.; Krakoff, Irwin H. (1978). "Clinical trial of nafoxidine in advanced breast cancer". Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 4 (2): 123–126. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950040207. ISSN 0098-1532. PMID 661750.

- ↑ Aurel Lupulescu (24 October 1990). Hormones and Vitamins in Cancer Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-8493-5973-6.

- ↑ Wallach, Edward E.; Hammond, Charles B.; Maxson, Wayne S. (1982). "Current status of estrogen therapy for the menopause". Fertility and Sterility. 37 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)45970-4. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 6277697.

- ↑ Jensen EV, Jordan VC (June 2003). "The estrogen receptor: a model for molecular medicine". Clin. Cancer Res. 9 (6): 1980–9. PMID 12796359.

- ↑ Howell, Anthony; Jordan, V. Craig (2013). "Adjuvant Antihormone Therapy". In Craig, Jordan V. (ed.). Estrogen Action, Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators And Women's Health: Progress And Promise. World Scientific. pp. 229–254. doi:10.1142/9781848169586_0010. ISBN 978-1-84816-959-3.