Chlortetracycline

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Aureomycin |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tetracycline[2] |

| Main uses | Conjunctivitis, including trachoma[3] |

| Side effects | Tooth staining, sun sensitivity, nausea, diarrhea[4] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Routes of use | By mouth, IV, topical |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 30% |

| Protein binding | 50 to 55% |

| Metabolism | Gastrointestinal tract, liver (75%) |

| Metabolites | Isochlortetracycline |

| Elimination half-life | 5.6 to 9 hours |

| Excretion | 60% kidney and >10% biliary |

| Chemical and physical data | |

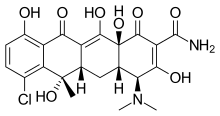

| Formula | C22H23ClN2O8 |

| Molar mass | 478.882 g·mol−1 |

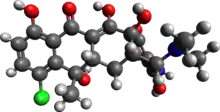

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | [α]D25−275°·cm3·dm−1·g−1 (methane) |

| Melting point | 168 to 169 °C (334 to 336 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 0.5–0.6 mg/mL (20 °C) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Chlortetracycline, sold under the brand name Aureomycin among others, is an antibiotic used to treat conjunctivitis, including trachoma.[3] It is generally used as an eye drop.[5] It may also be used for Rickettsiae.[4]

Side effects may include tooth staining, sun sensitivity, nausea, and diarrhea.[4] Other side effects may include kidney and liver problems.[4] Use is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[4] It is a tetracycline and works by interfering with protein production.[2]

Chlortetracycline was discovered in 1945 by Benjamin Minge Duggar and came into medical use in 1948.[6][7] The eye drop was approved in the United States in 1950; though is no longer commercially available.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to tetracycline.[8] It is also used in veterinary medicine.[9]

Medical uses

A combination cream with triamcinolone acetonide is available for the treatment of infected allergic dermatitis in humans.[10]

In veterinary medicine, chlortetracycline is commonly used to treat conjunctivitis in cats,[11] dogs and horses. It is also used to treat infected wounds in cattle, sheep and pigs, and respiratory tract infections in calves, pigs and chickens.[10]

Contraindications

Chlortetracycline for systemic use is contraindicated in animals with severe hepatic or renal impairment. Topical chlortetracycline must not be used on the udder of animals whose milk is intended for human consumption.[10]

Side effects

Like other tetracyclines, chlortetracyclin can inhibit bone and tooth mineralization in growing and unborn animals, and color their teeth yellow or brown. It can also impair liver and kidney function. Allergic reactions are rare.[10]

Interactions

Chlortetracycline may increase the anticoagulant activities of acenocoumarol. The risk or severity of adverse effects can be increased when chlortetracycline is combined with acitretin, adapalene, or alitretinoin. Aluminum phosphate and aluminum hydroxide can cause decreases in the absorption of chlortetracycline resulting in a reduced serum concentration and potentially a decrease in efficacy. The therapeutic efficacy of mecillinam (amdinocillin), amoxicillin, and ampicillin can be decreased when used in combination with chlortetracycline. Chlortetracycline may increase the neuromuscular blocking activities of atracurium besilate.[12]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

History

Chlortetracycline was discovered in 1945 at Lederle Laboratories under the supervision of scientist Yellapragada Subbarow, Benjamin Minge Duggar. They were helped by Louis T. Wright,[13] a surgeon who conducted this medications first human experiments. Duggar identified the antibiotic as the product of an actinomycete he cultured from a soil sample collected from Sanborn Field at the University of Missouri.[14]

References

- ↑ "chlortetracycline | C22H23ClN2O8 - PubChem". Pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- 1 2 Sneader, Walter (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- 1 2 "eEML - Electronic Essential Medicines List". list.essentialmeds.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scholar, Eric (2007). "Chlortetracycline". xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference: 1–5. doi:10.1016/B978-008055232-3.61451-5.

- 1 2 "Chlortetracycline: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ Ravina, Enrique (18 April 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 279. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ Riviere, Jim E.; Papich, Mark G. (17 March 2009). Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 902. ISBN 978-0-8138-2061-3. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Click to open content tools § 558.128 Chlortetracycline". Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Austria-Codex (in Deutsch). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. 2018.

- ↑ Merck Veterinary Manual. Merckvetmanual.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ↑ "Chlortetracycline - DrugBank". Drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 2016-10-27. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ↑ Posner, Gerald. PHARMA : Greed, Lies, and the Poisoning of America. S.L., Avid Reader Pr, 2021, pp. 47–57.

- ↑ Jukes TH (1985). "Some historical notes on chlortetracycline". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 7 (5): 702–7. doi:10.1093/clinids/7.5.702. PMID 3903946.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|