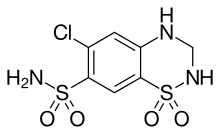

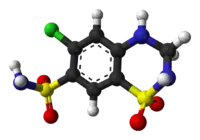

Hydrochlorothiazide

Hydrochlorothiazide is a diuretic medication often used to treat high blood pressure and swelling due to fluid build up.[3] Other uses include treating diabetes insipidus and renal tubular acidosis and to decrease the risk of kidney stones in those with a high calcium level in the urine.[3] Hydrochlorothiazide is less effective than chlortalidone for prevention of heart attack or stroke.[4][3][5] Hydrochlorothiazide is taken by mouth and may be combined with other blood pressure medications as a single pill to increase effectiveness.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Apo-hydro, others |

| Other names | HCTZ, HCT |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682571 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (capsules, tablets, oral solution) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable (~70% on average) |

| Metabolism | Not significant[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 5.6–14.8 h |

| Excretion | Primarily kidney (>95% as unchanged drug) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.367 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H8ClN3O4S2 |

| Molar mass | 297.73 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Potential side effects include poor kidney function; electrolyte imbalances, including low blood potassium, and, less commonly, low blood sodium, gout, high blood sugar, and feeling lightheaded with standing.[3] While allergies to hydrochlorothiazide are reported to occur more often in those with allergies to sulfa drugs, this association is not well supported.[3] It may be used during pregnancy, but it is not a first-line medication in this group.[3]

It is in the thiazide medication class and acts by decreasing the kidneys' ability to retain water.[3] This initially reduces blood volume, decreasing blood return to the heart and thus cardiac output.[6] It is believed to lower peripheral vascular resistance in the long run.[6]

Two companies, Merck and Ciba, state they discovered the medication which became commercially available in 1959.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] It is available as a generic drug[3] and is relatively affordable.[9] In 2020, it was the eleventh most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 41 million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

Hydrochlorothiazide is used for the treatment of hypertension, congestive heart failure, symptomatic edema, diabetes insipidus, renal tubular acidosis.[3] It is also used for the prevention of kidney stones in those who have high levels of calcium in their urine.[3]

Multiple studies suggest hydrochlorothiazide could be used as initial monotherapy in people with primary hypertension; however, the decision should be weighed against the consequence of long-term adverse metabolic abnormalities.[12][13][14] A review of randomised trials showed varying efficacy in cardiovascular outcomes on age, ethnicity and existing cardiovascular risks.[14][15] A systematic, multinational, large-scale analysis by Suchard et al. supported equivalence between drug classes for initiating monotherapy in hypertension, however thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics showed better primary effectiveness and safety profiles than angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.[12]

Hydrochlorothiazide is less potent but not necessarily less effective than chlorthalidone in reducing blood pressure.[16][17] More robust studies are required to confirm which drug is superior in reducing cardiovascular events.[18] Side effect profile for both drugs appear similar and are dose dependant.[16][17][18]

Hydrochlorothiazide is also sometimes used to prevent osteopenia and for treatment of hypoparathyroidism,[19] hypercalciuria, Dent's disease, and Ménière's disease. For diabetes insipidus, the effect of thiazide diuretics is presumably mediated by a hypovolemia-induced increase in proximal sodium and water reabsorption, thereby diminishing water delivery to the ADH-sensitive sites in the collecting tubules and increasing the urine osmolality.

A low level of evidence, predominantly from observational studies, suggests that thiazide diuretics have a modest beneficial effect on bone mineral density and are associated with a decreased fracture risk when compared with people not taking thiazides.[20][21][22] Thiazides decrease mineral bone loss by promoting calcium retention in the kidney, and by directly stimulating osteoblast differentiation and bone mineral formation.[23]

The combination of fixed-dose preparation such as losartan/hydrochlorothiazide has added advantages of a more potent antihypertensive effect with additional antihypertensive efficacy at the dose of 100 mg/25 mg when compared to monotherapy.[24][25]

Adverse effects

- Hypokalemia, or low blood levels of potassium are an occasional side effect. It can be usually prevented by potassium supplements or by combining hydrochlorothiazide with a potassium-sparing diuretic

- Other disturbances in the levels of serum electrolytes, including hypomagnesemia (low magnesium), hyponatremia (low sodium), and hypercalcemia (high calcium)

- Hyperuricemia (high levels of uric acid in the blood). All thiazide diuretics including hydrochlorothiazide can inhibit excretion of uric acid by the kidneys, thereby increasing serum concentrations of uric acid.This may increase the incidence of gout in doses of ≥ 25 mg per day and in more susceptible patients such as male gender of <60 years old.[26][27][28]

