eIF2

Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2) is an eukaryotic initiation factor. It is required for most forms of eukaryotic translation initiation. eIF2 mediates the binding of tRNAiMet to the ribosome in a GTP-dependent manner. eIF2 is a heterotrimer consisting of an alpha (also called subunit 1, EIF2S1), a beta (subunit 2, EIF2S2), and a gamma (subunit 3, EIF2S3) subunit.

Once the initiation phase has completed, eIF2 is released from the ribosome bound to GDP as an inactive binary complex. To participate in another round of translation initiation, this GDP must be exchanged for GTP.

Function

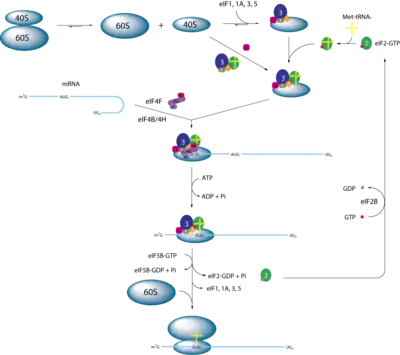

eIF2 is an essential factor for protein synthesis that forms a ternary complex (TC) with GTP and the initiator Met-tRNAiMet. After its formation, the TC binds the 40S ribosomal subunit to form the 43S preinitiation complex (43S PIC). 43S PIC assembly is believed to be stimulated by the initiation factors eIF1, eIF1A, and the eIF3 complex according to in vitro experiments. The 43S PIC then binds mRNA that has previously been unwound by the eIF4F complex. The 43S PIC and the eIF4F proteins form a new 48S complex on the mRNA, which starts searching along the mRNA for the start codon (AUG). Upon base pairing of the AUG-codon with the Met-tRNA, eIF5 (which is a GTPase-activating protein , or GAP) is recruited to the complex and induces eIF2 to hydrolyse its GTP. This causes eIF2-GDP to be released from this 48S complex and translation begins after recruitment of the 60S ribosomal subunit and formation of the 80S initiation complex. Finally, with the help of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) eIF2B,[1] the GDP in eIF2 is exchanged for a GTP and the ternary complex reforms for a new round of translation initiation. [2][3][4]

Structure

eIF2 is a heterotrimer of a total molar mass of 126 kDa that is composed of the three sub-units: α (sub-unit 1), β (sub-unit 2), and γ (sub-unit 3). The sequences of all three sub-units are highly conserved (pairwise amino acid identities for each sub-unit range from 47 to 72% when comparing the proteins of Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae).

| sub-unit | Alpha | Beta | Gamma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight / kDa | 36 | 38 | 52 |

| Similarity | eIF2-alpha family IPR011488 |

eIF2-beta / eIF5 family IPR002735 |

GTP-binding elongation factor family (and others) P41091 |

| Interactions | Binding of eIF5, eIF2B and RNA | Binding of GTP and RNA |

The α-subunit contains the main target for phosphorylation, a serine at position 51. It also contains a S1 motif domain, which is a potential RNA binding-site. Therefore, the α-subunit can be considered the regulatory subunit of the trimer.

The β-subunit contains multiple phosphorylation sites (residues 2, 13, 67, 218). What is important to consider is that there are also three lysine clusters in the N-terminal domain (NTD), which are important for the interaction with eIF2B. Moreover, the sequence of the protein comprises a zinc finger motif that was shown to play a role in both ternary complex and 43S preinitiation complex formation. There are also two guanine nucleotide-binding sequences that have not been shown to be involved in the regulation of eIF2 activity. The β-subunit is also believed to interact with both tRNA and mRNA.

The γ-subunit comprises three guanine nucleotide-binding sites and is known to be the main docking site for GTP/GDP. It also contains a tRNA-binding cavity that has been shown by X-ray crystallography. A zinc knuckle motif is able to bind one Zn2+ cation.[4][6][7] It is related to some elongation factors like EF-Tu.[8]

Regulation

eIF2 activity is regulated by a mechanism involving both guanine nucleotide exchange and phosphorylation. Phosphorylation takes place at the α-subunit, which is a target for a number of serine kinases that phosphorylate serine 51. Those kinases act as a result of stress such as amino acid deprivation (GCN2), ER stress (PERK), the presence of dsRNA (PKR) heme deficiency (HRI), or interferon.[10] Once phosphorylated, eIF2 shows increased affinity for eIF2B, its GEF. However, eIF2B is able to exchange GDP for GTP only if eIF2 is in its unphosphorylated state. Phosphorylated eIF2, however, due to its stronger binding, acts as an inhibitor of its own GEF (eIF2B). Since the cellular concentration of eIF2B is much lower than that of eIF2, even a small amount of phosphorylated eIF2 can completely abolish eIF2B activity by sequestration. Without the GEF, eIF2 can no longer be returned to its active (GTP-bound) state. As a consequence, translation comes to a halt since initiation is no longer possible without any available ternary complex. Furthermore, low concentration of ternary complex allows the expression of GCN4 (starved condition), which, in turn, results in increased activation of amino acid synthesis genes[2][3][4][9][11]

Disease

Since eIF2 is essential for most forms of translation initiation and therefore protein synthesis, defects in eIF2 are often lethal. The protein is highly conserved among evolutionary remote species - indicating a large impact of mutations on cell viability. Therefore, no diseases directly related to mutations in eIF2 can be observed. However, there are many illnesses caused by down-regulation of eIF2 through its upstream kinases. For example, increased concentrations of active PKR and inactive (phosphorylated) eIF2 were found in patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease. There is also one proven example of a disease related to the GEF eIF2B. Mutations in all of the five subunits of eIF2B are associated with Vanishing White Matter (VWM) disease, a genetic leukodystrophy which causes the brain's white matter to degenerate and disappear.[12][13] It is still not fully understood why only brain cells seem to be affected by these defects. Potentially reduced levels of unstable regulatory proteins might play a role in the development of the diseases mentioned.[4][14]

See also

References

- eIF2B consists of the sub-units EIF2B1, EIF2B2, EIF2B3, EIF2B4, EIF2B5

- Kimball SR (1999). "Eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31 (1): 25–9. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00128-9. PMID 10216940.

- Hershey JW (1989). "Protein phosphorylation controls translation rates" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 264 (35): 20823–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)30005-5. PMID 2687263.

- Hinnebusch AG (2005). "Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59: 407–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. PMID 16153175.

- Kimball SR, Jefferson LS (2004). "Amino acids as regulators of gene expression". Nutr. Metab. 1 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-1-3. PMC 524028. PMID 15507151.

- Roll-Mecak A, Alone P, Cao C, Dever TE, Burley SK (2004). "X-ray structure of translation initiation factor eIF2gamma: implications for tRNA and eIF2alpha binding". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (11): 10634–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.M310418200. PMID 14688270.

- Ito T, Marintchev A, Wagner G (2004). "Solution structure of human initiation factor eIF2alpha reveals homology to the elongation factor eEF1B". Structure. 12 (9): 1693–704. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.07.010. PMID 15341733.

- Schmitt, E; Blanquet, S; Mechulam, Y (2 April 2002). "The large subunit of initiation factor aIF2 is a close structural homologue of elongation factors". The EMBO Journal. 21 (7): 1821–32. doi:10.1093/emboj/21.7.1821. PMC 125960. PMID 11927566.

- Nika J, Rippel S, Hannig EM (2001). "Biochemical analysis of the eIF2beta gamma complex reveals a structural function for eIF2alpha in catalyzed nucleotide exchange". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2): 1051–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007398200. PMID 11042214.

- Samuel CE (1979). "Mechanism of interferon action: Phosphorylation of protein synthesis initiation factor eIF-2 in interferon-treated human cells by a ribosome-associated kinase processing site specificity similar to hemin-regulated rabbit reticulocyte kinase". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 76 (2): 600–4. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76..600S. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.2.600. PMC 382996. PMID 284384.

- Hope A, Struhl K (1987). "GCN4, a eukaryotic transcriptional activator protein, binds as a dimer to target DNA". The EMBO Journal. 6 (9): 2781–2784. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02573.x. PMC 553703. PMID 3678204.

- Knaap, Marjo S. van der; Pronk, Jan C.; Scheper, Gert C. (2006-05-01). "Vanishing white matter disease". The Lancet Neurology. 5 (5): 413–423. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70440-9. ISSN 1474-4422. PMID 16632312. S2CID 44301370.

- Leegwater, Peter A. J.; Vermeulen, Gerre; Könst, Andrea A. M.; Naidu, Sakkubai; Mulders, Joyce; Visser, Allerdien; Kersbergen, Paula; Mobach, Dragosh; Fonds, Dafna; van Berkel, Carola G. M.; Lemmers, Richard J. L. F. (December 2001). "Subunits of the translation initiation factor eIF2B are mutant in leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter". Nature Genetics. 29 (4): 383–388. doi:10.1038/ng764. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 11704758. S2CID 20313523.

- Chang RC, Yu MS, Lai CS (2006). "Significance of molecular signaling for protein translation control in neurodegenerative diseases". Neurosignals. 15 (5): 249–58. doi:10.1159/000102599. PMID 17496426.

External links

- EIF-2 at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Cap-dependent translation initiation from Nature Reviews Microbiology. A good image and overview of the function of initiation factors