- Hyperglycemia, high blood sugar

- Hyperlipidemia, high cholesterol and triglycerides

- Headache

- Nausea/vomiting

- Photosensitivity

- Weight gain

- Pancreatitis

Package inserts contain vague and inconsistent data surrounding the use of thiazide diuretics in patients with allergies to sulfa drugs, with little evidence to support these statements.[29] A retrospective cohort study conducted by Strom et al. concluded that there is an increased risk of an allergic reaction occurring in patients with a predisposition to allergic reactions in general rather than cross reactivity from structural components of the sulfonamide-based drug.[30] Prescribers should examine the evidence carefully and assess each patient individually, paying particular attention to their prior history of sulfonamide hypersensitivity rather than relying on drug monograph information.[31]

There is an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer.[32] In August 2020, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration required the Product Information (PI) and Consumer Medicine Information (CMI) for medicines containing hydrochlorothiazide to be updated to include details about an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer.[33] In August 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated the drug label about an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer (basal cell skin cancer or squamous cell skin cancer).[34]

Mechanism of action

Hydrochlorothiazide belongs to the thiazide class of diuretics. It reduces blood volume by acting on the kidneys to reduce sodium (Na+) reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule. The major site of action in the nephron appears on an electroneutral NaCl co-transporter by competing for the chloride site on the transporter. By impairing Na+ transport in the distal convoluted tubule, hydrochlorothiazide induces a natriuresis and concomitant water loss. Thiazides increase the reabsorption of calcium in this segment in a manner unrelated to sodium transport.[35] Additionally, by other mechanisms, hydrochlorothiazide is believed to lower peripheral vascular resistance.[6]

Dosage

In a double-blind, randomized study, the effects of 25 mg/day vs. 50 mg/day of hydrochlorothiazide were evaluated in geriatric patients (n = 51) with isolated systolic hypertension. Both dosages were associated with similar reductions in blood pressure; however, the higher dose (50 mg/day) caused a greater decline in serum potassium concentration.[36]

Society and culture

%252C_Singapore_-_20150210.jpg.webp)

Brand names

Hydrochlorothiazide is available as a generic drug under a large number of brand names, including Apo-Hydro, Aquazide, BPZide, Dichlotride, Esidrex, Hydrochlorot, Hydrodiuril, HydroSaluric, Hypothiazid, Microzide, Oretic and many others.

To reduce pill burden and in order to reduce side effects, hydrochlorothiazide is often used in fixed-dose combinations with many other classes of antihypertensive drugs such as:

- ACE inhibitors — e.g. Prinzide or Zestoretic (with lisinopril), Co-Renitec (with enalapril), Capozide (with captopril), Accuretic (with quinapril), Monopril HCT (with fosinopril), Lotensin HCT (with benazepril), etc.

- Angiotensin receptor blockers — e.g. Hyzaar (with losartan), Co-Diovan or Diovan HCT (with valsartan), Teveten Plus (with eprosartan), Avalide or CoAprovel (with irbesartan), Atacand HCT or Atacand Plus (with candesartan), etc.

- Beta blockers — e.g. Ziac or Lodoz (with bisoprolol),[37] Nebilet Plus or Nebilet HCT (with nebivolol), Dutoprol or Lopressor HCT (with metoprolol), etc.

- Direct renin inhibitors — e.g. Co-Rasilez or Tekturna HCT (with aliskiren)

- Potassium sparing diuretics: Dyazide and Maxzide triamterene[38]

Sport

Use of hydrochlorothiazide is prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency for its ability to mask the use of performance-enhancing drugs.[39]

References

- "Hydrochlorothiazide Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 30 July 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Beermann B, Groschinsky-Grind M, Rosén A (1976). "Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of hydrochlorothiazide". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 19 (5 (Pt 1)): 531–37. doi:10.1002/cpt1976195part1531. PMID 1277708. S2CID 22159706.

- "Hydrochlorothiazide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Roush GC, Messerli FH (January 2021). "Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide: major cardiovascular events, blood pressure, left ventricular mass, and adverse effects". Journal of Hypertension. 39 (6): 1254–1260. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002771. PMID 33470735. S2CID 231649367.

- Wright JM, Musini VM, Gill R (April 2018). "First-line drugs for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3. PMC 6513559. PMID 29667175.

- Duarte JD, Cooper-DeHoff RM (June 2010). "Mechanisms for blood pressure lowering and metabolic effects of thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics". Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 8 (6): 793–802. doi:10.1586/erc.10.27. PMC 2904515. PMID 20528637. NIHMSID: NIHMS215063.

- Ravina E (2011). The evolution of drug discovery: from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1st ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 74. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "Best drugs to treat high blood pressure The least expensive medications may be the best for many people". November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "Hydrochlorothiazide - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Suchard MA, Schuemie MJ, Krumholz HM, You SC, Chen R, Pratt N, et al. (November 2019). "Comprehensive comparative effectiveness and safety of first-line antihypertensive drug classes: a systematic, multinational, large-scale analysis". Lancet. 394 (10211): 1816–1826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32317-7. PMC 6924620. PMID 31668726.

- Musini VM, Gueyffier F, Puil L, Salzwedel DM, Wright JM, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (August 2017). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (8): CD008276. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008276.pub2. PMC 6483466. PMID 28813123.

- The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in High-Risk Hypertensive Patients Randomized to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor or Calcium Channel Blocker vs Diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

- Wing L, Reid C, Ryan P, Beilin L, Brown M, Jennings G et al. A Comparison of Outcomes with Angiotensin-Converting–Enzyme Inhibitors and Diuretics for Hypertension in the Elderly. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(7):583-592

- Ernst ME, Carter BL, Goerdt CJ, Steffensmeier JJG, Phillips BB, Zimmerman MB, et al. Comparative Antihypertensive Effects of Hydrochlorothiazide and Chlorthalidone on Ambulatory and Office Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):352-8.

- Peterzan MA, Hardy R, Chaturvedi N, Hughes AD. Meta-analysis of dose-response relationships for hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and bendroflumethiazide on blood pressure, serum potassium, and urate. Hypertension. 2012 Jun;59(6):1104-9.

- Dorsch MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, Bleske BE, Weder AB. Chlorthalidone Reduces Cardiovascular Events Compared With Hydrochlorothiazide: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57(4):689-94.

- Mitchell DM, Regan S, Cooley MR, Lauter KB, Vrla MC, Becker CB, Burnett-Bowie SA, Mannstadt M (December 2012). "Long-term follow-up of patients with hypoparathyroidism". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 (12): 4507–14. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1808. PMC 3513540. PMID 23043192.

- Aung K, Htay T, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (October 2011). "Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD005185. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005185.pub2. PMID 21975748.

- Xiao X, Xu Y, Wu Q (July 2018). "Thiazide diuretic usage and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of cohort studies". Osteoporosis International. 29 (7): 1515–1524. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4486-9. PMID 29574519. S2CID 4322516.

- Solomon DH, Ruppert K, Zhao Z, Lian YJ, Kuo IH, Greendale GA, Finkelstein JS (March 2016). "Bone mineral density changes among women initiating blood pressure lowering drugs: a SWAN cohort study". Osteoporosis International. 27 (3): 1181–1189. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3332-6. PMC 4813302. PMID 26449354.

- Dvorak MM, De Joussineau C, Carter DH, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA, Gamba G, et al. (September 2007). "Thiazide diuretics directly induce osteoblast differentiation and mineralized nodule formation by interacting with a sodium chloride co-transporter in bone". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 18 (9): 2509–16. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007030348. PMC 2216427. PMID 17656470.

- Lacourcière, Y (December 2003). "Antihypertensive effects of two fixed-dose combinations of losartan and hydrochlorothiazide versus hydrochlorothiazide monotherapy in subjects with ambulatory systolic hypertension". American Journal of Hypertension. 16 (12): 1036–1042. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.07.014. ISSN 0895-7061. PMID 14643578. S2CID 26447230.

- Musini, Vijaya M; Nazer, Mark; Bassett, Ken; Wright, James M (29 May 2014). "Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003824. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003824.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 24869750.

- Musini VM, Nazer M, Bassett K, Wright JM, et al. (Cochrane Hypertension Group) (May 2014). "Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003824. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003824.pub2. PMID 24869750.

- Hueskes BA, Roovers EA, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Janssens HJ, van de Lisdonk EH, Janssen M (June 2012). "Use of diuretics and the risk of gouty arthritis: a systematic review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 41 (6): 879–89. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.11.008. PMID 22221907.

- Wilson L, Nair KV, Saseen JJ (December 2014). "Comparison of new-onset gout in adults prescribed chlorthalidone vs. hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 16 (12): 864–8. doi:10.1111/jch.12413. PMC 8031516. PMID 25258088.

- Johnson KK, Green DL, Rife JP, Limon L (February 2005). "Sulfonamide cross-reactivity: fact or fiction?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 39 (2): 290–301. doi:10.1345/aph.1E350. PMID 15644481. S2CID 10642527.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, Margolis DJ, Lautenbach E, Hennessy S, et al. (October 2003). "Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (17): 1628–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022963. PMID 14573734.

- Ghimire S, Kyung E, Lee JH, Kim JW, Kang W, Kim E (June 2013). "An evidence-based approach for providing cautionary recommendations to sulfonamide-allergic patients and determining cross-reactivity among sulfonamide-containing medications". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 38 (3): 196–202. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12048. PMID 23489131.

- Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SA, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Pottegård A (April 2018). "Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: A nationwide case-control study from Denmark". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78 (4): 673–681.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042. PMID 29217346.

- "Hydrochlorothiazide". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 24 August 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "FDA approves label changes to hydrochlorothiazide". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Uniformed Services University Pharmacology Note Set #3 2010, Lectures #39 & #40, Eric Marks

- "Hydrochlorothiazide - Drug Summary". Prescribers' Digital Reference. 1973.

- "List of nationally authorised medicinal products : Active substance: bisoprolol / hydrochlorothiazide Procedure no.: PSUSA/00000420/202111" (PDF). Ema.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- "Triamterene and Hydrochlorothiazide". MedlinePlus. 1 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. January 2018.

External links

- "Hydrochlorothiazide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.